For white collar workers who have made an easy transition to working from home, the prospect of a four-day work week, as proposed by India’s new labour codes, created some excitement recently. But for the bulk of India’s workforce working in the informal sector – and for many skilled workers too – the new proposal will mean little or even, potentially, worse conditions.

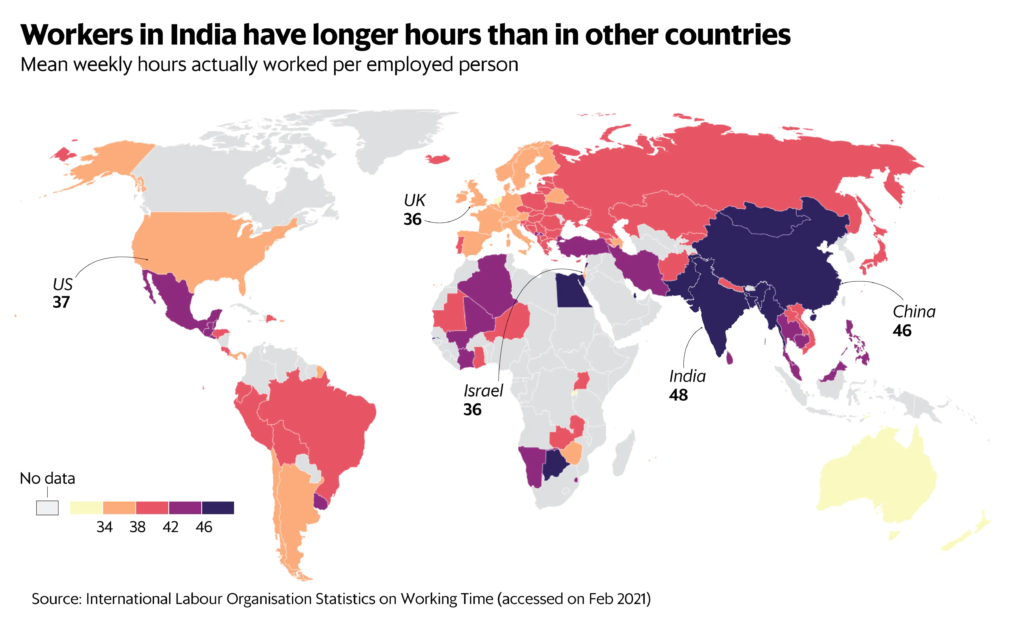

Indians are already among the most overworked workers globally. Gambia, Mongolia, Maldives, and Qatar are the only countries where an average worker works longer than an Indian worker, data from the International Labour Organization (ILO) shows. With a 48-hour working week, India ranks fifth among all countries for which ILO estimates actual mean working hours. The estimates are derived from household surveys conducted by national agencies. For most countries, the data refers to 2019 but for a few, it pertains to previous years.

Chart: Gross Monthly Minimum Wage Levels of Countries, 2019, PPP values

Despite their long hours, Indian workers are not making much money. India had the lowest statutory minimum wage of any country in the Asia Pacific region, except for Bangladesh as of 2019. India’s minimum wages are among the lowest in the world, except for some sub-Saharan African nations, according to the 2020-21 ILO Global Wage Report. Actual wage levels can differ from the statutory minimum wages across countries but the two tend to be closely linked, especially for blue collar workers.

Within India, it is the better-paid workers in cities who tend to work longer than their rural counterparts, data from the 2018-19 Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) shows. Men work longer hours than women in both rural and urban areas, and for both men and women, the hours of work are longer in urban areas.

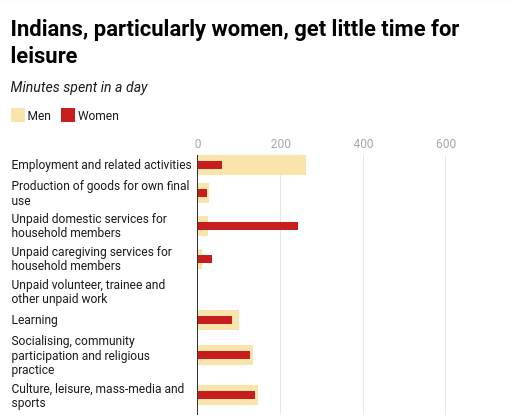

In 2019, India conducted its first time-use survey in two decades. That survey also finds similar trends. Men spent over four times as much time in their day on paid work as women, and urban men spent over an hour more than their male counterparts on paid work each day.

By India’s definition of hours worked, time spent on actual work, on travel between work locations, and on short bathroom or tea breaks is included, while time spent commuting to work and on longer meal breaks is not included. Since the data is derived from household surveys, it includes both formal and informal employment of all types.

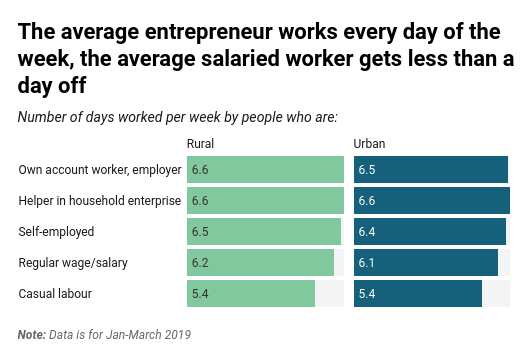

But far from a four-day week, most Indian workers work nearly every day at the moment. Those who work for themselves work virtually every day. Even salaried employees work more than six days a week on average.

Labour secretary Apurva Chandra has said that some employers might want to give their employees a five or four-day week. Companies that choose a four-day week will have to provide three consecutive days of holiday, while potentially being allowed to institute 12-hour shifts for the four working days. The four labour codes were passed by Parliament in September 2020. The ministry of labour and employment brought out the first draft of the rules in December 2020 and received comments in January. The labour minister has said that they are considering the responses and working on the next draft. Representatives of labour unions have been pushing back against any increase in the weekly hours of work over 48 hours, but Chandra reiterated that the 48 hours limit would not change.

The new proposal for a four-day week will mean very little to most of India’s workforce as fixed hours apply only to the formal workforce, said Ashwini Deshpande, professor of economics at Ashoka University. Within the formal workforce, 12-hour work days, even if in work-from-home mode, could prove difficult for women who bear the bulk of the burden of unpaid domestic work and childcare, Deshpande said. Her research has shown that the gender gap in housework in India has not only returned to pre-pandemic levels, the gap has actually widened further. “That said, there is an important conversation around leisure, and work-life balance that needs to take place in India,” she said.

Data from the official time-use survey shows that Indians spend less than a tenth of their day on leisure activities, with women getting even less time than men to spend on leisure.

With seven out of ten workers in the non-farm sector in informal employment, seven out of ten salaried workers in jobs with no written contract, and over half in jobs that gave them no paid leave or social security benefits, changes to India’s new labour codes will at best provide some degree of flexibility to a small sliver of India’s overworked, underpaid workforce.

(Rukmini S. is a Chennai-based journalist. Article courtesy: Mint, an Indian newsportal.)