Derailed Priorities: Has the Investments in Our Safety in the Indian Railways Been Compromised?

Financial Accountability Network

This week, the Sealdah-bound Kanchanjunga Express met with a disaster when a goods train crashed into it near Rangapani station in West Bengal. The violent collision led to the derailment of three rear compartments, leaving at least eight people dead and around 30 injured. Under the watch of Railway Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw, this is the second time within a span of one year that a catastrophic train accident has claimed lives, leaving many more injured.

We, of course, remember the Balasore accident on June 2, 2023, where a catastrophic three-train collision snatched away at least 291 lives and wounded over 1,000 more. The accident involved the Bengaluru-Howrah Superfast Express, the Shalimar-Chennai Central Coromandel Express, and a stationary goods train. The initial impact of the Coromandel Express with the goods train, followed by the Yashwantpur-Howrah Express slamming into derailed coaches, exposed egregious failures in railway operations and safety protocols. Investigations after the accident revealed that an undetected fault in the wiring of a location box near Bahanaga Bazaar Railway Station had lingered for five years. The Commission of Rail Safety (CRS) report laid the blame squarely on the S&T Department and let the government slide through the cracks once again.

But if we look deeper, the government in such accidents is more culpable than meets the eye. There is an urgent need to address 10,000 kilometers of tracks requiring immediate attention, along with the annual renewal of 4,500 kilometers of tracks. The Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) found a staggering shortfall of Rs 103,395 crore needed for track renewal. By the end of the fiscal year 2020-21, the railway system needed to replace aging assets worth Rs 94,873 crore from the Depreciation Reserve Fund. Specifically, around 60% of these funds, or Rs 58,459 crore, were designated for the renewal of railway tracks. However, the CAG report revealed that only a paltry Rs 671.92 crore, or 0.7% of the allocated funds, was actually utilized for this critical purpose. In December 2022, a report by the CAG revealed a disturbing misuse of funds allocated for railway safety in India. The Rashtriya Rail Sanraksha Kosh (RRSK) – a special fund created by the Narendra Modi government in 2017 to enhance railway safety – had its resources diverted to trivial expenses such as foot massagers, crockery, and furniture. Alarmingly, only a minuscule portion of the funds earmarked for track renewal was used as intended.

In the aftermath of the Kanchanjunga Express calamity, the government has offered compensation of 10 lakh for the families of the deceased, 2.5 lakh for the seriously injured, and 50,000 for those with minor injuries. But such promises do nothing in terms of the structural concerns that are behind the neglect of priorities in the Railways. Such ex-post compensation, while necessary, when considered along with the conscious neglect of safety and reliability related investments (especially in signaling and in track modernisation) implies that the railways have been trading lives for money “saved”, which is entirely unethical.

The government’s fixation on flashy projects like the Vande Bharat Express seem to be eating into fundamental safety concerns. Similarly, Local passenger trains are gradually being replaced by express trains like VandeBharat, equipped with amenities such as air conditioning and Wi-Fi. The needs of the majority of passengers, particularly those traveling in passenger and unreserved compartment trains who cannot afford the high tariffs of these trains, have been increasingly ignored. When we look at the frequent videos these days of people being forced to travel like livestock stacked inside the train toilets and vestibules, we should yet again remind ourselves that it is the outcome of conscious decisions of the government. Between 2012 and 2022 the seats/berths in the General section came down from 50% to 43%. Even Non AC Sleeper sections seats/berths have come down from 36% to 33%. While AC coaches have increased significantly from 15% to 24%! Railways are replacing affordable sleeper coaches with more expensive AC counterparts on faster trains that cost over twice as much as the original second-class tickets.

Moreover, attempting to run a few trains at high speed only reduces the carrying capacity further. India has the highest train varieties (in terms of speed) which reduces the capacity of the tracks. By moving towards a standard speed and acceleration that all passenger trains (mail, express, “super-fast”, passenger) achieve, the congestion on the railways can greatly reduce, allowing the rail to run high value low cost trains for all.

The Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) observed a decrease in the punctuality of mail and express trains, dropping from 79% in 2012-’13 to 69.23% in 2018-’19. In a recent report by the Times of India, it was highlighted that the average speed of passenger trains in India has decreased by over 5 km per hour compared to the previous year. Similarly, for freight trains, there has been a decline in average speed by nearly 6 km per hour. These significant developments get shrouded by the fanfare around selfie booths with the PM. As per response to an RTI, it has come to the fore that, in the Central Railway Zone, these selfie booths in railway stations have been set up on platforms, costing Rs 6.25 lakhs each.

The luxurious Vande Bharat trains come at a premium cost. While a standard second-class sleeper ticket on an express train between Delhi and Kanpur costs only Rs 300, the cheapest Vande Bharat fare is a staggering Rs 1,115. Express trains have been rebranded as “superfast”. While there has been hardly any increase in effective speed, ticket prices have soared for the common people.These recent disasters have laid bare the truth that in the name of advances in technology and infrastructure, the fundamental safety of railway operations and affordability is being compromised.

Post the Balasore accident, the government had announced plans to implement the Kavach safety system on 6,000 km of tracks by 2023 on the Delhi – Guwahati route which would have covered Bengal too, but it has only been deployed on 1,500 km. If Kavach had been in place, the Kanchanjunga accident could have been avoided.

In light of these tragedies, we have some key demands to ensure a fair and transparent investigation.

- To ensure a fair and transparent investigation, it is essential to examine not only this accident but also the series of accidents in recent times. This investigation should aim to identify the systemic reasons for the severe compromise of rail safety and hold those responsible accountable.

- The findings and proposed safety measures must be presented to the parliament, along with a detailed timeline for the implementation of each measure. Furthermore, progress reports on the completion and compliance of these safety measures should be regularly submitted to the parliament and made available to the public to ensure accountability and transparency.

Our view is that our entire railway network is vulnerable, particularly in Eastern and Northeastern States. It is imperative that stringent measures be taken to secure the safety of our railway tracks to prevent future catastrophes. It is the ordinary citizens who suffer the consequences of systemic negligence.

As per government’s own data presented in parliament, we have witnessed 71 accidents per annum since 2014. Accountability must be demanded for the millions of lives that rely on the railway network every single day. The blood spilled on these tracks cries out for justice and reform before more innocent lives are lost to the wheels of neglect and incompetence. Is this the true meaning of Modi’s guarantee?

(Financial Accountability Network India is a collective of civil society organisations, unions, people’s movements and concerned citizens to raise the issues of accountability and transparency of the national financial institutions. It also looks critically at the economic and financial policies that have an impact on the people.)

Why the Indian Railways Changed Course – and How It Can Get Back on Track

Kalyan Sundareswaran & G Sriram Iyer

Crowds and enormous numbers have always been an essential part of the Indian Railways. As the fourth-largest network in the world, it transports nearly 23 million passengers every day on its 68,000 km of track. Put another way, in 2020, it operated 1.1 trillion km of passenger traffic.

But over the past few months, images that have surfaced on social media show passengers across classes crammed into trains at levels that seem inhuman.

The contrast is especially stark because other influential corners of social media are consistently propagating images of plush, roomy trains being flagged off by the score. When the Railways itself repeatedly refuses to acknowledge the problem or, worse still, outright denies it – for example, the X handle of the railways ministry in April refuted videos of overcrowding on a train as “misleading” – the dehumanisation seems complete.

Several recent decisions by Indian Railways seem to have been made to increase revenues in the passenger segment while perpetuating the illusion of development and an emulation of the first world.

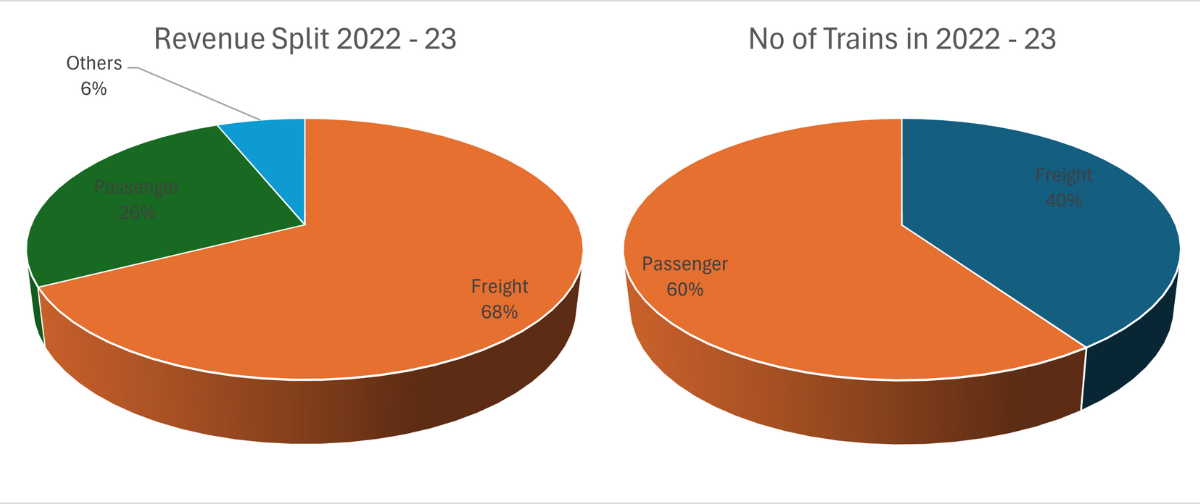

However, it is worth noting that the passenger segment was never profitable and was always subsidised by freight earnings.

The mission statement of the Indian Railways does not make any reference to revenue generation either and only focuses on passenger safety and basic rights. However, after the Covid-19 lockdown, the Railways gradually discontinued the low-cost passenger trains used almost entirely by working-class Indians. They rebranded them as “express specials” and charged express category fares that were 50%-100% higher.

Earlier this year, however, in the face of protests and some media attention, they were forced to restore the second-class ordinary fares.

Apart from this, several other revenue-enhancing measures have been undertaken such as introducing airline-like surge pricing across key trains increasing ticket prices as demand for them rose, removing travel concessions for senior citizens, introducing Vande Bharat premium trains to attract a niche clientele in specific segments, ticket cancellation charges and the worst of all, replacing several sleeper and general coaches with air-conditioned coaches.

A case in point is the Howrah-Chennai Coromandel Express, with one of the longest rakes. It has 24 coaches compared to the 18 to 22 on most trains and eight or 16 coaches in the Vande Bharats. This is the train that was in the news in June 2023 as it was involved in one of India’s deadliest train accidents in recent times where the toll was close to 300.

Until some years ago, general and sleeper coaches made up close to 70% of its rake, while the rest were air-conditioned coaches. Today, that proportion stands inverted. Barely 25% of the rake is open to general and sleeper class travel.

Those who can afford only sleeper class tickets have far fewer seats that can be reserved. They end up buying unreserved tickets and travelling in the general compartments. They are also compelled to wrongfully occupy sleeper and air-conditioned compartments, including the toilets.

This story of compromised passenger safety and crushed human dignity repeats itself across many trains across India.

There are ways to set this right – ways that are evident even to us laymen. Reverting to the older system in which rakes have more general and sleeper class coaches is an immediate solution that will ease the problem of overcrowding.

A more systemic solution will be to fast-track the Dedicated Freight Corridor – dedicated lines that will only service goods trains – to free up space for more passenger trains. In 2006, approvals were given for 2,770 km to be implemented by 2011 at an estimated cost of 21,140 crore. The estimated project cost ballooned to Rs 81,459 crore as of 2015 from 21,140 crore in 2006.

After years of delay due to systemic inefficiencies, budget overruns and land acquisition troubles, this crucial project is yet to be fully operational. Eighteen years after the initial approval, about 12% of the corridor is still under construction, and a critical 500-km extension on the Eastern Corridor is still pending.

India has, meanwhile, moved on to a more shiny bullet train project between Mumbai and Ahmedabad that will cater to 35,000 passengers daily – 0.15% of the Railways’ present clientele, at an estimated cost of Rs 1,10,000 crore.

Lastly, the dedicated Railway Budget presentation, which was last tabled as a standalone speech in Parliament on February 25, 2016, must return so that the policies and allocations get more attention and scrutiny and the people can hold the ministry accountable for something that impacts them so directly.

The Railways does not feature prominently in either election manifestos of the two largest political parties in India for the 2024 general elections. The Bharatiya Janata Party’s manifesto and the “Modi ki Guarantee” slogan, while seeking a third term in office, highlights achievements that are verifiably false.

It claims large strides in rail safety over the last 10 years while, in fact, even the basic safety requirement of track renewal was less than 10% of the planned budget of Rs 58,459 crore, as explained in this article in Scroll written four months before the manifesto was published.

“More than a quarter of the 1,129 derailments that took place between 2017-’18 and 2020-’21 were linked to track renewals, according to the Comptroller and Auditor General,” states the article. It also explains what ails the Railways, from passenger overcrowding to poor finances leading to the failing rail infrastructure health and abysmal safety standards.

Several measures such as the introduction of numerous Vande Bharat and Namo Bharat trains do not benefit the average Indian traveller. A second seating or sleeper class ticket from Bangalore to Dharwad would cost less than Rs 300 whereas a Vande Bharat for the same route costs Rs 1,100. These train tickets are several times the cost of a sleeper or second seating coach, making it viable only for the rich.

The Congress’s manifesto speaks about the Railways only briefly. While it makes the right noises about upgrading the infrastructure to cater to the “common people and commuter” there is alarmingly little to explain how this will be achieved.

The unsettling images of hapless rail travelers are an indication that our trains are once again becoming the “lokhandi rakshas” of the British Raj – painfully real iron demons, petrifying and unattainable.

For a government that wishes to project an image of being a decoloniser, what we see today is a willful recolonisation of our Railways where the majority of its users just do not have a level playing field.

(Kalyan Sundareswaran and G Sriram Iyer are corporate professionals and lovers of the Indian Railways. Courtesy: Scroll.in, an Indian digital news publication, whose english edition is edited by Naresh Fernandes.)