In a year of record-breaking extreme climate events, the government continued to amend key environmental laws and provisions as part of its push for ‘ease of doing business’ – actions that contradict India’s stand on the global stage that it will move away from “business-as-usual”.

The dilutions include amendments to penal provisions in umbrella environmental laws, office memorandums and notifications which are executive orders passed to exempt certain projects from environmental impact assessment, as well as a push for infrastructure projects in eco-sensitive areas.

These developments took place against the backdrop of major events. The second part of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Sixth Assessment Report – the first after 2013 – was released in February and April. The report was a grim warning of the impact of climate change; it also presented a pathway to reduce emissions and adapt to the changing weather.

In November, countries across the world met for the 27th Conference of Parties in Egypt, where they adopted the Sharm el-Sheikh implementation plan on climate action.

In December, countries met for the first time after 2020 for the 15th Conference of Parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity in Montreal, Canada to discuss halting biodiversity loss. In December, India took over the presidency of the G20, an intergovernmental platform comprising 19 countries and the European Union, that works to address issues like climate change, the global economy and financial stability.

As the year comes to a close, we take stock of environmental developments in India over the past 12 months. We reached out to the environment ministry for their comments on December 19, and will update the story when we receive a response.

Local extreme events

This year, the country recorded extreme weather events on 241 out of 273 days (at the rate of close to one every day) between January 1 and September 30, according to a Centre for Science and Environment report released in November. These included unusually heavy rainfall, landslides, floods, thunderstorms, cold waves, heat waves, cyclones, sandstorms, squalls, hailstorms and gales. Some of the record-breaking events include the seventh wettest January, the warmest ever March, and third-warmest April since 1901.

The report also found that these events claimed 2,755 lives, destroyed over 1.8 million hectares of crop area, damaged 416,667 houses and killed 70,000 livestock. The report warned that these figures could be underestimated. In 2021, India suffered an income loss of $159 billion – 5.4% of its gross domestic product – due to extreme heat conditions, according to an IndiaSpend report published in October.

And this can only get worse. According to NASA’s temperature analysis, climate change is causing the earth to warm up at a rate of roughly 0.15 degrees Celsius to 0.20 degrees Celsius per decade. The impact of global temperature rise will continue to worsen, cautioned the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report published in February 2022.

India’s pledges

In keeping with the bold climate pledges from 2021, in August India released its updated Nationally Determined Contributions, or climate pledges, under the Paris Agreement. According to the updated Nationally Determined Contributions, India now stands committed to reducing the emissions intensity of its gross domestic product by 45% by 2030 from 2005 levels, and achieving about 50% cumulative electric power installed capacity from non-fossil fuel-based energy resources, also by 2030.

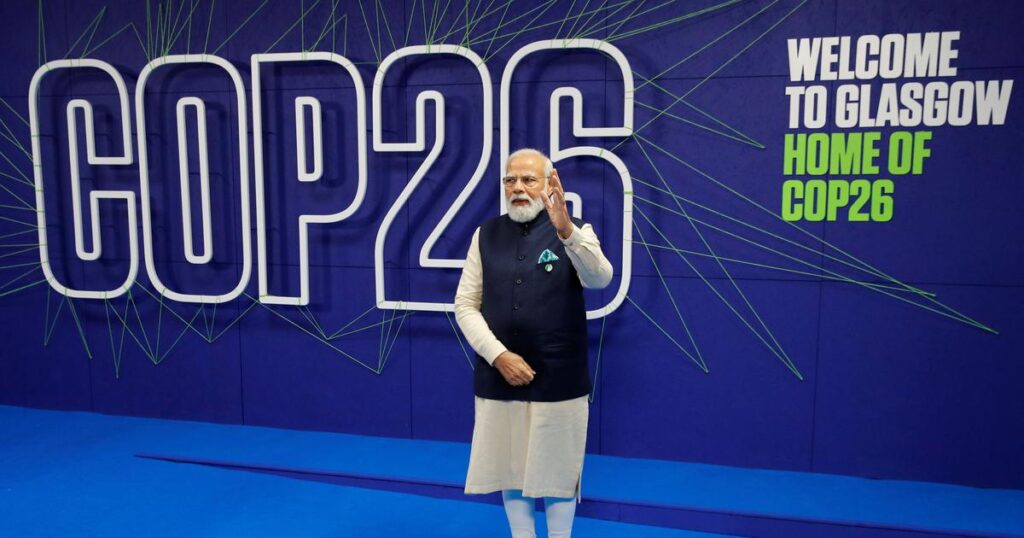

The updated Nationally Determined Contributions also include the role of healthy and sustainable lifestyle – dubbed LIFE (Lifestyle for Environment) – as a key to combating climate change. Ahead of COP27 in October, Prime Minister Narendra Modi along with United Nations Chief Antonio Gueterres launched the LIFE mission, which was heavily promoted at COP27 to position India as going beyond policy-making to advocate for individual- and community-level change to help the global fight against climate change.

LIFE’s three-pronged strategy includes nudging individuals to practise simple yet effective environment-friendly actions in their daily lives (demand), such as using public transport and choosing sustainable products like cloth bags over plastic; enabling industries and markets to respond swiftly to the reducing demand (supply) for environmentally unsustainable products like disposable/single-use products and packaging; and influencing government and industrial policy to support both sustainable consumption and production (policy).

At COP27 in Egypt India, in common with the 57 other nations attending, released its long term strategy for net-zero emissions (to become carbon neutral and thereby prevent further global heating) also known as LT-LEDS.

India’s approach is based on four key considerations that inform its climate policy landscape, namely its low historic contribution toward global warming, significant future energy needs of the country, national circumstances as it pertains to committing to low-emission growth strategies, and the need to build climate resilience. The over 100-page document specifies that it will focus on the following seven sectoral priorities including transition in electricity systems, transport and buildings, removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, financial and economic aspects of net zero targets, among others, to meet India’s decarbonisation goals.

Experts pointed out that the significance of LT-LEDS, or the LIFE movement, is that it underscores India’s commitment to depart from the “business as usual” approach. But this is contradicted by the dilutions in domestic environmental laws that are meant to benefit business at the cost of the environment.

Environmental laws diluted

In the year now ending, the environment ministry continued its push to dilute existing environmental laws.

In June and July, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change proposed amendments (here, here and here) aiming to dilute the penal provisions (which includes imprisonment of offenders) embedded in three key environmental laws–the Environment Protection Act, 1986; the Air (prevention and control of pollution) Act, 1981; and the Water (prevention and control of pollution) Act, 1974.

“Overall, environmental laws in India protect the fundamental rights of communities,” said Leo Saldanha, a Bengaluru-based policy analyst working with Environment Support Group, an non-governmental organisation that works on issues of social and environmental justice in India. “Dilutions in environmental norms or notifications have been happening since the mid 2000s, but in the last few years we have been witnessing that the parent laws, which are foundations to these notifications, are being diluted.”

The proposed changes include a proposal to remove the provision of imprisonment as a penalty for non-compliance under some sections of these Acts. For example, non-compliance under the Environment Act will currently attract fines (of up to Rs 1 lakh) or imprisonment (up to five years), or both. However, the latest amendment proposes to restrict penalties to fines alone. Similarly, under the Water Act, the amendment seeks to replace the punishment for violations with financial penalties, rather than prosecution in a court of law.

Experts note that doing away with imprisonment could affect the implementation of these Acts and encourage a pollute-and-compensate attitude. “The idea behind (dilution of penal provisions) is you can cause damage and get away without criminal punishment,” noted Saldanha.

Earlier in April, in a set of proposed notifications, the environment ministry sought to do away with mandatory environmental impact assessments before the expansion of airport terminal buildings, exempt “strategic” highway projects from the purview of environmental impact assessments, and increase the threshold limit for thermal power plants.

On April 11, the ministry issued guidelines, through an office memorandum, for exempting mining projects from mandatory Environmental Clearance in instances where the proponent seeks to increase production capacity by up to 50% of the existing threshold limit without increasing the original lease area.

“This year saw many amendments that sought concessions to companies, exemption to clearance process, dilution in public hearing, etc. All of the changes, big and small, reduce the scrutiny of the public from the project,” said Krithika Dinesh, an independent environmental lawyer and researcher. “These changes also shift the focus of environmental laws for the purpose for which it was created, which is to protect the environment to become more of an efficient clearance office”

The larger problem is that many of these key laws are amended through office memorandums, which are subordinate laws approved and changed by Ministry officials, and not amendments.

Saldhana points out that amendments to existing laws need to be tabled in Parliament. The ministry, under pressure from investors and politically vested interests, has bypassed this and routinely takes environmental decisions via notifications and office memorandums. He added, “they always result in irreversible adverse impact on fundamental rights of impacted communities. They are also unconstitutional, and the Parliament and Judiciary have to step in and stem the environment ministry’s consistent anti-constitutional behaviour”.

In December 2021, the ministry sought to weaken institutional oversight over access to and use of India’s bioresources under the Biological Diversity Act, 2002. This undermines resource-dependent people’s traditional rights over biodiversity, and could be misused by corporations, IndiaSpend reported in January.

Again in January 2022, through an office memorandum, the ministry said it will introduce a star rating system based on efficiency and timelines of states in granting environment clearances, which weakens environmental safeguards, IndiaSpend reported in January.

Apart from dilutions, the government has also sought to divert ecologically sensitive areas for infrastructure projects. This includes the proposed diversion of the Great Nicobar island for a mega project involving the construction of a trans-shipment port, an international airport, a power plant and a township spread over more than 166 sq km of land – an area that currently includes 130 square km of primary forest.

The project will witness the felling of nearly 8,50,000 trees and the reclamation of 300 hectares of land from the ocean. This will impact the nesting habitats of giant leatherback turtles and the Nicobar megapode, a flightless bird endemic to the Nicobar islands, according to the May expert appraisal committee report.

All these changes to the environmental acts will end up weakening the environment, thereby accelerating climate change and weather impact. This is in direct contradiction to what India has been promising the world that it will do.

(Courtesy: IndiaSpend, a non-profit online webportal that uses open data to inform public understanding on a range of issues, with the aim of fostering better governance and more transparency and accountability in governance.)