There is a raging debate in the country about the ‘idea of India,’ though the phrase is rarely explained by those who use it. Grasping its many meanings is left to the imagination of the context in which it is used and the audience to whom it is addressed. At times, it refers to the Indian republic founded upon the Constitution. At other times it evokes the grand vision of a timeless India with all its diversities, all its past epochs. It may refer to the many origins of India’s diverse populations and cultures, or may even be used as a synonym for what we think was or is the Indian ‘civilisation’.

Thinking of a civilisation is by no means easy. If one were to go strictly along the dictionary path, one would find that the term ‘civilisation’ is rooted in the Latin ‘civitas’, or the English ‘civil’, pointing firmly to ‘city’ as the basis of ‘civilisation’. In India, city or the urban social structure first came into existence during the Indus period, found its apex for about six centuries—from the 24th century BCE to the 19th century BCE—and declined. That was followed by a half-a-millennium-long gap, a time about which we know very little.

The next known phase of India’s prehistory emerges with the Rigveda, around the 14th century BCE, when India entered a new system in which cities did spring up but the larger population of India chose the village structure as its long-term ‘civilisational’ choice. Since then and until colonialism once again prioritised cities, for over 32 centuries, most of the knowledge production, artistic expression and metaphysical meditation continued to spring up from remote and lonely places rather than from cities. Seen from that perspective, the term ‘civilisation’ is not so adequate to encompass India’s past.

However, by ‘civilisation’ one implies ‘all that was there, great and not so great’, a pervasively binding cultural thread, and in the case of South Asia, one has to invoke language as being that principle, the elan vital, the substance and essence of the idea of India. Linguists no more like to talk of Indian languages in terms of distinct linguistic families; they have moved to describing the vast multitude of Indian languages as ‘a linguistic area’ having a far greater mutual intelligibility between a language and its surrounding languages than in most other parts of the world.

Languages in India

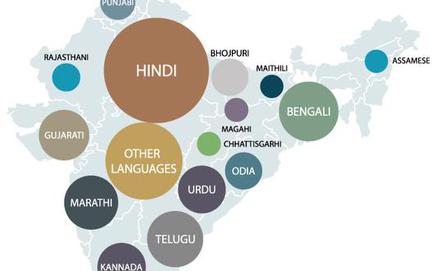

Language in India stands out not just by its great diversity but also as an unmistakable key to its cultural tensions and social stratification. Going by the estimates put forward by UNESCO and Ethnologue, there are about 7,000 living languages in the world. Of these, about 12 per cent are spoken in India. I should add that there is no decisive figure for the living Indian languages still available.

Census 2011 listed 1,369 ‘mother tongues’; but every ‘label’—name of a mother tongue as entered by people during the census—is not necessarily a ‘language’. In fact, successive governments have tried to minimise the figures by introducing absurd methods for language count. The People’s Linguistic Survey of India (2010-2013) reported 780 languages, with the caveat that the PLSI may have missed out some 70 languages. So, one can assume that there are about 850 living languages in the country.

What is most remarkable about this vast diversity is that in any given period in the past, we had a similar diversity. When Sanskrit arrived in India 35 centuries ago, there already were languages which were later identified as the Pali group of languages, Prakrits and ancient Dravidian. Besides, wherever our ancient ancestors struck roots, the ‘population knots’ formed by them gave rise to local languages. When Panini formulated his system of grammar 25 centuries before our time, he mentioned not just one but numerous language varieties.

Throughout the first millennium, works such as Matanga’s Brihad-desi and Kuntaka’s Vakrokti-jivita were built round the idea of many language varieties, and characters in plays of Kalidasa and Bhavabhuti are seen using several several languages within a single scene. During the first millennium, Al-Biruni and Amir Khushro, again, said that to be Indian meant to be speaking many languages. In the past, neither Sanskrit nor Persian, despite their metaphysical and material might, was able to replace regional and subnational languages. The Prakrits continued to exist though Sanskrit declined. Modern Indian languages of the areas ruled by Persian-speaking rulers survived while Persian all but disappeared. Colonial rule succeeded in imposing a common legal framework over the entire geographical span we call India; however, despite T.B. Macaulay’s education policy, imposing a single language was not dreamed of by the British.

Eighth Schedule

After Independence, language diversity received a constitutional validity when the Constituent Assembly decided, after elaborate debate and discussion, to introduce the Eighth Schedule containing 14 languages as deserving of recognition. The expanded list now has in it 22 languages. Nearly 30 languages are hoping to be included in it. Add to this several hundred languages of Adivasis and nomadic communities, as also the languages of the north-eastern region and the coastal communities.

While nationalism was spelt out in Europe during the 19th century in terms of linguistic unity, in India, speakers of these hundreds of different languages accepted to belong to a single nation because the Constitution promised them the freedom of expression making it mandatory on the state to encourage languages ‘without harming other languages’. Indians have been, through several millennia, multilingual in their thinking, life and habitat. The national anthem they sing with such great pride describes India primarily in terms of some of its language communities, speakers of the Punjabi, Sindhi, Gujarati, Marathi, Dravidian languages, Odiya and Bangla.

Quite evidently, Indians know that we are one nation not because we speak one language, or despite our speaking diverse languages, but because we have many languages. It was precisely for this reason that, soon after Independence, the Union government set up the State Reorganisation Commission and created ‘linguistic’ States. No patriotic Indian would ever think of our many languages as a liability or provide an apology for language diversity; that diversity makes us proud as Indians, for that was at the heart of our idea of nationalism. To look at the linguistic texture of India askance is really to reject the constitutional basis of India’s federalism.

One of the paradoxes of the Union government’s structure is that, sadly, language as a subject is divided between the Human Resource Development Ministry [renamed Ministry of Education in 2020] and the Ministry of Home Affairs. Historically, the Home Ministry has often taken an anti-language-diversity stand. After the Bangladesh war, which was fought on the question of language, the Home Ministry asked the census office to introduce a completely arbitrary cut-off figure of 10,000 for a language to qualify for being announced by the Census as a language. The absurdity needs no comment.

Recently, Home Minister Amit Shah advised States to move over to Hindi as the language of inter-State communication. To decide which language a State will use is entirely the prerogative of that State. Therefore, the Home Minister should not have invited himself to express an opinion on this issue. Not surprisingly, his comment was seen as an extension of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s majoritarian politics—Hindi being the language spoken in the country with the largest numbers—and also an articulation of the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh’s (RSS) idea of Hindi-Hindu-Hindustan nationalism as the only true nationalism. Little did he realise that deep within it is a view that goes against the very grain of Indian civilisation. India, if nothing else, is a linguistic civilisation, and its linguistic diversity is the perennial civilisational mark, its gene.

(G.N. Devy is a renowned linguist and cultural activist. Courtesy: Frontline magazine.)