Note: Throughout this article, we have preserved Bhagat Singh’s use of the word ‘untouchable’ in his writings, which reflected contemporary usage. His use of the word, and its contextual use in this article, should be read as ‘so-called untouchables’. Similarly. the phrase ‘lower strata’ should be read as ‘so-called lower strata’, ‘upper caste’ as ‘so-called upper caste’, etc.

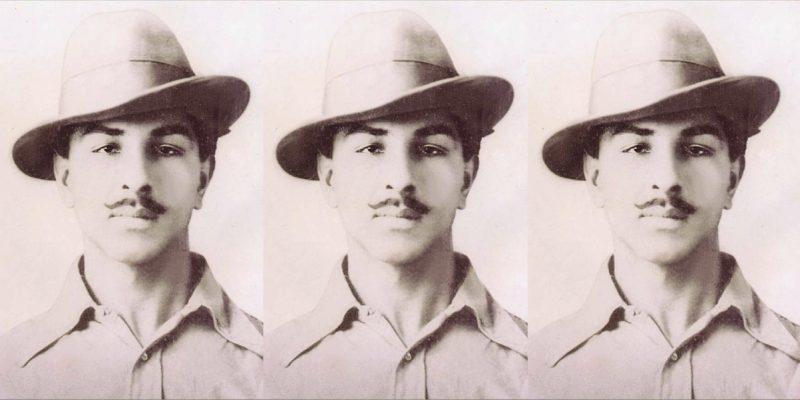

The influence of socialist and Marxist thought on the writings of Bhagat Singh has been well documented, discussed and debated. However, his thoughts, as well as that of the broader revolutionary movement, on the questions of caste and untouchability have not been paid much attention in academic as well as activist circles.

Apart from his popular article – ‘Problem of Untouchability’, published in the June 1928 issue of Kirti – there are a few other articles and essays as well where Bhagat Singh criticised caste and related aspects. And even though all his writings are in the form of pamphlets or newspaper reports and appear as running commentary, we can delineate the line of reasoning which informs his criticism of caste and untouchability.

It is one thing to criticise caste-based discrimination and atrocities from an abstract concept of ‘equality’, and completely another to criticise caste as a form of institutionalised discrimination whose legitimacy is derived from the religious doctrines of Hinduism. While the former can take place without criticising Hinduism in radical terms (eg. Vivekananda, Gandhi, Savarkar etc.), the latter has to take into consideration the roots of the caste system in Hindu religious principles and philosophy (eg. Phule and Ambedkar). Bhagat Singh’s criticism of caste and untouchability is firmly anchored in the latter approach.

Religious basis of caste/untouchability

Bhagat Singh understood caste and the practice of untouchability and its associated binary of purity-pollution as an integral part of Hinduism (Sanatana Dharma). The belief that an untouchable’s touch can pollute and destroy the ‘dharma’ of an upper-caste is criticised by Bhagat Singh at several places. ‘The Problem of Untouchability’ begins with questions like:

“Would the contact with an untouchable mean defilement of an upper-caste? Would the gods in the temples, not get angry by the entry of untouchables there? Would the drinking water of a well not get polluted if the untouchables drew their water from the same well?”

At another place critiquing the purity-pollution binary, he writes:

“…if a low-caste boy garlands people like the Pandit or the Maulvi, they have a bath with their clothes on and refuse to grant the ‘janeyu’, the sacred thread, to the untouchables…”

These practices, according to Bhagat Singh were legitimised by Sanatana Dharma, which “is in favour of discrimination of touchable-untouchable”.

At the centre of Bhagat Singh’s criticism of caste is the brahmanical theory of karma, which postulates that people are assigned caste or varna according to the merit of their previous birth. In the ‘Problem of Untouchability’, Bhagat Singh attacked karmic theodicy as the ideological edifice built to counter the resentment emerging from the discriminations of the caste system. He writes:

“Historically speaking, when our Aryan ancestors nurtured these practices of discrimination towards these strata [untouchables] of society, shunning all human contact with them by labelling them as menials, and assigning all the degrading jobs to them, they also, naturally started worrying about a revolt against this system. [They floated the philosophy of re-birth]. All this is the result of your past sins; what can be done about it? Bear if silently! and with such kinds of sleeping pills, were they able to buy peace for quite some time.”

He reiterates this point again in his 1930 pamphlet, Why I am an Atheist, where he says:

“…well, you Hindus, you say all the present sufferers belong to the class of sinners of the previous births. Good. You say the present oppressors were saintly people in their previous births, hence they enjoy power. Let me admit that your ancestors were very shrewd people; they tried to find out theories strong enough to hammer down all the efforts of reason and disbelief.”

In the same essay he goes on to criticise the varna system which fixed the task of every varna and also earmarked strict punishment for those who violated the rules. Criticising one of the most severe forms of punishment reserved for the untouchables if they even heard the vedas or other “sacred” scriptures, Bhagat Singh says that these rules and laws related with the varna system ‘are the inventions of the privileged ones’ to ‘justify their usurped power, riches and superiority’.

According to Bhagat Singh, the lower strata of the Hindu society was deliberately kept away from education by the “the haughty and egotist brahmins”, who made learning a criminal act for them.

Consequences of the caste system

According to Bhagat Singh, the institution of caste and the practice of untouchability had two negative impacts upon Indian society. Calling the practice of untouchability ‘a grossly cruel conduct’, he pointed out that it “amounted to the negation of core human values” and therefore adversely affected the “self-esteem and self-reliance” of those who were condemned as untouchables. Here Bhagat Singh acknowledged the psychological as well as mental toll resulting from caste-based discrimination.

The second side-effect of untouchability/caste was its promotion of contempt for labour, especially physical labour. This, according to him, had negatively impacted the historical economic development of Indian society. Underlining this particular consequence, he writes:

“…In broader social perspective, untouchability had a pernicious side-effect; people in general got used to hating the jobs which were otherwise vital for life. We treated the weavers who provided us cloth as untouchable. In UP water carriers were also considered untouchables. All this caused tremendous damage to our progress by undermining the dignity of labour, especially manual labour”.

The caste system, according to Bhagat Singh, was a system to extract free and cheap labour from the most under-privileged communities. Celebrating the strike of the sanitation workers of Jamshedpur, Bhagat Singh in his article ‘Satyagraha and Strike’ (1928) writes:

“…the ‘scavengers are on strike and entire city is in a mess… we do not allow these brothers who serve us the maximum to come close to us, cast them off calling ‘bhangi! bhangi! and take advantage of their poverty, and make them work for very low wages, and even without wages! They can bring the people, especially in the cities to their knees in just a couple of days. Their awakening is a happy development.”

Commenting upon the historical contribution of untouchables in progression of Indian society, he called them the “real sustainers of life…. the real working class.… the pillars of the nations and its core strength”.

Critique of upper-caste-led social reform movements

Bhagat Singh was very sceptical about various reform movements that were supposedly fighting to do away with the menace of caste and untouchability. The upper-caste led social reform movements, according to him, resulted not from any genuine concern for the untouchables, but were a reaction to the introduction of communal representation or separate electorates by the proposed Minto-Morley reforms of 1909. The communal award, as it came to be known, threatened the dominant position of upper-caste Hindus vis-à-vis Muslims and Sikhs, as the number of seats in the legislature was to be fixed in accordance with the size of the respective communities.

Since untouchables were being targeted by Muslim, Christian and Sikh missionaries with the promise of equality is social life, the upper-caste Hindus who previously did not consider untouchables as part of the Hindu fold, felt threatened in the numbers game of the electoral arena. This threat, according to Bhagat Singh, had “shaken Hindus from their complacency in the matter” and even “orthodox brahmins [too have] started giving the matter another thought” along with some self-proclaimed reformers, as they tried to remove the menace of untouchability.

But these reform movements led by upper-caste reformers were not serious and reeked of hypocrisy. To substantiate his argument, Bhagat Singh cited an incident from Patna where social reformers had gathered to discuss the problem of untouchability. When questions emerged about the eligibility of untouchables to wear sacred thread (the janeyu) or reading the vedas/shastras, a number of social reformers lost their temper and protested against the move.

Criticising Madan Mohan Malviya, who undertook campaigns to remove untouchability, Bhagat Singh further writes:

“a reputed social reformer like Pandit Malviyaji, known for his soft corner for untouchables, first agrees to be publicly garlanded by a sweeper, but then considers himself to be polluted till he bathes and washes those clothes. How ironical!”

Similarly, in another essay titled ‘Religion and our Freedom Struggle’, published in the May 1928 issue of Kirti, he writes: “…people also say that we must reform these ills [of untouchability]. Very good! Swami Dayananda abolished untouchability but he could not go beyond the four varnas. Discrimination still remained!”

Bhagat Singh was not only against the practice of untouchability, but against the entire caste system as evident from the above quote as he reprimands Swami Dayananda. In the same essay, he says that only way to do away with these problems was to oppose the Santana Dharma, which favours the discrimination of touchable-untouchable.

Advocacy of separate electorate

Bhagat Singh approached the question of separate electorates in a very positive light. According to him, the proposed communal reward was a step towards a) strengthening the untouchables as a political group and b) it would help to weaken the caste structure. He writes:

“In the context of our advance towards national liberation, the problem of communal representation may not have been beneficial in any other manner, but at least it means that Hindus/Muslims/Sikhs are all striving hard to maximise their own respective quota of seats by attracting the maximum number of untouchables to their own respective folds… all three are trying to outdo each other, resulting in widespread disturbances… this turmoil is certainly helping us to move towards the weakening of the hold of untouchability.”

Bhagat Singh was also in complete favour of the untouchables organising on their own a distinct identity. He writes:

“ultimately the problem cannot be satisfactorily solved unless and until untouchables communities themselves unite and organise…. we regard their recent uniting based on their distinct identity… as a move in the right direction… we plead that they (the untouchables) must persist in pressing for their own distinct representation in legislatures in proportion to their numerical strength… without your own efforts, you shall not be able to move ahead.”

But Bhagat Singh was also of the view that the problem of caste or untouchability could not be solved only within the legislative framework. He asks a very relevant and practical question: “can a legislature, where a lot of hue and cry is raised even over a bill to ban child marriages on the grounds that it shall be a threat to their religion, dare to bring the untouchables on their level as their own?”

In his view, those belonging to the privileged upper class/caste would always try their utmost to “keep on oppressing those below them.” Therefore, he was of the view that bureaucratic/legislative-led “gradualism and reformism shall not be of use” and only way out was to “start a revolution from a social agitation and grind up… for political and economic revolution.”

Fighting caste and untouchability in practice

It is a well-known fact that just before his execution Bhagat Singh “wished for roti cooked by ‘Bebe'(mother), which was how Bogha, a Dalit prisoner in jail, was addressed.” This was not merely a symbolic act, but formed part of a broader praxis of Bhagat Singh’s politics. The Naujawan Bharat Sabha (NBS) which was formed by Bhagat Singh and his comrades in 1926, used to organise social dinners to which people of all castes and creeds were invited and where they served each other, thereby attacking the notion of purity and pollution associated with commensality.

Bhagat Singh was also of the view that the so-called upper-caste should collectively apologise to the “untouchables” for the wrongs they had done in the past. He also believed that no ritual ceremony or acts of purification was required to consider the untouchables as equal human beings. In the ‘Problem of Untouchability’, he writes:

“…present is the moment of its atonement… In this regard strategy adopted by Naujwan Bharat Sabha and the Youth conference is, most apt – to seek forgiveness from those brethren, whom we have been calling untouchables by treating them as our fellow beings, without making them go through conversion ceremonies of Sikhism, Islam or Hinduism, by accepting food/water from their hands.”

In his article ‘Religion and our Freedom Struggle’, Bhagat Singh says that the “meaning of our freedom is not only to liberate ourselves from the clutches of the English but also complete independence, when all people live together harmoniously, liberated from mental slavery”. Here the term “mental slavery” is related to the hold of religion as well as the practice of untouchability in society, as he writes that cooperation and unity against the British is possible “by leaving aside our narrow-mindedness… by changing partisan food habits and removing the words touchable-untouchable by their roots”.

Further, in the historic meeting held at Feroz Shah Kotla in Delhi in 1928, where the Hindustan Republican Association (HRA) was transformed into Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA) and socialism was adopted as its official ideology and goal, another historic decision was taken in regards to caste and religion. It was decided that the revolutionaries would discard all symbols of religion and caste. Again, this decision to discard religious and caste symbols was not an impromptu decision taken by the Bhagat Singh and his contemporary revolutionaries.

Even before these historic decisions , the revolutionaries of the Hindustan Republican Association (HRA) like Rajendranath Lahiri, Manmath Nath Gupta, Keshav Chakravarty and others (all sentenced under the Kakori Conspiracy case) had thrown away their sacred thread, the ‘janeyu’. As I wrote in an earlier article with Ankur Goswami:

“That the HRA revolutionaries used to break Brahminical socio-religious conventions is also confirmed by Gupta in his autobiography They Lived Dangerously. Gupta writes, ‘We used to take beef in defiance of the whole society. This does not mean that all our members were of this view.’ Even though the ‘old’ members did not support the eating of beef, they did not impose their beliefs among the ‘young’ members who were experimenting with revolutionary ideals in every aspect of life. According to Gupta, the ‘old’ members tried to dissuade the ‘young’ revolutionaries, not by citing ‘religious codes’ but through debates and discussions over the merits of eating non-vegetarian food.”

Conclusion

Bhagat Singh’s criticism of caste and untouchability is not merely a class- or economic-based criticism or criticisms based on an abstract idea of equality. Instead, he attacks the very foundation of caste and untouchability by attacking the philosophical, religious and spiritual rationale of caste system as enshrined in Brahmanical religious scriptures.

Further, Bhagat Singh also understood caste also as an ideological system which functioned to justify and legitimise the prevailing economic inequality. This was an extension of his criticism of religion, which according to him was a tool for manipulation. Clearly, his views of caste and religion, as far as their ideological function is concerned, was clearly inspired from the Marxist framework. He did not limit himself to an economic understanding of caste, but also acknowledged its cultural and psychological impact.

Bhagat Singh understood caste in a comprehensive manner, and his solution too was of comprehensive nature. He did not create the binary of cultural-economic or political-cultural or economic-political while commenting on caste. Caste, at once was a social, cultural, economic and political issue and the only way to deal with it was by taking all these seemingly disparate spheres as a whole.

As in the end of his article on untouchability, Bhagat Singh exhorted the untouchables to “raise the banner of revolt” and “challenge the existing order of society” with the famous quote from the Communist Manifesto: “Workers unite – you have nothing to lose but your chains”, but added an important addendum that, “you are the real working class”. He was of the firm view that only a working class revolution with ‘untouchables’ at its axis could free India from both capitalist and caste exploitation.

(Harshvardhan is a research scholar. Article courtesy: The Wire.in.)