“…[T]here are two types of human relations and the obligation to remember is not moral but ethical. I try to make memory and communities of memory a basic unit. The notions of nation and community rely upon the idea of community of memory. I think that the discussions about what is a nation and what is ethnic, if a nation is ethnically based or whatever, should rely upon the idea of whom we think belongs to the same community of memory. An identity, namely a group identity, for me depends on the idea of a community of memory.”

– Marglit Avishai

We started from home for Mandi House. We were late. The march was to start at 11 am. Suddenly, a message from a friend popped up in my inbox, telling me that the demonstrators had been detained by the police and the march was disrupted. He advised me not to go to the protest site.

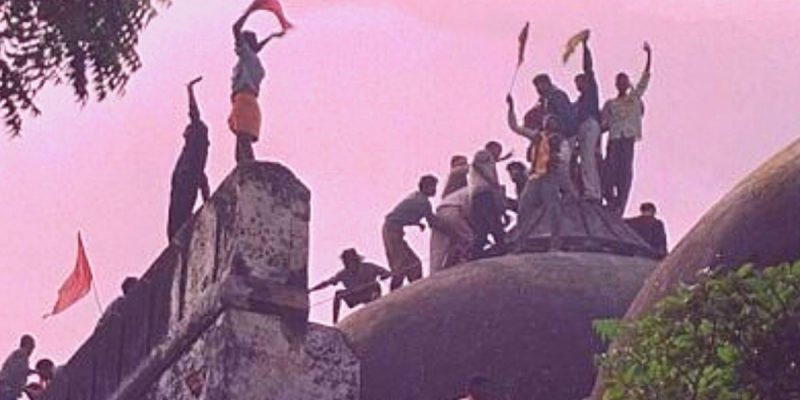

It was December 6. We wanted to remember the sixth of December, 1992. Together. A day when a mosque was torn apart, razed to the ground by hundreds of goons under the watch and open instigation by leaders of a political party which is now ruling India. One of them, riding on this wave of hatred, became the deputy prime minister of India and was in charge of the home ministry. Rakesh Batabyal had likened nation building to home making, in his essay from Nehru’s India: Essays on the Maker of a Nation. Here was a man who had created walls in this home and was later assigned to supervise its functioning. Another one of the hate mongers became the education minister of India and equated intellectuals with terrorists.

There was also the presence of an absence. The absentee legitimiser of the politics of hate. Who made hate against Muslims palatable to those who wanted to be known as decent people. He had flown away from the place of the atrocity after cleverly instigating his crowd the previous evening to raze the ground where the Babri Masjid stood. The man rose to be the Prime Minister of India. He was used as an excuse by a great many people to support his politics of division and hate. They argued that not everything could be appalling about a party which had a “poet” like him at its helm.

The man in question brings to the mind another absentee participant in this act: the invisible hand of the Supreme Court. The man had, in his exhortation, told people that what was to be done the next morning was nothing but an implementation of the order of the Supreme Court to do ‘kar seva‘. The wise heads had permitted kar seva on the site where lakhs of people had been mobilised as part of a long campaign of hatred against Muslims. It was not reverence or love for Lord Ram which had brought them to his imagined land of birth but a pent up desire to put Muslims in their place in India – to humiliate and subjugate them. If the honourable justices could not foresee what their permission would ultimately do, can it be dismissed as a mere error of judgement?

This ostensible lack of judgement is further reinforced by the fact that the Supreme Court did not think it was necessary to punish those who had violated the undertaking to ensure the safety of the mosque. That case is still lingering in the Supreme Court. Rakesh Bhatnagar recalls his interaction with Justice Venkatchaliah and Justice G. N. Ray who were astonished that the Supreme Court could be treated in this manner by a state government.

The Supreme Court, however, never corrected this ‘mistake’ on their part. It only perpetuated it. Last year on November 9, it handed over the land on which the Babri Mosque had stood for more than five centuries to those who had demolished it. The order which accepted the status of the VHP representative as the guardian of Lord Ram who was to be ‘given back’ his birth place demonstrated that the crime of the demolition of the mosque had been legitimised.

The Supreme Court has again allowed the central government to go ahead with another kar seva, this time in Delhi while placing a condition before it not to demolish or construct anything for its dream project, the Central Vista. Some will argue that the issue in question is an entirely different matter and any reference to demolition of the Babri Masjid, while discussing it, is unwarranted. But is the similarity entirely misplaced?

How does one recall December 6? As an event or as a milestone of a process in which nearly all actors of Indian politics played their role? Was it only the political class? Could December 6 be possible without active complicity from the Hindi media? We, who rue the downfall of the media in our times, forget that it had long been acting as the mouthpiece of the ideology of hate against Muslims.

So, when we remember December 6, we understand that we never seriously attempted to define the content of a decent society that we should have become. For us there was no non-negotiable. The ideology of hatred against Muslims always got its validation by those who called themselves ‘secular’ or ‘humanists’. Can we imagine December 6 without the date when the lock on the Babri Mosque was removed under the leadership of a moderniser prime minister, a nice loveable man?

Remembering December 6, therefore, not only entails condemning active criminals but also those who made it possible for the crime to happen in the first place, those who allowed it to be done on their behalf.

There were dates before December 6 and after December 6 which give meaning to it. February 28, when the Gujarat pogrom started, August 5, when Jammu and Kashmir was dismembered and downgraded, November 9, when the land of the Babri Mosque was granted to the demolishers, December 11 when the Citizenship Amendment Act was passed in the parliament.

It is important to remember December 6. But now the number of those who have borne this memory is dwindling. We did not hear any major political leader, barring a few left leaders, talking about the meaning of December 6 for us. The Congress wants us to ignore it, for the regional parties it is too national a date to stir their partial memory, for the media there are far too pressing and relevant issues vying for its attention. Good natured and peace loving people will advise us to forget the day to make living possible.

A life which does not examine itself is no life. Memories help us in this act of scrutiny. If an event or a date evokes two disparate and antagonistic memories in two sections of society, it is impossible for us to become one people.

December 6 is a date which forces us to think about our laziness, our compromises and our complicity which led to a crime which was not inevitable. It could have been pre-empted and prevented. December 6 was a culmination of events which could not have been possible without well thought out decisions and was also the beginning of the processes which have led us to the present state – a situation in which all of us feel trapped.

There is a responsibility we have with our memories of December 6. What is that? It has do with the damage that it was meted out to our cognitive and affective faculties. It is a task to create a decent society. A society in which atonement is possible and memories are not tools to humiliate a section of society and isolate it.

Remembering December 6 is, in the words of Marglit Avishai, a necessary step in creating a community of memory, a moral task, of moving away from the thick to the thin and feeling responsible towards each other.

(Apoorvanand teaches at Delhi University.)