Denise Comanne

Patriarchy

The oppression of women is very ancient: it existed before capitalism, which is also a system of oppression, but one that is more global in nature. Patriarchy can be defined in simple terms as the oppression and objectification of women by men. In addition to its strictly economic form, this oppression is expressed in many ways, notably through language, kinship relations, stereotypes, religion, and culture. The form oppression takes varies depending on whether you live in the North or the South, or in an urban or rural area.

The revolt against oppression or the feeling of being exploited does not inevitably result in the questioning of patriarchy (nor does the oppressed working class simply decide to put an end to capitalism; yet it is surely easier to react against being oppressed by the boss than by one’s partner). Before such questioning can be formulated, the most common explanations must be brushed aside, whether based on physiology (different sexual organs or brain) or psychology (a nature said to be passive, docile, narcissistic, etc.), to lead to a political critique of patriarchy as a dynamic system of power, capable of perpetuating itself, and which resists any transformation of its core assertion of male supremacy. [1]

To be a feminist is thus to become aware of this oppression and, having realized that it is a system, to work to destroy it to help bring about the emancipation (or liberation) of women.

Characteristics of patriarchy [2]

Male domination cannot be reduced to a sum of individual acts of discrimination. It is a coherent system that shapes all aspects of life, both collective and individual.

1) Women are “overexploited” in their workplace, and in addition they perform many hours of housework, but housework does not have the same status as paid work. Internationally, statistics show that if both women’s paid professional work and their housework are taken into account, women are “overworked” compared to men. The separation in terms of household chores and family responsibilities is the visible face (thanks to feminists) of a social order based on a sexual division of labor, that is a distribution of tasks between men and women, according to which women are supposed to devote themselves first and foremost and “quite naturally” to the domestic and private sphere, while men devote their time and efforts to productive and public activities.

This distribution, which is far from being “complementary”, has established a hierarchy of activities in which the “masculine” ones are assigned high value and the “feminine” ones, low value. There has in fact never been a situation of equality. The vast majority of women have always performed both a productive activity (in the broad sense of the term) and various household tasks.

2) Domination is characterized by the complete or partial absence of rights. Married women in 19th century Europe had almost no rights; the rights of women in Saudi Arabia today are virtually non existent (generally speaking, women who live in societies in which religion is an affair of the State have very limited rights).

The rights of Western women have increased considerably, partly under the influence of the development of capitalism, which needed them to work and consume “freely,” but even more, as a result of their own struggles.

Women have continued to struggle collectively for more than two centuries to gain the right to vote, work, unionize, exercise their motherhood freely, and to full and total equality in the workplace, family, and public sphere.

3) Domination is always accompanied by violence, which can be physical, moral, or in the realm of ideas. Physical violence may be conjugal violence, rape, or genital mutilation: this violence can go as far as murder. Moral or psychological violence may be insults or humiliations. In the realm of ideas, violent acts are represented in various ways, such as in myths and various forms of discourse. For example, among the Baruya (an ethnic group from New Guinea) where male domination is omnipresent, women’s milk is not considered to be their own product but the transformation of male sperm. Obviously, this representation of milk as being a ‘by-product’ of sperm is a form of appropriation by men of women’s power to procreate. It is also a way to codify the subordination of women in the representation of the body.

4) Relationships based on domination are often accompanied by discourse that represents social inequalities as natural. The effect of this discourse is to make people accept these inequalities as an inevitable destiny: they have natural origins, and cannot be changed.

This type of discourse can be found in most societies. For example, the Ancient Greeks referred to the categories of ‘hot’ and ‘cold’, and ‘dry’ and ‘moist’ to make a distinction between “masculinity” and “femininity”. Aristotle offers the following explanation: “The masculine is hot and dry, associated with fire and a positive value; the feminine is cold and moist, associated with water and a negative value (…).” It has to do, he says, with a different nature in their aptitude to ‘cook’ blood: women’s menstruations are the incomplete and imperfect form of sperm. The perfect/imperfect, pure/impure relationship Aristotle establishes between sperm and menstruations (and therefore between the masculine and the feminine), has its origins in a fundamental biological difference.

Thus, a form of social inequality codified in the social organization of the Greek city-state (women were not citizens) is transcribed as being natural, through the representation of the body.

In other societies, other “natural” qualities are associated with men and women, also resulting in a hierarchical ordering of the two genders. To cite one example, in Inuit society, the cold, the raw, and nature are associated with men, whereas the hot, the cooked, and culture are associated with women. Just the opposite is true in Western societies, in which man is associated with culture and woman with nature. We can thus observe that with different “natural” qualities (cold and hot for women, for example), the ultimate result is always a hierarchical social order of men and women, and whatever the “natural” quality may be, it is always less good in women.

My goal is not to deny that there are biological differences between men and women; however, observing a difference does not mean automatically accepting that there is inequality. Likewise, when a set of “natural differences” is exaggerated in a society, not between various individuals but between social groups, we must suspect that there is a social relationship of inequality hidden behind the discourse of difference.

This discourse of “naturalization” is not specific to the dominance-based relationship between men and women; it may also be used to refer to the situation of blacks. For example, some discourses have justified the various forms of exploitation and oppression of blacks by referring to their congenital “laziness”. A similar assertion was made about workers in the 19th century: at that time, their inability to escape from poverty was explained by the fact that in was in their “nature” to be drunkards from father to son.

This type of discourse tends to transform the individuals involved in social relationships into “species” with definitive “qualities.” As these qualities have natural origins, they cannot be changed, which justifies and legitimates the inequality in relationships of exploitation and oppression.

5) If there are no social struggles, discourses based on “naturalization” can be easily internalized by the oppressed. For example, as far as women are concerned, there is the commonly held idea according to which it is because they bear and give birth to children, that they are “naturally” more gifted than men for taking care of them, at least when they are young. However, young women are often as unprepared as their spouse in the first days after a child is born. On the other hand, they have often been prepared psychologically (through education and the norms that permeate society) for this new responsibility, which is going to require them to learn new skills. This distribution of tasks concerning young children (which means that women are almost exclusively responsible for the actual care given to babies) is not in the least bit “natural”; it is a question of social organization, of a collective choice made by society, even if it is not explicitly formulated. The result is well known: it is mainly women who must do what they can to “reconcile” professional work and family responsibilities, to the detriment of their health and professional situation, whereas men are deprived of this continuous contact with their young children.

This naturalization of social relations is unconsciously (subtly) codified in the behavior of the dominant and the dominated, and pushes them to act in accordance with the logic behind these social relations: in Mediterranean societies, for example, men must obey the logic of honor (at any moment, they must be ready to prove their “manliness”), whereas women must adhere to the code of being discrete and docile while serving others.

The result of this discourse of “naturalization”, expressed by the dominant, is that individuals of both sexes are labeled, assigned a single identity, and in some cases persecuted or at least mistreated, in the name of their social origins, the color of their skin, their gender, sexual orientation, etc. In Western societies, the white, middle class, Christian, heterosexual man has been, and is still to a large extent the reference model. Only a person with these types of characteristics could (can) pretend to be a complete individual who can speak for humanity. All the others – blacks, Jews, gypsies, gays, immigrant workers and their children, and women (who can in fact be burdened by several of these “afflictions”) – had to, and must still today, justify themselves to enjoy the same rights as the dominant group.

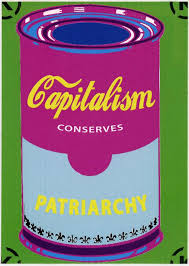

Where Capitalism Comes in

In the past, when children were asked on school questionnaires what their parents did for a living, they were told to leave a blank for their mothers if they were housewives. There could be no better emblem than that “blank” for the invisibility of women’s work in the domestic sphere in capitalist societies before the revival of feminism in the late ’Sixties. Feminists were the ones who drew attention to the importance and diversity of women’s unpaid activities in the home.

It would be hard to put a figure to women’s invisible contribution, not usually considered in terms of monetary value since neither buying nor selling comes into it; however the UNDP in its 1995 report evaluated it at an estimated 11,000 billion dollars. This figure must be seen in relation to that of world productivity, estimated at the time to be around 23,000 billion dollars, in order to get an idea of how much women contribute to humanity as a whole. (UNDP, 1995, p. 6).

To these 11,000 billion dollars should be added women’s contribution to the economy in monetary terms (for example in the form of paid employment). Lastly, it should be recalled that in general women are paid less than men for the same or equivalent work.

Housework involves the tasks that reproduce the workforce – tasks that are carried out within the family home. 80% of such domestic tasks are carried out by women, and by far the greatest proportion of this work by women is UNPAID. Somehow the capitalist system has never envisaged transforming domestic tasks into professional employment remunerated with a salary and/or by marketable products.To bring off such a tour de force has required that, through the patriarchal values underpinning our society, men and women accept and develop the idea that women are naturally predisposed to accomplishing domestic chores.

The issue of women’s domestic work in the private sphere is thus central to any analysis of their situation.

The capitalist system’s propensity to reorganise the economy on a global scale to its own profit has direct repercussions on gender relations. Analysis of its methods shows that, on the one hand, the capitalist system feeds on a pre-existing system of oppression – patriarchy – and on the other, it compounds many of its defining characteristics. The oppression of women is a tool which enables capitalists to manage the entire workforce to their own profit. It also enables them to justify their policies when they find it more profitable to shift the responsibility for social welfare from the State and collective institutions to the “privacy” of the family. In other words, when the capitalists need extra labour, they call upon women whom they pay less than men, which has the side-effect of dragging down wages generally. This means that the State is forced to provide services to facilitate women’s jobs or allow them to offload some of their responsibilities. Then when they no longer require women’s labour, they send them home, back to their “proper place” in patriarchal terms.

There is not yet a country in the world, even among the most advanced in this area, where women’s pay is equal to men’s. Indeed some industrialized countries are seriously losing ground in comparative terms of human development, regarding this criterion: Canada has slipped back from the 1st to the 9th place in world ranking, Luxemburg has fallen back twelve places, the Netherlands sixteen and Spain twenty-six (UNDP, 1995). Careers where women are in the majority in fields such as health care and education are devalued.

When capitalism is in crisis, austerity measures are introduced whereby women are the first to be excluded from social benefits such as unemployment benefits, for example, where they exist. Elsewhere, they are pushed into very poorly-paid jobs such as work in the free zones. In Mexico in this sector women’s salaries have collapsed from 80% to a mere 57% of men’s. They may also be won over by the idea of doing a good job for a pittance among the multitude of jobs in the informal sector, beyond the pale of “paralysing ” State regulations.

Women’s rights in the workplace are undermined by a thousand government tricks. There is of course the “choice” of working part-time which extends from half-time to the “zero” contract where the female worker remains at the boss’s disposal to work from zero to any number of hours as required; this despite the fact that practically all surveys show that the majority of working women would like a full-time job. The increasing reduction in services such as crèches and day-nurseries, or the privatisation of others such as rest-homes for the elderly, have led to a multiplicity of pitfalls for working women. “Equality at work” has had the negative effect of introducing more night-work for women. Of course it was right to establish equal working conditions for women in the security and health services, and so forth; but what was also at stake with these so-called egalitarian measures was to allow women to work on the line in night-shifts, for example. There is absolutely no vital imperative to build cars at night. The new measures establishing male-female equality should then have been – in clear-thinking feminist terms – to eliminate night-work for men. Moreover, for most women this night-work on the line, unacceptable on principle, makes life intolerably hard most of the time, in view of the work women still have to do in the domestic sphere.

The issue of women’s work in production, or the public sphere, is therefore just as central.

To manage this issue, capitalism uses patriarchy as a lever to attain its objectives, while at the same time reinforcing it.

The fact that women are relegated – by patriarchy – to domestic tasks allows capitalists to justify their over-exploitation and under-payment of women with the argument that their work is less productive than men’s. They invoke weakness, menstruation, absenteeism for pregnancy and maternity leave, breastfeeding, and caring for sick children and older relatives. This is where the woman’s salary is denigrated as being “for extras”. Even today, with equal qualifications and for equal hours, women are paid about 20% less than men. This holds a double interest for capitalists. On the one hand, they have a cheaper, more flexible labour pool that can be used or laid off according to market fluctuations; on the other hand, this enables them to bring down rates of pay generally.

The general issue of women’s work in the private and public spheres thus reflects either their oppression, as for example when policies of the far right or religious fundamentalism force them to remain in the home; or their liberation, as in the case of progressive policies of equal pay, job creation and free public services.

******

Having duly noted the importance of domestic work, the feminist current “class struggle” gives the following analysis [3] :

- The oppression of women preceded capitalism but the latter has profoundly modified it.

Housework, in its true sense, came into being with capitalism. By largely replacing small-scale commercial production in the domains of agriculture and the crafts with big industry, capitalism made the separation between the sites of production (the workplace) and of reproduction (the family) increasingly distinct, assigning to women the role of responsibility for the home. This new ideology of the housewife, which started in the bourgeoisie, bred disdain for the woman who “had” to go out to work, not having a husband to support her. This ideology was not confined to the bourgeoisie but also spread through and contaminated the emerging workers’ movement. However, contrary to popular belief, women in the lower classes never stopped working, caught in the web of contradictions linked to their tasks within the family and their difficult working conditions. This is why we feel that the articulation between capitalism and patriarchal oppression must be analysed as a single phenomenon.

Capitalism is a dynamic and aggressive mode of production which as such, penetrates all social relations. For example, capitalism did not hesitate to make mass calls for very cheap female and child labour in the early 19th century, in order to increase production and thus profits. Throughout the centuries, this quest for maximum profits has led capitalism to undermine (at least partially) paternal and marital authority, making working women “free” to sell their labour without their husband’s permission and to become fully-fledged consumers.

This call for women’s labour underwent new developments in the early ’Sixties and again in the present day on a global scale. With the delocalisation of traditional or cutting-edge industries, in North Africa, Latin America or Asia, employers, in search of new profits, recruit young women into the labour market. These young, exploited, working women have nevertheless been able to acquire a certain financial independence from the men of the family, leading them to demand freedom in many domains.

At the same time, in the developed capitalist countries, more and more of the activities previously kept within the family are externalized, taken care of in the first instance by public services such as schools and health institutions, or increasingly dealt with through the market: the making of clothes, meals, and so on.

- The oppression of women is useful to the capitalist system.

Capitalism, while favouring a certain emancipation of women for the sake of profit, nevertheless remains very attached to the traditional family institution. Why?

- In our societies, the family plays a fundamental role in reproducing the divisions, as well as the hierarchy, between the different social classes and genders to which different social and economic functions are assigned. In the name of the “maternal” function, women must take on all the tasks related to maintaining and reproducing the workforce and the family. As for men, they are always supposed to be the main economic purveyors. All this makes it possible, in the context of professional segregation and in the name of the so-called complementary roles, to carry on underpaying women on a discriminatory basis.

- Family also plays its part in “regulating” the labour market. In times of economic expansion, as was the case for about thirty years until the early 1970s, women are massively called upon as cheap labour in a number of manufacturing industries such as electronics, then as wage-earners in the service industry. But in times of economic recession, as over the last thirty years, employers and the State unrelentingly suggest that women should – partly or completely – withdraw from the labour market to devote themselves to their “natural” vocation as mothers. When there are signs of economic recovery (however short-lived), some collective investments are again considered, not with regard to gender equality, but in order to “release” female labour and subject it to flexible schedules.

- At all times, women’s domestic labour makes it possible for the State to save in terms of collective facilities and for employers to lower wages. If women were not perceived as those who are in charge of those chores within the family, a substantial reduction of working time for all and a significant development of social facilities would have to be introduced.

- The function of authority played by the family has been largely impaired by recent developments in the status of women in society; it has shifted to an “affective” function. Nonetheless, partisans of the capitalist social order do not hesitate to defend a family order based on hierarchical differences between genders. For instance, the hottest partisans of the traditional family consider that rehabilitated paternal authority ought to dam and wall in the possible outbursts of anger among marginalized youths in the poorer urban areas.

- Lastly, and this may at first seem to contradict the previous point, the family offers a huge advantage: it is a relatively flexible institution (its forms have significantly diversified over the past thirty years). It can be used as a safety valve for the constraints wage-earners have to face on the workplace. Most people can choose neither their work, nor their working conditions. In times of unemployment “choices” are at their most limited. But when people “choose” a spouse, when they “choose” to have children, to eat this rather than that, to buy this brand of car, to go on holiday in that country (for those who can afford it), they can feel as though they were retrieving some of the freedom they have lost outside the family. Advertising is intended to maintain this illusion. This sense of freedom is still limited by essential factors: financial resources, gender and age. Because they are still seen as responsible for domestic chores, and because of the domestic violence they are still too often subjected to, women know all too well the limits of their freedom. Children too, since some (particularly girls) are subjected to their parents’ authoritarianism, if not to physical punishment.

These various elements go some way to explaining why the family is still a fundamental support to capitalist society.

Therefore, contrary to what some feminists seem to believe, it is difficult to imagine how the liberation of women (of all women, not just of a tiny minority), could be achieved in a capitalist system. This is why we deem it necessary, whatever the conflicts involved, to bring together the struggle of women against patriarchal oppression and the struggle of wage-earners against capitalist exploitation. As an illustration of how difficult such convergence can be: some male trade unionists do not think it “proper” that women should be factory workers or are not ready to join a women’s struggle, arguing that it is through the “global” (i.e. men’s) struggle that women stand to make benefits. Moreover, some men still enjoy “ruling the roost” at home.

Historical Background

1. In the beginning…

The position of women in so-called primitive societies (prehistoric times)

Subsistence economies (e.g. hunter-gatherers)

There was no accumulation, but a constant search for resources, for ways of staying alive. Everybody’s “labour” was needed to ensure the tribe’s survival. Nobody could appropriate resources without endangering collective survival. This made for social equality.

What was/is the position of women among hunter-gatherers? According to what we read in works by anthropologists and historians:

- in the primitive group, we observe mobility among male and female individuals, with free adhesion and no discrimination;

- however where hunting became predominant in the social organization, abduction of women was practised so as to ensure the necessary reproduction of men;

- other instances, such as the importance of goddesses in mythology, tend to show that women were given social recognition.

The first farming communities: cooperative organization of labour

Social gender equality and collective property of resources and means of production were still the rule, with land, too, a collective property for common use.

Such societies did have some sort of division of labour between men and women. Women had specific tasks such as ploughing the fields, pottery and weaving, but such gender division did not result in the oppression of women or in their exclusion from the public arena and their confinement to the family circle.

Not only did women take part in productive activities but they still played a part in the social organization:

- they were members of the village council;

- some societies were matrilineal (line of descent through mothers);

- in some societies the education of children was a collective responsibility.

However, in some of these societies men could be observed taking over power so as to control reproduction and thus keep up the number of producers. The “circulation of women” had to be regulated so as to avoid the disappearance of some groups, either violently through abduction, or non violently through “exchanges” or trade.

2. Social surplus production and the emergence of social classes. Ancient societies.

The accumulation of resources, the development of productive forces and tools (time not required for survival could be devoted to designing and making tools), led to surplus production. This resulted in social classes since some considered this surplus as their own property and wanted it to increase.

At the same time (in Antiquity, around 3500 BC) we observe the development of slavery – first of prisoners from conquered territories and peoples; later also because of unpaid debts – and of the State. The function of the State was to guarantee that ruling classes could maintain their ownership of social surplus through institutions that excluded other members of the community from political functions: power belonged to hereditary lords, kings or noblemen. They set up an army, a civil service, a judiciary power, and producers of ideology (scholars, teachers) who were to make sure that the domination of those who appropriated wealth was accepted by all.

For instance, the Egyptian pharaohs relied on scribes to compute the amount of crops harvested so that part of it could be kept for ruling classes, and on a clergy who taught that any uprising against Pharaoh – God’s representative on earth – would be punished in the after-life.

The position of women changed radically:

- generalized patrilinearity: the new notion of inheritance and the transmission of property through the male line led to the importance of having male offspring whose lineage was beyond contest. Women then became pieces of property themselves, since they were perceived as mothers first and foremost, and at the same time, fathers acquired absolute power over their children (see Roman law and the abduction of women, for instance the story of the battle between the Horatii and the Curiatii).

- marriage became a source of property and wealth: for instance, the bride price that in matrilinear societies consisted of a gift, became cattle or land.

As ancient societies developed, rich owners acquired public responsibilities and political functions; women were excluded from them (no voting rights) and were made responsible for the home so that men could be freed from any domestic chores to assume their responsibilities outside and freed from the responsibility of educating children to ensure the transmission of property.

It could be objected that this only concerned women of the ruling classes. Indeed the other women worked in the fields, in manufacturing or in the silver mines (in Athens, for example). But in those cases, too, working women also had to do the household chores because there was no longer cooperative organization of labour (the family remained a production unit) – and they were also assigned the role of reproducing the labour force.

This is how the notion of women as responsible for the private sphere “indoors” developed. This is the beginning of women being enclosed within the family (which is not the same as ‘housewife’): women as child-bearers – in charge of transmitting property… or of reproducing the labour force.

3. Precapitalist societies. Feudal societies

The situation of women changed in the course of time.

In rural societies there was still a gender division of labour.

We note that women:

- still had the function of reproducing the labour force. The father’s authority over the family also corresponded to this control over the function of reproduction ;

- became specialized in domestic chores while also being involved in productive activities. Indeed the family was still a unit of production and consumption, the two being closely related, with some goods intended for family consumption and others for exchange purposes.

During this period the situation of women was in fact fluctuating and contradictory: they were kept indoors and excluded from public life, but the family was a shifting entity; for instance, widowhood and remarriage were frequent; enlarged families or family regrouping were needed to survive and produce; there were ties of solidarity. So at times, women were subjected to less pressure: e. g. the education of children might be collective. In some cases their productive labour was recognized: e.g. women could be members of guilds and corporations.

4. The period of commercial capitalism and factory development

As commercial capitalism took form, followed by mechanization, the situation of women deteriorated. Moreover, the role of the family was to change with the formation of the bourgeois State.

With the growth of manufacturing, workers/producers were separated from their means of production; craftsmen rented out their labour yet no longer owned their own tools.

This process began with “home-based industry“. Merchants rented out production equipment (for example, a weaving loom) to the family, brought them the raw materials and would come back to collect the finished product in exchange for wages.

Another consequence of manufacturing growth was that the family was transformed from a production unit to a consumption unit.

Beforehand, peasant families produced the necessities of life. In the process of capitalist development, products once produced within families were produced outside the home.

From then on, domestic labour became devalued, viewed as not producing goods which could be destined for exchange, and no longer recognized as socially necessary.

Much later on, this devaluation would impact all the professions linked to tasks seen as women’s work within families: cleaning – care-giving – teaching…

Once female work had been devalued over this transitional period, the bourgeoisie began to use women as supplementary labour, less well paid, to put pressure on male wage-earners and thus dividing the future working class, whether in the home-based industry, which still existed, or in factories.

In order to ensure acceptance of making the female workforce a reserve workforce (assigning a permanent supporting role to women’s and girls wages and work), it was necessary to clearly assign family duties to women as their main task.

From the 18th century, “focusing on the family” played an important role in the development of bourgeois society.

This represented a new conception of the family and of women’s role: the ambitions of the bourgeoisie as they became the dominant class gave rise to a new focus on the child, for children were to embody status-seeking projects. Concretely, that meant limiting the number of births “to better care for children” and enjoy a more intense home life. From this standpoint, bourgeois marriages were above all business arrangements and the family also became the means of passing on social norms. At this time, (the 18th century) this bourgeois family model only existed amongst the dominant classes. This would change.

5. The industrial revolution and proletarianization of women

At the time of factory mechanization during the industrial revolution, the bourgeoisie advocated the bourgeois family model for the working class:

- Nuclear family (parents and children)

- Women had to ensure the reproduction of the labour force: the men must be rested and ready to ensure production; children, as future producers, could no longer run through the streets and fields: they had to be prepared for their turn to go down the mines.

This family was increasingly defined as a private sphere, a consumption unit, and it played an educational role based on reproduction of the dominant ideology’s standards: respect for the established order and for private property. Within the working class family, the father could rule as the master and leave external political authority to others.

However, these plans clashed with the reality of the industrial revolution, which made women proletarians too. Indeed, at the time of 19th-century industrial expansion, everyone was mobilized to work in mines or the textile industry… including women and children. They were confined to tasks that were often dangerous, for lower wages.

The working class family was torn apart by:

- Workers’ mobility;

- Single migrants rooming in families;

- Working-class districts where a community life developed;

- Different working hours, meaning members of a family saw each other very little or not at all.

All this constituted a series of perils for the bourgeoisie who were no longer in control of the situation. In reaction, they strove to find ways to implement moral improvement as a means of regaining control over workers:

- Attempts to reform the family: the bourgeoisie promoted the housewife’s image as moral guardian. This ideology meant all women, whether or not they were part of the labour force, had to view home life as their main responsibility.

- The creation of public schools had an ideological function (Jules FERRY and the teaching of morals) and an economic function (training skilled workers) at the end of the 19th century and above all in the early 20th century.

This implies that:

- women were also responsible for a “moral influence” over men (for example, bosses would plead with women to put pressure on their husbands not to go on strike, in the name of family “survival”);

- their work was seen as a “second job”: their main responsibility, not being production, meant that their wage was an extra wage on top of the male breadwinner’s; the notion of a supplementary workforce implied that they were hired or laid-off according to current economic needs.

- work carried out by women would gradually change and be concentrated in “women’s jobs”, extensions of their roles within the family. Such work would remain underpaid as it was seen as the extension of non-productive activities, and undervalued due to its connection to family chores.

The mass entry of women in factories could contribute to their emancipation. To hamper this emancipatory process, the bourgeoisie not only resorted to “confining” women to the family, but women’s underpaid labour would also be used to divide workers. For example, dismissing men in order to make women and children work night shifts, in the worst of conditions.

6. The situation on the eve of World War I…

Many women worked and were grossly exploited, as supplementary labour.

The family was given pride of place: women were to be in charge of the family, which was:

- the place where the workforce was reproduced and maintained;

- a unit of consumption;

- the space where ideological control was exercised (this educational function was shared with schools which also reproduced the labour force and ruling-class ideology).

7. Changes in the 20th century

The mass entry of women to factories, and later offices, created the preconditions for emancipation.

Little by little, women have achieved legal equality, e.g. the right to vote in 1948 in Belgium.

Since 1945, more and more women have worked, on a lifelong basis. Women’s struggle for emancipation developed, the women’s movement was formed and progress was achieved, such as:

- the women’s strike at the National Arms Factory (NF) in Herstal (Belgium) in 1966: it was the first step towards equal pay…which remains to be accomplished.

And since 1968, there has been further progress, such as:

- contraception, decriminalisation of abortion;

- women speaking out against the double working day;

- the provision of public facilities;

- education, access to higher education, access to the professions. Women have mobilised within trade unions and political parties.

Women work more and more, but in periods of crisis, especially since the beginning of the 1980s, one can see that once again, as in the 1930s, women are seen as a supplementary workforce, and more emphasis has been put on the family and women’s role in the home.

In fact:

Since the beginning of the 1980s, the increase in part-time work (in 1995, 88% of part-time workers were women) has been presented as a means of reconciling professional and family life; on top of this, career breaks and parental leave mean fewer hours worked.

It is also important to note that women represent 40% of the working population but 28% work part-time, that is, almost a third of working women.

Many women have accepted a part-time job on the condition of receiving an added “unemployment” benefit for involuntary part-time work. Now that part-time female workers have filled these positions, this benefit has been withdrawn!

Management interests:

- dual management of labour : when restructuring, the owner imposes part-time work on… women

- flexibility: number of hours and flexible time scheduled depending on demand, on production needs.

Management and government propaganda revived the second wage concept by encouraging families to tighten their belts around one salary, the man’s income. In countries such as Belgium, this has resulted in such cutbacks as lower unemployment benefits for women and exclusion of many unemployed women living with a man earning a salary; cuts to women’s pensions; subsidies for hiring of part-time workers; encouraging single-income families (wages being earned by men) through tax incentives (a single income, divided between a couple, is charged less total tax than the sum of two incomes; this is called a dependent’s allowance).

There is a particular threat to women’s employment, which also makes public spending cuts possible (public facilities are another target to add to the above).

Despite the very fragile achievements of women, men are taking umbrage. They feel uneasy, threatened and, for example, challenged in relation to their role as father (one must not forget that patriarchy also involves father/child domination), or even seeing these timid feminist victories as attacking their status. One current of thought seeks to unite men against the feminist trend: this is the so-called “men’s rights” movement4. This shows patriarchy’s great capacity to adapt to social change. It is a reactionary movement, detrimental in terms of social relations between women and men. In relation to this, female and male feminists must rise to the question, “What type of man can smash patriarchy and play a part in women’s struggle for emancipation?”

Footnotes

[1] Jean Batou and Magdalena Rosende in Solidarités, http://www.solidarites.ch/solinf/123/10.php3

[2] This part of the training module is based on France Arets’ work, The Origins of Patriarchy, Private Property, and the Nation, in École Che Guevara, “Understanding the world to take action, taking action to change the world”, Léon Lesoil ASBL training

[3] This “radical” current of feminism (see C. Delphy in a seminal article entitled “L’ennemi principal” (The Principal Enemy)[1970]) adduced that there exists a mode of domestic production distinct from the capitalist mode of production. According to this analysis, all women, of whatever social class, are victims of direct exploitation by men within the family, and women, like men, constitute a same-sex class. In the struggle against exploitation, women oppose the class of men, just as workers oppose employers, in the class struggle. The political conclusions of this analysis were clear: in this class struggle, women should unite to combat their principal enemy, patriarchy. C. Delphy saw no immediate interest in or possibility of connecting the traditional class struggle with the struggle of the “sex classes”.

(Denise Comanne was a militant feminist active in local and international struggles against capitalism, racism and patriarchy. She was one of the founders of CADTM along with Eric Toussaint and others. She died on 28th May 2010.)