Vijay Prashad

As we enter the new year, protests across the planet continue unabated; rising levels of discontent are manifest in both progressive and reactionary directions. The political character of the anger might whip across the spectrum of opinion and hope, but the underlying frustrations are similar. There is anger at the decades-long crisis of capitalism, and anger at the consequences of austerity. Some of that anger is directed towards hope for a world without inequality and without catastrophe; some of that anger deepens into a toxic hatred of other people.

Toxic anger whips against immigrants and minorities, festering hate as a false hope against austerity. Genuine hope is to be found in the plea for a new system to better organise our common resources to end hunger and dispossession and to manage the great catastrophes of capitalism and climate change.

No surprise that young people are on the streets with banners that plead for a new world, for it is these young people who recognise that their lives are at stake, that the class realities of property and privilege are shutting the doors on their aspirations (a new UN report on Chile says that socio-economic inequality is the main grievance of the protestors). This is not a youth uprising without a class character; these young people know that they will not be able to easily access housing and work, joy and fulfilment.

The rational kernel of genuine hope points its fingers at obscene social inequality. Each year, the financial news service Bloomberg produces its Billionaires Index. This year’s index, which was published in the last days of 2019, shows that the world’s top 500 billionaires increased their wealth by $1.2 trillion; their wealth is now at $5.9 trillion, up by 25%. The largest number—172—of these 500 billionaires live in the United States. They added $500 billion to their fortunes; this includes Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, who added $27.3 billion and Microsoft’s Bill Gates, who added $22.7 billion. Eight of the ten richest people on the planet are U.S. nationals (from Jeff Bezos to Julia Koch).

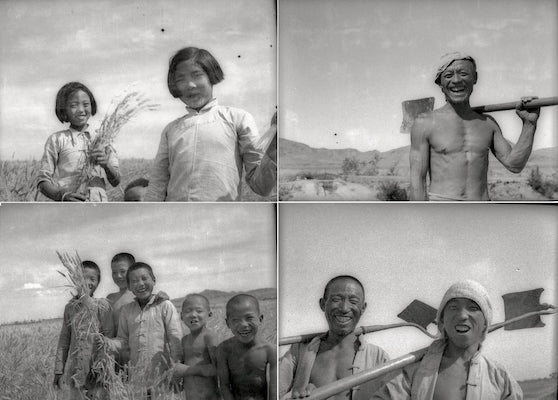

Such reports do not explain anything; they merely offer us a window into Richistan—the country of the very wealthy. But a deeper look into these numbers provides an understanding of the essence of social inequality. The Walton family, which owns the global retail giant Walmart, is well-represented in the Bloomberg list of billionaires. This family appropriates $70,000 per minute, or $100 million per day. This is the lion’s share of Walmart’s earnings. A comparison between the share of Walmart’s earnings that is seized by the Walton family and the share left to the Walmart workers is instructive. Walmart’s own Economic, Social, and Governance Report (2019) admits that the average wage for Walmart workers in the United States is $14.26 per hour. If the average Walmart employee (2.2 million of them globally) worked for 40 hours a week for 52 weeks, the employee would earn $29,660 annually—what the Walton family makes in twenty-five seconds. A Chinese worker who produces goods for the Walmart global value chain makes—on average—$300 per month, or $3,600 annually—what the Walton family makes in three seconds. The wealth of the Walton family is a direct consequence of the social labour of the millions of workers who make the products that Walmart sells and of the millions of workers who sell these products. But they earn a fraction of the vast profit of $510 billion earned by Walmart in 2019.

Last year, in January, thousands of Bangladeshi garment workers—the majority of whom are women—began industrial action against factories that made clothes that are sold by retailers such as Walmart and H&M. In retaliation for these strikes, 7,500 workers were dismissed by the owners, while thousands of workers faced criminal cases for what Human Rights Watch called ‘broad and vague’ allegations. Most of these workers earn not more than 3,000 taka a month (US $30), a tenth of the wages of a Chinese worker. When these workers—paid extremely low wage rates—ask for modest wage increases, they face the full wrath of the owners of the small factories that produce for Walmart backed by the repressive power of the Bangladeshi State.

Bloomberg’s list should be annotated to include the other side of wealth, the garment workers in Bangladesh whose social labour is seized to produce the wealth for the Walton family. It should somehow find a place for the name Sumon Mia, a Bangladeshi garment worker who died when police opened fire on striking garment workers on 8 January 2019.

A World Bank report in 2019 showed that eight million Bangladeshis are no longer living under the poverty line. This report’s main point—the decrease in poverty—hides its actual findings. One in four Bangladeshis remain below the poverty line, and 13% of the population is living under the extreme poverty line. The numbers regarding the decline in poverty are untrustworthy—the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies points out that the government data on which they are based is neither reliable nor consistent.

The protests of the workers in Bangladesh to increase their wages to a decent standard are part of the worldwide wave of anti-austerity protests. Demonstrations not only decry cuts in government spending and the rise in prices of basic goods (public transportation) but also demand the rights of workers. These struggles that have inflamed Chile and Ecuador, Iran and India, Haiti and Lebanon, Zimbabwe and Malawi, are not just against bribery or against fuel price rises; they are against the entire framework of austerity and the harsh rate of exploitation that immiserates a greater share of humankind.

The revolutionary Bangla poet, Nazrul Islam (1899-1976), sang with indignation at this robbery:

Beton Diacho? Chup rou joto mithyabadir dal!

Koto pai diye kulider tui koto crore peli bol!

(Have you paid wages? Shut up you gang of liars!

How many millions did you make for the pennies you gave the coolies!)

His poem begins with a worker getting beaten by a boss. Nazrul Islam, who never let such atrocities numb him, writes with great feeling: ‘My eyes well with tears; will the weak get beaten like this all over the world?’. He hopes that this condition is not eternal, that the exploitation of humanity is not permanent. These hopes—written into poetry a century ago—remain alive today as young people sincerely, and not naively, struggle to build a new world.

But what would that world be like? Simply being against exploitation and against oppression is not sufficient. We will need to build a socialist world …

(Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor and journalist.)