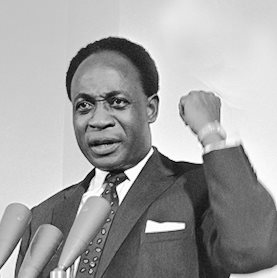

Fifty-five years ago on this day, the fate of Africa was irrevocably altered when the CIA sponsored a 1966 coup d’état against Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, former Prime Minister of Ghana and Pan-Africanist visionary who was voted as “Africa’s Man of the Millennium.”

At least 1,600 Ghanaians died in the coup and scores more were injured.[1]

Nkrumah wrote in his book Dark Days in Ghana that

It has been one of the tasks of the CIA and other similar organizations to discover… potential quislings and traitors in our midst, and to encourage them, by bribery and the promise of political power, to destroy the constitutional government of their countries.[2]

But in 1999, Nkrumah’s claim was borne out when the U.S. government declassified the Western-orchestrated plot to get rid of the man who was “doing more to undermine our interests than any other black African.”[3]

The U.S. government was determined to depose Nkrumah before he managed to unite Africa under one government, working with allies such as Great Britain and Canada to finance, mastermind, and guide the coup.[4]

According to the U.S. State Department at the time, Nkrumah’s “overpowering desire to export his brand of nationalism unquestionably made Ghana one of the foremost practitioners of subversion in Africa.”

Nkrumah’s Bureau of African Affairs allegedly had 100 agents supporting

nationalist and… opposition movements in such African states as the Ivory Coast, Upper Volta, Niger, Togo, Senegal, Cameroon, Liberia and Nigeria with the ultimate goal of assisting more radical elements in gaining power and ultimately of achieving a Nkrumah monopoly in Africa.[5]

He was even mounting an offensive against apartheid South Africa, furnishing money and sabotage training to “extremists” in the African National Congress (ANC) bent on overthrowing the white supremacist regime.[6]

In the years leading to the coup, the State Department withheld loans to Ghana and worked to lower world cocoa prices through stockpiling in order to deprive Nkrumah of foreign exchange.[7] The British press reported that 40 CIA officers operated out of the U.S. Embassy “distributing largesse among President Nkrumah’s secret adversaries,” and that their work “was fully rewarded.”[8]

John W.K. Harlley, a main coup plotter, was “an excellent [U.S.] embassy contact for important police matters,” who profited from diamond smuggling.[9]

According to Nkrumah, Harlley orchestrated the coup to block investigation into his corrupt practices by Attorney General Geoffrey Bing, who was detained after the coup, and whose secretary was forced to destroy records of the investigation.

Harlley in turn claimed that he launched the coup because he had proof of corrupt practices by Nkrumah and his ministers, and that the coup was thus a legal act.[10]

CIA Deputy Director Ray Cline had advocated for “discreet contact with opposition groups outside Ghana,” and with members of the armed forces.

He devised a scheme calling for “illegal seizure of control by Convention People’s Party (CPP) radicals” in the event of the “death or removal from office of the president” which would force a “strong reaction” among the military against the radicals; an immediate period of confusion and uncertainty might follow, with a power vacuum that would “seem to offer the greatest possibility for the introduction of external influences.”[11]

On February 6, 1964, when the coup against Dr. Kwame Nkrumah was being planned, William C. Trimble, then director of the State Department’s West African Desk, wrote a memo to his bosses entitled “Proposed Action Program for Ghana,” which said in part:

Although Nkrumah’s leftward progress cannot be checked or reversed, it could be slowed down by a well-conceived and executed action program. Measures which we might take against Nkrumah would have to be carefully selected in order not to weaken pro-Western elements in Ghana or adversely affect our prestige and influence elsewhere on the continent. U.S. pressure, if appropriately applied, could induce a chain reaction, eventually leading to Nkrumah’s downfall. Chances of success could be greatly enhanced if the British could be induced to act in concert with us.[12]

Baffour Ankomah, the editor of New Africa Magazine, goes on to note:

Intensive efforts should be made through psychological warfare and other means to diminish support for Nkrumah within Ghana and nurture the conviction among the Ghanaian people that their country’s welfare and independence necessitates his removal.

A year later, the policy had worked so well that the American Ambassador in Ghana, William Mahoney, was able to tell the CIA director, John McCone, at a meeting in McCone’s office on March 11, 1965, “popular opinion is running strongly against Nkrumah, and the economy is in a precarious state.” [13]

Prior to the declassification, John Stockwell, a CIA officer in Africa had recounted the plot to undermine Nkrumah’s government and to sow anti-Nkrumah sentiments among Ghanaians.

Stockwell wrote:

Howard Bane, who was the CIA station chief in Accra, engineered the overthrow of Kwame Nkrumah. Inside the CIA it was quite clear. Howard Bane got a double promotion, and was awarded the Intelligence Star for the overthrow of Kwame. The magic of it was that Howard Bane had enough imagination and drive to run this operation without ever documenting what he was doing and there wasn’t one shred of paper that was generated that would name the CIA hierarchy as being responsible.[14]

Recent research conducted by Yves Engler shows that the Canadian government played a major role in this conspiracy against Nkrumah. Engler writes:

As the 1960s wore on Nkrumah’s government became increasingly critical of London and Washington’s support for the white minority in southern Africa. Ottawa had little sympathy for Nkrumah’s pan-African ideals and so it made little sense to continue training the Ghanaian Army if it was, in Kilford’s words, to ‘be used to further Nkrumah’s political aims.’ Kilford continued his thought, stating: ‘that is unless the Canadian government believed that in time a well-trained, professional Ghana Army might soon remove Nkrumah.’[15]

On the day of the coup, the CIA and British intelligence spread stories that 11 Russian security men had been killed defending the presidential house, but a mortician testified that the only white corpse he examined had died of natural causes.[16]

Robert Komer, then a deputy national security adviser and later the head of the Phoenix program in Vietnam, wrote a congratulatory assessment to President Lyndon B. Johnson on March 12, 1966 that

the coup in Ghana is another example of a fortuitous windfall. Nkrumah was doing more to undermine our interests than any other black African. In reaction to his strongly pro-Communist leanings, the new military regime is almost pathetically pro-Western.[17]

The U.S. embassy had long played up Nkrumah’s alleged economic mismanagement and poor human rights record, although it tolerated a higher number of political prisoners among the military junta which succeeded him and worse economic outcomes.

The National Liberation Council (NLC) that took over was advised by Harvard University economist Gustav Papanek, who was fresh from a stint in Indonesia. He recommended the privatization of state-owned businesses, enabling the restoration of foreign dominance of Ghana’s economy, as the country was reoriented toward the West.[18]

Governmental corruption in the illicit diamond trade was rife and strikes were brutally suppressed by USAID-trained police under the new order.[19]

The New York Times reported that the coup caused a “wild day” in cocoa futures, with prices rising and speculators rushing in to take their profits; the cancellation of cocoa deals with Eastern bloc countries made the commodity more widely available for sale to Western markets.[20]

American ambassador, Franklin H. Williams, a black pioneer in the State Department, considered the coup the “greatest opportunity we have had to date to enhance U.S. policy objectives in Africa,”[21] which were deeply unpopular.

One of the main coup plotters wrote less than a year after the coup that “the irony of the present situation is that it is quite probable that President Nkrumah and the CPP would command the support of a majority of the electorate … in genuinely free elections. It is a pity that it is not possible to test this hypothesis.”[22]

A Man of Destiny

Nkrumah was born in the small village of Nkroful in the western region of the Gold Coast (now Ghana) probably on September 21, 1909.[23] His precocious mind led him to gain admission to Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, one of the premier historically black colleges in the U.S.[24]

As he grew into adulthood, Nkrumah developed a noble vision for Africa and the Black race. He saw the metropolises of Africa becoming the headquarters of science, technology, and medicine. He saw in Africa a giant hypnotized, rendered dormant by years of foreign tutelage and exploitation, and he sought to awaken this giant.

In hindsight, Nkrumah can be seen as one of the most illustrious makers of modern Africa and among the most ardent and consistent advocates of the unity of the Black race after Marcus Garvey.

But time and his contemporaries were not on his side. As celebrated British historian Basil Davidson put it: Nkrumah lived far ahead of his time.

Of course, Nkrumah, was not a paragon of political virtue; he made mistakes, including his allowing bootlickers and sycophants in his party to make a god out of him and to tear him away from the ordinary people.[25] But the positives greatly outweigh the negatives.

Nkrumah’s single-minded desire to make Africa the proud home of all people of African descent dispersed around the world brought him to work with many leaders and architects of the Pan-Africanist movement, including W.E.B. Du Bois of the United States, George Padmore of Trinidad, Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, and Nnamdi Azikiwe of Nigeria.

He was one of the organizers of the historic 5th Pan-African Congress in Manchester, England, in 1945.

It proved decisive in the struggle against foreign rule in Africa and against racial oppression in the West and demonstrated a remarkable unity between continental Africans and Africans in the Diaspora.[26]

Not only did Nkrumah bring Pan-Africanism to its natural home when he returned to the Gold Coast after his sojourn in America and England to lead the independence movement, he also established and sustained until the end of his regime a link between the continent and the Diaspora.

He borrowed many brilliant ideas from his inspirer and admirer Marcus Garvey, including the Black Star as a national symbol (displayed in the center of Ghana’s flag as well as taken as the names of the country’s shipping line and soccer team).

He made Padmore his adviser and invited the grand old man of Pan-Africanism, Du Bois, to live out his last days in Ghana.

In Africa, Nkrumah attempted to form the kernel of his pet dream—the United States of Africa—with Sekou Touré of Guinea, Modibo Kieta of Mali, and Patrice Lumumba of the Democratic Republic of Congo.[27]

Without doubt, Nkrumah ranks among the greatest political figures of the 20th century. An indefatigable champion of world peace, advocate and spokesman of the Non-Aligned Movement, it is ironic that his government was overthrown in the violent CIA-masterminded coup while he was on his way to Hanoi to negotiate a peaceful settlement to the U.S. war in Vietnam.

His courageous and tactical leadership (Gandhian non-violent passive resistance or what he termed “positive action” leadership) led to the wresting of the political independence of his country from Britain, the first such achievement in sub-Saharan Africa.

Ghana’s independence not only became the powder-keg that ignited a continental revolution against European imperialism, Nkrumah also consciously made his newly liberated country the powerhouse of the African revolution.

Nkrumah’s revolutionary and pan-Africanist ideas swept across the entire continent, from Casablanca to Cape Town.

Consistent with his independence-day declaration that the independence of Ghana was meaningless unless it was linked with the total liberation of the entire African continent, Nkrumah trained African liberation fighters, financed their movements, and encouraged them to dislodge colonial rule from their territories.

It was no wonder that in less than a decade after Ghana’s independence in 1957, more than 90 per cent of African countries had attained their own independence.

All of Nkrumah’s adult life was devoted to one and only one passion—the liberation and unity of the African race. He lived, dreamed, and died for this ideal. His passion and quest for a continental union government prompted his enemies to brand him a dreamer, a megalomaniac, an African Don Quixote.

But judging from the parlous state of the continent’s 54 desperate, dispirited, non-viable countries today, Nkrumah’s call for the formation of a United States of Africa government was a wise one, if brazen at the time.

The largely ineffective African Union is testimony to Nkrumah’s warning that only a continental government of political and economic unity could save the continent from the encircling gloom spawned by enraging internecine civil wars, civil strife, famine, and disease.[28]

Nkrumah argued forcefully that only a federal state of Africa, based on a common market, a common currency, a unified army (an African High Command), and a common foreign policy could provide the launching pad for not only a massive reconstruction and modernization of the continent, but also could optimize Africa’s efforts to find its rightful place in the international arena and so effectively checkmate internal conflicts, fend off superpower interference, and predatory and imperialistic wars.[29]

What Might Have Been

From the moment that Nkrumah ascended to power in Ghana, as its country’s first post-colonial leader, the CIA’s eyes were tracking him and what was happening in Ghana from faraway Virginia.

According to Baffour Ankomah, in December 1957, just nine months into independence, the CIA issued a report on Ghana which was distributed within the American government and intelligence community.[30] Prescient, the report states that “the fortunes of Ghana—the first tropical African country to gain independence—will have a huge impact on the evolution of Africa and Western interests there.”[31]

It did not take long for that prediction to come true. Within ten years of Ghana’s independence, 31 other African countries had gained their own independence.

And Nkrumah’s Ghana (which, in his own words, “we have got to make our little country an example for the rest of Africa”) had had a huge role in liberating Africa. He set up training camps in Ghana for African freedom fighters, and through financial, political, and other support, Nkrumah’s Ghana kept the African liberation torch burning brightly.

True to his electoral promises, Nkrumah went to work putting the economic and social fundamentals in place. This encouraged the people to work even harder.

Nkrumah firmly believed that political independence was meaningless without economic independence.[32]

Thus, by the time he was overthrown in the CIA-inspired coup, Ghana had 68 sprawling state-owned factories producing every need of the population—from shoes, to textiles, to furniture, to lorry tires, to canned fruits, vegetables, and beef; to glass, to radio and TV; to books, to steel, to educated manpower, virtually everything![33]

Nkrumah wanted to industrialize Ghana within a generation, and everything was on course until the Americans and their British cousins (according to their own declassified documents) used some disgruntled and self-serving Ghanaian soldiers to stage that terrible coup on February 24, 1966 that truncated Ghana’s progress. It was a major setback, not only for Ghana but the whole of Africa!

As Baffour Ankomah rightly observes: “If Nkrumah had been allowed to complete his industrialization plan, Ghana would today have been another Malaysia on the west coast of Africa, and the modern doomsayers who now mock at Ghana by showing us the bright lights in Kuala Lumpur, would not dare show their warped tongues!”[34]

But Nkrumah was overthrown, and we are now left with nostalgia and what might have been.

After the coup, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) rubbed salt into our injuries by sending a delegation to Accra to tell the military junta to discontinue Nkrumah’s industrialization program, which they did.

And, as a reward, some of them got airports named after them! Today, 55 years after the coup, almost every Ghanaian (except those still suffering from acute blindness and amnesia) now realizes our great loss.[35]

Notes:

[1] Kwame Nkrumah, Dark Days in Ghana (New York: International Publishers, 1969).

[2] Nkrumah, Dark Days in Ghana; John Stockwell, In Search of Enemies: A CIA Story. (New York: W.W. Norton & Co. 1984), 201.

[3] https://wikispooks.com/wiki/Document:US_Role_in_Nkrumah_Overthrow

[4] Document:US Role in Nkrumah Overthrow

[5] “Ghanaian Subversives in Africa,” February 9, 1962; “For Mac Bundy, State Department Draft Study on Ghana” RG 59, Gen. Records of the Department of State, Records of the Bureau of African Affairs, 1958-1966, National Archives, College Park, Maryland (hereafter “NA”), box 65.

[6] Olcott Deming to Mr. Fredericks, “CAS Report on Sabotage in South Africa,” January 11, 1962, RG 59, Gen. Records of the Department of State, Records of the Bureau of African Affairs, 1958-1966, NA, box 50. Joe Matthews was one of the “extremists” who received $10,000 from Ghana for anti-government operations in Basutoland.

[7] Nkrumah, Dark Days in Ghana, 95.

[8] These CIA officers included Thomas J. Gunning, Edward Foy, both former army intelligence officers, William B. Edmundson and Ms. Stella Davis. Kwesi Kwaa Prah, The Social Background of Coups D’état (Brazil, Indonesia, Ghana). Center for Advanced Studies of University of Amsterdam, 1973; Stockwell, In Search of Enemies; Richard Mahoney, JFK: Ordeal in Africa (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983); Seymour Hersh, “CIA Said to Have Aided Plotters Who Overthrew Nkrumah in Ghana,” in Dirty Work 2: The CIA in Africa, Ellen Ray and William Schaap, Eds. (Secaucus, NJ: Lyle Stuart, 1979); C.M. Jones to Marvyn Brown, “British Embassy Paris,” March 3, 1966, British National Archives, Kew Gardens.

[9] American embassy Accra to Dean Rusk, Secretary of State, February 26, 1966, RG 59, Gen. Record of the Department of State, Records of the Bureau of African Affairs, 1958-1966, NA, box 2236; Nkrumah, Dark Days in Ghana, 42-43.

[10] See Geoffrey Bing, Reap the Whirlwind: An Account of Kwame Nkrumah’s Ghana from 1950 to 1966 (London: MacGibbon & Kee, 1968).

[11] Ray S. Cline, Deputy Director Intelligence, Memo for Director Intelligence and Research, Department of State, January 29, 1963, “State Department Draft Study on Ghana” RG 59, Gen. Records of the Department of State, Records of the Bureau of African Affairs, 1958-1966, NA, box 2139.

[12] https://www.modernghana.com/news/116308/24th-february-a-dark-day-in-our-national-history.html. Accessed on January 28, 2021.

[13] https://www.modernghana.com/news/116308/24th-february-a-dark-day-in-our-national-history.html. Accessed on January 28, 2021.

[14] https://www.modernghana.com/news/363669/the-cia-kwame-nkrumah-and-the-destruction-of-ghana.html

[15] As cited in Yves Engler (2015) https://www.pambazuka.org/pan-africanism/canada%E2%80%99s-role-overthrow-kwame-nkrumah Accessed on January 28, 2021.

[16] Hersh, “CIA Said to Have Aided Plotters Who Overthrew Nkrumah in Ghana,” in Dirty Work 2, Ray and Schaap, Eds.

[17] “The CIA, Kwame Nkrumah and the Destruction of Ghana,” November 28, 2011, https://www.modernghana.com/news/363669/the-cia-kwame-nkrumah-and-the-destruction-of-ghana.html; Kwame Nkrumah, Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism (New York: International Publishers, 1965), 4.

[18]“Detainee Describes Experience in Prison,” American embassy document, June 23, 1966; “Seventy More Persons Released from Protective Custody,” December 8, 1966; RG 59, U.S. State Department, Africa Bureau, NA, box 2237; Prah, The Social Background of Coups d’état (Brazil, Indonesia, Ghana) (Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam, 1973). After the coup investors flocked into the country, including William H. Beatty, Vice President of Chase Manhattan Bank, who spoke of new favorable investment conditions as a result of the remarkable strides made since the coup.

[19] See Jeremy Kuzmarov, Modernizing Repression: Police Training and Nation Building in the American Century (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012), ch. 8. British colonial police officers and Israeli Mossad also trained the Ghanaian police, working closely with Harlley. L.A. Hicks, “The Ghana Police Service,” September 1969, British National Archives, FCO 065/119, Kew Gardens.

[20] Elizabeth M. Fowler, “Commodities,” New York Times, February 25, 1966, 46.

[21]“New Decree Gives Police Powers to Army Officers,” American embassy Accra, December 25, 1966; American embassy Accra, March 26, 1966, RG 59, Gen. Record of the Department of State, Records of the Bureau of African Affairs, 1958-1966, NA, box 2236; Richard Eder, “U.S. Officials Show No Regret Over the Removal of Nkrumah,” New York Times, February 24, 1966.

[22] Ahmad Rahman, The Regime Change of Kwame Nkrumah: Epic Heroism in Africa and the Diaspora (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), xiii.

[23] Charles Quist-Adade, “Kwame Nkrumah, the Big Six, and the Fight for Ghana’s Independence,” Journal of Pan-African Studies, 1, 9 (August 2007), available at: https://law-journals-books.vlex.com/vid/kwame-nkrumah-fight-ghana-independence-60327957

[24] Rahman, The Regime Change of Kwame Nkrumah, ix.

[25] Quist-Adade, “Kwame Nkrumah, the Big Six, and the Fight for Ghana’s Independence.” See also Ruth First, Power in Africa (New York: Pantheon Books, 1970).

[26] Quist-Adade, “Kwame Nkrumah, the Big Six, and the Fight for Ghana’s Independence.”

[27] Quist-Adade, “Kwame Nkrumah, the Big Six, and the Fight for Ghana’s Independence.”

[28] Quist-Adade, “Kwame Nkrumah, the Big Six, and the Fight for Ghana’s Independence.”

[29] Quist-Adade, “Kwame Nkrumah, the Big Six, and the Fight for Ghana’s Independence.”

[30] As cited in Baffpir Ankomah, “Ghana Celebrates, Africa Rejoices,” New African, Issue 460, March 2007.

[31] Kwame Nkrumah, Axioms of Kwame Nkrumah (London: Panaf Books, 1980).

[32] Baffour Ankomah, “Ghana Celebrates, Africa Rejoices,” New African, Issue 460, March 2007.

[33] Ankomah, “Ghana Celebrates, Africa Rejoices.”

[34] Ankomah, “Ghana Celebrates, Africa Rejoices.”

[35] Charles Quist-Adade, “The Coup That Set Ghana and Africa Fifty Years Back,” Pambazuka News, March 2, 2016, https://www.pambazuka.org/governance/coup-set-ghana-and-africa-50-years-back.

(Charles Quist-Adade is an educator, author, researcher, and social justice specialist and advocate. He currently teaches sociology at Alexander College in Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada. Article courtesy: CovertAction Magazine, a US non-profit organisation.)