In October 2021, a Belgian environmental inspector opened a container at the port of Antwerp that, according to its manifest, was supposed to contain bales of mixed paper waste from Canada.

It was one of 20 containers from the Saint-Michel recycling centre in Montreal that were destined for India.

“Oh it really stinks!” said Marc de Strooper, taken aback by the stench of garbage.

As he looked closer, de Strooper found a mess of broken glass, old clothes, metal debris, broken toys and used medical masks. He also saw paper bales that contained a large quantity of difficult-to-recycle plastic bags.

“Canada is known as a beautiful country with lots of nature lovers. I don’t understand how they can produce garbage like this,” de Strooper said. He stopped the containers from moving on to their destination and they still sit at the port.

Canada has become one of the biggest exporters of recyclable paper to India — with Quebec and the city of Montreal sending much of their mixed paper waste to that country.

An investigation by Radio-Canada’s Enquête shows that much of what is supposed to be paper actually contains tonnes of plastic bags, some of which litter the Indian landscape, and are often burned as a source of fuel.

Rules around the international plastic waste trade were tightened a few years after China closed its borders to most foreign recycling in 2018.

That waste then flooded countries like Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines. It caused a series of scandals and those nations severely restricted plastic imports.

Canadian companies still export large amounts of mixed paper that are often contaminated with plastic. Some appear to ignore international plastic restrictions — with few penalties when they are caught.

Over the last five years, 123 paper-and-plastic bales were returned to Canada because they did not meet standards, yet the federal government has only issued six warning letters.

India, with lax inspection in some of its ports and a huge appetite for paper fibre, has become an attractive destination for Canadian recycling, with roughly 500,000 tonnes of mixed paper bales exported there between April 2019 and 2021.

By law, these bales can include junk mail, office paper and paperboard packaging. Although Indian rules say they can have only two per cent contamination, some of the bales entering are stuffed with large amounts of hard-to-recycle plastic.

The city of Montreal is considered among the worst offenders when it comes to shipping off contaminated bales of paper.

The city’s two recycling centres — in Lachine and Saint-Michel — average between 20 and 26 per cent contamination, according to numbers provided by the city.

“If you have 25 per cent of a bale’s mass that is not paper, there were major defects when the bale was collected,” said Marc Olivier, a professor in management of residual materials at a Quebec research centre, the Centre de transfert technologique en écologie industrielle in Sorel-Tracy, Que.

According to de Strooper, this paper should not be classified as recyclable but rather as mixed waste or hard-to-recycle plastic, the import of which is prohibited in countries like India without their prior consent. He has formally requested that the Italian-based paper dealer send the shipment back to Canada.

“What will they do with the non paper waste (in India), could it end up being dumped or burned out in the open?” De Strooper said.

Using Indian export-import databases, Radio-Canada followed paper shipments to see where some of the thousands of containers sent from Canada to India ended up.

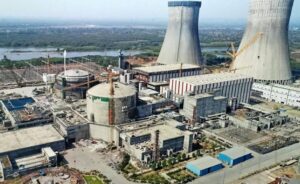

The search led the Enquête team three hours north of the capital Delhi, to the city of Muzaffarnagar. On its outskirts are 30 paper mills, many of which use subcontractors to sort plastic in the open air.

In the five sorting areas visited, the journalists found easily recognized Canadian and Quebec packaging and bags including Publi-sacs, President’s Choice, Indigo, Québon, Métro, and Cashmere toilet paper.

Mostly female, low-caste workers earning just over three dollars a day for sorting the plastic described their work.

“If you can get used to it, it’s fine,” said one of the workers. But off-camera, the sorters said the work is gruelling and the salary insufficient to support their families.

The plastic comes to them from local paper factories where it is separated and sent for further sorting. The hard plastic — drink bottles, containers and and food packages — are sent for recycling.

Local villagers say the soft plastic is burned secretly at night by the paper mills or plants that make jaggery, a form of sugar. The plastic, they say, is a much cheaper fuel source of energy than wood.

“It costs next to nothing,” said local farmer and finance worker Rahul Kumar from the nearby village of Chandpur. “One or two rupees per kilo [of plastic], while wood costs 30 to 40 rupees more.”

With a group of friends, Kumar, whose land lies close to several mills, began to identify the diseases that they suspect are linked to this pollution. They collected the medical records of people who had respiratory problems, asthma, skin diseases and cancers.

In an email, the Muzaffarnagar Pollution Control Board confirmed it has imposed fines for the illegal storage of plastic and open burning on several industries.

On the other hand, it said that only one paper manufacturer has been fined since 2019 for burning plastic. However, from official documents and media reports, Radio-Canada found at least two other instances where local officials intervened to stop paper mills from burning plastic.

At the base of a hill used by one of the paper mills to dump its ashes, Radio-Canada also found burnt plastic debris.

A 2019 report by the Center for Ganga River Basin Management and Studies cites the burning of plastic as a major malpractice in the paper industry.

Industry officials insist though that the plastic is disposed of properly.

“We give our plastic to the cement works,” said Pankajj Agarwaal, the representative of the Association of Paper Manufacturers in the region. “It is burned in good environmental conditions. It doesn’t cause any problems.”

Experts acknowledge that plastic is burned under more controlled conditions in cement plants, however the practice remains controversial due to its environmental impact.

A world away

Meanwhile, Ricova, the company that runs Montreal’s two recycling plants, says that it cannot control what happens in India. It also says that its partners treat plastic responsibly.

“The regulations are not as strong there as they are here,” says Dominic Colubriale, president of Ricova. “It may be that people may make a mess in certain places…[but] I think we do business with people who are responsible.”

“I know that part of the plastic is burned but it is done legally [and used as fuel] in cement plants,” Colubriale said.

Colubriale also says that the material he sends overseas is relatively clean and that customers tell the company there is less contamination than the city of Montreal has reported.

“I think there may be something wrong in how they are doing their evaluations,” Colubriale said of the Montreal reports.

But Montreal points out that it was Ricova that picked the firm that analyzes the quality of the materials that come out of the Saint-Michel recycling plant and evaluates the level of contamination.

A problematic sorting plant

“We know that Saint-Michel has technological challenges,” says Marie-Andrée Mauger, a Montreal borough mayor who sits on its executive committee.

The city also points out that Ricova only took possession of the old centre of Saint-Michel in 2020, when it bought the assets of the previous operator, which had gone bankrupt.

In November 2021, Ricova installed new equipment in hopes of lowering levels of contamination for mixed paper. Mauger says the city now expects better performance from the sorting centre.

But the more modern sorting centre in Lachine which opened in 2019, has a similarly high contamination rate averaging 20 per cent. Ricova attributes this poor performance to faulty sorting equipment. The company filed a lawsuit in 2021 against the manufacturer, asking for $5.5 million to buy new machinery.

Mauger also says that the city does not have any way of tracing where the paper ends up when it is sold.

She was unaware that India’s legal limit for paper contamination was two per cent and that Montreal was sending paper with over 10 times that level of contamination.

Both the federal and provincial governments say that reforms they have introduced will eventually reduce plastic consumption at the consumer level, but that won’t happen until 2025.

In the meantime Marc De Strooper continues his fight against dirty Canadian recycling.

“It breaks my heart, but all I can do is send the cargo back to Canada.”

(Gil Shochat is an award-winning investigative producer-director with CBC/Radio-Canada. Chantal Lavigne is a journalist with Radio-Canada. Courtesy: CBC News.)