We Need Festivals of Confluence, Not Orgies of Conflict

Rohit Kumar

Festivals in India have traditionally been syncretic affairs. Hindus attend Iftar parties, Muslims and Sikhs celebrate Diwali, and both Hindus and Muslims celebrate Christmas with India’s minuscule Christian community.

But a dark shadow has now fallen across this centuries-old eclecticism.

Radicalised Hindu youth who have partaken deeply of anti-Muslim propaganda over the last ten years via mainstream TV, social media, and large parts of the print media, now ‘celebrate’ festivals like Ram Navami by dancing in front of mosques to the music and lyrics of explicitly communal songs. These young people also try to plant saffron flags on those mosques and do their utmost to provoke those within. In Ratnagiri, Maharashtra on Wednesday, an attempt was made to ram the gates of a mosque.

Festivals were meant to bring about confluence. Today they are being used to foment conflict. The latest target is Holi.

Consider Bisfi-Madhubani BJP MLA, Haribhushan Thakur Bachaul’s, abhorrent ‘appeal’ to Muslims on March 10:

“I want to appeal to Muslims, there are 52 jummas (Fridays) in a year. One of them coincides with Holi. So, they should let Hindus celebrate the festival and not take offence if colours are smeared on them. If they have such a problem, they should stay indoors. This is essential for maintaining communal harmony.” (PTI)

This veiled threat has evoked a strong rebuke from Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) leader Tejashwi Yadav:

“BJP MLA (Haribhushan Thakur) Bachol has asked Muslim brothers not to come out on Holi. Who is he and how can he say such things? … This is a country that believes in ‘Ram and Rahim’. This is Bihar. He needs to understand that here five-six Hindus will protect one Muslim brother.”

Meanwhile in Sambhal, UP, Circle Officer Anuj Chaudhary has also told Sambhal’s Muslims not to step out for Friday prayers on Holi if they do not wish to get smeared by Holi colours. This, against the backdrop of not just five Muslims killed in police firing barely four months ago, but also the more recent humiliation of having to get court permission for the annual Ramzaan whitewashing of the Jama Masjid in Sambhal!

As if that were not enough, UP chief minister Adityanath has also told Muslims in UP that there is no need for them to go to the mosque on Friday the 14th as it is Holi! (He has justified Anuj Chaudhary’s belligerence by saying, “He is, after all, a wrestler and an Arjuna awardee.”)

It seems the powers that be are hell-bent on destroying all that is still syncretic and harmonious in India.

Perhaps those who want to force-fit festivals into tight religious boxes would do well to remember Aaj Rang Hai, a qawwali sung by the 13th century Sufi poet and mystic Amir, Khusrau for his spiritual master, Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya. Legend has it that Khusrau met his master on the day of Holi and wrote the qawwali in his honour.

Let that sink in. A song about Holi, a Hindu festival, composed by a Muslim Sufi poet.

Aaj rang hai hey maa, rung hai ri

Moray mehboob kay ghar rang hai ri

Sajan milaavra, sajan milaavra,

Sajan milaavra moray aangan ko

Aaj rang hai…

Mohay pir paayo Nijamudin aulia

Nijamudin aulia mohay pir payoo

Des bades mein dhoondh phiree hoon

Toraa rang man bhayo ri…

Jag ujiyaaro, jagat ujiyaaro,

Main to aiso rang aur nahin dekhi ray

Main to jab dekhun moray sung hai,

Aaj rang hai hey maa, rang hai ri.

The English translation of this qawwali by Maaz Bin Bilal reads thus:

There’s colour today, O mother, there’s a glow today,

In my beloved’s home there’s new colour today.

I’ve met my beloved, I’ve found him,

In my own yard,

It’s radiant today!

There’s colour today, O mother, there’s a glow today.

I’ve discovered my saint, Nizamuddin Aulia,

Nizamuddin Aulia, he is my saint!

I have travelled far and wide, here and abroad,

Searching,

It’s your person, your glow that’s tinged my heart.

You’ve lit up the world, the universe is lit,

Never have I seen such splendour,

Whenever I look around, he’s there with me.

There’s colour today, O mother, there’s a glow today.’

Amir Khusrau’s ‘Holi qawwali’ is an exuberant celebration of the soul finding joy, meaning and peace in union with the divine. The Sufi tradition’s emphasis on simplicity, kindness and generosity to all, regardless of religion, is echoed in Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya’s emphasis on love as a means of realising God.

For him, love for God implied love for humanity.

Perhaps if those who claim to be ‘real’ Hindus (but who spend their time vandalising mosques and persecuting Muslims) were to, by some miracle, realise that love for God is love for all humanity, they might just find the peace and satisfaction that has eluded them thus far.

(Rohit Kumar is an educator, author and independent journalist. Courtesy: The India Cable – a premium newsletter from The Wire & Galileo Ideas.)

It’s Time to Remember Gandhi’s Views on Holi and Ramzan

S.N. Sahu

Mahatma Gandhi espoused the cause of Hindu-Muslim unity till the very last breath of his life and considered it as an indispensable condition not only for attainment of independence of India but also to realise the ideal of non-violence in practice on a sustained basis.

As a necessary corollary of it, he used to flag the point that people of diverse faiths should never be deterred from celebrating their respective festivals.

It is of seminal significance to recall the enduring vision of Gandhi in the context of the aggressive calls issued in some Bharatiya Janata Party-ruled states by officials and those occupying high constitution positions asking Muslims who are fasting during the sacred month of Ramzan, to remain indoors on the occasion of Holi.

Many BJP leaders including UP chief minister Adityanath endorsed the appeal of a police official of the state that “Juma (Friday) comes 52 times a year, but Holi comes only once. Those who have a problem with the colours of Holi should stay indoors and offer their prayers there.”

This year, Holi is being celebrated on a Friday (Juma), so such appeals to Muslims to restrict themselves to their homes and covering several mosques in UP with huge sheets of tarpaulin have created an ecosystem marked by fear and intimidation of Muslims. It violates the cultural liberties of Muslims on the ground of their faith.

Gandhi on Holi

On March 28, 1938, while speaking at the Gandhi Seva Sangh meeting in Delang in Orissa (now Odisha), Mahatma Gandhi said that he would never ask Hindus to stop celebrating Holi in case a Muslim zamindar asked them to do so. Gandhi maintained that even if the celebration of Holi by Hindus would be suicidal in face of above dictats of a Muslim zamindar, they should not give up their religious practice on that account.

“I would myself,” he said, “ask the zamindar to come forward and kill me, for I would light the Holi fire right in front of him”.

“I would ask the Hindus,” he remarked, “not to break the heads of Muslims, but rather to sacrifice their own”. He proceeded to assert that nothing should be given up by getting stricken with fear and the fight based on rights would have to be launched by employing non-violent methods.

In 1938, Gandhi gave this hypothetical example to urge people to fight for their right to celebrate religious festivals. Eighty seven years later, it is not a zamindar but state functionaries who are following communally divisive policies in BJP-ruled states to segregate Muslims from Hindus on the grounds of their religious festivals, going against the constitutional vision of India.

Gandhi on Ramzan and non-violence

While addressing the Khudai Khidmatgars on October 23, 1938, Gandhi referred to the month of Ramzan that had just set in and told them how it could be used to make a start in non-violence. He said that Ramzan defined by abstention from food and drink should also be marked by shunning of anger, bitterness and acrimony to cultivate non-violence.

Ramzan was understood by Gandhi as a step towards non-violence. It is now used by BJP leaders to curb the cultural liberties of Muslims, restrict them to their homes and give primacy to Hindus.

The responsibility of the state under the Indian constitution is to treat all faiths equally and give equal opportunities to the adherents of the faiths for celebration of their festivals with dignity and poise.

Instructions of police

It is instructive that the UP police and the police of several other north Indian States have issued instructions on the occasion of the celebration of Holi. One such instruction is that all those engaged in celebrating Holi should be mindful of women’ dignity and modesty which under no circumstances should be outraged while playing with colours. In other words the police is apprehensive of the danger to women from those who taking the liberty of participating in a religious festival like Holi.

Language

Such apprehensions are evocative of what Mahatma Gandhi wrote about Holi on April 25, 1891. Writing about Indian festivals, he specifically devoted a section to Holi in an article titled ‘Some Indian Festivals III’ and wrote about the onset of spring. But he remarked sadly that language was being used during the fortnight preceding Holi. He wrote with a heavy heart, “In small villages it is difficult for ladies to appear without being bespattered with mud. They are the subject of obscene remarks. The same treatment is meted out to men without distinction. People form themselves into small parties. Then one party competes with another in using obscene language and singing obscene songs. All persons – men and children, but not women – take part in these revolting contests”.

Gandhi, however, remarked that “It is a relief to be able to say that with the progress of education and civilization such scenes are slowly, though surely, dying out. But the richer and refined classes use these holidays in a very decent way”.

Sadly 135 years after Gandhi uttered those words BJP-ruled states have slipped down the scale of education and civilisation and now Muslims are treated with contempt and hatred for observing their religious festivals. Only in the recent past they were targeted for offering Namaz in officially designated places and in some cases, even in the private spaces of their homes. Preventing them from coming out of their houses during Ramzan and hiding the mosques by covering them with thick layers of plastic just because Holi is celebrated by Hindus goes against ‘Sarva Dharma Sambhav’ – equal respect for all faiths.

In his February 29, 1920 article on Hindu-Muslim unity, Mahatma Gandhi wrote, “My dream is that a Vaishnava, with a mark on his forehead and a bead necklace, or an ash-smeared Hindu with a rudraksha necklace, ever so punctilious in his sandhya and ablutions, and a pious Muslim saying his namaz regularly can live as brothers. God willing, the dream will be realised”.

(S.N. Sahu served as Officer on Special Duty to President of India K.R. Narayanan. Courtesy: The Wire, an Indian nonprofit news and opinion website. It was founded in 2015 by Siddharth Varadarajan, Sidharth Bhatia, and M.K. Venu.)

From Mughals, Maharajas to the British – How Artists Captured Holi Celebrations

Sonal

A celebration of colour, joy and the arrival of spring, Holi long transcended its origins as a Hindu festival to become a grand celebration that found artistic expression in paintings, illustrations and manuscripts.

Vivid depictions of the festival show Mughal emperors who adopted Holi into their courtly traditions to the Rajput rulers who immortalised it in miniature paintings and British artists who documented its exuberance.

Artwork produced in the late 18th and 19th centuries capture the festival’s ability to dissolve social hierarchies and encourage uninhibited revelry.

Royal revelry

A Hindu festival marking the arrival of spring, Holi was introduced to the Mughal court as Mughal and Rajput families were tied through marriage. Holi became an integral part of imperial festivities, celebrated with music, dance and colours in the royal gardens and the zenana – the women’s quarters.

Traditionally, Holi colours were derived from natural sources, such as the bright red flowers of the tesu tree (Butea monosperma), which created a saffron hue when mixed with water. Yellow powder likely came from turmeric (Curcuma longa), while red dye may have been sourced from red sandalwood powder (Pterocarpus santalinus).

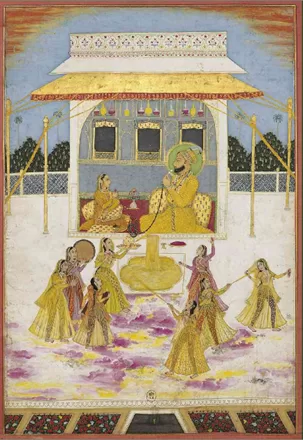

An 18th century painting in the Mughal style depicts a haloed royal smoking hukka with a woman. In front of them, eight women, adorned in rich Mughal attire, gather around a basin, splashing each other with colored water using pichkaris.

Figure 1: Prince in his zenana during Holi, 18th century.

This painting is believed to depict the eldest son of Bahadur Shah I, Sultan Muiz ud-Din in the company of his concubine and later consort, Lal Kunwar. Muizz ud-Din went on to become Mughal emperor Jahandar Shah, reigning from 1712-1713. His brief reign was marked by decadence and indulgence before his downfall and assassination.

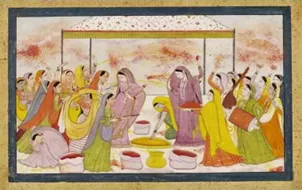

A 1780 painting from Lucknow depicts the Mughal ruler and son of Aurangzeb, Mirza Muhammad Azam Shah, at a royal Holi celebration. At the centre, Shah embraces a courtesan, surrounded by members of the zenana and women musicians. The luxurious clothing and intricate jewelry of the participants indicates their high status in the court. The ground is covered in vermillion-colored powder and water.

A calligraphic panel on the reverse is signed by Hafiz Nurullah, a scribe at the court of Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula of Awadh. This painting is linked to other works from the “Lucknow Album”, believed to have been compiled in 1785.

The painting reflects the cultural assimilation of the festival as well the artistic refinement of the Lucknow court. Similarly, a painting from 1775 depicts Asaf-ud-Daula celebrating Holi “with the ladies of his court”. This painting, too, bears a quatrain by Hafiz Nurullah.

A mid-18th century painting captures Maharaja Bakhat Singh, of the Rathore clan, engaged in Holi celebrations in a pool with a group of women of the royal court. The maharaja can be seen with a pichkari while the women throw coloured powders and water at each other.

Several women stand on the steps and balconies – some carrying pichkaris, some holding plates with colored powder while a group plays music. This Rajput miniature painting is characterised by its vibrant colours, intricate detailing and architectural precision.

A watercolour from 1765 depicts a maharaja playing Holi with women and musicians in a garden pavilion. The painting is likely from Karnataka and was featured in an exhibition of miniatures from the Mughal and Deccani Schools.

Mughal aristocrats like Prince Azim ush Shan, the grandson of Aurangzeb, celebrated Holi in Dacca – modern-day Dhaka. Nawazish Muhammad Khan, another Mughal aristocrat, once celebrated Holi for seven days at the Motijheel Palace in Murshidabad. Like the Mughals, the nawabs of Bengal, too, embraced Holi celebrations during the 18th century, notes Historian Sushil Chaudhury.

In 1757, Nawab Siraj-ud-Daula joined Holi festivities after signing the Treaty of Alinagar with Robert Clive of the East India Company. As the East India Company took control of Bengal in the latter half of the 18th century, official holidays for Holi were five-seven days.

Bhakti touch

The Rajput-style paintings that depict deities Krishna, Radha and the gopis playing Holi are unparalleled in their details and aesthetic production.

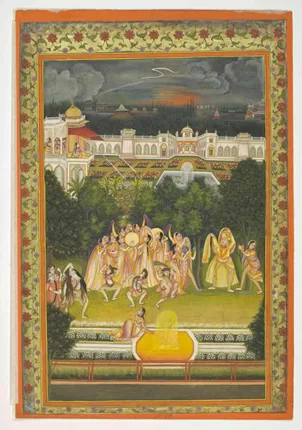

A 1788 painting from Kangra shows women throwing red and orange powders and spraying colored liquid at one another.

Radha, the beloved consort of Krishna in Hindu mythology, is the central figure on the left.

Figure: Radha celebrating Holi, c 1788, Kangra, India.

An anonymous painting from around 1790, in the Mughal style, shows Krishna playing Holi with the Gopis. This painting blends illusion and reality as the princess on a balcony envisions Krishna and the gopis playing Holi in a forest grove, covered in pink and yellow dye. The women of the zenana watch from above as the scene unfolds below.

Among the revelers, are yogis clad in animal skins alongside a dancing hijra – “khawaja sara”, a member of a traditional transfeminine third gender in Persian – joyfully waving her shawl.

Figure: “Radha and Krishna celebrate Holi”, c 1760-1780.

Bazaar scenes and ‘Hohlee’

The celebrations of ordinary Indians also found vibrant artistic representation.

A Murshidabad painting from 1785 depicts a vibrant celebration outdoors: Men, covered in red powder, dance, sing, and play drums as they make their way toward a tank. At the centre, a man is carried on a litter while bystanders observe the festivities.

This artwork is part of a series of nine drawings that illustrate a durbar at the Murshidabad court, along with various Hindu and Muslim festivals and religious ceremonies.

English artist William Carpenter, in a watercolour from 1850, depicts the Sadr Bazaar of Pune, where three young children stand in front of a market stall, curiously inspecting flowers and coloured powder on display.

Of the many depictions of Holi during the colonial period one stands out for not just its aesthetics, but also the accompanying literature.

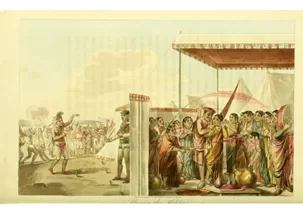

The illustration “Playing the Hohlee”, etched by T Baxter and drawn originally by Deen Alee, was included in a book by English writer and soldier Thomas Duer Broughton. This Company-style painting depicts a group of women under a canopy holding plates or baskets of coloured powder. A man, possibly Daulat Rao Scindia of the Gwalior Kingdom, puts colour on one of the women. There are also large pots of coloured water, into which a woman can be seen dipping her pichkari in.

Figure: “Playing the Hohlee”

Broughton, in his book Letters Written In A Mahratta Camp, an account of his travels through 1809 gave a vivid account of life in India while he journeyed through Rajasthan alongside Scindia and his army. In this book he describes “Hohlee” as a Hindu Carnival and a time of “universal merriment and joy” observed by all classes: “Playing Hohlee consists in throwing about a quantity of flour, made from a water-nut, called singara, and dyed with red sanders: it is called abeer; and the principal sport is to cast it into the eyes, mouth and nose of the players, and to splash them all over with water, tinged with an orange colour with the flowers of the dak tree.”

His description of Holi celebrations under a large canopy at Scindia’s camp is especially vivid. Broughton writes of the tent erupting in celebration as the maharaja and his officials lead the celebrations and participants pelt each other with powder and water. The maharaja, he writes, is shielded by attendants and retaliates with a fire-engine hose, drenching everyone.

Broughton observed that beyond royal festivities, Holi was marked by street celebrations. Men paraded through towns and camps, singing “kuveers” with bawdy humor, mocking superiors. Some dressed in grotesque costumes as personifications of Holi, while others delighted in shouting coarse jokes at women. At women-only gatherings there were dances through the night.

The festival lasts through Phagoon, or Phalgun, the last month of the Hindu year that ends with the burning of Holika.

Broughton notes that the term “Phagoon” originates from two Sanskrit words – Phal, meaning “faults” or “slight errors”, and Goon, meaning “admissible” or “venial”. It implies that minor social transgressions, such as playful teasing, indecent jokes and lighthearted mischief are permissible during this season, as even nature seems to indulge in excess and when the songs are marked with more than ordinary licence, they are termed Dhumaree.

He noted that the officers who participated in the celebrations earned greater affection from their men, who delighted in playfully including their names in Holi songs – the more indecent the lyrics, the louder the laughter and applause.

But not all Holi songs are “indelicate”, he says, offering a translation of one about Krishna being chased by a party of gopis during Holi:

While some his loosened turban seize,

And ask for Phag, and laughing tease;

Others approach with roguish leer,

And softly whisper in his ear.

With many a scoff, and many a taunt,

The Phagoon some fair Gopees chaunt ;

While others, as he bends his way,

Sing at their doors Dhumaree gay.

One boldly strikes a loving slap;

One brings the powder in her lap;

And clouds of crimson dust arise

About the youth with lotus-eyes.

Then all the colour’d water pour,

And whelm him in a saffron shower;

And crowding round him bid him stand,

With wands of flowers in every hand.

Artwork over the centuries not only documents the cultural assimilation of Holi across regions but also highlight the festival’s role in fostering artistic expression and social harmony. Together, these artworks serve as a tribute to the syncretism of the festival of colours.

(Sonal is Assistant Professor of History at Motilal Nehru College, University of Delhi. She specialises in the history of colonial India. Courtesy: Scroll.in, an Indian digital news publication, whose English edition is edited by Naresh Fernandes.)