“I do not want my house to be walled in on all sides and my windows to be stuffed. I want the culture of all lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible. But I refuse to be blown off my feet by any.”

∼ M.K. Gandhi

On the eve of Mahatma Gandhi’s 150th birth anniversary, Union home minister Amit Shah made a provocative statement about ensuring that no Hindu, Buddhist, Sikh or Jain refugee would be refused entry into India; earlier, RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat said no Hindu would be turned out of India even if their name were not listed in the National Register of Citizens.

The pointed exclusion of Muslims in Shah’s statement is hardly surprising, since that has been the objective of his ideology and organisation. What is different is that the dog whistling of the past, when leaders in constitutional positions only beamed out such messages during campaign time. Now, the second most important minister in the cabinet minces no words in saying that Muslims are unwelcome in this country.

For those who will point out the irony of Shah’s remarks on Gandhi Jayanti, which commemorates a man who was committed to inclusiveness and proactively reached out to Muslims, here’s a suggestion – don’t waste your time. India is well into the post-irony period and those in power are hardly concerned with how they are perceived by liberals, “sickulars” and plain decent citizens. Indeed, Narendra Modi may be extra sensitive to editorials in the foreign media or the approval of international leaders, but Shah couldn’t care two hoots.

Modi has appropriated Gandhi, even if only cherry picking his message on cleanliness and making him the mascot of the Swachh Bharat campaign. Late last month, while on his trip to the United States, he released a Gandhi stamp and spoke about the Mahatma at the United Nations.

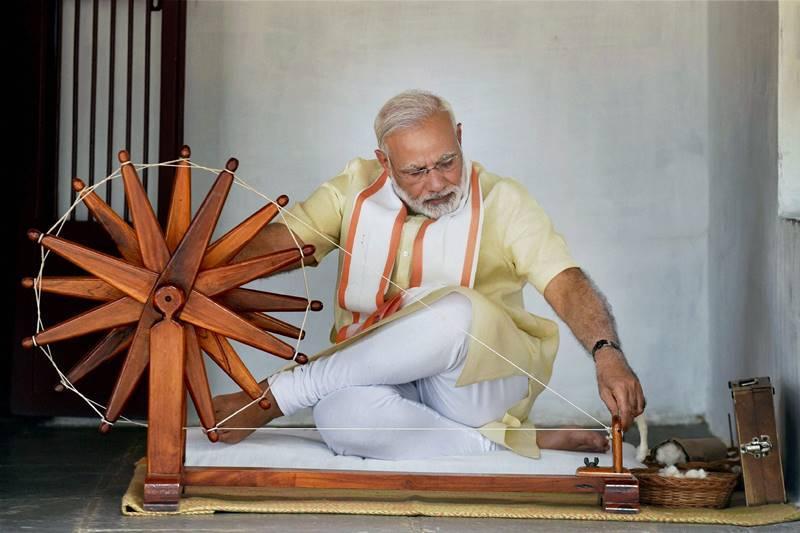

A photograph of Modi spinning the charkha was used in a calendar of the Khadi and Village Industries Commission in 2017 and he has laid flowers at Gandhi’s statues abroad.

He may not have been particularly pleased doing this – the RSS, where he received his formative training, blamed Gandhi for Partition – but Modi knows the value of Gandhi the brand. Not only is it recognised everywhere in the country but also internationally; associating with it can only enhance the Modi brand. This may be an extremely cynical, even hypocritical on the part of Modi, but there is another way of looking at it: the very fact that he understands the importance of appropriating Gandhi in modern India is an acknowledgement that the Mahatma is not to be wished away. That is why Modi has written a oped in New York Times and RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat has written a piece for Hindustan Times on Gandhi and his message.

Modi may admire V.D. Savarkar, who too was accused in Gandhi’s assassination, but knows that while the Sanghis may worship him, the world remains ignorant and unimpressed by ‘Veer’s’ alleged achievements. No country is rushing to install a bust of Savarkar, no one is issuing stamps of Gandhi’s enemies or assassins. It may yet happen in the future, as Modi’s government continues its drive to eliminate great historical figures and replace them with their own heroes. But so far, it is Gandhi whom the world knows and respects.

He was assassinated all those years ago and today he is being continuously undermined and re-examined. The Right wing hates him and the Left has many problems with him. African historians have pointed to his racism during his stay in South Africa. For the record, many South African descendants of the Tamil- and Telugu-speaking indentured labourers in the country are not as enamoured of him as the Gujaratis are. Many of his ideas are problematic – the over-romanticisation of the village economy, the paternalistic view of caste and much more, but Gandhi rises above it all. If anything, he would have welcomed scrutiny of his ideas and utterances, welcoming his detractors to debate and discussion. He was not mean-minded and petty and it is this quality of his that stands out most of all in our times, when resentment and spite seem to dominate the polity.

To see BJP leaders – including an MP, Pragya Thakur – hail Nathuram Godse is to understand how much India has changed. Modi said he wouldn’t be able to forgive her for the remark and disciplinary action was promised by the party, but the reality is that no action followed. Even so, the fact that the BJP felt compelled to make these pro-forma noises shows that there are lines – as yet – that it will not be able to cross, not publicly anyway. In private, the Sanghis make their antipathy to Gandhi known quite vigorously, but even they have to maintain some public decorum.

All this points to a fundamental truth – goodness and noble deeds and ideas cannot be wished away. Flawed and problematic he may be but Gandhi still remains with us all these decades later. The world, from Martin Luther King to protestors in Hong Kong, revered him and draws inspiration from him. His brutal killing has not dented his fame and popularity and never will. His killers will never become heroes, no matter what their fans think.

Even today, with all the power and resources at its command, the Sangh parivar finds it difficult to scrub his legacy from the Indian mind. History books can be rewritten, films can be made and loose cannon leaders can be allowed to make anti-Gandhi statements which they then withdraw. Reducing him to just a cleanliness icon, without focusing on his ideas about social harmony, is one way of belittling him. But their efforts will come to naught. In the end, the forces of darkness will dissipate, forgotten and unmourned, but Gandhi will go on forever.

(Sidharth Bhatia is a journalist and writer based in Mumbai and is a Founding Editor of The Wire. Article courtesy: The Wire.)