Twenty-first-century capitalist production can no longer be understood as a mere aggregation of national economies, to be analysed simply in terms of the gross national products (GDPs) of the separate economies and the trade and capital exchanges occurring between them. Rather, it is increasingly organised in global commodity chains (also known as global supply chains or global value chains), governed by multinational corporations straddling the planet, in which production is fragmented into numerous links, each representing the transfer of economic value. With more than 80 percent of world trade controlled by multinationals, the annual sales of which now equal around half of global GDP, these commodity chains can be seen as fastened at the center of the world economy, connecting production, located primarily in the global South, to final consumption and the financial coffers of monopolistic multinational firms, located primarily in the global North.

The commodity chain of General Motors includes twenty thousand businesses worldwide, mostly in the form of parts suppliers. No US automobile manufacturer imports less than around 20 percent of its parts from abroad for any of its vehicles, with imported parts sometimes amounting to around 50 percent or more of the assembled vehicle. Likewise, Boeing purchases from abroad about a third of the parts it uses for its aircraft. Other US companies, such as Nike and Apple, offshore their production to subcontractors, mainly in the periphery, with production carried out according to their exact, digital specifications—a phenomenon known as arm’s length contracting, or what is sometimes referred to as non-equity modes of production. This offshoring of production by today’s multinational corporations in the center of the world economy has led to a vast shift in the predominant location of industrial employment, from the global North up through the 1970s to the global South this century.

Studies have found that the accelerating pace of offshoring is closely related to foreign direct investment (FDI) in low-wage areas in the periphery, associated with intrafirm trade. In 2013, the global FDI inflows to “developing economies” reached a record high of 52 percent of total FDI, exceeding flows to developed economies for the first time ever, by $142 billion. But of equal importance today is arm’s length contracting. The World Bank indicates that 57 percent of all US trade is arm’s length trade, while a rapidly growing part of this is taking the form of monopolistic arm’s length contracting, involving specified production carried out by subcontracting firms (such as the Taiwanese Foxconn operating in China) producing commodities (such as iPhones) for buyer-driven multinational corporations (such as Apple). In general, the lower the per-capita income of a US trading partner, the higher the share of US arm’s length trade, indicating that this is all about low wages. Even multinationals with high levels of FDI are heavily involved in arm’s length trade, moving in this way between direct and indirect exploitation. Arm’s length contracts generated about $2 trillion in sales in 2010, much of it in developing countries. In 2010–14, the world economy grew at a 4.4 percent rate while arm’s length trading grew at a 6.6 percent rate, far exceeding the former.

Although these phenomena are not entirely new, the scale and sophistication of commodity chains today represent qualitative changes that are transforming the character of the entire global political economy. Twenty-first-century imperialism therefore cannot be studied, as in earlier periods, mainly on the level of the nation-state, without a systematic investigation of the increasing global reach of multinational corporations or the role of the global labour arbitrage, sometimes referred to in business circles as low-cost country sourcing. At issue is the way in which today’s global monopolies in the center of the world economy have captured value generated by labour in the periphery within a process of unequal exchange, thus getting more labour in exchange for less. The result has been to change the global structure of industrial production while maintaining and often intensifying the global structure of exploitation and value transfer.

The complexity of the world employment situation generated by global commodity or supply chains is indicated in Table 1, which includes the countries with the largest shares of employment in global commodity chains in 2008 and/or 2013.

Table 1. Countries with the Highest Proportion of Global Supply Chain Jobs (GSC Jobs), and their Primary Export Destination

| 2008 | 2013 | |||

| Country | Share of all GSC jobs | Primary Export Destination | Share of all GSC jobs | Primary Export Destination |

| China | 43.4% | United States | 39.2% | United States |

| India | 15.8% | United States | 16.8% | United States |

| Indonesia | 4.6% | Japan | 4.6% | China |

| Russian Federation | 4.1% | Germany | 4.1% | China |

| Brazil | 3.5% | United States | 4.1% | China |

| Germany | 3.4% | France | 3.6% | China |

| United States | 3.3% | Canada | 3.6% | China |

| Japan | 2.3% | United States | 1.9% | China |

| Mexico | 1.8% | United States | 2.2% | United States |

| South Korea | 1.7% | United States | 2.1% | China |

| United Kingdom | 1.7% | United States | 1.9% | United States |

| Total | 85.6% | 84.2% |

As Table 1 shows, China and India provide by far the largest share of the total employment engaged in global commodity chains, while, for both countries, the United States is the primary export destination. This creates a situation where production and consumption in the world economy are increasingly severed from each other. Moreover, value added, associated with such commodity chains, as we shall see, is disproportionately attributed to economic activities in the wealthier countries at the center of the system, although the bulk of the labour occurs in the poorer nations of the periphery or the global South.

In this article, we seek to understand how the new imperialism of the global labour arbitrage works and how value, derived from low-wage labour in the periphery, is being captured globally. Utilising a publicly available database of world economic activity, we construct a series on unit labour costs incorporating both labour productivity and wage levels.

Examination of unit labour costs of key countries in both the center and the periphery of the world economy demonstrates that, in twenty-first-century imperialism, multinational corporations are able to carry out a process of unequal exchange in which they get, in effect, more labour for less, while the excess surplus obtained is often misleadingly attributed to innovative, financial, and value-extractive economic activities taking place at the center of the system. Indeed, much of the immense value capture associated with the global labour arbitrage circumvents production in the center economies, at the expense of workers there who have seen their jobs offshored. This has contributed to the amassing of vast pyramids of wealth disconnected from economic growth in the center economies themselves. Much of this draining of value from the periphery takes the form of unrecorded illicit flows. According to one recent pioneering study of global financial flows by the Centre for Applied Economics of the Norwegian School of Economics and the United States-based Global Financial Integrity, net resource transfers from developing and emerging economies to rich countries were estimated at $2 trillion in 2012 alone.

Huge quantities of this loot captured from peripheral economies in the global South ends up being parked in the “treasure islands” of the Caribbean where trillions of dollars of money capital are now deposited, outside of the tax and accounting apparatuses of even the most powerful nation-states.

What is clear is that the globalisation of production is built around a vast chasm in unit labour costs between center and periphery economies, reflecting much higher rates of exploitation in the periphery. This reflects the fact that the difference in wages is greater than the difference in productivity between the global North and the global South. Our data shows that the gap in unit labour costs in manufacturing between key core (United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and Japan) and key periphery emerging states (China, India, Indonesia, and Mexico) has been on the order of 40–60 percent during most of the last three decades. This enormous gulf between global North and global South arises from a system that allows for the free international mobility of capital, while tightly restricting the international mobility of labour. The result is to hold wages down in the periphery and to make possible the enormous siphoning off of economic surplus from the countries of the South.

Global Commodity Chains and Imperialist Value Capture

The term supply chain is often used to refer to “a sequence of production operations,” which begins at conception and development of the product or system, goes through the production process including acquisition of inputs (raw materials, tools, equipment), and finishes with distribution, maintenance and consumption.

Global commodity chains are integrated global spaces created by financial groups with manufacturing activities. Such spaces are integrated in that they are made up of hundreds, even thousands, of subsidiaries (production, R&D [research and development], finance, etc.) whose activities are coordinated and controlled by a central body (the parent company or a holding company) that manages resources to ensure that the whole process is profitable both financially and economically.

The participation of countries in such global commodity chains has a profound impact on labour. This can be seen from the rapid increase in the number of jobs related to global commodity chains, from 296 million workers in 1995 to 453 million in 2013. This growth in commodity-chain production is concentrated in “emerging economies” where such job growth reached an estimated 116 million from 1995 to 2013, with manufacturing as the predominant sector and directed at exporting to the global North. In 2010, 79 percent of the world’s industrial workers lived in the global South, compared to 34 percent in 1950 and 53 percent in 1980. Manufacturing has become the chief source of the third world’s dynamism both in exports and in production, especially in East and Southeast Asia, where, by 1990, the manufacturing share of GDP was higher than that of other regions. A report by the Asian Development Bank shows that most countries in Southeast Asia, particularly those that are considered developing, experienced an increase in their manufacturing output shares from the 1970s to the 2000s.

The key driver in this ‘new wave’ of globalisation is a new corporate strategy. The strategy involves a search for lower costs and greater flexibility, as well as a desire to allocate more resources to financial activity and short-run shareholder value while reducing commitments to long term employment and job security. Major multinational corporations today do not manufacture their own products. They have become large retailers and branded marketers, and they are the new drivers in the global chains that have become more prominent over the last couple of decades. Arm’s length production by multinational corporations—of which Nike and Apple are perhaps the best-known examples—is associated with governance structures in which corporations, usually situated at the center of the world economy, play a pivotal role in setting up dispersed production networks in exporting countries, typically in the third world. They are actually not real manufacturers, but merely merchandisers, that is, companies that ‘design and/or market, but do not make, the branded products they sell.’

Economists often highlight arm’s length corporate contracting as a new decentralised system of production. But there is actually no decentralisation; the ‘dispersed’ commodity chains associated with a given multinational with no equity in the various production segments that it has subcontracted out are crucially governed by its centralised financial headquarters. The financial headquarters of a multinational retains monopolies over information technology and markets, and appropriates the larger portion of the value added in each link in the chain. Despite China’s reputation as the largest exporter of high-technology goods, economist Martin Hart-Landsberg points out that 85 percent of the country’s high-technology exports are mere links or nodes in the global commodity chains of multinationals. As Hymer said a few decades ago: the headquarters of multinationals “rule from the tops of skyscrapers; on a clear day, they can almost see the world.”

Arm’s length contracts actually allow firms to capture extremely high profit margins through their international operations and exert strategic control over their supply lines—regardless of their relative lack of actual FDI. But this is profit flow is difficult to identify, as there are no visible flows of profits from these foreign subcontractors to their global North customers—multinationals. Thus, not a single cent of H&M’s, Apple’s or General Motors’ profits can be traced back to the super-exploited Bangladeshi, Chinese and Mexican workers who toil for these MNCs’ independent suppliers, and it is this “arm’s length” relationship which increasingly prevails in the global value chains that connect MNCs and citizens in imperialist countries to the low-wage workers who produce more and more of their intermediate inputs and consumption goods.

However, a closer look at the logic behind these forms of offshoring will allow us to see the labour-value commodity chains and power relations embedded in them. The question is not merely about how the multinationals govern commodity chains, but also how they facilitate the extraction of surplus from the global South. This is captured in the concept of the global labour arbitrage, defined as the replacement of high-wage workers in the United States and other rich economies with like-quality, low-wage workers abroad—taking advantage of the difference in wages—based on the unequal freedom of movement of capital and labour. Although labour is still largely constrained within national borders due to immigration policies, global capital and commodities have far more freedom to move around, further heightened in recent years due to trade liberalisation. The global labour arbitrage thus serves as a means for multinationals to benefit from the enormous international differences in the price of labour.

The global labour arbitrage is thus the overexploitation of labour in the global South by international capital. It extracts more out of workers through various means, including repressive work environments in periphery-economy factories, state-enforced bans on unionisation, and quota systems or piece-rate work. It constitutes unequal exchange, understood as the exchange of more labour for less, in which monopoly-finance capital at the center of the system benefits from high markups on low-cost labour in the global South. The process of unequal exchange at the same time marks the further incorporation of the global South countries into the global economy.

The global labour arbitrage is made possible in part by what Marx refers to as the industrial reserve army of the unemployed—which in this case is on a global scale, thus a global reserve army of labour. The creation over the last few decades of a much larger global reserve army is partly connected to the “great doubling” phenomenon, which refers to the integration of the workforce of former socialist countries (including China) and formerly heavily protectionist countries (such as India) into the global economy, with the resulting expansion of the size of both the global labour force and its reserve army. Also central to the creation of this reserve army is the depeasantisation of a large portion of the global periphery through the spread of agribusiness. This forced movement of peasants from the land has resulted in the growth of urban slum populations.

Making use of the global reserve army of labour not only serves to increase shorter-term profits; it serves as a divide-and-rule approach to labour on a global scale in the interest of long-term accumulation by multinationals and the state structures aligned with them. Although competition among corporations is limited to oligopolistic rivalry, competition among workers of the world (especially those in the global South) is greatly intensified by increasing the relative surplus population. This divide-and-rule strategy serves to integrate disparate labour surpluses, ensuring a constant and growing supply of recruits to the global reserve army who are made less recalcitrant by insecure employment and the continual threat of unemployment.

It follows from the above discussion that the freely competitive model has been made obsolete. Nevertheless, the “traditional” rule of fighting for low-cost production is still alive and well. Indeed, one may argue that it is intensified in the age of monopoly-finance capital. The goal of multinationals is always the creation and the perpetuation of monopoly power and monopoly rents, that is, the power to generate persistent, high economic profits through a mark-up on prime production costs. As production becomes globalised, the leading oligopolies in the Triad of the United States and Canada, Europe, and Japan compete to reduce labour and raw materials costs. They export capital to the underdeveloped countries in order to secure a high return on the exploitation of abundant cheap labour and the control of economically pivotal natural resources.

Estimating the Value Captured by MNCs through Global Labour Arbitrage

To get an idea about the value captured by MNCs from labour in the global South through offshoring practices, we make a comparison of national differences in unit labour cost—a measurement of the labour cost to produce one unit of a product. Unit labour cost is a composite measure, combining data on labour productivity and wages to assess the price competitiveness of a given set of countries. It is typically presented as the average cost of labour per unit of real output, or the ratio of total hourly compensation to output per hour worked (labour productivity). We are interested in determining how changes in unit labour costs over time relate to countries’ participation in global commodity chains, and how this relationship can help explain the extraction of surplus from the global South.

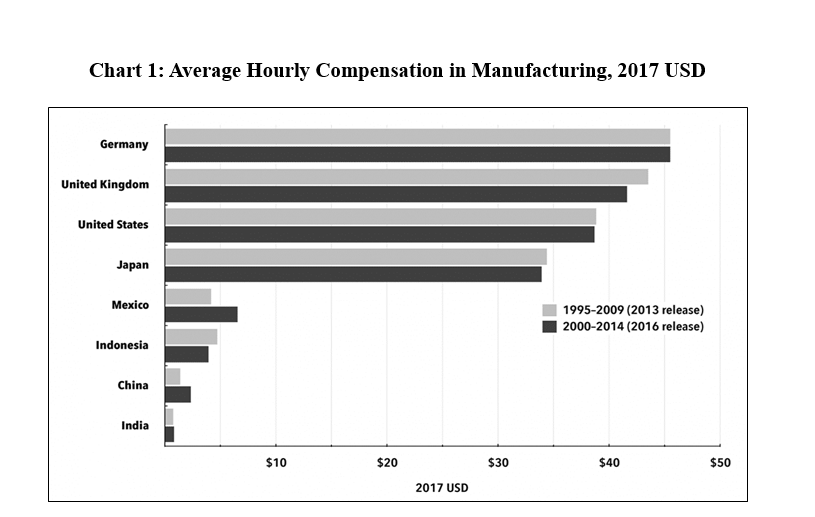

For this, it is useful to look first at a comparison of hourly compensation in dollar terms, which points to the vast discrepancies in wage levels internationally between the global North and the global South.

Chart 1, which reports average hourly labour compensation in manufacturing industries in 2017 US dollars, illustrates the wage chasm that exists between economies of the global North and global South. The data show that there is a massive discrepancy in wage levels between center (global North) and periphery (global South). Here, hourly compensation is converted into actual dollars.

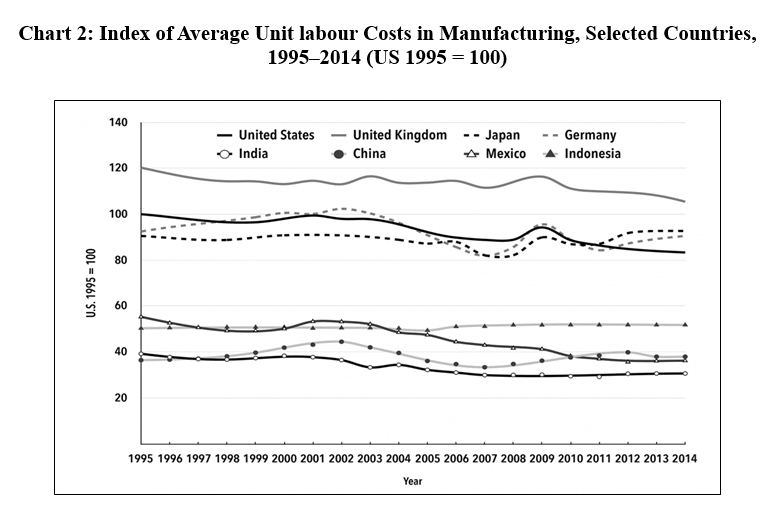

Chart 2 presents an index of unit labour costs in a number of key core developed and periphery emerging countries accounting for significant shares of global supply chain jobs in the global economy between 1995 and 2014—a period stretching from the development of the high-tech bubble of the 1990s to the Great Financial Crisis of 2007–09 to the early years of recovery from the crisis. The chart shows the huge gap that exists between unit labour costs in manufacturing in the advanced industrial economies in the global North and the emerging economies in the global South. The four advanced industrial economies (United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and Japan) are fairly tightly clustered together, while all four have much higher unit labour costs than the four emerging economies (China, India, Indonesia, and Mexico).

It is obvious that other factors besides unit labour costs, such as infrastructure, taxes, primary export country, shipping costs, and finance affect location of critical nodes in commodity chains. Nevertheless, with China’s unit labour costs rising relative to the United States and India’s remaining flat, it is hardly surprising that Apple through its Foxconn subcontractor has recently decided to assemble its top-end iPhones as well as cheaper models in India beginning this year. While in 2009 Apple’s gross profit margins on its iPhones assembled in China were 64 percent, rising unit labour costs have clearly cut into these margins.

The conclusion that much higher profit margins can be obtained through outsourcing production to poorer, emerging economies—when compared to profit margins to be obtained through labour in the wealthy economies at the center—is inescapable. All four of the global South countries depicted in this study (China, India, Indonesia, and Mexico) have seen generally flat or declining unit labour costs relative to the United States.

Altogether, the above data shows clearly why it has been so beneficial—indeed, necessary from the standpoint of profitability—for economies of the global North to maintain substantial parts of their labour-value commodity chains in poor emerging economies. By means of these commodity chains, corporations in the North are able to secure low-cost positions essential to their global competitiveness, based on much higher rates of labour exploitation. Here it is important to underscore that a given product, such as an iPod or an iPhone, often has its parts manufactured in a number of different countries, for example, Germany, Korea, and Taiwan, but the assembly occurs in China—a country that has among the lowest unit labour costs and offers developed infrastructure, scale effects, etc.—so it is marked as made in China. In other words, while the commodity chain is complex and extended, the country with the lowest unit labour costs tends to be the site of final production/assembly and becomes the most critical node for the enlargement of gross profit margins.

The way in which the labour-value commodity chains work at the ground level is best illustrated by looking at a particular example, like the Apple iPhone hitherto manufactured in China, which has become the global assembly center for much of modern manufacturing. Most production for export via multinational corporations in China is assembly work, with Chinese factories relying heavily on cheap migrant labour from the countryside to assemble products. The main technological components of this final assembly are manufactured elsewhere and then imported into China. Apple subcontracts the production of the component parts of its iPhones to a number of countries, with Foxconn subcontracting the final assembly in China. Due in large part to low-end wages paid for labour-intensive assembly operations, Apple’s gross profit margin on its iPhone 4 in 2010 was found to be 59 percent of the final sales price. The share of the final sales price actually going to labour in mainland China itself was only a fraction of the whole. For each iPhone 4 imported to the United States from China in 2010, retailing at $549, only about $10, or 1.8 percent of the final sales price, went to labour costs for production of components and assembly in China.

Similar conditions of globalised exploitation pertain to other countries, particularly where multinational corporations rely on subcontractors (or arm’s length production). In the international garment industry, in which production now takes place almost exclusively in the global South, direct labour cost per garment is typically around 1–3 percent of the final retail price, according to senior World Bank economist Zahid Hussain.

In 1996, a year for which data on the labour-value component of Nike’s commodity chain for its shoes is available, a single Nike shoe consisting of fifty-two components was manufactured in five different countries. The entire direct labour cost for the production of a pair of Nike basketball shoes in Vietnam in the late 1990s, retailing for $149.50 in the United States, was $1.50, or 1 percent.

A 2019 study published by the Blum Center for Developing Economies at the University of California, which interviewed 1,452 Indian women and girls (including children 17 years old or younger)—85 percent of whom did home-based work “bound for export to major brands in the United States and the European Union”—determined that these workers earn as little as fifteen cents per hour. They “consist almost entirely” of female workers from “historically oppressed ethnic communities” in India, and their work typically involves “finishing touches” like embroidery and beadwork.

These extremely exploitative economic relations help us understand the reality of labour-value commodity chains and how they relate to the global labour arbitrage. In essence, each node or link within a labour-value chain represents a point of profitability. In effect, labour values generated by production are “captured” and not registered as arising in the peripheral countries due to asymmetries in power relations, in which multinational corporations are the key conduits.

Hidden in the pricing and international exchange processes of the global capitalist economy is an enormous gross markup on labour costs (rate of surplus value) amounting to superexploitation, both in the relative sense of above-average rates of exploitation and also, frequently, in the absolute sense of workers paid less than the cost of the reproduction of their labour power. So extreme is this overaccumulation that the twenty-six wealthiest individuals in the world, most of whom are Americans, now own as much wealth as the bottom half of the world’s population, 3.8 billion people. Structurally, this level of inequality has become possible as a result of a globalised commodity-chain system of exploitation—a new imperialist division of labour associated with global monopoly-finance capital.

The world capitalist economy, judged in terms of the amassing of financial wealth and asset concentration, is becoming in many ways more centralised and hierarchical than ever. What we are seeing is the emergence of a global wealth pyramid in which the fabled wealth hierarchy of the pharaohs pales into insignificance in comparison. Inequality is increasing in almost all nations as well as between the richest and poorest countries. As Oxfam indicates, the issue before us is the question of “an economy for the 99%.” In the meantime, imperialism continues to cast its long shadow over the global economy.

(Intan Suwandi has written for various publications on the political economy of imperialism. R. Jamil Jonna is associate editor for communications and production at Monthly Review, the renowned American socialist magazine.)