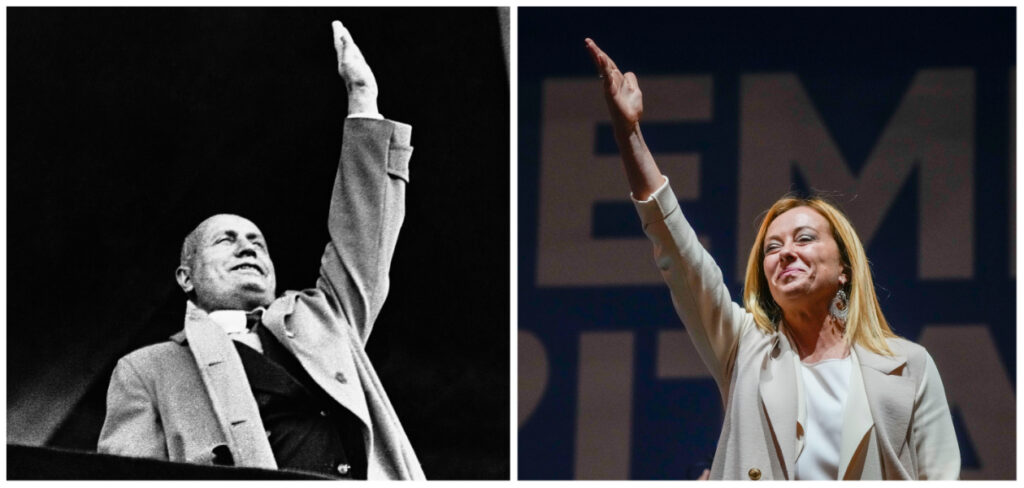

In the recently held elections in Italy, a hard-right coalition led by Giorgia Meloni of the Brothers Of Italy party gained a convincing majority in the country’s Parliament. This takeover of power by a group described by many analysts as “neo-fascists” had been accurately predicted by the polls, but it still sent a seismic wave coursing through Europe. The rise of the far right in Italy is a development shared by a large number of European countries, a continent wide socio-political dilemma, and not simply a challenge for a single country (Pianta, 2020). The emergence of ultra conservative populist parties across the continent has rightly been linked to the popular frustration arising out of the unfulfilled promise of globalization, accompanied invariably by a decline in support for mainstream left parties (Milner, 2021). Examples of conservative right wing movements – some of which even captured power – can be found, for instance, in East-Central Europe (Schering, 2021). Over the years, nationalistic parties have also gained prominence in the largest European economies such as France and Germany.

Contextualising the rise of the right in Italy

The rise of the far right in Italy, and elsewhere in Europe needs to be understood in the context of the failure of the left parties and movements to further the interests of the working class as well as those on the margins of the society in their politics as well as policy frameworks. It’s a failing, which is even more palpable in case of the central or “technocratic” governments, which were in power for almost a decade. To quote philosopher Santiago Zabala (2022), “moderate governments, parties and coalitions in the centre are not taking into consideration the real needs of the people while forming their policies. Most European citizens want clear, direct policies that can solve their economic problems.” In my opinion, this holds true for Italy, too.

In 2013, Tito Boeri, an influential Italian economist, had proffered the idea that Italy needed a ‘middleman’ to lead the country out of the recession – ‘a person with an untarnished reputation; someone people would trust’ (Boeri, 2013). Mario Monti and Mario Draghi, the leaders of the technocratic government seemed not to have met those expectations, and the Italian voters’ lingering sense of disillusionment may have nudged them in the direction of authoritarian politicians. Today, that search is more easily met by right-wing coalitions rather than by the political left, and Giorgia Meloni’s charismatic leadership propelled by her considerable communications skills has moved an ultra conservative and authoritarian platform to the centre stage in Italy (Giubilei, 2020).

The economic challenges faced by the Italian working class

The academic discussion on the current Italian economic impasse is quite varied – the failure of the liberalization framework to kick in reforms (e.g. Boeri and Garibaldi, 2011), the inability (or even the unwillingness) of the welfare state to promote social investments as well as secure reforms in the Italian labour market (Kazepov and Ranci, 2020) or inefficient institutional changes, which unnecessarily meddled with existing institutional complementarities and provisions for social support without providing any improvements in return (e.g. Simoni, 2020). Irrespective of the accuracy of these explanations, the fact remains that it is the marginalized working classes, which have always faced the brunt of these failures, while the enduring inflationary pressures on the economy have further exacerbated that situation. In addition, persistent political instability in Italy continued to prevent any possibility of designing long-term strategies for establishing genuine green economic programs promoting ecological sustainability and economic equality in the country.

Today, according to official statistics, Italy is experiencing unprecedented levels of poverty. In 2021, for instance, 1.9 million households (7.5% of the total) and about 5.6 million individuals (9.4% of the total) lived in absolute poverty (ISTAT, 2022). Furthermore, Italy has one of the highest debt-to-GDP ratio in the Eurozone, a direct result, according to many analysts, of the ineffective policies adopted by successive left-wing ruling coalitions, which have left the weaker sections quite unprotected. Consequently, the Italian left has endured a steadily shriveling trust deficit among the electorate (Triglia, 2021). Similarly, owing to their inept response to the financial crisis of 2012, the European Union and its various satellite institutions also failed to regain trust in Italy (Perissich, 2019). In the aftermath of the downturn, it became increasingly evident that Italian citizens, in their search for domestic solutions to country-specific problems, had begun looking at the programs of nationalistic and populist parties with distinct interest. And, these explorations gained momentum when the Covid pandemic further exacerbated the characteristic shortcomings of the Italian political, administrative and institutional system (Vicentini and Galanti, 2021). Analysts believe that these circumstances may have pushed the Italian working class to look for an authoritarian political leader like Meloni to help solve their everyday economic challenges.

Could the non-traditional left play a role in addressing the ecological and economic crisis?

While left and progressive ideas have always been a part of the larger policy debate and electoral tussle in Italy, environmental issues have mostly stayed on the fringe of that political process. The main reason for that has been the inability of the political parties to organize citizens’ discontent on issues like climate stresses, industrial pollution, ecological imbalances, and push it effectively into the country’s political arena. The Italian Five Star Movement (Movimento Cinque Stelle), which created quite a stir in Italian politics soon after its founding in 2009, is a case in point. The party emerged as an alternative to the “old politics” of pragmatic short-term coalition governments, and with a professed intention of designing a long-term people-focused policy framework for the country (Passarelli and Tuorto, 2018). The popular perception of being a party with a difference enabled Five Star Movement to mobilize a substantial section of the population to support its political platform, allowing it to lead a government from 2018 until 2021 (Ignazi, 2021).

The enduring complications of Italian politics intervened soon after the elections in 2018, when Five Star Movement realized it couldn’t form a government on its own, and had to look for a coalition partner. As it started working on a common platform with Matteo Salvini’s right wing League, its 52-page declaration on the environment was whittled down to three pages by the end of the six weeks of negotiations. The ministry of environment’s budget, which had been cut in half in the ten years between 2008 and 2018, from € 1.65 billion to € 880 million, was further slashed in 2019. The Movement had promised that it would turn a polluted steel factory in southern Italy into a renewable energy park, instead it allowed the plant to be taken over by the steel giant ArcelorMittal. Finally, as no progress had been made on the environment front, the European Environment Agency accorded Italy the dubious distinction of having the largest number of inhabitants living in areas where pollution levels exceeded the EU pollution limits. (1)

The normalization process, which followed Five Star Movement’s success led it to slowly abandon its original purpose, and embrace many of the ideological features attributed to the ‘new politics’ of the libertarian left as well as the ‘new populism’ of the radical right (Pirro, 2018), but without developing the kind of alternatives that it had promised to deliver. In the last few years, it has become quite clear that Italian political parties – whether on the left or the right of the political spectrum – are unable to figure out a way to protect the environment and biodiversity while at the same time preventing an economic and social crisis. It took a substantial amount of time for a new vision for environmental protection in Italy to be formalized and institutionalized in the constitution (Corvino and Stefancic, 2022), yet there is no movement or party, which is willing to initiate rigorous debate on the need for integrating ecology into the political process. Italian Green Party, for instance, has been struggling since the mid-1990s (see Rhodes, 1995) and is barely noticeable in current politics. It seems Italy will continue to miss out on a serious ecological debate in the foreseeable future now that a far right coalition with no expressed interest in that subject is about to take over power in Rome.

Exploring “alternative” economic initiatives in Italy

Given the persistently stressful economic situation in the country and the continual failure of the Italian political system to address it, are there any avenues available for communities to exercise their own agency to intervene in the situation? Some experiments are taking shape in Italy, and perhaps mark the beginning of a rethink on the relationship of local communities to their own immediate economies, and even on how businesses should be conducted.

In 2020, in the wake of the Covid induced socio-economic turmoil in the country, a small town in southern Italy, Castellino del Biferno, started issuing its own currency, the Ducati, to support the local economy (2). It was calibrated to the Euro, and the town council distributed the bank notes to the 550 residents according to their economic needs. In a smart utilization of the 5,500 euros they received from the government to issue food stamps, the council added its own savings to the kitty to bolster the faltering local economy. A similar experiment had taken place in another southern town, Gioiosa in 2016 where a local currency was issued and accepted at the local stores (3). The town attracted a large group of asylum seekers in that period, and to integrate them into the local economy the town council issued what they called a “ticket” to support the local businesses. This strategy also helped diffuse any potential tension between locals and the newcomers, a socio-economic policy success achieved through the exploration of alternatives.

Another remarkable, new social phenomenon shaking up the traditional notions of business, and even property in Italy is that of the “sharing economy”. Structured around the principles of cooperation, collaboration and the allocation of a resource, good or service without gaining its property, the sharing economy initiative in Italy began utilizing web tools to open up new possibilities in car share, co-working, renting and selling in the secondary goods market, micro lending, Fab Lab workshops (open to the public, and offering tools and services for small scale digital manufacturing) and other open source digital platforms. The sharing economy is eroding the boundaries between producers and consumers, and people are establishing their own operative links for creating, sharing, buying and selling of goods and services, all based on the specifics of their money flow and orders – no faceless markets dictate the terms on these business interactions. (4)

Analysts have suggested that significant potential exists for synergy between Italy’s emerging “sharing economy” sector and the enormously dynamic world of traditional cooperatives, but, a cultural barrier prevents that possibility from being realized. The entrenched practitioners of traditional cooperativism in Italy are skeptical of the virtual world, and see it as encroaching upon the real world, which is well established, and has been a sturdy provider of job security and income for a large number of people for a long time. They view any intrusion as possibly destabilizing, and the enormous presence of cooperatives in Italian life makes that a valid concern – for instance, the consumer cooperative, Coop with a 20 percent market share is the largest retail chain in the country. What is even more interesting is that the owners of the business are its 7.4 million consumers spread across the country. (5) Even though Coop occupies a place within the larger free market arena, the ownership of a portion of the cooperative’s operations allows for imagining alternatives to the contemporary model of corporate ownership. The popularity of the cooperatives model is even more pronounced in the Emilia Romagna region of northern Italy – two out of every three people, there are members of a cooperative, and an impressive 30% of the region’s GDP emerges from that work (see for instance Ecchia and Mazzanti, 2016; Caselli et al. 2021).

One of the reasons why the cooperative sector in Italy has been able to survive the mismanagement of the economy by its elite is the direct access it has to funding sources – crowd funding through its membership, which has allowed it to survive stressful periods earlier. But, it is doubtful whether the current inflationary and other pressures on the economy would allow for the continuation of such public funding as the average consumer is forced to tighten her purse. Some analysts have, however, pointed out that the sharing economy and cooperation on digital platforms could address that issue by harnessing their facility for creating direct links between producers and consumers. An emergence of synergy between the old and new forms of cooperation may create an “alternative future” for Italy.

Resistance and “alternative” futures

While “alternatives” could contribute to addressing the current economic hardships faced by the Italian people, what about the expected extreme rhetoric, repression and, perhaps, violence that ultra right ascent could lead to and has accompanied such political takeovers elsewhere in Europe and in other parts of the world? Do “alternatives” have the political acumen and the social networking needed to face that impending onslaught? One model of possible replication and a definite sources of inspiration is the cooperative movement – during the fascist period a large segment of the Italian cooperatives faced up to the regime’s repression as well as its attempt at coopting their operative structure into the fascist fold, not always successfully but certainly with definite purpose and organization. As right wing politics unfolds in Italy, the ideological orientation of some of the leading cooperatives would give hope to the marginalized sections of society – immigrants, LGBT, feminists and the poorest of the poor – currently being targeted by the lumpen elements within the ultra-right formations. For instance, Legacoop, the largest cooperative in the country has deep progressive roots and has traditionally aligned itself with movements and public opinion trying to protect the pluralist social framework of Italy.

Arguably, resistance to the ultra-right has already begun in Italy. A nationwide protest by economic and environmental justice groups, labor unions and women’s rights activists has been planned for November 5th, and is expected to attract a huge number of protesters all over the country.(6) And, in keeping with the Italian tradition of sprouting new parties periodically, activists are also working toward the formation of a political party, which could advocate and fight for social and environmental justice. As these new attempts for political mobilization start crystalizing, it would be imperative for the “alternatives” practitioners and thinkers to align themselves with these initiatives and co-create the future that Italy needs, now.

Notes

1. https://www.thelocal.it/20190228/italy-five-star-movement-environment-pollution/

2. https://cointelegraph.com/news/italian-town-creates-new-currency-to-cope-with-covid-19

3. https://cointelegraph.com/news/italian-town-creates-new-currency-to-cope-with-covid-19

4. https://global.ilmanifesto.it/sharing-economy-small-digital-platforms-grow-in-italy/

5. https://www.yesmagazine.org/economy/2016/07/05/the-italian-place-where-co-ops-drive-the-economy-and-most-people-are-members

6. https://inequality.org/great-divide/in-italy-a-setback-for-a-more-equal-future/

References

Benasaglio Berlucchi, A. (2021) ‘Understanding the populism of the Five Star Movement – and its continuity with the past’, blogs.lse.ac.uk, 26 August

Boeri, T. and Garibaldi, P. (2011) Le riforme a costo zero: Dieci proposte per tornare a crescere. Milan: Chiarelettere

Boeri, T. (2013) ‘Desperately seeking a middleman’, Contemporary Italian Politics, 5(2): 222-228

Caselli, G., Costa, M. and Delbono F. (2021) ‘What do cooperative firms maximize, if at all? Evidence from Emilia‐Romagna in the pre‐Covid decade’, Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics (2021).

Corvino, F. and Stefancic, M. (2022) ‘Is Italy’s new vision for environmental protection a real commitment to carbon neutrality?’, radicalecologicaldemocracy.org, 3 April

Ecchia, G. and Mazzanti G. M. (2016) ‘Case study on Social Innovation in Emilia Romagna’, Social Innovation Community

Giubilei, F. (2020) Giorgia Meloni: La rivoluzione dei conservatori. Rome: Giubilei-Regnani

Ignazi, P. (2021). The failure of mainstream parties and the impact of new challenger parties in France, Italy and Spain, Italian Political Science Review/Rivista Italiana Di Scienza Politica, 51(1): 100-116

ISTAT – Italian National Institute of Statistics (2022) Poverty in Italy: Year 2021 (Report), 7 July

Kazepov, Y. and Ranci, C. (2017) ‘Is every country fit for social investment? Italy as an adverse case’, Journal of European Social Policy, 27(1): 90-104

Milner, H. V. (2021) ‘Voting for populism in Europe: Globalization, technological change, and the extreme right’. Comparative Political Studies, 54(13): 2286-2320

Passarelli, G. and Tuorto, D. (2018) ‘The Five Star Movement: Purely a matter of protest? The rise of a new party between political discontent and reasoned voting’, Party Politics, 24(2): 129-140

Rhodes, M. (1995) ‘The Italian Greens: struggling for survival’. Environmental Politics, 4(2): 305-312.

Schering G. (2021) The Socio-Economics of Illiberalism: Culture and Economy are Not Alternative Explanations, sase.org/blog 17 June.

Simoni, M. (2020) Institutional Roots of Economic Decline:Lessons from Italy, Italian Political Science Review/Revista Italiana Di Scienza Politica, 50(3): 382-397.

Perissich, R. (2019) Stare in Europa: Sogno, incubo e realtà. Torino: Bollati Borringhieri.

Pianta, M. (2020) Italy’s Political Upheaval and the Consequences of Inequality, Intereconomics, 55: 13-17

Pianta, M. (2021) Italy’s Political Turmoil and Mario Draghi’s European Challenges, Intereconomics, 56(2): 82-85

Pirro, A. L. (2018) ‘The polyvalent populism of the 5 Star Movement’, Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 26(4), 443-458

Trigilia, C. (2021) ‘Il grande esodo. Perché le classi deboli si stanno allontanando dai partiti di sinistra?’, il Mulino, 70(1): 26-37

Vicentini, G. and Galanti, M. T. (2021) ‘Italy, the sick man of Europe: Policy response, experts and public opinion in the first phase of Covid-19’. South European Society and Politics, 1-27

Zabala, S. (2022) The EU is to blame for the rise of the far right in Europe, Aljazeera.com, 28 April

(Mitja Stefancic is co-editor of the “World Economics Association- Commentaries”. He works in the fields of political and social economy with expertise and deep interest in the cooperative movement. Courtesy: Radical Ecological Democracy. The Radical Ecological Democracy platform and web journal are the initiatives of the India based Kalpavriksh Environmental Action Group, which has been in the forefront of the struggle for environmental sanity and sustainability in India for the last four decades.)