“Words cannot be found to relate what happened; it was too terrible.” This is how Jan Kubas, an eyewitness of the events that followed the battle of Ohamakari in what was then called German South West Africa, now Namibia, in 1904, articulated his struggle to express his memories of the German pursuit of the Ovaherero into the parched Omaheke desert. Kubas was a member of the racially-mixed Griqua people who lived at Grootfontein near the area where following the extermination order by German general Lothar von Trotha, thousands were driven into the barren Omaheke.

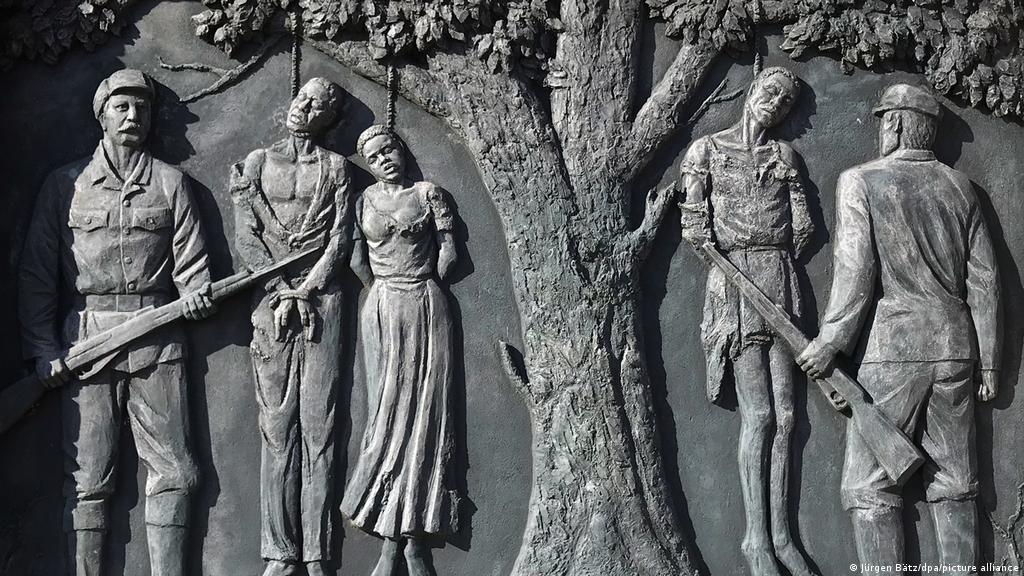

In 1904 and 1905 the Ovaherero and Nama people of central and southern Namibia rose up against colonial rule and dispossession. The revolt was brutally crushed. By 1908, 80% of the Ovaherero and 50% of the Nama had succumbed to starvation and thirst, overwork and exposure to harsh climates. Thousands perished in the desert; many more died in the German concentration camps in places such as Windhoek, Swakopmund, and Shark Island.

A century after Jan Kubas struggled to articulate the horrors he witnessed in 1904, the German government has, at long last, officially acknowledged the colonial genocide. An agreement between the German and Namibian governments was recently concluded. According to the agreement, German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier will soon travel to Windhoek and offer a formal apology for the first genocide of the 20th century; the deal also stipulates additional German development aid for Namibia. These funds, to the amount of 1.3 Billion Euro, will be paid over the next thirty years. They will be earmarked for special “reconciliation and reconstruction” projects to benefit the Ovaherero and Nama communities that were directly affected by the genocide.

There are many open questions, however: What are possible international ramifications of the Namibian-German agreement? Will the deal possibly turn the tide more broadly for reparation claims from ex-colonies of the empires of European colonialism?

Penetrating questions need to be asked also about the extent to which Germany is committed to “working through” its violent colonial past. Has it, following decades of avoidance, truly committed to addressing its painful colonial past? Can the restitution of looted cultural objects and human remains from the postcolonial metropole’s museums and academic collections be considered a serious and sufficient effort at decolonization? What are the limitations of recent challenges to the historical staging of former colonial empires in the public space, such as monuments, and the renaming of streets, which were named after colonial despots?

And in national as well as transnational perspectives: What could be the next steps in going beyond dealing with the colonial past in purely symbolic terms? What kind of new solidarities are being forged in moves towards decolonization, racial justice and re-distribution?

Reactions

When the announcement that after almost six years of bi-lateral negotiations an agreement had been initialled by the Namibian envoy, Zedekia Ngavirue, and his German counterpart, Ruprecht Polenz, the German government and mainstream media celebrated this as a political and moral triumph: “Germany recognises Genocide” broadcast the main news bulletin of the state television ARD on 28 May 2021. The deal was quickly dubbed the “reconciliation agreement” in German discourse. The leader of the German delegation, Polenz remarked confidently that with the promise of special aid Germany would ensure that the acknowledgment and apology did not remain lip service.

The Namibian government’s announcement was much more subdued. President Hage Geingob’s spokesperson cautiously expressed that the agreement was a “first step in the right direction”. However, associations of the affected communities, the Ovaherero and Nama, whose ancestors had been victims of the genocide, were a whole lot more critical. They criticized the agreement on substantial as well as procedural grounds: For one, the German government had succeeded to enforce its stated principle not to pay reparations for the crimes committed during German colonial rule. And, as they had done for years, descendants of the victims protested that they had not been properly involved in the process. Ovaherero traditional leader Vekuii Rukoro, who sadly succumbed on the 18 June to the terrible Covid surge currently haunting Namibia, called the agreement “an insult“; a statement, which made front page headline news on the The Namibian newspaper.

Members of the victim associations took to the streets of Windhoek. Even those representatives of the affected communities, who had in the past been more amenable to the negotiation process, expressed their concerns in growing numbers. They particularly questioned the amount of the payment package, which was far lower than what had been expected by the Namibian government, who had rejected, in 2020, the earlier German offer of 10 million Euro compensation. While the amount offered now is an improvement on last year’s, it still falls short of Namibian expectations, as even Namibian Vice-President Nangolo Mbumba admitted although he officially accepted the German offer on behalf of his government.

For Namibians, and the descendants of the genocide victims in particular, it is not all about the amount of money though. Activist and politician Esther Muinjangue, the former Chairperson of the Ovaherero Genocide Foundation, now an opposition MP, and also Namibia’s Deputy Minister of Health and Social Services, cut to the chase when she unequivocally stated that “development aid can never replace reparations”.

The Namibian government’s official response on 4 June 2021 clearly attempted some damage control and referred to the agreed “reconstruction and reconciliation” payments as a “reparations package”. This is in distinct contradiction to the official language of the agreement that these payments were decidedly not reparations but an additional set of development aid. Three weeks after the announcement of the agreement, and what the German government had obviously hoped would bring closure to a painful past, there’s only one phrase to describe the situation: it’s a total mess.

Reparations

When former German Foreign Minister Joseph ‘Joschka’ Fischer visited Windhoek in October 2003 he went on record to say that there would be no apology that might give grounds for reparations for the genocide, which was committed by German colonial troops in Namibia. Fischer’s rather undiplomatic words are indicative of the intense and heated, historical and present relations that are at stake.

There is an underlying conjecture of the German-Namibian negotiations: what are the potential international ramifications of accepting legal, political and moral responsibility of reparations for colonial violence and genocide. Colonial Germany may have committed genocide, according to the UN definition, “with intent to destroy, …, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group” only in Namibia; but it certainly carried out atrocities and mass killings also in other colonial territories. Esther Muinjangue nailed it when she said: “We know that the German Government is guilty equally when it comes to the people of Tanzania or when it comes to the people of Cameroon. So, they want to safeguard themselves.” The German government fears more claims from ex-colonies; it also fears claims from European countries such as Greece, which have never received compensation for World War Two war crimes.

Then there are the shared postcolonial anxieties among the former colonial empires. Would Germany’s acceptance of its colonial past open the floodgates to a surge of claims by formerly colonized nations, in Africa as elsewhere, against their erstwhile colonizers? Muinjangue thinks this a likelihood: “all countries that were present at the Berlin Conference of 1884 and divided up the African continent are guilty: France, Britain, Belgium, and many others. They all have blood on their hands – and they all fear that one day they will have to pay reparations for their crimes.” The fears of former empires, such as Britain, France and Belgium, have been the proverbial elephant in the room.

Not without us…

If any agreement between a former colonizing power and the formerly colonized should stand a chance of bringing about justice and reconciliation, the descendants of those affected must be closely listened to. This means that they should be appropriately included in the negotiations. This has been the vocal persistent demand of genocide victim groups for an inclusive process under the slogan “not without us” ever since the negotiations between Namibia and Germany began in 2015. In January 2017 representatives of Ovaherero and Nama traditional authorities filed a lawsuit in New York, which although ultimately unsuccessful, sent a strong message to Germany and the Namibian government that negotiations “without us” remained unacceptable for those whose ancestors were killed in the genocide.

A common grievance, often expressed in Namibia, questions Germany’s pronounced difference of responding to different victims of genocide. Ever since 1990, descendants of those who suffered under the colonial genocide have often asked me, why did Germany pay generous and easily negotiated reparations to Israel after the reparations programme, which was created when Konrad Adenauer, the first chancellor of West Germany and Israel signed the Luxembourg Agreement in 1952, but has been so recalcitrant regarding Namibians? Why did the German government readily include the Jewish Claims Conference as representatives of Jewish non-governmental organisations but insisted on government-to-government only talks with Namibia? Is it “because we are Africans”, with these words Namibians regularly express suspected racism.

Restitutions: Symbolic reparations, not quite…

Symbolic commemorations of Germany’s African genocide have taken place over the past few years. If not without controversy, human remains of genocide victims were repatriated from Germany to Namibia in 2011, 2014 and 2018. These had been shipped to academic and medical institutions in Germany, and had remained there until recently.

In 2019 some significant items of cultural memory, which had been stolen during colonial conquest, were returned to Namibia from the Linden Museum in Stuttgart. These included the slain Nama leader Hendrik Witbooi’s Bible and his riding whip.

Other former German colonies have also begun to claim restitution. In 2018 Tanzania’s ambassador to Berlin requested the repatriation of human remains, which are being stored in German museums and academic institutions. In Berlin alone the remains of 250 individuals were identified, and more are suspected to be in Bremen, Leipzig, Dresden, Freiburg, and Göttingen. Provenance research on the human remains from former German East Africa also include about 900 remains of colonized people from Rwanda, which together with today’s Tanzania and Burundi formed colonial German East Africa. Also, in 2018, the President of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation promised funding for future provenance research in transnational collaborations on collections of human remains with the perspective of repatriation to Cameroon, Togo and Papua New Guinea.

Yet, the debacle of the Namibian-German “reconciliation” agreement points out that the attempts at addressing the German colonial past, including, but not restricted to the shared-divided history of Germany and Namibia, have thus far been at best half-hearted.

Bronzes, a boat & street names

At the same moment that the “reconciliation agreement” was presented in Germany with some fanfare, controversy erupted once again around the Humboldt-Forum. Berlin’s ambitious new museum is housed in the royal Prussian palace in central Berlin; the reconstructed Baroque structure that was built over the past decade at a cost of over 680 Million Euro. In this space in the historical centre of imperial Germany, controversially, ethnographic collections will be exhibited. The Humboldt-Forum has been at the centre of highly critical responses from anti-colonial and black community civil society organisations, cultural workers, as well as historians and anthropologists. Its claim to decolonization has been highly contradictory.

Just before news broke about the Namibian-German agreement, high-profile German politicians loudly congratulated each other for their decision to return some of the hundreds of Benin bronzes kept in German museum collections to Nigeria. Until recently Benin bronzes were meant to occupy pride of place in the new museum in central Berlin, where Germany wants to demonstrates its cosmopolitanism; now German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas celebrated the “turning point in our way of dealing with [our] colonial history”. Quite ironically, just a week later the next prominent scandal of colonial loot hit the news. A new book by the historian Götz Aly revealed the dark history of an artistically stunning vessel looted from former German-New Guinea in 1903.

Berlin’s leading museum officials displayed an astonishing level of ignorance. Even more astounding was the suggestion to continue exhibiting the beautifully decorated 16 metres long boat, that was built by residents of Luf Island in the Western part of the Hermit Group, and who fell victim to German colonial atrocities in the new museum by declaring it “a memorial to the horrors of the German colonial past”. This arrogance is indeed astounding since there is still no memorial in Berlin to honour the victims of German colonialism and genocide in the central Berlin space, near the Reichstag, where Germany honours the Jewish victims of the Holocaust, and belatedly, now also the victims of the Porajmos (genocide of the Roma and Sinti), and the Nazis’ persecution of homosexuals.

A tongue-in-cheek suggestion came from a leading historian of German colonialism and genocide. In a column in die tageszeitung Jürgen Zimmerer, Professor of Global History at Hamburg University, asked why not turn the reconstructed Prussian Palace itself into a fitting memorial. His proposition: fill-up its centre courtyard with sand from the Omaheke desert, or break up the castle’s fake Baroque façade with barbed wire in remembrance of the concentration camps in colonial Namibia.

Then there is street renaming, the most noticeable form of postcolonial activism in the German public space. A well-known dispute over street names comes from Berlin’s Afrikanisches Viertel (‘African Quarter’), where from 2004 civil society activist groups have been calling for the renaming of streets, which are currently named after German colonial despots. The members of the long-standing activist group Berlin Postkolonial and other initiatives, now active in cities and towns across Germany, have employed decolonial guided walking tours as a main tool of intervention. Recently, one of Berlin’s oldest campaigns gained success when the former Wissmannstrasse in the borough of Neukölln was renamed Lucy-Lameck-Strasse. The infamous German colonial officer and administrator was thus supplanted with the Tanzanian liberation fighter and politician, who after her country’s independence campaigned for gender justice.

Entangled memory: from violent pasts to new solidarities

The question remains, how much real change can come from the symbolic engagement with the colonial past. A future-oriented trajectory will point out that, beyond symbolic action, Germany’s culture of remembrance has to face challenges for the country to understand its own history within European colonialism.

Public debates in Germany have frequently posited colonialism and Holocaust memory against each other; it is alleged that an expansion of “working through the past” to include the colonial era, would ‘relativize’ the Holocaust. In contrast to this supposed competition of memory, Michael Rothberg’s concept of Multidirectional Memory has recently garnered some interesting, though at times controversial attention in public debate. Rothberg’s intervention, translated into German only twelve years after the original publication of the book in 2009, has become a catalyst for productive dialogues. In a nutshell, Rothberg suggests that memory works productively through negotiation and cross-referencing with the result of more, not less memory.

Berlin-based Ovaherero activist Israel Kaunatjike

An interesting case to explore new ways of thinking about colonial memory, social change and solidarities relates to the historical legacies of racial science and eugenics, which were developed by the anthropologist Eugen Fischer on the basis of research in Namibia in 1908. Fischer’s research was mainly used in the European colonial empires. From 1927 it was further developed under his leadership at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity and Eugenics (KWI-A) in Berlin-Dahlem. From 1933 it became the basis of the Nazi race laws that targeted Jews and other racially and socially ‘undesirables’. Today the colonial roots of racism and inequality, as well as the systematization of racial studies and eugenics in Nazi Germany, continue to raise questions about the politics of remembrance and decolonization.

During excavations on the grounds of the Free University, which now occupies the site of the former KWI-A, hastily buried human remains were discovered. In 2015 and 2016 the University commissioned archaeological expertise on these finds. The KWI-A entertained close connections to the Auschwitz camp. Thus the initial suspicion was that the excavated bones may have belonged to people murdered during the Nazi era. However, when the archaeological report was presented during a well-attended online meeting in February 2021, it turned out that the situation was more complex. Some of the remains seem to have originated indeed in crimes against humanity that were perpetrated during the Nazi terror. Others, however, are more likely to originate in anthropological collections from the colonial era. It appeared impossible to ascertain the regional origins of the remains of the about 250 individuals. This gave rise to new solidarities that originated in entangled forms of remembering the atrocities of the colonial and Nazi eras. Representatives of Jewish, Black, and Sinti and Roma communities now work together to ensure that these human remains are treated with dignity.

Such new forms of solidarity are already practiced in civil society and transnationally in the global anti-racist movement. When the global Black Lives Matter movement formed a year ago, young activists got involved in Germany as well as in Namibia. In Windhoek, the movement was directed primarily against the statue of the German colonial officer and alleged city founder Curt von François. Not only the Nama and Ovaherero communities, but also young Namibians from all sections of the population are confronting colonial legacies. Over the past year the young Namibian activists who campaigned against the offensive monument and who support the claims of the descendants of the genocide survivors, have clinched a number of social justice issues as part of their decolonizing activism, and have been calling for an end to sexism, patriarchy, and racism.

In Germany too, civil society activists have played a big role and the “reconciliation agreement” is owed, more than anything else, to their post-colonial remembrance work. Campaigning started around 2004, i.e., the time of the centenary of the genocide. In October 2016, for instance, an international civil society congress, “Restorative Justice after Genocide”, brought together over 50 Herero and Nama delegates and German solidarity activists in Berlin. The participants staged public protests and Ovaherero and Nama delegates held a press conference in the German Bundestag. And now that the, unsatisfactory, agreement is on the table, activists in Germany are again campaigning vibrantly in solidarity with the affected Namibian communities and have taken to the streets of Berlin. The current Namibia solidarity alliance brings together civil society outlets of long-standing, and young groups, who have come together during the past year’s surge of radical anti-racist activism.

The agreement that has been concluded falls short of expectations in many ways. However, it can be an impetus for the former colonial rulers and the formerly colonized to finally begin a meaningful conversation about the difficult divided history. The question arises as to whether the civil society decolonization movements in both Germany and Namibia can influence the future politics of remembrance in both their countries in a way that makes a solidarity-based post-colonial policy of reconciliation and justice possible.

(Heike Becker focuses on the politics of memory, popular culture, digital media and social movements of resistance in southern Africa (South Africa and Namibia). She also works on decolonize memory activism and anti-racist politics in Germany and the UK. Courtesy: Review of African Political Economy Journal.)