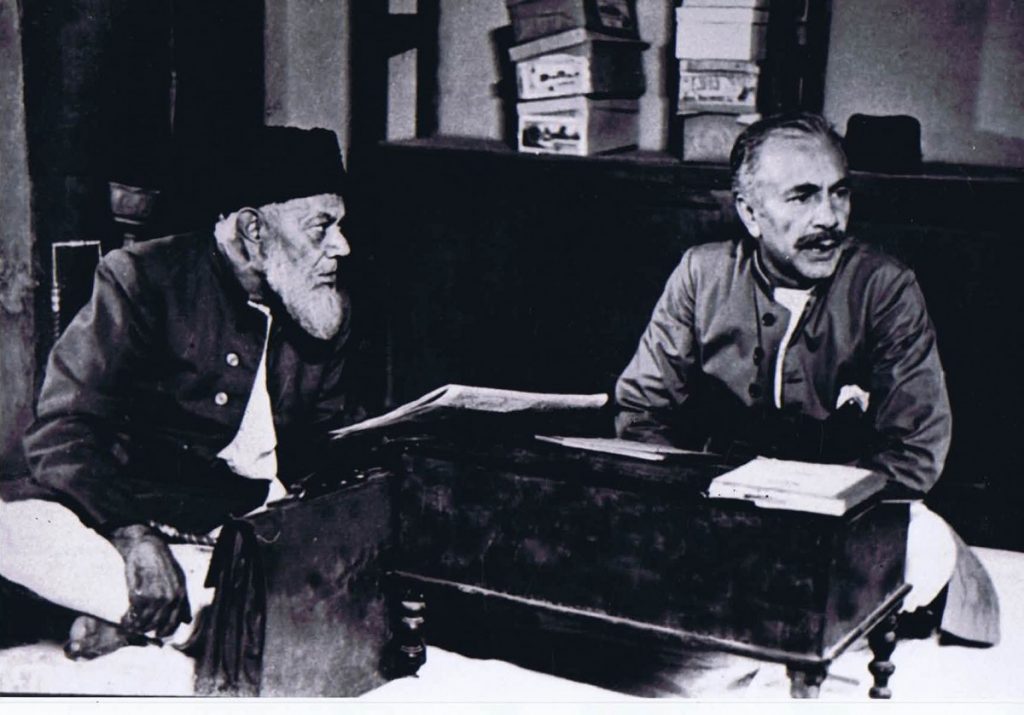

Sidharth Bhatia interviews M.S. Sathyu

[In 1974, the film Garm Hava was released and won accolades not only in India but also abroad. It was a small budget film part-funded by the government’s Film Finance Corporation. A searing look at how the Partition broke up many Muslim families – it has left a lasting impact on Indian cinema.

Starring stalwarts like Balraj Sahni, Shaukat Azmi, Farooq Shaikh, Jalal Agha, Gita Siddharth, it tells the story of the Mirza family of Agra which is divided on the issue of moving to the newly formed country of Pakistan. The script was written by Shama Zaidi and Kaifi Azmi. It is now considered the best ever film on the Partition. Garm Hava was the first film made by M.S. Sathyu and won the national award. Sathyu received the Padma Shri in 1975.

On July 6, 2020, he spoke to The Wire‘s Sidharth Bhatia about his early career as an art director and how Garm Hava came to be made in a video interview. The following is a transcript of the interview, edited lightly for clarity and style.]

Sidharth Bhatia: Sathyu sahab, welcome to The Wire. And warm wishes on your 90th birthday.

M.S. Sathyu: Thank you.

SB: Obviously, there are a lot of fans out there of your films and your masterpiece Garm Hava. So we thought it would be a good opportunity to talk to you about your career, about that film and about what’s going on in the country; what was going on then. People are not very aware of your career before that, but you were a stalwart in theatre. You were an assistant director, you were an art director and you won a Filmfare Award. So, tell us about the early parts of your career from the 1950s.

MS: Well, I started my career in Bombay, although I was studying in Bangalore before that. I left my studies and went to Bombay in 1952 looking for an opportunity to work in films. For nearly four years, I was unable to get any proper job anywhere in any of the film industry outlets.

Then waited and did theatre work to an extent. I worked with various theatre people. I had a problem with language because I didn’t speak any of the local languages of Bombay like Marathi, Gujarati or Hindi. I only knew Kannada and English and a bit of Tamil, which is spoken in my home. It was a bit of a problem at the time and I didn’t know how to utilise my time in the theatre. So, I concentrated basically on the technical aspects of theatre. I started working backstage and doing lighting, makeup and designing. That’s how I started, and slowly I learnt the local languages. I then shifted my activity.

I worked with the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) for quite a long time and directed plays. I was unable to get an opening in films but later on, it just happened that Chetan Anand came to know about me and he was making a film called Anjali on 2500 years of the Buddha. It was about Anand, a disciple of Buddha, on whose life the film was being made. [Chetan Anand] called me over and asked me to work as an assistant director.

Back then, I did not know what an assistant director’s job is. I said, “Why don’t you just make me a designer? I would rather design the sets and the costumes for a period film like this.” But he said no, he had an art director. So he said, “Don’t worry about anything. If you know anything that’s good enough. You can read the script, it will be in English. You’ll work as an assistant.” And he himself was acting in the film in the main lead. As an assistant director for the first time, I started calling the shots. That is very strange, very few get an opportunity to do that.

SB: I wanted to just go back a bit. What was the atmosphere in IPTA like in the early 1950s? We had just achieved independence and it was quite at its peak in those days, if I recall.

MS: The activity was very less in the IPTA. They take hardly six months to do a play and things like that. Very few shows were being done. So, we started reviving the whole thing. Earlier it was very active. The Bombay group was one of the most active theatre groups but there was a lack of leadership, there was a lack of activity and almost nothing was happening really. For a theatre, the most important thing is to always be in contact with the audience. It’s very important to build an audience and have a regular number of shows and things like that. That was not happening. Later on, after Ghalib’s centenary, we did a play called Aakhri Shama. That revived IPTA, in a way. We opened the play in Delhi at the Red Fort. Diwan-i-Aam (Red Fort) was the place chosen to do the play. It was kind of a mushaira (poetry symposium) of that period. It was after nearly a hundred years that the whole mushaira was enacted with Ghalib as the central figure. That brought back activity regularly and then a lot of shows took place, all over the country. Then the other plays started happening.

SB: And it was full of stalwarts, wasn’t it? I mean, famous people who became really famous later on.

MS: Yeah, there were a lot of people who were very well known like K.A. Abbas, Habib Tanvir, Kaifi Azmi, Vishwamitra Adil and Dina Pathak. There were a lot of people but the tug as a group had broken down. Some of them had left later. People like Utpal Dutt started their own theatre, Sombhu Mitra started his own Bohurupee and Dina Pathak started her own theatre in Ahmedabad. So there was a lot of split amongst the “leaders” of that period. But, I won’t say it was a breakdown of any kind. I thought the same activity multiplied. They started doing it under different banners. You see the thing is, for a theatre person, somewhere or the other his name becomes important. But IPTA had this slogan. It didn’t give credit to the individual – they were only an ensemble. The credit was to the people working for IPTA. So, there was no individual recognition and that’s how people started leaving IPTA and going away.

SB: So, again Chetan sahab made Anjali which I remember reading somewhere was not that much of a commercial hit?

MS: Yeah, you see, Chetan sahab was not totally a commercial filmmaker. He had made films like Neecha Nagar for that. He was a person who knew theatre and he started a kind of middle path, I should say. Neither commercial nor too intellectual. He had started a new kind of theatre – more realistic in approach.

In 1962, when the Chinese aggression took place, we were all very angry. Almost the entire country was angry with China and Zhou Enlai. Chetan Anand came to Delhi and he met me – I was working in a newspaper office which was publishing Link and the Patriot – a tabloid. I was working there. And then he said, he is making a war-film (Haqeeqat) and “Would you like to join?” I said, “Yes, certainly.”

It was a challenge to me, as an art director, to recreate the atmosphere of Ladakh inside his studio. That was a big challenge. It, ultimately, gave me a Filmfare Award. I was an unknown person at the time. They didn’t know who I was. To me, also, it was new. For the first time, I was doing art direction in a film.

SB: You were talking about the Chinese occupying certain pieces of land and territory. Do you see any parallels today?

MS: Yeah, it’s a similar thing. They are claiming whatever areas they had claimed at that time also. So, it’s nothing new as such.

SB: But, if somebody made a film today it would be slightly different from Haqeeqat (1964). It would be very nationalistic and very jingoistic, wouldn’t it? The atmosphere in the country has also changed.

MS: Yeah, we have also experienced it. A lot of war films were made in India after Haqeeqat. During the first rule of the BJP, for example. In the name of patriotism, they made anti-Pakistani films, you know. And when you make an anti-Pakistani film, [the general public can perceive it as] anti-Indian Muslim – which is a very dangerous area. To deal with war is not easy. You have to be politically correct. I see that films like Border, Refugee and Farz and things like that – such films they were, no doubt, made with a lot of effort. They try to bring in reality in the war films. But it was the wrong approach. You can’t make an anti-Pakistani film because there are more Muslims in India than in Pakistan.

SB: So this actually brings us very well to Garm Hava. Now before we get on to the film, I just wanted to know – was it difficult to raise finance and get permissions? It’s quite a stinging story. It reminds a country what we’ve become, what we were at the time. How was it to try and set up the film?

MS: Actually, it all happened by accident. Garm Hava was not intended to be made at all. I had approached the Indian Finance Corporation and (B.K.) Karanjia sahab read the script (which I wanted to make). But then he said, “This is a very negative kind of story. Why don’t you give something else? Some other script? We would like to finance.” Then, Shama, my wife, who was writing the script, went to Ismat Chughtai and started talking about making a film. She narrated some stories from the days of the Partition which had happened in her own home in Uttar Pradesh. That’s how Garm Hava was thought of and then by accident, it was made. And with a lot of theatre people – a lot of theatre actors acted in this film.

If I say, it is almost like an IPTA film, I wouldn’t be wrong. It was an IPTA film in a way. It became a success. Although, I had a lot of problems getting a censor certificate. It took nearly 11 months to get a censor certificate.

SB: Why is that?

MS: There were a lot of apprehensions. They were unsure of – because, you know, the underdog – the Muslim – it is about them. And it is a delicate matter. How the nation would react to a thing like that was a question. It was very doubtful for the censor board to pass judgement on that. They were unsure. So, they delayed my certificate. Ultimately, I used a lot of influence. I knew Indira Gandhi personally. I knew Inder Kumar Gujral sahab personally – who was the minister of information at the time. When I showed them the film, I got through. A lot of politicians had seen the film by the time it was released. The Congress party saw it and then the opposition saw it. There was a lot of apprehension at the time.

SB: Was there any serious objection to it?

MS: No there was no objection as such. They were not sure. They were a bit doubtful about the whole thing.

SB: Did the Film Finance Corporation – which is a government agency – ever interfere while making the film? Saying “cut this” etc.?

MS: No, no, not at all. They just gave a small loan of Rs 2.5 lakh to make the film at that time.

SB: That’s it?

MS: No doubt, I had to spend much more. Nearly Rs 12-15 lakh. I think I spent it by borrowing money from my friends at that time. That’s how the film was made and released all over the world. But we had a lot of problems because of the delay in getting the censorship. All my distributors walked out.

The actual premiere of Garm Hava took place in Paris. The very first public show of the film was in Paris. Then, it got selected for the Cannes festival. It was recommended by a critic. It was shown at the main festival itself. There people from the Academy had come to see films and they selected Garm Hava for the non-English language film – for the Oscar. That by itself became sort of history, you know.

SB: I have to ask because this is a very important question for me and I’m sure people want to know about it. Was Balraj Sahni always in your mind for the role? He played the best role of his life in this film.

MS: Balraj Sahni and I were in the theatre together. I had worked for his Juhu Art Theatre and he was also in IPTA. He acted in my play – Aakhri Shama as Ghalib. There was a close association in a way and I admire his capability. Ideologically also, he was one with us. All these things helped. It was automatic for me to think of him as the lead person in the film.

SB: Where did you find talent like the ammi? The mother?

MS: Haan, the mother was a big problem actually. Begum Akhtar had agreed to do that role. But then at the last minute – when we were shooting in Agra – I got a message from her that she is unable to come because her husband doesn’t want her to act in films, although she had a film career much earlier. During Mehboob Khan’s film, she had acted. But then, I had to look for somebody in Agra.

We found this old lady. Her name was Badar Begum. She looked the part, although she was not an actress of any kind. She had only come to Bombay when she was about 16-17 years old to become an actress. But she couldn’t get an opportunity and had gone back to Agra. She had become a prostitute. When we went to meet her, she was running a brothel in Agra. But when I asked her if she would do the role and that I’m shooting in (R.S. Lal) Mathur’s house – in the haveli. I asked her if she would join the troupe. She started crying.

That was her life’s ambition – to become an actress – which she had failed. That itself is a very touching story.

SB: It’s certainly a very poignant story. Now, while making it, many of the actors must have remembered their own lives in 1947, the lives of their families and people’s own histories about one person going there, one not going there. It must have touched a lot of people even while making it. I mean, the impact is so great on the audience.

MS: Indian films which represented the Muslim lives showed a decadent life of nawabs, tawaifs, dancing girls and things like that. They never approached them as part of the Indian masses. That approach, I think, for the first time ever happened in Garm Hava. We became a part of the mainstream – which was not there before. They made a lot of films, except perhaps a few. For example, the representation of Muslims in V. Shantaram’s Padosi. There was a little bit of that but a real effort to show them as part of the Indian population was never there.

Minorities in India, like the Christian or Muslim minority, has not been really shown in a proper manner. That is unfortunate.

SB: The film has some magnificent scenes. The two scenes that haunt me include when Balraj Sahni walks into a room and sees his daughter lying there. We know there is a real-life history behind that and he must have been really shattered. The other is him telling the mother, “Let’s go.” And she tells him, “I’m never going to leave this house.” He says, “Don’t be stubborn.” You can see the man is broken. These two scenes – can you elaborate on their development?

MS: The scene where his daughter is dead – she has died by suicide. It was a bit cruel of me for him. This is exactly what had happened in his own life. His daughter had died by suicide. He was away somewhere in Madhya Pradesh canvassing for the Congress party for elections. This thing happened in Bombay.

When we traced, ultimately, the chief minister there – he gave a private, small aircraft on which Balraj came to Santacruz airport. I went to receive him there in my car and took him home. He walked straight up to Shabnam’s room, stood there at the door and saw his daughter dead, lying on the floor. By then, we had already got the coroner’s certificate because we didn’t want to wait for Balraj. In exactly the same way, I’ve shot the scene in Garm Hava.

He’s going up the staircase, opening the door and seeing the body of his daughter. There also, to explain the scene to him and what he should do – it was very difficult. All through I had to say, “It is Geeta who is lying dead.” I never even said, “This is your daughter.” “She has died by suicide. You open the door but no tears should come from you, at all,” I said. He opened the door and stood there silently.

In cinema-making, all these little acts of cruelty happen. I had to do that. I was really cruel to Balraj.

SB: How did he react?

MS: He understood the whole thing. He was a professional. As an actor, he was a professional. He had seen this personal tragedy earlier in his life. If there was a demand of the director or the scene, he would just do it. He would not mix them up. Emotionally, he never got upset that way.

SB: The second scene I was telling you about when he gets angry with his mother – but he’s really angry, in general, with himself and what’s going on. He says, “Come on, let’s lift her and take her.” That was also – a lot of people in the audience must have felt very attached to that scene because it reminded them of their life.

MS: That was a very well written scene. All the images that come when she says that line, “I want to go back to that haveli.” He takes her. The way she went to that haveli as a bride in a palki. She went to die there in the same way – in a palki. That’s how she first entered the haveli. And in the last part, it was also in the same fashion. That was a very touching sequence. She remembers the words and faces of people, old scenes come back to her.

SB: How was the film received by Indian audiences, especially by Hindu groups and by Muslim audiences? Did they have separate reactions?

MS: Yeah, there was a wrong kind of feeling, especially with Bal Thackeray. When the film was going to release at the Regal Cinema in Bombay, somebody had spoken about the film to Thackeray and he wanted to see it before it was released. I said, “Why should you see it before it is released? Why don’t you people come? The Shiv Sena can come to the premiere itself.” The premiere was being inaugurated by Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit – the Maharashtra governor at that time. But he said, “No, I want to see the film before the release.” Then, I organised a special screening for him and some of the Sena people. They all saw the film. But I didn’t go nor my partners went. We were not there at the screening.

He saw the whole film and he asked for me, “Where is the director? Where is the producer of this film?” They said, “He has not come, sir. They have just sent the print for you to see.” He said, “This is exactly what I want. The Indian Muslim should be a part of the mainstream. That is the message this film is giving.” There was no problem after that. This was only a kind of apprehension at the time.

Even L.K. Advani had written wrongly about the film in their newspaper, the party paper. He said that it looks as if this film has been financed by Pakistan. I mean, this is a comment which Advani made. Later on, when I met him sometime in Madras at a film festival, he said, “I’m very sorry, I made a mistake. I had not seen the film but I wrote it because I got a report from somebody about the film.” So he apologised for having written that.

SB: What did Muslims say? Did any Muslims tell you anything?

MS: No, there were some conservative Muslims who [expressed reservations], especially about the love affair between cousins. In a restricted atmosphere, in a Muslim family – these things do happen. I mean, cousins fall in love with each other because they don’t have the liberty to go out and meet people. Some Muslims said, ‘No, this kind of thing doesn’t happen’. Anyway, that was just a very personal reaction.

Generally, even the Muslim population in India liked the film.

SB: Did the film play in Pakistan?

MS: Yeah, pirated versions were there. Even today, Pakistan has a lot of pirated copies.

SB: Do you see, around you, something similar in India today as what happened with the Muslims in Indian society in the 1940s?

MS: Well, communally, the situation has become worse. [Indian society] had doubts about the loyalty of a Muslim. But today, Hindu fundamentalism has grown. A lot of communal clashes happen. I mean, this whole secular fabric is being damaged by the present government, the present rulers of this country. The BJP, in spite of having a Muslim governor in one state or a minister in the Centre – they’re only a show. They have a lot of money and have been bought and given positions. Basically, the BJP is an anti-poor and anti-Muslim group. This is what I feel.

A Kerala Muslim could not be accepted in Punjab. He had to look for other revenues like the Gulf countries or Saudi Arabia or go to Canada or something.

India still remains, basically, a secular country. And this secular fabric is very strong and very well-knit. It cannot be destroyed. No communal movement is possible in this country. The Indian ethos is that.

(Sidharth Bhatia is a journalist and writer based in Mumbai and is a Founding Editor of The Wire.)