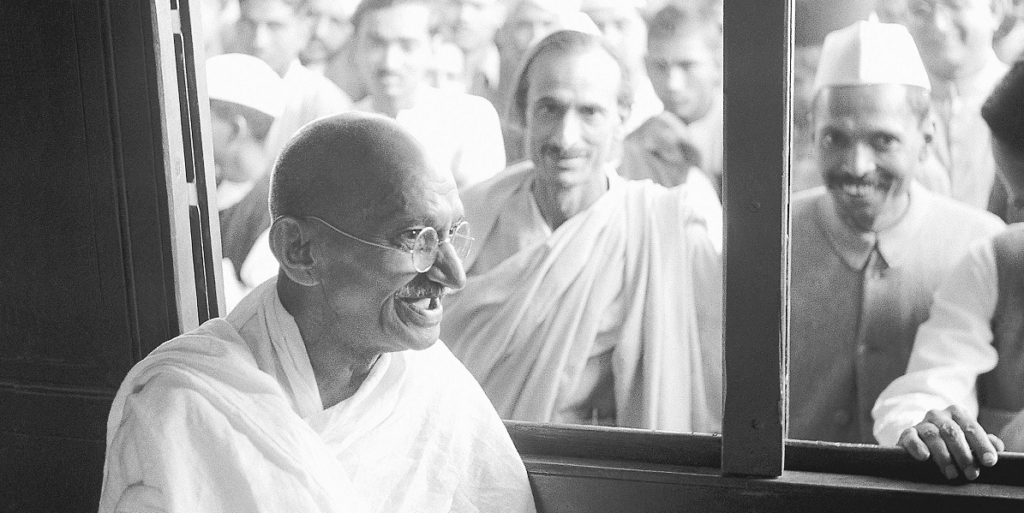

Exceptions apart, ritual bi-annual remembrance of Gandhi is all that is left of him in our lives. This is but a continuation of his periodic rejection during his own lifetime. This rejection was particularly pronounced towards the end of his life, and he was aware of it. For our part, we as a people let the fact lie buried under our protestations of his greatness.

Remembering him on his birthday, let us begin by reflecting on what he said on the only October 2 that he witnessed in Independent India:

Indeed today is my birthday…. This is for me a day of mourning. I am still lying around alive. I am surprised at this, even ashamed that I am the same person who once had crores of people hanging on to every word of his. But today no one heeds me at all. If I say, do this, people say, no, we will not…. Where in this situation is there any place for me in Hindustan, and what will I do by remaining alive in it? Today the desire to live up to 125 years has left me, even 100 years or 90 years. I have entered my 79th year today, but even that hurts.*

This, he knew, was tragic. Tragic not for himself, but for humankind, dukhi jagat as he would say. Just three-and-a-half months before he was killed, he said:

I will be gone saying what I am saying, but one day people will remember that what this poor man said, that alone was right.*

That alone is right. And ‘that’ includes many things. I shall stay with one of those things which, today, demand urgent consideration. It was more than a hundred years ago that Gandhi, in his Hind Swaraj, first articulated his fears about the self-destructive character of modern civilisation and proposed a radical alternative to it. As we writhe under the COVID-19 crisis, large numbers of us can see that history has since inexorably realised Gandhi’s fears. We are seized by a civilisational disaster.

But the general tendency still is to see the disaster as unprecedented, unexpected, even unimaginable. That induces two illusions. One, this is a natural disaster. Two, the solution lies in greater control over Nature. That control, as always, science will ensure for us. It will bring a vaccine, hopefully even a cure, rendering the virus ineffectual. As victims of what Gandhi called modern civilisation’s ‘tyranny of temptation’, these people will not see that the solution is the problem. That, like most ‘natural’ disasters, which now erupt with increasing frequency, COVID-19 is a by-product of the never-ending endeavour to conquer Nature.

Gandhi has explained why they will not see the obvious:

Those who are intoxicated by modern civilisation are not likely to write against it…. A man whilst he is dreaming, believes in his dream; he is undeceived only when he is awakened from his sleep. What we usually read are the works of defenders of modern civilisation, which undoubtedly claims among its votaries very brilliant and even some very good men. Their writings hypnotise us. And so, one by one, we are drawn into the vortex.

Gandhi offered an alternative to this irredeemably ruinous civilisation. At the heart of this alternative civilisation is swadeshi: “that spirit in us which restricts us to the use and service of our immediate surroundings to the exclusion of the more remote.” Translated into action, he explained, it would mean:

“In the domain of politics, I should make use of the indigenous institutions and serve them by curing them of their proved defects. In that of economics, I should use only things that are produced by my immediate neighbours and serve those industries by making them efficient and complete where they might be found wanting.”

If “reduced to practice,” he affirmed, swadeshi would “lead to the millennium.” His dream was that free India would usher in that millennium by adopting swadeshi and inspiring the rest of the world to follow its example. That is the way to save humankind from collective destruction.

For long has Gandhi’s swadeshi remained misunderstood, causing it to be at the same time celebrated and reviled. It has been – thanks to a misleading narrow understanding of the word desh – linked with the country and, by extension, with the nation. As a sequel, depending on how one views nationalism, swadeshi is as fatuously embraced as it is spurned.

This tendency is facilitated by the promiscuous utilisation of nationalism and globalisation so as to make the best of both worlds. Along with the arrogance of being a vishwa guru, a particularly insidious illustration of this comes in the call for atmanirbhar Bharat with its vacuous coupling of the local and the global.

Though Gandhi is not overtly invoked, there is in this strange melange a visceral appeal to his swadeshi. But, in its spirit and intent, it is a violation not just of Gandhi’s swadeshi but of everything he stands for. Gandhi does want India to follow swadeshi and inspire the rest of the world to follow suit, so that humans may live happily by being at peace with other humans and with Nature. But that entails no grand entitlement. His swadeshi is not about self-reliant Bharat. It is about self-reliant individuals. For it is these individuals who constitute Bharat. The essence of swadeshi is that “whatever is essential for human life should be individually controlled.”

In the civilisation envisaged by Gandhi, the village would be the basic unit of organised human existence. “I believe,” he wrote in his letter of October 5, 1945, to Nehru, “that if India, and through India the rest of the world as well, is to attain real freedom, then sooner or later we would have to live in villages – in humble dwellings, not in palatial mansions. It is simply not possible for millions of city dwellers to live in mansions happily and peacefully, nor by killing one another.”

Lest he be misunderstood, Gandhi clarified:

“If you think that I am referring to the village of today you will not be able to comprehend what I am saying. The village of my conception exists in my imagination as of now…. In the village of my imagination, the villager will not be inert – he will exemplify pure consciousness. He will not lead his life like an animal, in squalid darkness. Men and women will live freely and have the confidence to face the entire world. There will be no cholera, plague, or smallpox. Life will neither be slothful nor luxurious for anybody. Physical labour will be a must for everybody.”

Gandhi, then, proceeded to say something which deserves particular attention. It will disabuse those who – reading the Hind Swaraj as a frozen text and missing the organic nature of Gandhi’s thinking – cling to the belief that he was opposed to mechanisation. He wrote:

“Along with all this I can conceive of many things that would be built on a large scale: maybe railways as well as post and telegraph offices. What there will or will not be I can’t say, nor do I care. If I am able to establish the essential idea, the things for our future well-being will follow from it. But if I forsake the essential idea, I forsake everything.” *

The civilisational disease

The disease that Gandhi – borrowing from Edward Carpenter’s Civilization: Its Cause and Cure – saw in modern civilisation more than a hundred years ago has since become terminal. Still, convenient blinkers continue to mar people’s vision. The impossibility of humble dwellings and palatial mansions coexisting peacefully should not have escaped anyone after the experience of COVID-19. It does. Even after months of the so-called lockdown, not many have quite understood that, except for the super-rich and the better off among the middle classes, it simply meant an impossible situation for the rest, which means the overwhelming majority of Indians. The self-quarantine that the lockdown was meant to ensure, its prerequisite of social and physical distancing was simply unavailable to them. What, and for whom, have they been paying this enormous price? For whom is their immeasurable suffering?

The forced reverse exodus during the lockdown should have served to demonstrate the indispensability of villages. It has, instead, resulted in coercive legislative measures which are designed to sacrifice the local to the global, individual men and women to corporate interests. Gandhi dreamt of individuals – men as well as women – who would exemplify pure consciousness – shuddha chaitanya – and live freely. These measures reduce individual men and women into helpless instruments of a fake atmanirbhar Bharat.

Like never before, the COVID-19 crisis has made imperative the severe limiting of man’s violence against Nature and against fellow human beings. It has also, by the same token, underlined, like never before, the urgent need for an alternative, like Gandhi’s, to the civilisation of which COVID-19 is an essential fruit.

That precisely is what will not happen. Never in human history has the rightness and justice of something by itself been the reason for its realisation. Something additional, too, is required. This is the centenary year of the historic Non-Cooperation Movement. That was when Gandhi taught Indians that their fear was the basis of Britain’s rule over them. The moment they got rid of that fear and learnt to say ‘no’, British rule would be over. They, he famously said, India would have swaraj within a year.

The root of our enslavement to modern civilisation is our greed. There is no freedom – no future – unless we manage to overcome this greed. Unless we say ‘no’ to the tyranny of temptation. Otherwise, a solution that requires greater control over Nature and makes life so much more ‘fun’ will continue to trump one that requires control over ourselves and our fun.

*Translated from the Hindi original by Chitra Padmanabhan.

[Sudhir Chandra is the author of The Oppressive Present: Literature and Social Consciousness in Colonial India and Gandhi: An Impossible Possibility (both published by Routledge). Article courtesy: The Wire.]