Sudhir Chandra

We are surrounded by more of the same. The same ‘time-honoured’ prevarication, mendacity, and half-truths; the same lies, damned lies and statistics; and, sure enough, the same post-truth, which is but a new nomenclature for an old phenomenon.

Wittingly or unwitttingly, happily or sorrowfully, voluntarily or forcibly, we are complicit in it, even in the face of an unprecedented crisis in which everyone’s well-being depends on the well-being of everyone else, and truth is crucial to that well-being.

We must know what led to the COVID-19 pandemic, how it spread, what needs to be done, what the state of our preparedness is, what new problems are arising, where we are failing, and so on. No consideration can – should – at the moment be so critical as to override the need for truth about any aspect – not just medical – of this crisis.

Yet, truth is as scarce as ever. Forget China and the World Health Organisation, against which accusations of a sinister cover-up are mounting, there is not a single government in our own country, including the supreme one in Delhi, that we are ready to trust implicitly.

The governments themselves do not trust one another, confirming people’s distrust in them. There is an exception — Kerala — which no other government is ashamed of not emulating. Citizens do not look at the daily figures of new COVID-19 cases, deaths, recoveries, and tests as being completely reliable. Information about volatile issues like the rotten state of relief to the poor and trapped migrant workers across the country, particularly the information coming from the central and concerned state governments, is even more unreliable.

It is difficult not to remember Gandhi in the time of COVID-19. For one, the pandemic brings us back to his critique of the modern industrial civilisation, more particularly his much-maligned and misunderstood idea of swadeshi.

There is also something else that comes to haunt us in our present state of callousness towards truth and human suffering. For Gandhi, there was no consideration – not even the country’s unity – that could permit compromise with truth and concern for the poor, the oppressed and the persecuted.

That takes us to March 1947 – Gandhi’s last March – which he was forced to spend in Bihar. Five months prior to that, in October 1946, fierce anti-Hindu violence had broken out in Noakhali, a Muslim-majority district in the then East Bengal. The moment he came to know about it, Gandhi rushed to Noakhali with a view to cleansing the hearts of both the Hindus and the Muslims and bringing them together.

He had barely reached Noakhali, in the first week of November, when news started reaching him of brutal anti-Muslim violence in Bihar.

This placed him in a difficult dilemma. Bengal was then under a Muslim League government while Bihar was under the government of his own Congress Party. Determined to portray Gandhi as a partisan leader of the Hindus, the Muslim League used the anti-Muslim violence in Bihar to the hilt. No sooner had he reached Noakhali than the League leaders started taunting him about staying on in Noakhali to save its Hindus instead of rushing to Bihar to stop the carnage of its Muslims.

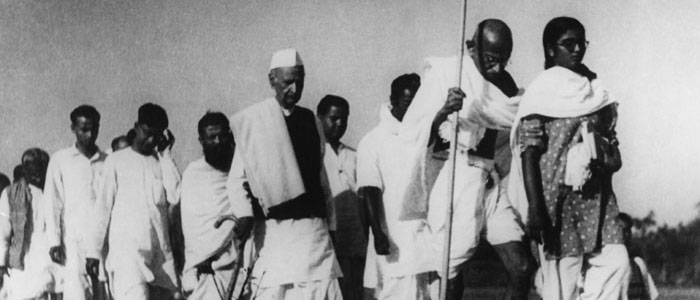

Gandhi stood his ground, convinced that if he succeeded in Noakhali, that would have a salutary effect on the entire country. Besides, he believed that the Congress government would not let the carnage in Bihar continue. He walked tirelessly from one village of Noakhali to another, bringing home to people, by personal contact, the message of peace and love.

He exhorted the Muslims to welcome back their Hindu neighbours, and the Hindus to shed their fear and, trusting in God, return to their homes among their Muslim neighbours. His was not the way of seeing peace and order enforced by the police and the military. That would for a while remove the manifestation of communal tensions and do nothing to remove the tensions.

We do not even remember what Gandhi’s way was.

Then came an SOS from Dr Syed Mahmud, a respectable Congress leader from Bihar, telling Gandhi that he alone could save the province’s Muslims. Gandhi left for Bihar forthwith. He reached Patna on March 5, 1947 and spent the rest of the month in the province. He knew that his coming would embarrass the Congress in general and the Bihar government in particular.

Efforts were made to persuade Gandhi that the violence in Bihar was carried out to malign the Congress by elements hostile to its ideology and programme. When he asked why the government had not instituted an enquiry, he was told that this would be used to embarrass the Congress government and party.

Those who could offer him that argument – his own long-time associates in the freedom movement – had obviously understood little of him.

Not one to be fooled, Gandhi embarked on his peace mission. He moved from one affected village to another, heard and spoke to the victims as also the perpetrators of the violence, held discussions with the leaders and workers of not just the Congress but also the Muslim League and the Hindu Mahasabha. Every evening he held his prayer meeting and ended it with a discourse in which he made a clean breast of whatever he had found out.

The violence in Bihar, Gandhi found out, had surpassed the violence in Noakhali. He made a clean breast of that too.

What pained him the most was the complicity of Congressmen even though the Congress as an organisation had not orchestrated the violence. Admonishing a gathering of Congress workers, he said:

“Is it or isn’t it a fact that quite a large number of Congressmen took part in the disturbances?… The Congressmen assembled here can themselves tell the truth. How many of the 132 members of your committee were involved? It would be a great thing if you could say ‘none.’ But that cannot be said….

“Why did you remain alive, I want to ask you. How could you bear to see an old woman of 110 being killed before your eyes? Leaving all other things aside, I want to raise just this question. I have decided that I will do or die. I will not rest nor let others rest. I will wander on foot. I will ask the skeletons lying about how it happened.”

Gandhi did wander from village to village in Bihar but agreed to travel by car, not on foot.

Seeing how the warring communities were blinded by a vicious cycle of action and reaction, he dwelt upon parallels between Noakhali and Bihar to show ordinary men and women the futility and foolishness of their passions. He said:

“I see here the same thing that I saw in Noakhali. Let no one say that if it happens there why should we not do it here…. That will mean competition in goondaism.”

Wherever he went he brought home to people the similarity between the savagery of the Muslims of Noakhali and the savagery of the Hindus of Bihar, as also the similarity between the foul methods employed by the aggressors to terrorise their victims. And he used this to ask: “Shall we meet barbarism with greater barbarism?”

Bihar filled Gandhi with forebodings. The Muslim League was bound to do whatever it could to precipitate the country’s partition. But what sort of freedom would India have if the Congress did not feel for and protect all Indians equally?

But the danger was larger than that. Treating all Indians as one was a responsibility – a duty – not limited to the Congress alone. It devolved on all those who believed India to be one and were opposed to its partition. Hindustan, Gandhi said, has many communities and we are responsible equally for all of them. He warned: “If we say that we are not, then our saying that Hindustan is ours will be completely wrong.”

Gandhi stood by truth even at the risk of his testimony being misused by the Muslim League to bolster its demand for Pakistan. It would say that even Gandhi had accepted that the Muslims were unsafe under the Congress. But that did not deter him. He knew that falsehood used for an immediate gain would come back to bite one eventually.

We inhabit a world the reigning wisdom of which is ‘whataboutery,’ the amorality of the idea and the infelicity of the term notwithstanding. In this world, where wrong is rife and nailing the wrong impossible, the figure of Gandhi is bound to evoke an anguished ‘alas.’ If only we had in our midst just one like him! One with similar integrity, detachment, compassion, vision, and quixotry.

[Sudhir Chandra is the author of Gandhi: An Impossible Possibility (Routledge) and The Oppressive Present: Literature and Social Consciousness in Colonial India (Routledge).]