“No Hindu ever reads the Mahabharata for the first time.”

∼ A.K. Ramanujan, Repetition in the Mahabharata, 1968.

Book Review

G.N. Devy

Mahabharata: The Epic and the Nation

Aleph Book Company, 2022

His soft-spoken and gentle demeanour is deceptive. Ganesh Narayan Devy is an angry man. But not in the least like the Bollywood template of the angry urban machine — an Amitabh Bachchan.

A literary historian and critic, Devy, for many decades, has been trying to understand the relation of culture, psychology and fiction with violence in India. Like the subversiveness of the epic, Devy’s Mahabharata is responding to our contemporary crisis in a schizophrenic India that continues to be fed by Hindutva pride: to offer a corrective text in the times of mass euphoria as to what Bharat has to be. Devy is reclaiming the Mahabharata to purge the threat posed by the Sangh parivar‘s distortion of history. In his own voice, he explicitly debunks the claims made by the Hindutva brigade, stating, “they hardly understand what the Mahabharata is or was”.

Writing in the late 1990s, Devy had forewarned us in Of Many Heroes that Indian literature is a historian’s despair. Is our history of the nation a history of violence? “I think violence is in the very heart of making ourselves into a modern nation,” he told me in an interview in the early ’90s in Baroda. “Literary history reflects the values of the society in which the historian lives, or for which he writes,” he said in his Of Many Heroes. “If in modern India there has seemed to have occurred a radical break with the Indian literary past, it has nevertheless occurred without a continuous intellectual battling with that past. The break shows no signs of being a historiographical rebellion; it is just a case of simple amnesia that colonisation inevitably causes.”

In Mahabharata: The Epic and the Nation, he owns the mantle of being a literary critic and frames the reading of the epic in the contemporary condition, with a responsibility to respond to three queries – the idea of belonging; history of India; and what is knowledge – offering arguments, strands of which are visible in his earlier works, a braided narrative of the ethnic, linguistic and epistemic to reflect the crisis in our democracy.

Persuasive presence

The often-repeated above quote by A.K. Ramanujan from his illuminating essay sounds like a cliché any time you mention the Mahabharata, yet for many, it is an aphorism. Mahabharata’s fluidity and its unconstrained nature have always invited a multitude of scholars, artists and writers into a conversation. After all these decades, I still vividly recall the 12-odd minute Mahabharata sequence from Kundan Shah’s Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro (1983). Memory aside, no one can deny the ubiquitousness of the Mahabharata in its pervasive presence in our lives. On my table, as I write this review, my Mahabharata universe is made up of an enigmatic work of fiction, The Dharma Forest by Keerthik Sashidharan, two volumes of Alf Hiltebeitel’s work on the Mahabharata as well as a slim booklet titled Reflection on the Mahabharata War by M.A. Mehendale.

Embedded in a Kathakali trope, Sashidharan’s approach to the Mahabharata is what Hilda Doolittle did to the great Greek mythologies. His is a modern retelling of the final days of the war through the eyes of Draupadi, Bhisma and Arjuna. Mehendale, the editor of the Epilogue to the Mahabharata, offered a push in the late 1980s to the Cultural Index component of the Mahabharata project at the Pune-based Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute (BORI). The project started in 1917 and was completed in 1966. It was a project on which three generations of scholars worked, resulting in a Critical Edition of the Mahabharata taking into account all the 1,259 manuscripts and recensions, and running into about 15,000 pages and a total of 19 volumes. By the turn of the century, the National Mission for Manuscripts was established, and the Critical Edition became the source of all Western scholarly quest on the epic. Hiltebeitel’s work, confirming the trend, argued for Mahabharata as history, as “the text calls itself about eight times, itihasa”.

Devy’s Mahabharata picks up the idea of itihasa, this-is-how-it-has-been, in his 142-page slim book with two pages for references and no index. From the Bharata, the bardic tale to the larger envelope of Mahabharata, he cautions to raise the right question – “not if the Mahabharata presents a history of its own kind, but why this kind of history received such widespread acceptance throughout India and continues to remain acceptable 2000 years later”. In doing so, he delineates the nuanced understanding as to why “the Mahabharata is yet not regarded by Indian people as a work of past because it brings to them the Mahabharata method of perceiving the past” despite the appropriation of the past of a nation being up for grabs by the far-right Hindu nationalist narrative.

So what is it about?

As if taking a clue from Vyasa, the author who imagines time in several forms – mythical, cosmic, psychological, historical – Devy begins to peel away the many layers of the text, its meaning, structure, language, grammar, characters, authors and the story, and concludes that “Mahabharata offers a method of presenting history which is never a complete objective truth nor a complete fiction, which is quite outside the realm either of fact or fiction, a universe within itself.” Given that the Mahabharata is entirely written in a variety of past tenses, Devy proposes, “it is about a method of understanding the past as a composite time, an aggregate of all aspects of Time, the Kala”.

As if with philosophical resignation, he concludes, “the unconscious metaphysics that the epic Mahabharata aims at articulating the metaphysics of Shanta (peace), and the metaphysics of being a sthitpragnya (established in wisdom), a Sakshi (witness/awareness).”

Given the “poetic energy, intellectual range, and philosophical depth” of the epic, he recognises the uphill task to offer exhaustive scrutiny. Halfway into the book, Devy wonders: “the question, however, is why a poet of Vyasa’s phenomenal poetic power would want to take recourse to myth when he would have simply written a great historical narrative?” Thus, he alludes to the imperative of Vyasa to “frame the historical narrative by completely submerging it in myth”. He is persuasive in arguing that the poet of Bharata “establishes a perspective of structuring historical narratives” and “a method of looking at history”. Upon its transition to the Mahabharata, Devy states, “it stuck to the epic’s vision of Bharata, a poem of grand synthesis”, highlighting the salient elements of “assimilation, synthesis, combination, acceptance, and moving forward without exclusions”.

Nation and its controlling text

The Mahabharata poses more questions than answers. “Why has the caste-divided Indian society still not become a ‘nation’, a substantially homogenous people, despite its exposure to the epic for thousands of years?” says Devy as he probes further: “Is it possible to read the Mahabharata as an epic of Time? …Would it be possible to understand the epic as a great poem of life and death? …What is it in the Mahabharata that gives it its timeless magic?”

There is something more fundamental that is driving his inquest: who are we and how did we get here?

After over five decades of studying literature, for Devy, his book on the Mahabharata is not a humanist nostrum. He poses a direct question: “Is there something in the nation-epic relationship that has escaped the attention of its critics?” His engagement emerges from a deeper site of inquiry where he does not dwell on what is the relationship of this greatest literary work with our people, but rather he delves into how this relationship functions. Thus, he situates the Mahabharata as an analytic.

Apart from some primary questions, like who is the poet or what is the purpose of epic, Devy’s book is a personal inquiry defining his relationship with the text, his engagement with the epic and what it means to him.

He continues to use the Mahabharata as an idiomatic device or plain analogy in his commentaries, whether on the farmers’ protests or the current hijab issue; his writing of this book amplifies the urgency at hand. It brings to focus the central argument about a vision of history and vision of society, and how the epic is a reminder of the larger tradition of the nations to today’s India. The allure of the Mahabharata and how it provides insight into its cultural memory in India could be best explained through the idea of a controlling text – a reference point for all thinkers and a recourse to fall back on for the nation.

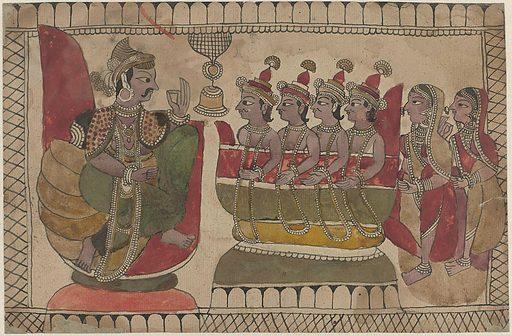

In a prescient observation made to me in an earlier conversation, he said: “The point is every time when India tried to forge ahead, to modernise, the Gita has become important because violence has become important as a social issue.” However, in the book, he skirts away from discussing the Gita per se and allows it to be subsumed by the epic. We all know and recognise the visual preface; the Gita emerges as a shorthand for the entire corpus of the Mahabharata – the very iconography in the image of Arjuna on a chariot with Sri Krishna as the charioteer is pervasive in our midst, as is its acceptance as legitimate text to take a legal pledge on. So it doesn’t come as a surprise when Tulsi Gabbard took an oath of office on the Bhagwad Gita as a new member of the House of Representatives in Washington DC.

At ease with the mythical and the political, Devy has never shied from the non-conformist paths of inquiry. In After Amnesia (1992), Devy argued that colonialism turned the Indian intelligentsia into a society of amnesiacs. Despite his prolific writings and interventions into the social and political world of ideas, I believe this book on Mahabharata’s relationship with the Indian psyche and society is as fundamental as was his trailblazing work on literary theory, After Amnesia. As we mark two decades since the genocide in Gujarat, this book is an act of moral courage. Here’s an incandescent articulation of moral courage, that is different from warriors’ courage.

The killings of a rationalist, an intellectual and a writer – Narendra Dabholkar, M.M. Kalburgi and Gauri Lankesh— hastened his decision to move to Dharwad in the south of India from Baroda. With his Dakshinayan movement for the fight for justice for Kalburgi and with this book, he does not shy away from the larger battles, demonstrating how to fight the politics of ideas and minds.

Given his dry sense of humour, I can hear Devy whisper, holding his slim volume in hand, addressing the Mahabharata, “Others abide our question. Thou art free.”

(Narendra Pachkhédé is a critic and writer who splits his time between Toronto, London and Geneva. He was G.N. Devy’s student at the M.S. University of Baroda in the 1980s. Courtesy: The Wire.)