Months into the Occupation, a visitor arrived on Alcatraz Island. Chosen by the elders to reveal the traditional wisdom and prophecies of the Hopi Nation, Thomas Banyacya had come to bear witness to a new chapter in Native American resistance.

Genocide and federal assimilationist policies had cut the “tree of life” off at the base, he told LaNada [Boyer] War Jack and the other young Native leaders assembled on The Rock. When the Indians of All Tribes seized Alcatraz on November 20, 1969, the tree had once again begun to grow.

Fifty years later, the sprouts that first germinated on Alcatraz Island have matured into a broad canopy thick with Indigenous activism. A direct line traces the path of pan-Native activism from the 1969 Occupation of Alcatraz to the 10-month standoff over the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock three years ago. War Jack has been there every step of the way.

The 19-month Occupation of Alcatraz by Native American activists was a direct result of centuries of Indigenous resistance to the systematic destruction of homeland, culture and identity perpetrated by the federal government of the United States. That’s the argument War Jack makes in her new book, Native Resistance: An Intergenerational Fight for Survival and Life, being released this month.

When, in 1956, the Bureau of Indian Affairs launched yet another assimilationist policy, the Indian Relocation Act, the intention was to further undermine Native communities by moving youth from Indian Reservations to urban centers throughout the West. Instead, the opposite occurred. Native people began, for the first time, to find support across tribal lines among the more than 100,000 relocated Indigenous people who shared similar histories of Indigenous identity and cultural survival.

In her book, War Jack describes life for the approximately 15,000 people who were transferred to the San Francisco Bay Area. “I think the Bay Area was just magic for us,” War Jack explains, recalling that period. A Bannock-Shoshone, she had transferred to San Francisco from Idaho’s Fort Hall Reservation under the relocation program in 1965. She was 18. “There was electricity at that time. It was like the perfect storm ready to begin.”

Enrolled three years later as the first Native American student at UC Berkeley, she began recruiting other Indigenous students to campus. They formed the Native American Student Organization and she was elected chair. In early 1969, when the Third World Liberation Front, a coalition of minority ethnic student groups on campus, rose up to strike for greater representation in academia, War Jack was among its leaders.

For Native American students at San Francisco State University and other schools around the Bay Area, the protests and strikes at University of California, Berkeley during the 1960s, were a glimpse into how political activism could begin to address the injustices Native people had long suffered. In meetings at San Francisco’s American Indian Center and Warren’s, a bar in the Mission District’s “Little Res,” a plan was hatched to take over Alcatraz Island, whose world-famous prison had recently been decommissioned and its land declared “surplus.”

The siege of Alcatraz officially began on November 20, 1969, with two major goals — to agitate for Native American self-determination and sovereignty and to establish a Native American cultural center, museum and college on the island. In the 1960s, War Jack says, “just to identify yourself as a Native person would bring immediate discrimination and racism. [Alcatraz] helped us re-establish our self-identification as Native people. People developed pride.”

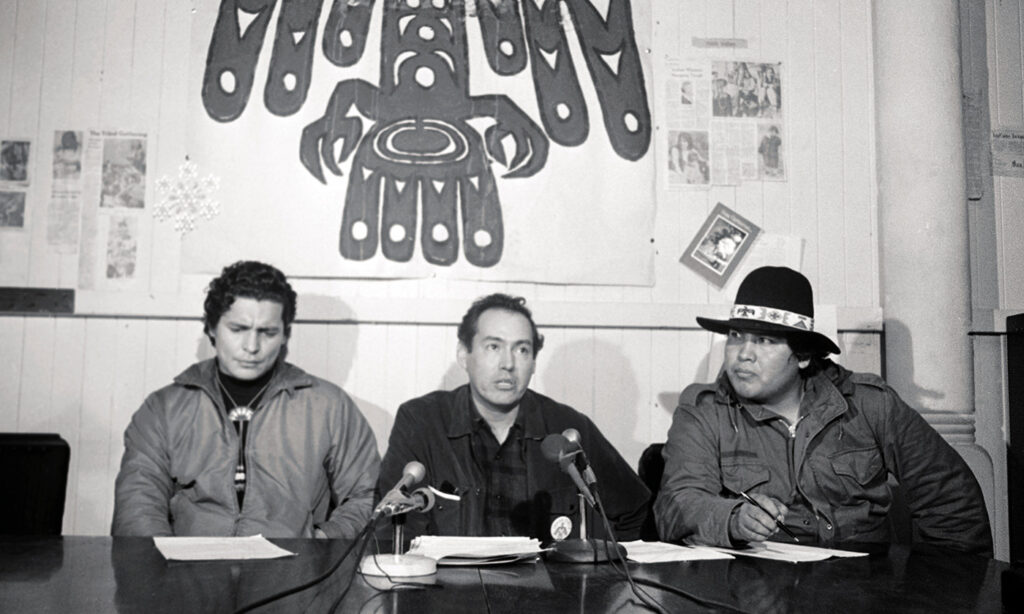

Indeed, within days the numbers of Indigenous men, women and children on Alcatraz swelled from the 89 who landed on the island’s rocky shore in the early morning hours of November 20 to close to 1,000 by Thanksgiving Day that year. Led by a governing council that included Mohawk Richard Oakes, whom the press christened the movement’s leader, Indians of All Tribes, quickly released their demands and set about establishing a school, health center, nursery, library and security force among the ruins of Alcatraz prison.

Donations poured in, and the message of the occupiers was amplified across the country, igniting a number of other Native occupations and protests in the months to follow, including the March 1970 invasion of Fort Lawton in Seattle and the takeover of a Bureau of Indian Affairs Office in Denver. “[Alcatraz] inspired a lot of people not to just give up but to keep going,” War Jack says.

In its first six weeks, the Occupation of Alcatraz hummed smoothly along as negotiations with the federal government got underway. Then, in early January, the stepdaughter of de facto leader Oakes fell to her death from the third floor of an abandoned apartment building on the island.

Oakes packed up his family and left. The ensuing power-struggle, as well as accusations of drugs, violence and the misappropriation of donations, began to seep into the media. At the end of May 1970, the federal government shut off all electrical power to Alcatraz. Two nights later, several buildings burned in a massive fire. Without electricity and a source of fresh water, the Occupation hobbled along for another year until, on June 10, 1971, the group was finally forced off the island.

In the end, the conclusion of the Occupation marked a new beginning for Native people. Almost immediately, President Richard Nixon ended Public Law 280, which gave states legal jurisdiction over reservations, increased budgets at the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Indian Health Services, and gave back millions of acres of tribal land.

On the national stage, the American Indian Movement, founded in Minneapolis in 1968, took up the mantle of Native activism while protests and occupations erupted around the country. It’s a wave of consciousness that has only grown over time. During the 10-month standoff over the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock in 2016, thousands of Native people and non-Native allies participated in a protest that, thanks to social media and the hashtag #NoDAPL, was heard around the world. Even on The Rock, Native people are finally getting recognition. An exhibition on the Occupation and 19 months of Indigenous-organized cultural events will launch at Alcatraz Island National Park on November 20, the 50th anniversary of the takeover.

While the battle against injustice and disenfranchisement is far from over—in fact, says War Jack, the government “is going completely in reverse” in its dealings with sovereign Native people—the Hopi prophecy still rings true: “We’re growing and we’re coming back…it’s the spirit of resistance that continues.”

(Shoshi Parks is a freelance writer and anthropologist specializing in history and travel. Article courtesy: Yes! Magazine.)