France Losing its Military Bases in Africa, Tries to Reorganise; Sahel Nations Take Steps to Strengthen Their Autonomy – 4 Articles

❈ ❈ ❈

Adieu: Africa’s Military Breakup with France is Official

Tamara Ryzhenkova

France is about to completely lose its military presence in the Sahel region and West African nations, following statements by Senegal, Chad, and Cote d’Ivoire in late 2024 expressing their intent to terminate military contracts with Paris.

Earlier, French troops left Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. The interim governments of these countries, formed after military coups, no longer want to cooperate with their former colonizer and aim to unite under a new confederation known as the AES, Alliance of Sahel States. These nations have also opted to leave the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), viewed as a tool for maintaining French influence in the region.

Chad

On November 28, 2024, the government of Chad announced that it is terminating its defense agreement with France, which was signed on September 5, 2019.

“The government of the Republic of Chad informs national and international public opinion of the decision to end the defence cooperation agreement signed with the French Republic,” the statement from the Chadian Ministry of Foreign Affairs says.

The deadline for the withdrawal of French forces from Chad was set for January 31. As of 2024, approximately 1,100 French troops were stationed in Chad under a 1978 agreement that was revised in 2019.

On January 30, 2025, Chad’s General Staff announce that control over the last French military base, the Adji Kossei military base in the capital city of N’Djamena, had been officially handed over to the Chadian Army. Control over the other two bases, located in Faya in the north and Abeche in the east of the country, were handed over on December 26 and January 12, respectively.

N’Djamena has also refused military support from Washington. Just a few months earlier, in April 2024, the Chadian government sent a letter to the US announcing its intent to terminate the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA), which allowed for a US military presence in the country. The letter specified that all US troops were to leave the military base in N’Djamena. By April 25, the Pentagon confirmed it would withdraw 75 of its servicemen from Chad, although it characterized this move as “temporary.”

This situation raised concerns in the US that it would lose its influence in the Sahel to nations like China and Russia. These fears were compounded by a meeting in January between the president of Chad, Mahamat Idriss Deby Itno, and Russian President Vladimir Putin in the Kremlin. Their encounter signaled Chad’s intention to move away from decades of pro-Western policy and look eastward, following the example of Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso.

Senegal

On November 29, 2024, the day after the statement by Chad’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Senegalese President Bassirou Diomaye Faye told AFP that France would have to close its military bases in Senegal.

“The presence of French military bases is incompatible with Senegal’s sovereignty. Senegal is an independent country, it is a sovereign country, and sovereignty does not accommodate the presence of military bases in a sovereign country,” he said.

Faye, who became president in April 2024 and pledged to support the country’s sovereignty and break free from foreign influence, clarified that the choice to expel French troops did not mean that Dakar would sever ties with Paris.

He also said that he had received a letter from French President Emmanuel Macron in which Parisclearly and unequivocally acknowledged its responsibility for the Thiaroye massacre, committed by French colonial troops near Dakar on December 1, 1944. On that day, up to 400 Senegalese soldiers, known as Tirailleurs, who had fought in the Second World War as part of the French colonial forces, were shot by their own commanders under the pretext of a mutiny, stemming from unpaid wages. Faye welcomed this acknowledgment, viewing it as “a great step forward” from Macron.

Faye also noted that Senegal maintains strong ties with several nations, including China, Türkiye, the US, and Saudi Arabia, which do not have military bases in Senegal.

On December 27, 2024, Senegal’s prime minister, Ousmane Sonko, announced the closure of all foreign military bases in the country. While he did not specifically name France, this is clear since French troops are the only foreign forces present in Senegal. France is expected to hand over all the bases in 2025.

Currently, a unit of the French Marine Corps operates in Senegal, primarily consisting of military instructors involved in the comprehensive program known as the ‘Reinforcement of African Peacekeeping Capacities’ (RECAMP), an initiative launched in the late 1990s with the involvement of France, the UK, and US.

In 2010, France closed its military base in Senegal but retained an air base at Leopold Sedar Senghor International Airport in Dakar. Additionally, French military equipment necessary for peacekeeping operations remains stationed in the country.

By mid-February, officials from both nations agreed to establish a special commission to oversee the transfer of the bases and the withdrawal of approximately 350 French soldiers from Senegal by the end of 2025. The decision was announced in a joint statement by the foreign ministers of France and Senegal.

“The two countries intend to work towards a new defense and security partnership that takes into account the strategic priorities of all parties,” they stated.

Cote d’Ivoire

On February 20, 2025, France officially handed over its only military base in Cote d’Ivoire to the local authorities. This was announced on the French mission’s official webpage. On December 31, 2024, President Alassane Ouattara said that all French troops would be withdrawn from the 43rd BIMA marine infantry battalion at Port-Bouet starting in January. Located in a coastal suburb of Abidjan, Port-Bouet is home to an international airport and an autonomous port, where around 500 French soldiers were stationed. This withdrawal is part of a broader effort to strengthen the country’s own defense capabilities.

“We can be proud of our army, whose modernization is effective. It is in this context that we have decided on the concerted and organized withdrawal of French forces in Cote d’Ivoire,” Ouattara said.

African Frexit

The public and media have dubbed this collective expulsion of French forces, initiated by the governments of the former French colonies, the ‘African Frexit’. The people in these countries showed widespread support for the decision of the authorities, since they were weary of terrorist threats which have persisted despite the presence of thousands of French soldiers and military instructors. Armed groups have turned the Sahel and West Africa into persistent hotspots of violence.

In Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, organizations such as Jama’at Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM), affiliated with Al-Qaeda, are waging a full-scale war against government security forces. Armed factions are increasingly launching attacks in coastal areas of Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, and Benin. It is understandable why the regional authorities are reevaluating their counterterrorism strategies, reforming military structures, enhancing national defense capabilities, and seeking support from countries like Russia.

The reaction of Paris

In reaction to Chad and Senegal’s decisions to terminate military agreements, French President Emmanuel Macron accused them of forgetting to express gratitude for France’s support in the fight against terrorism since 2013.

“I think someone forgot to say thank you. It does not matter, it will come with time,” Macron said during his annual address to French ambassadors.

His comments referred to Operation Serval and Operation Barkhane – French military operations that targeted Islamist groups in the Sahel region. Macron further said that “None of them would be a sovereign country today if the French army had not deployed in the region.”

These statements were strongly condemned by both N’Djamena and Dakar. Chad’s foreign minister, Abderaman Koulamallah, described Macron’s remarks as “disrespectful” towards Africans and reminded him of the “crucial role” Africa and Chad played in liberating France during both World Wars – something he claimed “France has never truly acknowledged.” Senegalese Prime Minister Ousmane Sonko echoed this sentiment, accusing France of destabilizing Sahelian nations: “This is finally the place to remind President Macron that if African soldiers, sometimes forcibly mobilised, mistreated, and ultimately betrayed, had not deployed during the Second World War to defend France, it would perhaps still be German today,” Sonko said.

France attributes its setbacks in Africa to political events. In the same speech to ambassadors, Macron explained that French troops are withdrawing from African nations due to coups and the rise of new governments that France does not recognize as legitimate.

“We were there at the request of sovereign states that had asked France to come. From the moment there were coups d’état, and when people said ‘our priority is no longer the fight against terrorism’… France no longer had a place there because we are not the auxiliaries of putschists.”

In light of recent developments, French media outlets have observed that Africa holds limited economic interest for the Fifth Republic. In 2023, Africa accounted for just 1.9% of France’s external trade, 15% of its strategic mineral supplies, and 11.6% of its oil and gas imports. Moreover, France’s largest trading partners in sub-Saharan Africa are Nigeria and South Africa – former British colonies which had never hosted French military bases.

What is left?

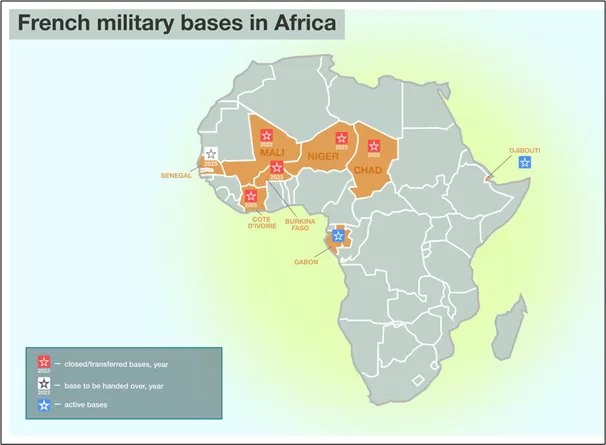

Until recently, France had military bases in at least eight African countries: Mali, Niger, Chad, Cote d’Ivoire, Senegal, Burkina Faso, Djibouti, and Gabon. Additionally, since 1990, the French Navy has been active in the Gulf of Guinea and off the West African coast as part of ‘Mission CORYMBE’, which safeguards French economic interests in the region.

However, in the past three years, six countries have severed military agreements with Paris. By August 2022, French forces had completely withdrawn from Mali, and in February 2023, Burkina Faso announced that it was expelling French troops. By December of the same year, France handed over all its military bases in Niger to the local authorities. As previously mentioned, by January-February 2025, French troops had fully withdrawn from Chad and Cote d’Ivoire, and plan to leave Senegal by the end of the year.

Djibouti and Gabon remain the only two African nations where France still has a military contingent. According to a defense cooperation agreement signed in 2011, Djibouti hosts the largest French military contingent in Africa (around 1,500 servicemen). This small nation, strategically located along the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait, is home to five French naval and air bases. However, French troops aren’t the only ones stationed in Djibouti – the country also has at least eight foreign military bases, including those of the US, China, and Japan.

At the end of December, Macron visited the 1,500 French troops stationed in Djibouti. Addressing the personnel, he emphasized the strategic importance of the Djibouti military base for Paris.

“Our role in Africa is evolving because the world in Africa is evolving-public opinion is changing, and governments are changing,” he said.

French troops have been present in Gabon since the country became independent in 1960. This is cemented by defense agreements established that same year. Currently, around 350 French soldiers are deployed in Gabon. Despite the deep historical and economic ties between the two nations, France’s influence in the region is declining and calls to reduce foreign influence are spreading in Gabonese society.

Seeking alternatives

Nevertheless, France appears to be exploring alternative avenues to maintain its standing following the loss of its military bases in Africa. One potential ally in this endeavor could be Mauritania. At the end of January 2025, the Delegate General for Armaments in the French Ministry of Armed Forces, Emmanuel Chiva, delivered advanced military and electronic equipment to Nouakchott. This shipment included combat vehicles, motorcycles, engineering tools, fuel tankers, and mobile repair shops.

According to official statements, this military assistance aims to bolster the Mauritanian Armed Forces in their fight against illegal immigration, cross-border crime, and terrorism in the Sahel region. It’s worth noting that this collaboration benefits Mauritania as well, given the recent threat from the Polisario Front due to Nouakchott’s growing ties with Rabat. Amid the escalating tensions between France and Algeria, which supports Western Sahara, this assistance seems quite reasonable.

Since the closure of military bases was announced by African leaders rather than Paris, this is a clear sign that Africa is rejecting French policies. Macron now has to deal with the decline of French influence in Francophone Africa – a region long viewed as Paris’ geopolitical backyard. Meanwhile, countries in the Sahel and West Africa are actively forging partnerships with external players like Russia, Türkiye, China, India, and the UAE, moving away from the historical connections that once tied them to Europe.

(Tamara Ryzhenkova is senior lecturer at the Department of History of the Middle East, St. Petersburg State University, and is an expert for the ‘Arab Africa’ Telegram channel. Courtesy: RT, a Russian 24/7 English-language news channel which brings the Russian view on global news.)

❈ ❈ ❈

French Neocolonialism in Africa Reorganizing Under the Cover of Retreat

Pavan Kulkarni

In his New Year’s address, Alassane Ouattara, president of Ivory Coast since 2010—when he took power with the aid of French military intervention—announced, “We have decided on the coordinated and organized withdrawal of French forces” from the country.

However, his address didn’t mention terminating the 1961 military agreements with France. These “agreements are at the root of the problem. As long as these agreements exist, France will be able to use them to carry out military maneuvers or intervene at the request of its servants in power in Ivory Coast,” general secretary of the Revolutionary Communist Party of Ivory Coast (PCRCI), Achy Ekissi, told Peoples Dispatch.

The only concrete commitment made by Ouattara in his speech was that “the camp of the 43rd BIMA, the Marine Infantry Battalion of Port-Bouët, will be handed over to the Ivorian Armed Forces as of January 2025.”

Originally known as the 43rd Infantry Regiment, and established in 1914 as a detachment of the French colonial army in Ivory Coast, this battalion served France “during both world wars, the Indochina War, and the Algerian War. In 1978, it was renamed the 43rd BIMA without altering its primary mission: safeguarding imperialist interests, particularly those of France, monitoring neocolonial regimes, and intervening militarily when necessary to uphold the neocolonial order,” PCRCI said in a statement.

Directly under French command, this battalion “is one of the visible faces of French domination in Ivory Coast,” which the former colonial power needs to invisibilize to salvage the last few military footholds it has left in its former colonies in the West African region.

France Reorganizing Toward ‘A Less Entrenched, Less Exposed Model’ of Military Deployment

“We have bases in Senegal, Chad, Ivory Coast, and Gabon. They are located in capital cities and sometimes even within expanding urban areas, making their footprint and visibility increasingly difficult to manage. We will need to adapt our base structure to reduce vulnerabilities, following a less entrenched, less exposed model,” General Thierry Burkhard, Chief of Staff of the French Armed Forces, reckoned in January 2024.

By then, France had lost its major bases in the region. Amid a wave of protests against France’s continued economic and military domination of its former colonies, the regimes it had backed in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger were removed by coups, supported by the anti-colonial movements.

The popularly supported military governments replacing them ordered the French troops out. Enduring sanctions, threats of a France-backed military invasion, and attacks by terror groups it allegedly supports, the three neighboring countries united to form the Alliance of Sahel States (AES).

Reenergized by their success, the popular movements in other countries listed by Burkhard were growing, posing an increased threat to the French bases and its allied regimes, increasingly perceived as French puppets in the region.

Less than three months after the general had stressed the need for a “less entrenched, less exposed model” of French military deployment in this region, Macky Sall, who was then Senegal’s France-backed president, was ousted by popular vote in the March 2024 election. Promising to free Senegal from the yoke of French neocolonialism, the then-opposition leader Bassirou Diomaye Faye won the election, despite preelection violence and a crackdown by Sall’s government.

“Senegal is an independent country, it is a sovereign country and sovereignty does not accept the presence of [foreign] military bases,” President Diomaye told AFP in late November 2024. French military foothold in Senegal, the first in General Burkhard’s list of four former colonies where the last of its military bases were to be salvaged, is all but lost. Diomaye announced in his New Year speech that he had instructed his defense minister to draft a new policy ensuring the withdrawal of all foreign troops in 2025.

Electoral Threat to French Interests in Ivory Coast

“France does not want to find itself in a situation like in Senegal, where the pro-imperialist camp was wiped out by Pan-Africanists” in the election, Ekissi explains. Ivory Coast’s former President Laurent Gbagbo, who was bombed out of office by the French military in 2011 to bring Ouattara to power, is challenging Ouattara in the presidential election due in October 2025.

Ekissi described Gbagbo as a socialist who was “sometimes anti-imperialist and Pan-Africanist, but hesitant in directly combating French interests” during his presidency from 2000 to 2010. Anti-imperialism directed against France was not a part of the populist politics in the early years of his rule. Such politics was mostly limited to the small Communist Party, which was founded in 1990. But that was about to change.

Soon after Gbagbo took office in 2000, the Socialist Party-led coalition running the French government lost power in 2002. “The liberal wing of French imperialism, which had come to power, could not allow Gbagbo, a socialist, to lead the most important French neocolony in West Africa,” added Ekissi.

Civil War

Taking advantage of the discontent that had been brewing in the Muslim north, which had for decades felt marginalized by the Christian south, France helped Ouattara organize an armed rebellion in 2002.

After serving as the prime minister during the last three years of the one-party France-backed dictatorship of Félix Houphouët-Boigny—president of the country since independence in 1960 until his death in 1993—Ouattara had been marginalized in the succession race within the ruling party, which he then lost to Gbagbo in the 2000 election.

Following a five-year stint in the IMF as its deputy managing director from 1994 to 1999, Ouattara returned to domestic politics by starting a civil war in 2002 and dividing Ivory Coast’s army.

In the meantime, French troops “positioned themselves between the two armies, splitting Ivory Coast into two.” Repressing anti-French protests with massacres that killed hundreds in 2002 and again in 2004, French troops positioned themselves to become the key player in the crisis, which ended with the ouster of Gbagbo in 2011.

The election in 2010, in which Ouattara contested against Gbagbo, was “manipulated by France,” Ekissi maintained. Defecting to Ouattara’s base at a hotel in the capital Abidjan, guarded by French troops under the UN’s cover, the election commission’s president announced that Ouattara had won with 54.1 percent of the vote.

However, the country’s Constitutional Council declared the announcement as “invalid” as it was made after the deadline had expired. It thus reversed the verdict in favor of Gbagbo, citing “irregularities” in the results submitted by the election commission.

French Bombardment of Ivory Coast’s Presidential Palace

In the months after Gbagbo’s swearing-in ceremony in late 2010, French troops, operating mainly from the 43rd BIMA, killed thousands of soldiers and protesting civilians defending Gbagbo, Ekissi recalled. Finally bombing the presidential palace in April 2011, France helped Ouattara’s forces capture Gbagbo.

Accused of crimes against humanity, Gbagbo became the first former head of state to be tried at the time in the International Criminal Court (ICC) in Hague. Almost eight years after his arrest, he was acquitted in 2019. The prosecutors’ appeal against his acquittal did not succeed. The ICC upheld his acquittal in 2021, following which he returned to Ivory Coast.

In March 2024, Gbagbo declared his candidacy for the presidential election in October 2025. The popular support he enjoys today is “unequivocal,” said Ekissi. And the popular movement against France is today stronger than ever before.

In the early years of Gbagbo’s administration, after the civil war broke out in 2002, “people had already come to understand the full extent of France’s ruthlessness, criminality, and manipulations,” Ekissi explained.

The anti-imperialist politics had begun to spill out of the confines of the left and consciously pan-Africanist organizations and into the populist domain. But the “hesitant leaders” of Gbagbo’s party “had not allowed it to flourish.”

‘A Rallying Cry of the Ivorian People’

However, after 2011, following France’s bombardment of the presidential palace and killing of Ivory Coast’s soldiers and civilian protesters, “the call for the unconditional withdrawal of French troops from Ivory Coast has become a rallying cry of the Ivorian people,” maintained the PCRCI.

“Pan-Africanist and anti-imperialist victories in the AES countries have further galvanized the movement against France in Ivory Coast,” added Ekissi. Ouattara’s “imprisonment of human rights activists visiting Mali, Burkina Faso, or Niger for up to six months,” has not succeeded in quelling the growing domestic popularity of the AES example. “Today, even the right wing or so-called centrist parties, historically opposed to any emancipatory struggle, dare not openly attack” the AES countries.

The demand for French withdrawal, initially championed only by the communists and Pan-Africanists, is now being raised by all major opposition parties. After Gbagbo emerged as a credible electoral threat to Ouattara’s regime, the government barred him from contesting.

The stated reason was that, months after his acquittal by the ICC, the Ivorian judiciary had convicted him in absentia in 2019 of robbing the Central Bank, which he had nationalized. Arguing that he was “unfairly” convicted, Ekissi pointed out that “the Central Bank had never filed a complaint” against Gbagbo.

Relying on several legal arguments, his party has nominated him despite the government taking his name off the electoral roll. Other opposition parties are also growing increasingly assertive in their demand that the election must be “inclusive.”

With the prospect of the electoral defeat of Ouattara by a Pan-Africanist coalition on the horizon, France has been unable to find a replacement for him, Ekissi explained. “It could accompany Ouattara in his madness to win these elections in blood. But this is a big risk, against which Senegal’s result is a warning.”

Feigning a Retreat to Confuse the Sovereignty Movement

Instead, France is feigning a retreat in an attempt to “confuse the sovereignty movement, while waiting for an opportunity to reposition itself in the ‘center,’” camouflaging its military presence in the meantime, Ekissi argued.

This decision, in line with the strategy articulated by Burkhard, requires France to get rid of its direct command of the 43rd BIMA, the country’s most visible and provocative structure of neocolonialism.

It was not Ouattara’s decision to expel French troops from this base, the Communist Party maintained, arguing that it was rather France that decided to hand over this “land asset” to the army of Ivory Coast to get rid of its visible presence.

But “there are light bases in Assini, Bouaké, and Korhogo,” Ekissi pointed out, adding that U.S. troops expelled from AES countries have also set up a base in the Odienné region along the borders with Mali and Guinea.

The French army has also established an international counter-terrorism school in the coastal town of Jacqueville. It is a part of the NATO countries’ effort “to prepare destabilization operations to target the AES countries, and carry out surveillance and ‘neutralization’ of supposed Russian advances in the region,” he said.

By merely receiving command of the 43rd BIMA, while retaining other smaller foreign military bases, training schools, and the 1961 military agreements with France, Ouattara is only helping “to hide its army from public view,” Ekissi said.

“The imperialist power, sensing its end, is trying to protect its military power in the region with a new strategy,” involving a “minimal physical troop presence” scattered over “small mobile bases,” while “multiplying its training schools” and increasing “assistance operations,” added Ekissi.

Tried and Tested in Benin

“Since February 2023, Benin has served as the testing ground for this new military strategy,” the Communist Party of Benin (PCB) said in a statement. The increasing number of French troops arriving that year after their expulsion from the AES countries set up camp next to the Beninese military base in the Kandi region in the country’s north.

After this provoked a public backlash, the French presence was downsized in the region. French troops still operate from Kandi late at night, flying “military equipment and personnel to the airport constructed in the W National Park, located at the intersection of Benin, Burkina Faso, and Niger.” But they are fewer in number, and do not maintain a high visibility in Kandi anymore, PCB’s first secretary Philippe Noudjenoume told Peoples Dispatch. “Another more discreet base has been constructed further inland near Ségbana.”

New camps, which the Beninese government calls “advanced posts,” have been cropping up “along the borders with Niger and Burkina Faso.” French troops have been dispersed across Beninese camps “to direct military operations and intelligence,” while officially masquerading as “instructors,” Noudjenoume explained.

“The objective” of such dispersal “is clear: to conceal the presence of French forces, whose previous concentration in military bases inflamed local patriotic sentiments, by making them less visible,” reads PCB’s statement.

This posture has allowed Benin’s President Patrice Talon to claim that there are no French military bases hosted in the country. “While technically true—there are no autonomous French military camps—the reality is different,” the statement added. French military personnel, in collaboration with the European Union, are not only training and equipping the Beninese military but are also directing its ostensible counter-terror operations.

AES countries, on the other hand, have accused France of using such border bases in Benin and Ivory Coast to support terror operations aimed at destabilizing its popular governments that ordered French troops out.

Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger are “closely monitoring the deceptive maneuvers initiated by the French junta, which pretends to close its military bases in certain African countries, only to replace them with less visible mechanisms that pursue the same neocolonial ambitions,” the AES said in a statement in December 2024.

‘France Itself Has Engineered Its Retreat’

This statement followed the announcement of French troops’ withdrawal by Chad’s government in late November 2024, soon after Senegal’s president indicated in interviews that the continued presence of French troops was unacceptable.

However, unlike Senegal, Chad is not ruled by a Pan-Africanist movement-backed leader who came to power by defeating a France-backed incumbent in an election. Chad’s President Mahamat Déby is a second-generation French loyalist, whose military coup to inherit power after his dictator father’s death in April 2021 was backed by France.

Repressing anti-French protests with massacres, mass arrests, and custodial torture, Déby has since maintained his power through brute force.

With his main opponent from the Socialist Party Without Borders (PSF) being gunned down by his security forces and other serious opposition candidates being barred from contesting the election, Déby won the presidential election in May 2024, with his own prime minister playing the opposition candidate.

However, his grip on power had become increasingly insecure, with mass protests aching to break out again at the slightest opening of democratic space, amid murmurs of discontented sections of the army ready to back the anti-France protest movement against Déby.

His government’s announcement of French troops’ withdrawal in this backdrop was met with skepticism, despite affirming, unlike in the case of Ivory Coast, that it had scrapped its military agreement with France.

“All the African governments that have successfully expelled French troops from their territories have popular support, unlike Chad, where the people have endured unprecedented repression under Déby’s rule backed by France,” PSF’s Ramadan Fatallah told Peoples Dispatch.

Other sections of the anti-French movement who initially believed in the slightest credibility of the announcement by Déby’s government are also now increasingly skeptical.

Mahamat Abdraman, secretary general of the Rally for Justice and Equality of the Chadians (RAJET), said that “France itself has engineered its retreat” from Chad. It has “adopted a new method of colonization,” requiring a smaller presence of its troops while embedding itself within African militaries and government. Déby’s security adviser and former director of his political police, along with his foreign minister and two of his wives, are all French nationals, he pointed out.

While continuing to exercise control through subtler means, France is “orchestrating” a formal withdrawal from Chad. Such a posture will allow it to deny responsibility for more domestic atrocities Déby’s regime may commit in the future and evade being openly implicated in any acts it may undertake to destabilize neighboring Niger at France’s behest, Abdraman told Peoples Dispatch.

The fact that France is compelled to cover up its tracks in the region with such maneuvers is a testimony to the “weakening” of its neocolonial power, said Ekissi. And “no amount of imperialist maneuvering can halt the inevitable collapse of French colonialism in Africa,” PCB’s statement concluded.

(Courtesy: Globetrotter, a project of Independent Media Institute, a nonprofit organization that educates the public through a diverse array of independent media projects and programs.)

❈ ❈ ❈

Sahel Alliance Unveils New Flag as Regional Bloc Moves Toward Greater Integration

Nicholas Mwangi

The Alliance of Sahel States (AES), that includes Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, has taken another decisive step toward regional integration following its recent withdrawal from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). On February 22, the new flag was unveiled and symbolizes the bloc’s growing autonomy as it seeks to redefine its political, economic, and security structures outside the influence of French imperialism and Western neoliberal frameworks.

The new flag showcases the AES logo: an orange sun radiating over a sturdy baobab tree. Beneath the tree, a group of silhouetted figures gathers, symbolizing unity. The flag also features an outline of the three combined AES territories, now presented without the borders that once separated them. Set against a green background, the design represents growth, hope, diversity, and renewal—reflecting both the promise of the alliance’s future and the vast natural resources of its member nations.

The alliance, formed in September 2023, has prioritized breaking away from long-standing colonial-era ties and creating a self-sufficient regional entity. In addition to unveiling a new flag, the three Sahelian nations have introduced measures aimed at deepening integration. They launched a Sahel-wide passport system and established a joint military force to deepen military coordination in order to combat jihadist insurgencies linked to Al-Qaeda and ISIS-affiliated groups, which have destabilized the Sahel region for over a decade. Joint military operations have been launched along their borders, focusing on disrupting terrorist networks and protecting civilians.

The decision to exit ECOWAS, announced in January 2024, was framed as a necessary move to counter what the AES states described as the regional bloc’s failure to respect their sovereignty. In recent years, ECOWAS imposed sanctions and restrictions on Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso in response to popular military takeovers in each country. However, the AES governments argue that ECOWAS policies were dictated by Western interests, particularly France, which has historically maintained economic and military control over West African nations.

Following their departure from ECOWAS, the AES states have also outlined plans to establish a single currency, further consolidating economic independence. This move is seen as an effort to reduce reliance on the West African CFA franc, a currency that has long been tied to the French Treasury and has been criticized for perpetuating economic dependency.

Dismantling colonial legacy

The Sahel alliance has actively engaged in decolonization efforts, both symbolic and structural. In Burkina Faso, the government has removed British and French-style judicial wigs traditionally worn by judges, marking a break from colonial judicial norms. Across the three nations, colonial-era monuments and street names are being replaced with symbols that reflect indigenous heritage and anti-colonial resistance.

Moreover, military agreements with France have been terminated. French troops were expelled from Mali in 2022 and later from Burkina Faso and Niger, following widespread protests against France’s military presence and accusations that it was exacerbating instability rather than addressing security concerns.

The AES’s push for self-reliance continues amid heightened geopolitical shifts in Africa, where many nations are reconsidering their alliances and economic models. The trio’s bold moves have drawn popular support as many on the continent hail them as a necessary assertion of sovereignty and a model for other African nations seeking autonomy and Pan-Africanist aspirations across the continent.

(Courtesy: People’s Dispatch, an international media organization with the mission of highlighting voices from people’s movements and organizations across the globe.)

❈ ❈ ❈

Canada Suffers Economic Losses as Burkina Faso Nationalises Land, Revokes Mining Permits

Marthad Shingiro Umucyaba

Canada is set to take economic losses as Burkina Faso and the Alliance of Sahel States, aka AES (Alliance des Etats de Sahel) introduce new measures to end neo-colonialism in Northwestern Africa. Burkina Faso, in particular, has introduced a new land nationalisation law under the Ibrahim Traore-led military government that will establish the whole land of Burkina Faso as state property. They will also be revoking mining permits to foreign, mainly western countries, and seizing state ownership over said resources.

Despite Canadian efforts, previously covered by The Canada Files, to limit the effects of the anti-colonial uprising of the AES on Canada’s colonial possessions in Africa, grassroots movements such as Waylyan aka Citizen’s Nightwatch, akin to the mobilisation movements in Cuba, have thus far thwarted the attempt by NATO-based NGOs to undermine the government’s anti-colonial actions.

The Canada Files spoke with Inemesit Richardson, an All African People’s Revolutionary Party member, the President of the Thomas Sankara Center for African Liberation and Unity (aka Burkina Books) and an African Stream journalist. Richardson detailed the impacts of the land nationalisation and the revocation of mining permits on Canada’s mining operations in Burkina Faso. She also explained the overall sentiment of the population in the AES and especially Burkina Faso towards the Traore government, and how that popular support has manifested itself in Waylyan.

Burkina Faso’s Land Nationalisation

On February 5, Burkina Faso’s Minister of the Economy and Finances, Abubakr Nacanabo, publicly released the policy of comprehensive land nationalisation, declaring that all of Burkina Faso’s land will be in the hands of the state. The Ministry has also forbidden foreigners from holding rural title deeds for land lease.

The program largely targets the dangerous mass purchase of farmland by private billionaires and companies like Bill Gates, who currently owns 242,000 acres of US farmland. and US and NATO member country holding companies in Ukraine that currently hold over 2,000,000 hectares worth of land lease titles. Land nationalisation and the prohibition on foreign owned rural land leases is also geared to support local food production and make the cost of local food production lower.

According to Richardson, while a popular measure, in terms of Canadian interests – which aren’t in rural land or real estate, but primarily mining – the land nationalisation policy will have a minimal impact on Canada’s operations in Burkina Faso. However, revocation of mining permits has already directly affected Canadian mining interests, and some of the mining permits that were revoked were Canadian based companies due to outrageous abuses.

Burkina Faso’s Revocation of Mining Permits

Shortly before Ibrahim Traore took power in Burkina Faso in September 2022, in April of that same year, a Canadian company came under fire. Two executives of the Perkoa mine, owned and operated by Canadian mining company Trevali, received a suspended sentence of 24 months and 12 months respectively for manslaughter after eight workers were killed due to negligence in safety protocols. The slap on the wrist ‘convictions’ were endemic of the neo-colonial government that was in place at the time. After Ibrahim Traore seized power, the Perkoa mine was liquidated and nationalised and the mining permit of Trevali was revoked.

According to Richardson, Traore also signalled that he will be revoking even more mining permits, back in October 2024. In 2023, there were 15 Canadian-based mining companies in Burkina Faso and all of their mining permits are at risk. This prompted Canada to pump millions of dollars into “women’s rights” initiatives throughout the AES, especially in Burkina Faso. The country was a noted cash cow for Canada which, by the government’s own admission, was at $1.6 billion dollars in private investment before the military coup and has since been reduced to $1.1 billion, a net loss of $500 million.

Canada is also notably still involved in allegedly supporting the Wahhabi terrorists fighting the AES. Canada still supports airlifts for the French military through Operation PRESENCE. The French military, according to Richardson, was accused regularly by the population and even the Mali government of supporting and arming the Wahhabi terrorists.

Sentiments around the new government

According to Richardson, the main reason that the NATO axis has failed to destablize Burkina Faso is the population’s formation of mass mobilisation movements in defence of the Traore government, whenever a colour revolution is initiated. The most notable movement is called the Citizen’s Nightwatch (La Veille Citoyenne) or Wayiyan.

Groups regularly monitor the country on rotation throughout the day and night for any colour revolution activities currently being financed by NATO states and Canada, in particular. In November 2024, they recently went on an exchange to Cuba to draw lessons from the Communist Party of Cuba’s mass mobilisation strategies and have gained even more experience, thus further weakening any prospect of a successful colour revolution against the Traore government.

Neo-colonial mining: a NATO project nearing its end

According to Inemesit Richardson, African Stream Reporter and President of Burkina Books, “The foreign policy in general and what the leaders [of the AES] have said many times is that they’re happy to work with any country around the world so long as that country is willing to respect the sovereignty and self-determination of the AES countries. They have stated that they will not collaborate with any countries that violate the sovereignty of the AES states. And so, in general they have preferred partnerships with countries like Russia, Iran, China to some extent… some south-south cooperation… with Venezuela, Nicaragua… they will slam that door shut, they will not collaborate with countries that violate their sovereignty.”

The NATO project of resource plunder in Northwestern Africa has reached its finale. The show is over, and no encore will be entertained by the audience, regardless of the “shows” proposed, such as Trump granting permission to AFRICOM to carpet bomb and carry out commando assassinations, Canada’s “feminist” foreign policy, the support of Wahhabism, or other obscene NATO initiatives.

NATO could fail in Northwestern Africa and has a very limited chance to stem the tide of revolutionary change throughout the continent as a whole. Canada’s $1.1 billion in Burkina Faso, and investment in other parts of Africa, will collapse, unless Canada can replace predatory exploitation with something the population, which is rapidly improving in education and consciousness, is willing to accept, such as the trading of a finished good for a finished good.

This in turn will lead to problems at home because Canada will be unable to trickle down shares of its plunder to the masses. Tent cities have already been normalised and teenagers are being conditioned into abandoning the idea of owning a home and instead renting at high prices.

The chickens, which began with the massacre of the Indigenous nations and continued with Canada casting its lot with the Nazi-led white supremacist and anti-communist NATO alliance, are coming home to roost. The inner conflict that is to come in Canada will not be pretty.

(Marthad Shingiro Umucyaba (formerly referred to as Christian Shingiro) is a Rwandan-born naturalized Canadian expat. He is known for his participation in anti-imperialist national and international politics and is the radio show host of The Socially Radical Guitarist. Courtesy: The Canada Files, Canada’s only news outlet focused on Canadian foreign policy. It has provided critical investigations & analysis on Canadian foreign policy since 2019.)