When a government with an established notoriety for its divisive, communal policies proposes scrubbing school textbooks of fundamental chapters on secularism, federalism, nationalism, citizenship and human rights, it is a cause for alarm for more than just students.

It should make everyone look at this sustained effort to foster a deliberate historical amnesia as one that would enable an education policy which conveniently fits in with an ideology’s particularly communal view of Indian history. This is what the government of Karnataka appears to be doing with its July 27, 2020 decision to remove chapters on the salient features of the Indian Constitution, the Mughals, Hyder Ali, Tipu Sultan and the teachings of Prophet Muhammed and Jesus Christ.

Tipu Sultan (1750-1799), as a political icon, has been equally exploited and claimed by both the present government and the opposition. While the Bharatiya Janta Party portrays the former ruler of Mysore as a cruel, religious bigot who effected several forced conversions (which were only used by Tipu as a political tool in newly acquired territories, and not necessarily as means to a religious end), the Congress chooses to see him as a secular, anti-colonial nationalist.

And yet, a careful reading of manuscripts housed in the myriad archival repositories of Versailles and Paris concerning the 1788 embassy he sent to the French king, Louis XVI (1754-1793), indicates that Tipu was neither of these two categorical, binary labels. To the 18th century diplomatic mind, he was a deserving statesman who understood the political and diplomatic exigencies of his time, and whose policies had widespread, international ramifications.

Hyder Ali ‘spanked the English’

The animosity Hyder Ali (1720-1782) and his son Tipu Sultan had for the British is well known, and so is the fact that they sought alliances with the French to contain the growing political influence of the British in late 18th century India. What is less studied, though, is the manner in which such alliances nourished by the French since the 1760s played out in French discourses on empire.

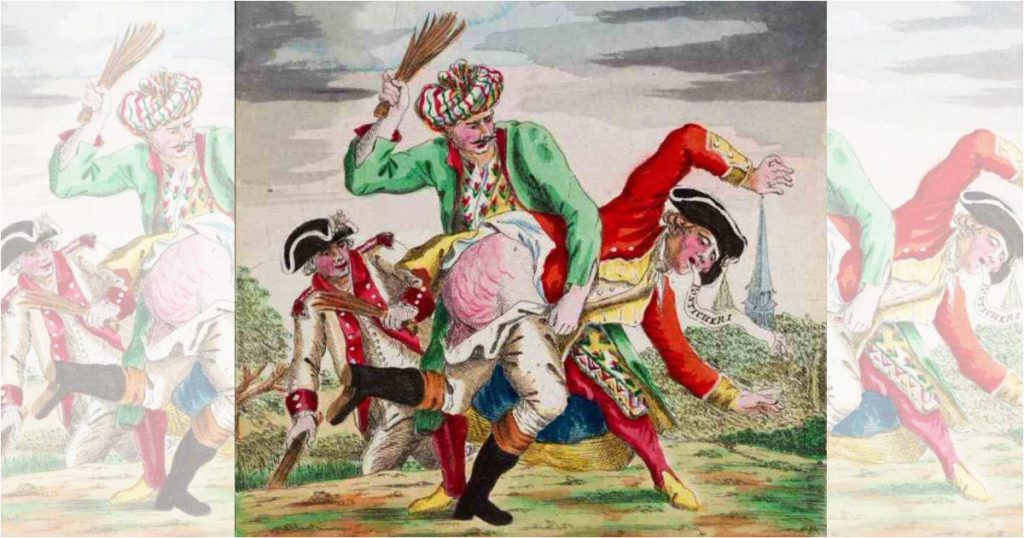

Sometime in 1783, a pamphlet bearing a hand coloured engraving appeared in the political circles of Paris. In a somewhat celebratory pamphlet, French engraver Antoine Borel (1743-1810) had taken a jibe at the British defeat in the Second Anglo-Mysore War (1778-1784) by depicting Hyder Ali spanking the exposed bottoms of an English officer while he coughed up a piece of paper with “Ponticheri” written on it. From the background a soldier of the French East India Company could be seen providing Hyder Ali with sticks. The caption – translated to “Hyder Ali spanking the English; a French soldier provides him with the sticks” – was an evident allusion to the times when French troops from Pondicherry joined Mysore’s forces in fighting the English during the Second Anglo-Mysore War. For the French, this alliance was an opportunity to avenge the English sieges of the French trading posts in India during the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763) and the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783).

Borel’s caricature is not only an archetypal French reading of the relationship between Mysore, France and England, but also illustrates the French imaginaries that developed around these events.

In the “lutte pour l’Inde” – the two European powers’ great fight for India – the French had lost out by 1750s and 1760s. Versailles reconciled to a general policy of retreat from India after sending expeditionary troops to Mysore to fight the English during the American Revolutionary War. There were also rumours that French admiral Pierre André de Suffren de Saint Tropez, bailli de Suffren (1729- 1788) had met Hyder Ali in 1782 about a possible coalition.

But, after that, France’s engagement with “l’Inde perdue” – an India lost to the English – takes a curious turn. Annoyed at England’s growing sphere of influence not only in India and but also in the affairs of Europe, and newly armed with the values of French Enlightenment, certain commercial and philosophical circles in Paris believed that it was necessary for France to take up, in the near future, the role of the “liberators of Indoustan”. “A methodical tyranny [of the English] has succeeded the arbitrary authority of the nawabs,” wrote Denis Diderot (1713-1784) and Guillaume Thomas Raynal (1713-1796) in Histoire philosophique et politique des établissements et du commerce des Européens dans les deux Indes (1770). To oust the British, Pierre-Louis Moline (1739-1820) suggested allying with Indian princes “who are but waiting for an opportunity to liberate themselves from British domination”.

Throughout the 1770s and 1780s, the archetype of such an Indian prince in the French imaginaire was “the celebrated Sultan of Mysore, Hyder Ali, who has already expressed, through his victories, his hatred towards the English”. While English sources of the time struggle to find words harsh enough to portray him as the epitome of oriental despotism, French accounts depict “Hyder-ali-can, nabab de Mayssour” as “the prince who is a formidable enemy of the English, against whom he waged several wars” – in short, a “Great Man”.

Strategic diplomatic considerations

Tipu was furious when he heard that Louis XVI had signed a peace accord that provisioned French disengagement from India in favour of British interests. Nevertheless, when the French king sent a diplomat of the French East India Company to re-establish relations, specifically commercial ties, Tipu readily agreed. A partnership like that suited his vision of Mysore as a global economic giant, and it gave him another chance to convince the French into an anti-British alliance. By 1786, Tipu began planning an embassy to the French court – the purpose was to ask the French king for engineers, gardeners, artisans and manufacturers of glassware, clocks, porcelain and weapons, in addition to renewing proposals for a potential Franco-Indian alliance.

Neither Louis XVI nor anyone in his court was aware of Tipu’s embassy till the time the ambassadors set off from India. It was only on July 21, 1787, that David Charpentier de Cossigny (1740-1801), the then Governor General of French India, wrote to France of the “departure of the ambassadors of Tippoo Sultan from Pondicherry… The first two ambassadors, Mahomet Durvesh-Kan and Archiolly Kan (sic), are people of little intellect and are proud. The third, Mohamet Ousman-Kan, is more knowledgeable and the only one with whom we can talk about our respective interests. Moreover, the three ambassadors do not get along well with each other.”

Louis XVI and his aides were stupefied by the news and not sure how to receive the embassy – one major reason for this was the peace accord with England, and another was the widespread dissent mounting against the monarchy. In another dispatch to France, Cossigny wrote: “I still believe that the intentions of Nabab Tippoo Sultan is to offer, through his ambassadors, a just tribute of respect and admiration to His Majesty. My opinion is that any alliance that the Prince will have proposed must be referred to the circumstances… the court of France must not engage itself in a manner whereby it would be obliged to participate in all the quarrels that Tippoo Sultan and the English pick up – it would mean putting ourselves in the position of mistreating him for a second time – which would be of very bad consequences, including estranging his mind against the French forever.”

Realising the profundity of the situation, Louis XVI and his ministers decided to welcome Tipu’s embassy to talk about mutual commercial interests. Though the possibility of a military alliance was remote, merely welcoming the ambassadors, it was thought, could unnerve the English and have far-reaching repercussions on imperial European politics. Relations between France and Mysore had to appear “more important than it actually is,” wrote one of Louis’s advisors.

A sensation in Paris

The embassy – “three with the title of ambassador, with interpreters and forty people in the entourage” – debarked in the French port city of Toulon in June 1788. On July 16, less than a year before the French Revolution, they reached the French capital to an incredible welcome.

Hardly had a free man from the celebrated realm of Tippoo Saëb, or for that matter from India, been seen on metropolitan French soil before – and they were an instant sensation in the high social and commercial circles of Paris. Moreover, the embassy was rumoured to be carrying, as gifts from Mysore, “three tonnes of diamonds that will be spread through the Hall of Mirrors up to the Salon of Hercules” – “while some of them are the size of pigeon eggs, the smaller ones are the size of hazelnuts”!

A frenzy broke out among Parisians – the ambassadors were seen in the poshest quarters of Paris and crowds followed them everywhere for a closer look. The kind of oriental imagery that developed around the ambassadors can be pictured from a popular print that went up for sale shortly after their arrival in the French capital. Developed from an engraving, and titled “Ambassadors of Tippoo Saëb, sovereign in India and successor of the famous Heyder-Aly-Kan”, the print dwells on a host of historical misrepresentations. Tipu is seen with a beard, a physique, and clothing that seem more Turkish than Indian. On the bottom side are seen two men, again supposedly Indian, holding a string of pearls over a fleur-de-lis shield, representative of the Bourbon monarchy. The print was an immediate hit.

Prints were not the only thing that commercial circles in Paris explored to exploit the frenzy. The Journal de Paris reported almost daily on the whereabouts of the three ambassadors, often publishing detailed accounts of their quotidian schedules. Organisers invited the ambassadors to the fanciest operas, musicals and firework spectacles and promptly advertised in the Journal de Paris – “Their Excellencies, the ambassadors of Tippoo Sultan will honour this spectacle with their presence” – as a convenient way of attracting a decent crowd. Several books and translations from English dedicated to Hyder Ali, Tippoo Saëb and the French court’s proceedings with the embassy were published, republished and advertised in the Journal. A French fashion journal, Magasin des modes nouvelles françaises et anglaises, proposed more dresses à l’indiennne in general, and curiously, one à la Tipu Sahib. People rushed to the shops under the arcades of the Palais-Royal to buy for a livre a print by Charles-François-Gabriel Le Vachez that depicted the ambassadors being received by relatives of the royal family.

Gabriel Le Vachez’s print became, in ways, the sole representation of the interaction between the ambassadors and members of the royal family since an official illustration commemorating the event was never commissioned. Another established protocol was broken when Tipu’s gifts of cotton muslin robes and pearl and diamond jewellery were never exhibited because they were taken to be far below what was expected (by the contemporaneous European mind dwelling on abstract imagined notions of oriental luxury). There had been an expectation of gifts “worth millions” and it was feared that the reality will encourage “innumerable jokes in the foreign journals, particularly in the English press”. As importantly, no formal report was released elucidating the details of the king’s audience to the ambassadors and their negotiations. The embassy was, in the end, sent off with some of the artisans Tipu had requested, a few of whom would later help build the reputed Tipu’s tiger.

Elaborate portraits of the first two ambassadors were painted, however, thanks to Marie Antoinette’s portraitist, Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842). Of them, the first still exists. She later reminisced, “In 1788, ambassadors were sent to Paris by Emperor Tippoo-Saëb. I saw these Indians at the Opera, and they seemed to me so extraordinarily picturesque that I wanted to paint their portraits. Having communicated my desire to their interpreter, I knew that they would never consent to be painted if the request did not come from the King, hence, I obtained this favour from His Majesty.” While the ambassadors were sailing back to Mysore, without the Franco-Mysorean alliance that Tipu had so desperately hoped for, their portraits were chosen to be exhibited at the prestigious 1789 Salon of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture.

Looking back at all the diplomatic endeavours the mis-portrayed ruler of Mysore put in to keep the British at bay, despite all odds, one cannot help but wonder if any of our current political leaders have the legitimacy to attempt effacing Tippoo Saëb from the registers of public memory.

(Arghya Bose is an author and a doctoral researcher of political sciences at the Centre d’Études de l’Inde et de l’Asie du Sud, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (Paris).

The author has consulted archives at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Archives nationales de France, Centre des Archives diplomatiques du ministère des Affaires étrangères [Archives of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs] and the Archives départementales des Yvelines for the sources quoted in this article. The author is also grateful to, among others, Jacques Weber, professor emeritus, Department of History, Université de Nantes, and Meredith Martin, associate professor of Art History, Department of Art History, and Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, for their extensive primary research from which this article draws considerably. Article courtesy: Scroll.in.)