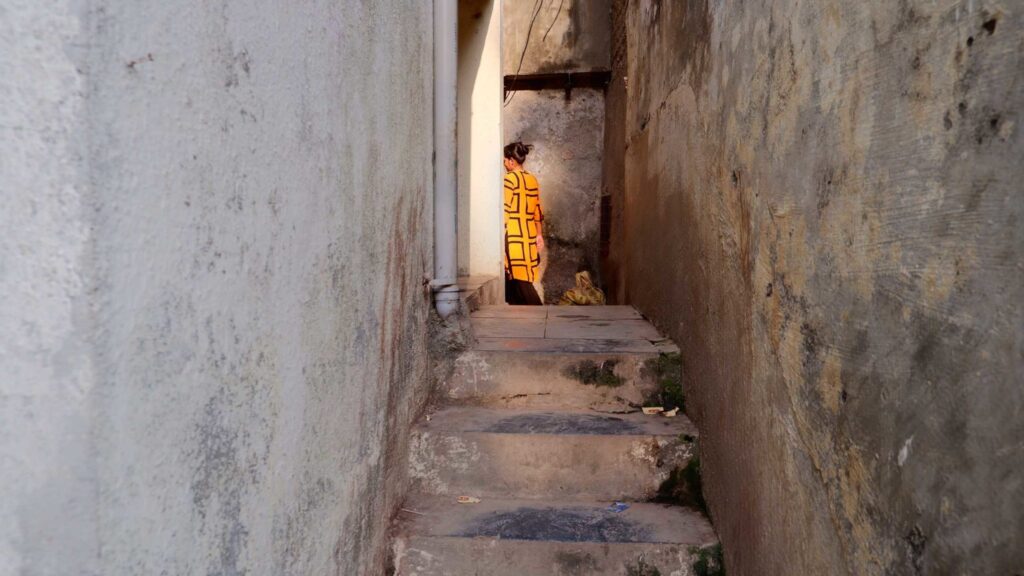

On a humid afternoon in May, a handful of local residents gathered at a one-room home in an unplanned housing settlement in Mumbai. The women greeted each other and then sat down on the small porch and on the tiled floor inside, swapping stories about the day’s events through the doorframe. Their conversation was lighthearted until someone mentioned hydration and the mood changed. “We won’t be consuming any more liquids today,” said 31-year-old Kalawati Yadav. “If we do, we might have the urge to urinate by later in the evening.” By then, the public toilets would be filthy from the day’s use, and without lighting, they would also be dark. “It’s not a safe time to go,” Yadav said.

Daytime is not much better, though, because the facilities are rarely truly clean. According to the women, the public toilets are usually dirty, unlit, and lacking in water. They are also in short supply. Two facilities, each with a dozen toilets — six for women and six for men — service the entire settlement, Subhash Nagar, which covers about one tenth of a square mile and as of 2020 housed more than 9,000 people. The municipal government is supposed to be responsible for sanitation, but there is very little oversight. (City officials did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

As a result, for residents of Subhash Nagar, and for millions of low-income residents across India, bathroom schedules are often dictated not by biological need, but by inadequate toilet infrastructure. Several women told Undark that they routinely hold their urine and avoid drinking liquids in an effort to reduce trips to the facilities. These behaviors lead to stomach aches and constipation, but the women said they don’t have better options. Their neighborhood was unplanned — starting as a collection of tin plank homes, which were later replaced with concrete structures — so the houses are not connected to septic tanks. There are no private toilets, and the owners cannot afford to regularly use the fee-based facilities in other parts of the city.

This predicament is part of a larger story of India’s efforts to bring affordable and sanitary toilets to its population of 1.4 billion people. According to The Hindu, an Indian daily newspaper, nearly half of all Indians practiced open defecation as recently as 2013, with people going outside in fields, bodies of water, or other open spaces. Without public sanitation — septic tanks in particular, but also water and cleaning products — pathogens spread readily, causing serious health problems. The U.N. Deputy Secretary-General has called for the elimination of open defecation, and in 2014, Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched Swachh Bharat Abhiyan, or Clean India Mission, an effort that led to the construction of over 100 million toilets. Today, according to the World Bank, just 15 percent of the population practices open defecation.

Having new public toilets “is a step forward,” wrote Sarita Vijay Panchang, a public health researcher who did her 2019 dissertation on India’s urban sanitation, in an email to Undark. But many of India’s public toilets are overcrowded, she noted. This leads to long lines, sewage overflows, and concerns about personal safety — all of which constitute their own set of public health problems.

Surveys show that the situation is especially acute in urban areas like Mumbai. Safety concerns, as well as cultural norms, deter women from practicing open defecation as a fallback. (Men are more likely than women to practice open defecation even when public toilets are available.) Physicians and activists say the continued practice of caste- and class-based discrimination compounds the harms, as some women are forbidden from using the toilets in their workplaces.

“The ceiling plaster has fallen on me once,” said Ambika Kalshetty, the gathering’s 35-year-old host, who works as a housemaid in the nearby high-rise apartments. The men’s toilets were built atop the women’s toilets, she explained, and the men’s “leak on us at times — it’s disgusting.” She said she really doesn’t feel good until she returns home and cleans thoroughly with soap and an anti-septic.

Another woman, Sangeeta Pandey, recalled watching a pregnant woman faint while waiting in a long line for the community toilets. “It was humiliating,” Pandey said, “but also, what could she do?”

Local activists have worked to raise awareness and bring improvements. Still, the women gathered in Kalshetty’s home say that change is slow, and for now, they are on their own to manage a difficult situation.

**

Several years ago, researchers surveyed more than 600 women across 33 slums in Maharashtra, the Indian state that includes Mumbai. They found that among those without proper toilet access, more than 21 percent reported holding in their urine and more than 26 percent said they modify their meals to avoid using the toilets at night. These findings are supported by Panchang’s research in the region, which also found that women avoid urination and defecation when they perceive their community toilets to be unsafe.

Such behavioral changes can lead to negative health effects, said Suchitra Dalvie, a Mumbai-based gynecologist and women’s health activist. Frequent urination helps flush any bacteria, thus reducing risk of urinary tract infections. (The women in Subash Nagar said that they regularly experienced UTIs, some as often as every few months.)

Even the relatively well-off are affected. Dalvie recalled a conversation with the state’s former minister of health, a young woman who often needed to travel for work. The health minister would limit her water intake, knowing that the public toilets she would encounter on the road might not be adequate. This is an example of how women’s problems have been normalized in India, said Dalvie.

Toilet infrastructure is not just an issue of sanitation, said Deepa Pawar, a social activist focusing on gender and youth issues in marginalized communities. “It is a much larger problem that encompasses health, gender, and social justice issues,” she said.

Pawar’s organization, Anubhuti, conducted several toilet audits across Mumbai in 2017. Their audit of the K/East Ward, a municipal district that includes Subhash Nagar, found conditions similar those Undark reported: damaged toilets, lack of water, and inadequate cleaning services. And while the central government has called for one commode per 30 individuals, the audit found far fewer.

Pawar grew up in Mumbai’s low-income neighborhoods, so the issue is personal. “When you use your toilet at home, there is no struggle involved,” she said. But in using public toilets, one must contend with an array of concerns.

The problems were aggravated during the Covid lockdowns, Pawar said, when many of the city’s free public toilets were closed. “They only kept the pay-and-use toilets functional. From where will the poor get the money to use these toilets if they are not allowed to work?” she asked. The closures particularly affected the nomadic communities that comprise nearly 10 percent of India’s population. These are communities that traditionally moved around, and while many have now settled, they are economically weak and face discrimination.

Women and men in Subhash Nagar were also forbidden from using the toilets during the lockdowns, but they said they used them anyway. And across Mumbai, many men simply defecated outside. Although the city government ordered toilet fees to be waived for everyone, Pawar and residents of Subhash Nagar say that in practice, women were still charged. “Essentially women were being penalized for their gender while men were being given a free pass,” Pawar said.

As a member of a nomadic tribe, Pawar is intimately familiar with the social dynamics that prevent some women from accessing basic services like toilets. “During our campaigns, we question local officials about the disparity in access to toilets for members of nomadic tribes likes ourselves, and they often respond by asking us why we don’t use the free public toilets in malls instead,” she said.

The reality is that those spaces cater to the middle and upper class, and people of lower socioeconomic status are not welcome there. “Will a female laborer with a bullock cart be allowed to enter a mall? Has our society inspired such courtesies among those who work at and visit these malls to allow nomadic laborers within their complex?” she asked rhetorically.

Mumbai is a large commercial city that relies on the labor of women and of marginalized communities, said Dalvie. Businesses, government, and wealthy residents should therefore “accommodate the conveniences” of everyone.

Going forward, Panchang would like to see India strive to build more in-house toilets that are connected to sewers. Residents will be able to maintain them well, and women will not have to pay such a heavy price for the country’s efforts to eliminate open defecation. “Public toilets,” she wrote in her email, “are not a substitute for household toilets.”

(Ruchi Kumar is an independent journalist reporting on South Asia. She has been published in Foreign Policy, The Guardian, NPR, The National, Al Jazeera, and The Washington Post, among other outlets. Courtesy: Undark Magazine, a non-profit, editorially independent digital magazine exploring the intersection of science and society. It is headquartered in Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.)