Iain Bruce, 5 June 2020

Last week, Brazil moved into second place in the world league table of Covid-19 cases with almost 375,000 confirmed infections – 12,000 more than Russia. The World Health Organization said Latin America was emerging as a new epicentre of the pandemic. Other counts give Chile the highest number of cases per capita, and Ecuador the highest death rate per capita. Peru and Mexico are also on a sharp curve upwards.

We know all of these comparisons are flawed, based on varying and inadequate levels of testing. A study by the University of Pelotas in southern Brazil, based on interviews and tests carried out through the third week of May, indicated that the real number of people infected across the country was probably seven times the officially confirmed figure. Yet the intensity of the conflict over Coronavirus in several Latin American countries is now unparalleled.

Some of the political narrative is familiar, if more extreme. In Brazil, a blustering, right-wing populist leader (some would call him a neo-fascist), along with his coterie of far-right, conspiracy-theorist advisers and ministers, is under fire from the conservative establishment and traditional media for openly flouting and undermining lockdown restrictions, as well as for trying to appoint a family friend to head the Federal Police in order to protect his sons from being investigated over their possible involvement in the murder of a radical left councilwoman and gay rights campaigner, Marielle Franco, in 2018. Over the weekend, it came close to a coup.

The soldier in charge of President Jair Bolsonaro’s security cabinet, General Augusto Heleno, threatened the Supreme Court with grave, but unspecified, consequences if it went ahead and investigated the president’s mobile phone records. In response, the Court published a much commented-upon video of Bolsonaro and his education minister swearing at the court and threatening to lock up the judges if he didn’t get his way.

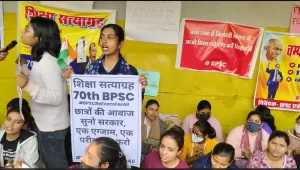

But there is another difference, which the international media have barely reported; the level of resistance from the Left. For all the indignation of Brazil’s traditional liberals and conservatives, it is members of congress from the Left – from the Party of Socialism and Liberty (PSOL) and the Workers’ Party (PT) – who have taken the lead in launching a demand for the impeachment of President Bolsonaro. 400 social movements backed the move. Similar action is now being taken against the education minister and General Heleno for their additional threats to Brazil’s democratic institutions. All these actions build on the momentum of daily pot-banging protests by tens of thousands of Brazilians from their doors, windows and balconies against the government’s response to the pandemic.

In Chile and Ecuador, two countries that saw huge strikes and protests against neoliberal policies from last October, social movements have, literally, taken a step further.

The protests in Chile never completely stopped. In recent days, they have gathered pace again in the working-class neighbourhoods of Santiago to demand more help for those suffering hunger as a result of the lockdown. In Ecuador’s capital, Quito, students held an initial march, with careful social distancing, on 5 May, after the government announced it would be cutting 10 per cent or more from the budgets of public universities, apparently in order to continue making payments on the country’s foreign debt. More protests followed; a court declared the cuts unconstitutional, and President Lenin Moreno partially backed down.

Nevertheless, days later, his government presented a series of new austerity measures: massive cuts in public spending, including 25 per cent reductions in hours and wages, the elimination of many employment rights and the privatization of half a dozen public companies, among them the post office and the national railway. Again, the aim was “to protect Ecuador’s access to international credit” – in other words pay its debt in line with its commitments to the International Monetary Fund.

Students, trade unions and other movements, including the main Indigenous movement, Conaie, warned that there could be “another October”, and called for a day of protests this last Monday. The day before, President Moreno’s state of the nation address to parliament was met with a barrage of pot-banging across the country. On Monday, thousands turned out in Quito and other cities, again with face masks and a careful distance between each protester. In fact, it was the police who did not respect social distancing, as they charged protesters in the historic centre of Quito, using tear gas and truncheons.

The role of Ecuador’s Indigenous movement will be key to the future of this movement – and that movement may have lessons for those around the world struggling to protest their governments in a time of quarantine.

(Courtesy: Sourcenews, an online journalism platform based in Scotland.)