The following is an excerpt from ‘Reading Gandhi in the Twenty-First Century’, by Niranjan Ramakrishnan (Palgrave Pivot, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

As I watch world events unfold, Gandhi’s life appears increasingly relevant. With each passing day, his words and methods seem even more uncannily prescient.

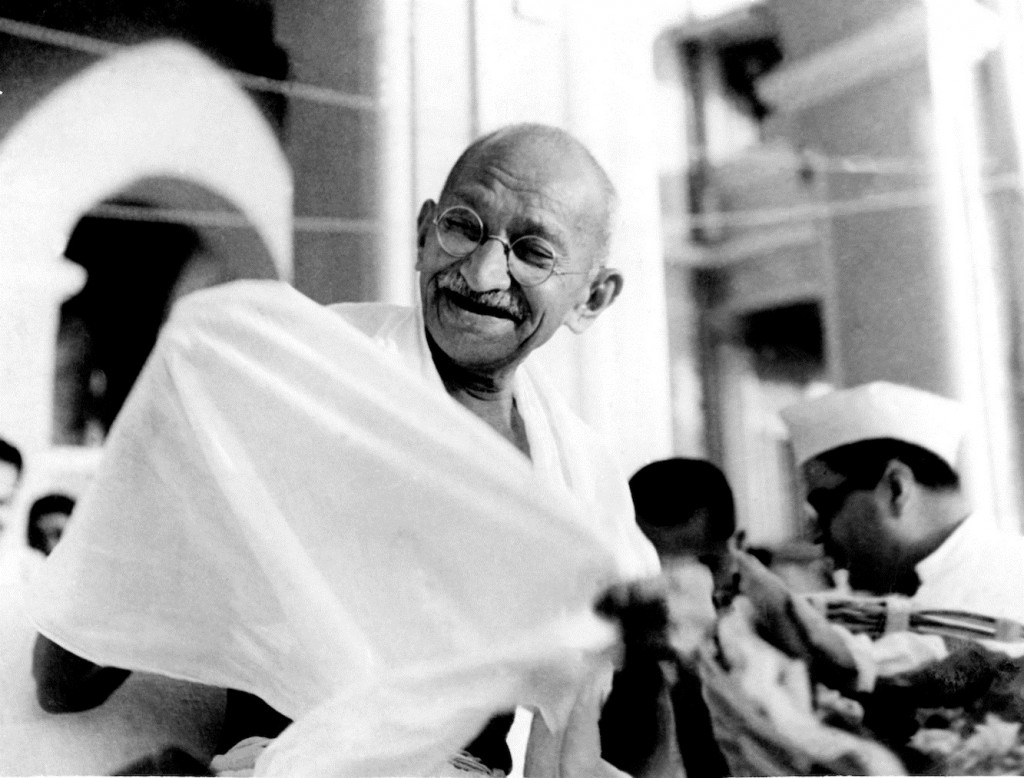

Gandhi had numerous interesting and formidable personal characteristics – prodigious courage both physical and political, enormous self-discipline, asceticism and industry (more than a hundred volumes of writings and twenty-hour days), a fine sense of humour, and the ability to laugh at himself – that must have played a major role in the making of the Mahatma. But if I were to condense his political philosophy into one phrase, it would be this: the freedom of the individual.

Complete liberty, for Gandhi, was the first and last goal. India’s freedom from Britain, to him, was only an objective along the path, and a rather insignificant one at that. Far more important was the ability of each individual to seek out his or her own freedom. “Real Swaraj (freedom) will come, not by the acquisition of authority by a few, but by the acquisition of the capacity by all to resist authority when abused,” he wrote. I think of this statement every time I recall how mutely the public of the United States accepted the slap delivered full to its face by the Rehnquist Supreme Court after the 2000 presidential elections, followed by the post-9/11 march of official arbitrariness and open violation of liberties.

It is also in the context of liberty that ahimsa, Gandhi’s creed of non-violence, must be understood. It was not out of some sense of piety that he espoused peaceful means. He held non-violence to be essential because it afforded the only democratic means of struggle. It was available to everyone – not just those who owned weapons. Second, a violent victory, even a just one, would prove only that violence had triumphed, not necessarily that justice had done so. A violent solution would mean that the fate of the unarmed many would be mortgaged to the benevolence of the armed few. This was contrary to liberty as Gandhi saw it.

An extremely intelligent man, he had a knack of cutting right through shibboleths to the heart of the matter. In an earlier echo of the American position on Iraq and Afghanistan, the British kept telling India that they would leave India in a heartbeat, if only they could be sure the country would not fall into anarchy. This made some sense to many in view of the vicissitudes and general caprice of feudal rule in pre-British India, for self-governance. When one hears the cant that passes for political discussion on our airwaves, how one longs for a similar voice today.

Gandhi saw that millions had lost their livelihood because the British, in a former era of globalisation, had systematically destroyed India’s cottage industries to create a market for the products of the Industrial Revolution. Gandhi was the chief architect of India’s revived cottage industry. Although this was a magnificent achievement in itself, even more telling was the way he brought it about. He did not run complaining to the British government, asking it to reduce exports to India. Instead, he mobilised people to buy Indian-made goods. Huge bonfires of foreign cloth resulted in the handspun Indian fabric khadi replacing foreign mill cloth to become, in Jawaharlal Nehru’s words, “the livery of India’s freedom.”

This too has to do with freedom. To have demanded something of the government would only have increased its power. Gandhi instead chose to empower each individual to make a statement by shedding foreign cloth and wearing khadi. Today, a third rail of American politics is the word “trade.” It is commonly accepted, and rarely challenged, that trade is a deity to be propitiated at all costs – even if doing so means sacrificing jobs, families, homes, even towns or entire ecologies. Gandhi wrote that he would like to see all of a community’s needs met from within a reasonable radius. Some years ago Vegetarian Times carried a mind-boggling statistic: the average item consumed in America travels 1200 miles. Is it any surprise we have to invade other countries for oil? As American gadflies such as Ralph Nader and Pat Buchanan rail against NAFTA and the WTO, one wonders why they haven’t thought of organising a movement to buy American-made products.

It is a paradox of our times that with the availability of the finest gadgetry and every form of material sustenance, the individual has seldom been more powerless or redundant. Gandhi’s perception has been proven right, in that the more a human being is regarded as an economic entity, the less he remains an individual.

The world, according to his view, was made up of individuals, and disfiguration of this structure could not but result in a distortion of the aggregate. Toward the end of his life, writing to his associate and heir, Jawaharlal Nehru, he says that “man should rest content with what are his real needs and become self-sufficient. If he does not have this control he cannot save himself. After all the world is made up of individuals just as it is the drops that constitute the ocean. This is a well-known truth.”

All the arguments…questioning the practicability of Gandhi’s ideas are true in a limited sense, some of them even obvious. The “obvious” is inertia’s customary resort against the trouble of changing for the wiser. I use the word “obvious”, too, because Gandhi can be classed with Galileo or even Einstein in the way he kept on challenging the conventional wisdom. As anyone originating a new paradigm must seem, Gandhi often appeared to be unrealistic, if not unreal. A man leading a population of 300 million facing a foreign ruler of infinitesimally smaller numbers declared that he would rather go without his country’s freedom than have it won by violent or deceitful means. A man who had guided his ancient land of freedom in a manner unprecedented in history chose to observe the day of independence not by whooping it up in the capital city, but by fasting half way across the continent to bring peace among rioting factions. A man whose intelligence and business acumen could have made him a top industrialist saw instead the depredation set in motion by industrialism and spoke out against it. There was nothing conventional about Gandhi, and the fundamental questions he raised will not be wished away by conventional wisdom.

A strange but striking tribute, though it never mentions Gandhi, appears in a recent article by Morris Berman. Called ‘The Wanting of the Modern Ages,’ it declares that the modern age and all that it connotes are at a dead end, and that what is called for is nothing short of a new “Civilisational Paradigm’. Berman might have added that one of the chapters in Hind Swaraj is titled ‘What is True Civilisation?’ The book was written in 1909. That the question was still exercising Gandhi twenty years later is evident from a quip attributed to him during his visit to England in 1931: asked by a reporter, “Mr. Gandhi, what do you think of modern civilisation?” he is said to have replied, “I think it would be a good idea.”

Albert Einstein propounded the General Theory of Relativity in 1915. It wasn’t until 1919 that it was actually verified. Gandhi declared modern civilisation unsustainable back in 1909. He was not making this argument because he was familiar with global warming, housing bubbles, or collateralised debt obligations. Instead, it was because he saw the Emperor’s new clothes for what they were. Modern civilisation based on heavy industry and centralisation required an ongoing bubble of consumers. It was debasing to all concerned, and life-destroying to millions. As Einstein’s theory was proved experimentally four years later at Principe, a century later we can see every element of Gandhi’s warnings coming true in fear-stricken populations and rudderless leaders trading away every vestige of human dignity for promises of safety and economic welfare. “We pretend to work and they pretend to pay us” went the old Soviet-era joke. “We have met the enemy, and he is us,” as Walt Kelly said.

Morris Berman notes in his article: “[V]ested interests, in both the economic and psychological sense, have every reason to maintain the status quo. And as I said, so does the man or woman in the street. What would our lives be without shopping, without the latest technological toy? Pretty empty, at least in the US. How awful, that capitalism has reduced human beings to this.”

This is exactly the erosion Gandhi had foreseen and warned against. In Gandhi’s view, this was one end result of an alienation from one’s sources of sustenance. “Outsourcing” the basics of one’s daily living would eventually lead to the loss of human dignity, to his mind the greatest tragedy imaginable.

But would a population busy figuring out the latest neat feature in one gadget when it wasn’t trying to get the best deal on the next have any patience with someone telling it to toss the whole darn thing into the ocean, as Gandhi once persuaded his associate Hermann Kallenbach to do with his expensive pair of binoculars?

The answer to “Where do we go from here?” lies in whether we are willing to abandon the conditioning of “a new excitement every minute” and pay attention to the nature of our own lives and of our surroundings. Gandhi had thought a great deal about the corrosive effect of constant thrill. “There is more to life than increasing its speed” is a quip often attributed to him. But he wrote at greater length about the essential nature of the mundane:

All natural and necessary work is easy. Only it requires constant practice to become perfect, and it needs plodding. Ability to plod is Swaraj. It is yoga. Nor need the reader be frightened of the monotony. Monotony is the law of nature. Look at the monotonous manner in which the sun rises. And imagine the catastrophe that would befall the universe, if the sun became capricious and went in for a variety of pastime. But there is monotony that sustains and monotony that kills. The monotony of necessary occupations is exhilarating and life-giving. An artist never tires of his art. A spinner who has mastered the art, will certainly be able to do sustained work without fatigue. There is music about the spindle, which the practiced spinner catches without fail. And when India has monotonously worked away at turning our Swaraj, she will have produced a thing of beauty, which will be a joy forever.

Would anyone today listen?

(Niranjan Ramakrishnan has been a long-time contributor to Counterpunch and Countercurrents and his work has been carried several newsportals around the world.)