Kanpur, Lucknow, Sitapur (Uttar Pradesh): Until 2017, Mohammad Shafiq and his family of 10 who live near the now defunct Colonelganj slaughterhouse in the heart of Kanpur city would have scraps of meat in their dinner almost every evening.

Shafiq made a living by purchasing offal or organ meat from the abattoir and selling this from a roadside stall. He could make a profit of Rs 400-Rs 500 everyday, and the leftovers ended up in their meals.

“Now we are only able to eat half a kilo of buffalo meat once a fortnight,” he said.

Since 2017, with all four animal slaughterhouses in Kanpur closed, among at least 150 abattoirs and slaughterhouses ordered shut across the state by the government of chief minister Yogi Adityanath in Uttar Pradesh (UP), Shafiq has sold churan (a tangy digestive) and candies from a cart.

“The income is not even half of what I used to make with meat,” said Shafiq.

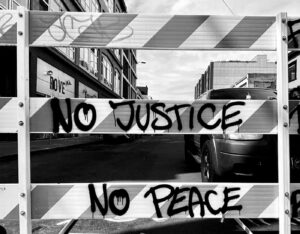

In April 2017, two months after assuming office, chief minister Adityanath ordered a state-wide closure of mechanised abattoirs, including government-run facilities, and “unauthorised” meat shops. It was his fulfilment of an election manifesto promise, a move met with protests and anxiety for thousands of families who made a living selling meat or processing animal bones, horns, fat and hair.

The UP government’s sweeping measures throttled the informal meat industry and its ancillary businesses. Since 2014-15, when cattle slaughter re-emerged as a divisive issue nationally with several states outlawing cow slaughter or enforcing existing bans on it, meat production in Uttar Pradesh, still India’s largest meat producing state, began to fall.

While other major meat-producing states witnessed a significant growth in the sector during the period from 2014-15 to 2019-20, annual meat production in UP fell from 1.3 million tonnes to 1.16 million tonnes. (In the same period, Maharashtra recorded a growth from 630,620 tonnes to 1.13 million tonnes; Andhra Pradesh from 527,680 tonnes to 850,390 tonnes and West Bengal from 657,170 to 902,860 tonnes.)

While much of this recorded meat production reflects data from export-oriented private units, on the ground, government-run slaughterhouses have remained shut, affecting thousands of small-scale meat sellers who were forced to quit the trade. Animal rearers in rural UP, finding livestock prices on the decline alongside rising fodder costs, have been forced to reduce their flocks or quit the field.

Despite a 2017 order of the Allahabad High Court to issue licences to slaughterhouses, most major cities in the state have not had a single authorised state-run abattoir for well over four years.

For the poor in UP, meat has all but disappeared from meals.

The biggest impact was on buffalo meat, consumed mostly by Muslims and an affordable source of animal protein and other nutrients. From Rs 140 per kg in 2017, its price has risen to Rs 240 per kg. Goat meat became twice as expensive between 2017 and 2021, from Rs 300 per kg to Rs 600 per kg.

Kanpur meat retailer Gufran Ahmad Chand said no more than 5% of the state’s butchers and meat dealers were still in business. “The rest are either selling vegetables, plying rickshaws or dealing in junk,” he said.

Abattoirs Shut, Plan for Modern Facilities Almost Abandoned

In 2015, hearing a plea against slaughterhouses operating without environmental clearances, the National Green Tribunal (NGT) ordered the closure of slaughterhouses in UP that violated pollution and hygiene norms.

Under The Prevention and Control of Pollution (Uniform Consent Procedure) Rules, 1999, slaughterhouses are listed in the ‘red’, or heavily polluting, category. They are also required to follow the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Slaughter House) Rules, 2001, besides requiring a licence to operate from the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) to ensure adherence to health standards for meat.

In reality, however, most of India’s animal slaughtering is performed in small-scale butcher shops or houses. In the cities, butchers take larger animals including cattle to slaughterhouses, mostly those run by the government, where they pay a service fee.

Before the NGT order, the Supreme Court had in 2012 asked states to modernise slaughterhouses and establish monitoring committees to oversee their operation.

The UP state government in 2014 launched a scheme to build modern abattoirs with waste management and water use regulations. It allocated money for upgrading and setting up 10 modern slaughterhouses in cities including Kanpur, Lucknow and Varanasi. The Colonelganj facility, from where Shafiq operated, was listed for redevelopment too.

The State Urban Local Bodies Department allocated Rs 12.43 crore for the project, sanctioning a first instalment of Rs 4.97 crore in December 2016. Before any of the slaughterhouse projects could materialise, however, the Bharatiya Janata Party won the state assembly elections in March 2017, and began a crackdown on animal slaughter.

“Earlier, around 100 buffaloes were slaughtered in Kanpur every day,” said Irfan Ahmed, a meat supplier in the city. About 80 of these would be butchered in the government slaughterhouses where meat sellers lacking adequately large premises could bring an animal, pay a fee of Rs 25, and take away the meat and other animal parts.

Small vendors who could not afford a whole buffalo could buy small portions of meat for resale from these facilities. “With their closure, there is no public space available and many have lost their livelihood,” Ahmed said.

According to the Uttar Pradesh Municipal Corporation Act, 1959, however, the construction and maintenance of slaughterhouses is an obligatory duty of the municipality. The Allahabad High Court also cited this provision in 2017, while hearing a bunch of petitions against the ban on slaughter.

The court ordered the state government to provide licences and set up requisite facilities for slaughtering and meat selling. Checks on unlawful activity should be simultaneous with facilitating the conduct of lawful activity relating to food, food habits and vending, the order said, adding that these activities are “undisputedly connected” with the right to life and livelihood.

“Food that is conducive to health cannot be treated as a wrong choice,” the order said.

In 2018, however, the state legislative assembly where the BJP enjoys an absolute majority amended the law, limiting the government’s responsibility only to the regulation of slaughterhouses.

A set of petitions against the closures, filed by butchers and meat sellers, is still pending in the Allahabad high court. In response to RTI applications filed by Article 14, the municipal corporations in Kanpur and Lucknow accepted that there are no plans for modern slaughterhouses in the two cities.

The inaction by the state government on upgrading public slaughterhouses is evidence that the motive was not to prevent pollution, but to curtail the meat trade, said Shahabuddin Qureshi, general secretary of Qureshi Foundation, an association of butchers and meat-sellers in Lucknow.

“The meat industry won’t stop operating just because a law has been passed,” said Qureshi. “It has scaled down but continues illegally, causing a big revenue loss to the government.”

A similar situation prevailed in other cities and towns.

Agra and Bareilly were outliers, their municipal corporations now running modern abattoirs. Both towns’ experience was that setting up modern slaughterhouses was beneficial not only for those seeking to purchase hygienic meat but also to generate revenue. In 2019-20, Agra Municipal Corporation earned Rs 6.22 crore in fees from slaughterhouses, while Bareilly Municipal Corporation earned Rs 2.83 crore.

According to Shahabuddin Qureshi, such slaughterhouses in all 75 districts of the state could bring in revenue to the tune of Rs 150 crore, while ensuring safe and affordable meat for the people.

Lucknow-based animal rights activist and former member of the Animal Welfare Board of India Kamna Pandey agreed that animal slaughter in the state is currently too scattered to regulate. Government abattoirs, on the other hand, could have centralised processes and enforced rules such as stunning of animals before slaughter.

“In the current scenario, the government is neither able to curb slaughtering nor ensure pollution, hygiene and safety standards,” Pandey told Article 14.

Underground Trade Runs on Bribes, Slimmer Profits

The Allahabad high court had instructed the state government to issue new licences and renew old ones for animal slaughter and meat trade. Barring Kanpur, not a single city or district administration began this process of issuing renewals.

The Kanpur Municipal Corporation allowed retailers to operate in the city on the condition that they procure meat from the modern slaughterhouses run by private companies.

These were previously export-only operations for buffalo meat. With local retailers having to purchase from these units, meat prices rose. Kanpur’s retail prices of buffalo meat are the highest in the state, though shopkeepers’ profit margins simultaneously waned.

“Most retailers buying meat from export houses are under debt because their profit margin has reduced,” said Mukeem Qureshi, a retailer in Kanpur.

When they procured meat from local slaughterhouses, along with the buffalo meat they also got horns, hide, fat (tallow) and other material, all tradeable items that brought small profits. The large units, however, retained these items.

“Some influential butchers who are still secretly slaughtering animals on their premises are in a better position,” said Mukeem Qureshi. “But they have to pay a bribe of anywhere between Rs 80,000 to Rs 100,000 per month to the police and municipal officials.”

Commissioner of Police (Kanpur) Vijay Singh Meena said he had not looked into this issue. “I have joined recently and am not aware of such illegal slaughtering or meat selling but if there are any complaints, we will definitely investigate that,” he told Article 14.

Lucknow recorded a sizable shrinking in the trade of meat since 2018, for none of the butchers or meat sellers in the city was issued a no-objection certificate or licence to operate.

Aslam Qureshi, who used to supply mutton to around 15 franchise stores of a supermarket chain, said he lost this client to a large frozen meat company because he didn’t have a licence. “We were dependent on government infrastructure,” he said. “How can they withdraw that without offering any alternative?”

Their business driven underground, meat shops in Lucknow have continued to operate but at lower profit margins and in a cloud of uncertainty and fear of an official crackdown.

Initially, the municipality was strict but over the years, traders have learnt to “manage through bribes”, according to one shop owner selling buffalo meat in the city who spoke to Article 14 on the condition that he would remain anonymous. “We also get information about any raids and we roll down our shutters before that,” he said.

Animal welfare activists confirmed this. Pandey, the former animal welfare board member, said officials often do not act on their complaints about unauthorised animal slaughter in the city. “What works is taking help from organisations like Hindu Yuva Vahini because they have access to top officials and ministers,” she said.

Arvind Rao, chief veterinary officer of the Lucknow Municipal Corporation, denied receiving any complaints against government officers accepting bribes to allow animal slaughter or meat trade. “These are unauthorised businesses, but we do act against them regularly?” he said.

The municipality did not issue no-objection certificates or licences, and no unit applied, he said, because these units did not meet the conditions for slaughtering of animals or sale of meat.

For smaller towns and villages, the forced closure of slaughterhouses and meat shops sounded the death knell for these businesses.

Mohammad Faisal who earned Rs 1,000-Rs 1,500 daily from his meat shop in the town of Behta, 20 km from Lucknow, reluctantly shuttered his little store after the district administration refused to renew his shop’s licence, earlier renewed annually. He also had a court order that allowed him to slaughter buffaloes.

Since 2017, Faisal has been unable to get a licence. “There has been no response to my online application for renewal,” he said. “When I met the officials, they said there is no government order on the issue yet.”

He joined his relatives selling live buffaloes to an export house, but said earnings fluctuate and he sometimes incurs losses on account of his unfamiliarity with the work. Compared to buying, butchering a buffalo and selling its meat and various other products, this work fetched considerably lower incomes.

In Haidargarh town of Barabanki district in central UP, at least seven families engaged in trade of buffalo meat closed down their businesses entirely. The rules are more strictly enforced in smaller towns, said Ayub Qureshi, a butcher in Haidargarh. “Everyone is scared that even if we slaughter a buffalo, a case of cow slaughter will be slapped on us,” he said.

In fact, the Allahabad high court’s 2017 order took note of the unique position of smaller towns or villages and their biweekly or daily local markets that cater to local needs. “The State has therefore to assess this aspect of local issues including remote and far flung areas where availability of even basic facilities is still a mirage…” the order said.

If facilities meeting the conditions are absent in rural areas, then the state government must consider permitting continuance of petty vendors’ trade, it said.

Ancillary Industries Take a Hit

The district town of Sambhal near Moradabad in western UP is known for handicrafts, including buttons, cutlery, ornaments and furniture embellishments, made from animal bones and horns. Both items now more expensive than earlier, local suppliers of the raw material were forced out of the trade by market forces.

Artisans have had to buy animal bones and horns from meat-exporting units, the only ones slaughtering at a big scale, said Tareef Ilahi, owner of Sky Horn Bone Crafts in Sambhal. “If bone was available at Rs 20 per kg five years back, it now costs Rs 50. Similarly, the price of horn today is Rs 100 per kg, up from Rs 50 earlier,” Ilahi said.

Export houses have also been unable to meet the demand. “What was available to us from within the state at a low price has to now be fetched from Maharashtra or West Bengal,” said Mubeen Ashraf, president of the Sambhal Handicrafts Development Association. “The transportation also comes at risk of attacks from Hindu groups who claim that the animal parts belong to cows and hence should not be used.”

The raw material shortage dented the viability of the handicraft trade, impacting production cycles and reducing profit margins. “Earlier an item that cost us Rs 500 was sold at Rs 1,000, but now the same thing costs us Rs 700 but cannot be sold at more than Rs 1,100,” said Ashraf, “because there is competition from other manufacturers in Sambhal and from other states like Rajasthan.” From five to six production cycles a year, these units now only have three production cycles annually, they said.

The household handicraft units in Sambhal were hit the hardest as the bigger manufacturers cornered the suddenly smaller supply.

“For us, the rates have increased by almost three times the earlier price,” said Mohammad Salin who has a small machine installed at home to mould horns and bones. Six members of his family used to work together to earn Rs 15,000- Rs 20,000 a month. “Now it’s tough to earn even Rs 10,000,” he rued.

Animal Rearing a Risky, Unprofitable Business

The impact on animal rearing in the state has been multifold and complex.

Many animal rearers said they had either reduced the size of their flocks or left the traditional livelihood altogether, even if migration to a city was the only alternative.

The buyer base having shrunk, many small animal markets shut down. Meanwhile, the cost of fodder rose exponentially.

“Earlier, animal keeping was a dependable business,” said Mohanlal of Mathna village in Sitapur district, who uses one name. Many landless families reared goats while small farmers had cows and buffaloes that they could sell to fund weddings or during health emergencies. Now only big farmers or those living close to cities where milk can fetch a good price can rear animals, he said. “The price of fodder has gone upto Rs 1,000 per quintal, but selling animals doesn’t fetch a good return.”

Three animal markets near Mathna have closed since 2017. Buffaloes and goats are now purchased by travelling traders. While animal rearers could compare rates and choose the highest bidder in the markets, in recent years they have had to sell at whatever price is offered. “A buffalo that would sell for Rs 20,000 now fetches around Rs 12,000,” said Mohanlal.

Rising farm mechanisation was one reason for lower fodder availability over the years, on account of the foliage not being saved for animals. As the population of stray cattle rose after 2018, farmers also began to prefer non-cereal crops, to prevent the destruction of crops by animals.

“Earlier, we were able to sell bulls or male calves but now that’s not possible. Both the police and cow vigilantes are on the lookout, which is why no one wants to take the risk of trading cows, even if not for slaughter,” said Sudama Singh of Singhora village in Gorakhpur district in eastern UP.

This meant that bulls or male calves earlier sold easily were now allowed to roam free instead. “There is such a large number of roving cows and bulls in the villages that it’s difficult to save the crops,” said Singh.

Many farmers shifted from wheat, rice, groundnut, flaxseed, sesame and mustard to sugarcane, a crop more resilient against grazing by stray animals. This shift in crop pattern, however, meant less animal fodder from the fields, said Surbala of Satnapur village in Sitapur district.

“We never used to buy fodder… Last year, I purchased fodder worth Rs 27,000 for the one buffalo I keep now,” she said. “Who will rear animals if maintenance cost is so high and not much is earned on their sale?”

(Manu Moudgil is an independent journalist based in Chandigarh. Article courtesy: Article14.com.)