It doesn’t even shock anymore. At a time when consumers shell out Rs 40 per kg for bhindi, the wholesale price for this vegetable has dropped to Re 1 per kg at Badwani in Madhya Pradesh. Media reports showed how an irate farmer had used a tractor-driven cultivator to flatten the standing crop in four acres. Faced with a sudden drop in prices, some other farmers in the same district were forced to allow cattle to feed on the standing crop. Not peculiar to just Madhya Pradesh, distress sale of vegetables has been a recurring tragedy across the country.

Now let’s look at the plight of sugarcane growers in Punjab. As the new crushing season begins, 14 of the 16 sugar mills (in the cooperative and private sectors) have yet to pay outstanding cane arrears of Rs 250-crore from last year’s cane crushing season. Punjab is not an exception, the unpaid cane dues across the country amount to Rs 15,683-crore as on September 11, with Uttar Pradesh topping the chart, Parliament was recently informed in a written reply. A recurring problem, sugarcane farmers have somehow managed to survive for a year (and at times for two years in a row) without being paid their dues in time. Imagine, if the salary of employees is delayed by even a month or so!

What is so unusual about these reports, you may ask. After all, this is a routine affair. Every now and then, reports of angry farmers throwing tomatoes, potatoes and onions on the streets appear in the media when the prices slump. This is despite the launch of the Operation Greens scheme with an outlay of Rs 500 crore, in the Budget speech of 2018-19. It aimed at stabilising the prices of tomato, onion and potato (TOP) comprising a larger share of an average household’s vegetable basket. The scheme, which has for all practical purposes, remained a non-starter, has now been extended to cover all fruits and vegetables (called TOTAL) for a period of six months beginning June.

Notwithstanding these announcements, the prices of seasonal vegetables have by and large remained depressed. Even before the lockdown disrupted the local value chain, vegetable growers have been repeatedly hit by price volatility. In the absence of any benchmark price — like the Minimum Support Price (MSP) for cereals and other major crops — most vegetable farmers do not even realise whether the price they are being offered in the markets is truly remunerative or not. There have been instances when farmers have actually returned almost empty-handed from markets after deducting expenses incurred for harvesting/plucking and adding transportation charges.

In fact, when farmers undertake cultivation, they do not realise that they are actually cultivating losses. An OECD-ICRIER study for 2000-16 showed that Indian farmers lost roughly Rs 2.64-lakh crore every year on being denied the rightful price. This surely is an underestimate, considering that only a limited number of crops was studied, but it clearly shows how severely farmers are at the receiving end year after year.

Diversifying the cropping pattern without first ensuring that farmers receive an assured price for their produce is, therefore, meaningless. This is primarily the reason why Punjab farmers have spurned every effort to diversify from the intensive wheat-paddy crop rotation. There is no denying that diversifying to pulses, oilseeds, millets and pulses is desirable, but in the absence of an assured price and effective procurement system in place, farmers cannot be expected to shift to a cropping pattern that leaves them to face the vagaries of market forces. For decades, farmers have silently borne the brunt of an economic design that has left them struggling and fighting for fair wages while mainline economists over the years failed to see beyond the industry prescriptions.

Even in America, where market reforms in agriculture have been in place for several decades, small farmers have been left in the lurch. Although US agriculture is perceived to be quintessential, which, being part of national and international value chains, is believed to have brought prosperity on the farm, the reality is to the contrary. According to the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), the farmers’ share in every dollar consumers spend on food (in 2018) comes to a paltry eight per cent. In addition, there are numerous studies that tell us that ever since big retail came into existence, farmers’ share in food dollar has actually come down.

Compare this with the Amul dairy cooperative structure where farmers get 70 to 80 per cent of every rupee consumers spend on milk. Isn’t, therefore, the homegrown dairy cooperative model a better design to be extended for agricultural commodities as well? If the entry of big business in American agriculture hasn’t benefited small farmers, and in reality has pushed them out of farming, shouldn’t India be learning from its own successful brand of cooperative dairies? Why can’t policy-makers think of creating a new economic design which provides at least 40 to 50 per cent (if not 70-80 per cent like in milk) of the consumer price to farmers?

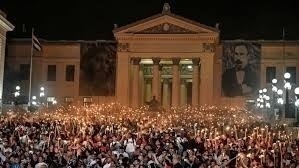

The farmers’ march to New Delhi actually is a pointer to the injustice that economic reforms have continuously inflicted on agriculture by keeping farm prices low. Braving water cannons in the cold weather, farmers seek an end to the long winter. After all, how long can agriculture be kept deliberately impoverished to keep the economic reforms viable? Farmers, too, have families to take care; their children, too, have aspirations; for which they, too, need an assured monthly income package. Seeking a Minimum Support Price (MSP) below which trading does not take place, farmers are essentially asking for evolving a mechanism whereby they do not have to throw vegetables on the streets, where they do not have to resort to distress trade.

The continuing drought in framing farmer-friendly policies has to end. The farmers’ march should be seen as a wake-up call to make appropriate policy corrections to set the historic imbalances right, and thereby bring back the pride in farming.

(Devinder Sharma is an agricultural economist.)