Scores of sugarcane planters hack at the bare ochre hillside in Alagoas in northeastern Brazil with four-foot hoes, tilling up to four miles of land per day for just 41 Brazilian reals. That’s less than $8, for each backbreaking shift.

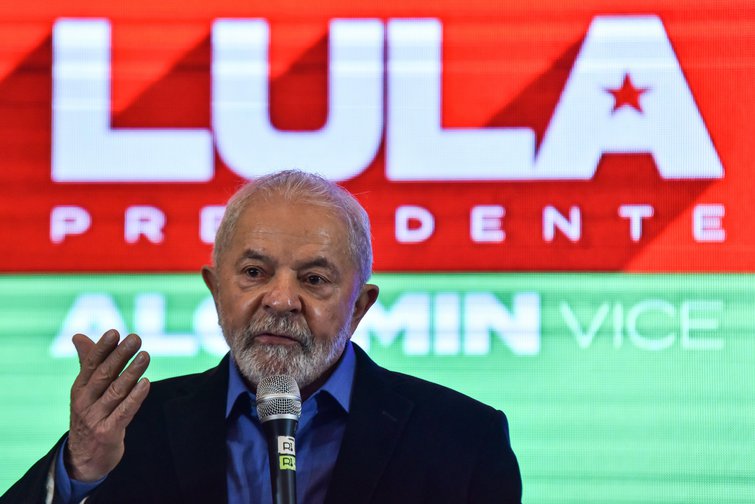

The workers’ daily wage does not go very far these days in Brazil. Food and fuel costs are soaring, driven by multinational and commodity speculators. The spectre of hunger is back in rural Alagoas, ranked seventh in the 2021 poverty index of 146 Brazilian municipalities compiled by Marcelo Neri of the Getulio Vargas Foundation (FGV). In Alagoas, 64% of the population earns less than $5.50 a day and many of the workers, as in other parts of the country, are counting the days until the 2 October presidential election and an expected victory for former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva at least in the 30 October run-off.

“Lula will bring down the prices,” said Jose, a cane planter in his thirties, recalling the massive social transformation for low-paid workers – especially in the northeastern region – engineered by Lula’s Workers Party governments between 2002 and 2014. His father and grandfather both worked cutting sugarcane and his more distant relatives served as plantation slaves.

Jose and other workers wait in the searing heat by the company bus, which will take them back to the sugar mill, the Usina Santo Antonio, and the company accommodation. The company has refused to provide more than one trip per day back to the residential quarters, forcing the workers to wait in the heat until the end of the second shift.

“We’re at work while waiting but with no pay,” recalled another worker, who has been working and living on the company property for 25 years. “When Lula was president, we found out for the first time that we have the right to overtime pay.”

High food prices are especially bad for sugarcane planters and cutters because “the owner won’t let us plant our own crops (beans, yuca, and other staples) on company property to feed ourselves”, said Ribamar, a worker in his twenties.

Ironically, in Brazil, the world’s largest sugar producer and where cane-based ethanol is widely used at the gas pump and mixed with gasoline, the soaring price of sugar contributes to both fuel and food inflation.

Although Brazilian sugarcane is now mainly grown in the southern state of Sao Paulo, it is symbolically linked to states in the north-east, where the 18th-century plantation economy eroded topsoil and forests. As the late Eduardo Galeano, the Uruguayan writer whose work illuminated the history and politics of the entire continent, noted in ‘Open Veins of Latin America’, the region, which was “naturally fitted to producing food”, was turned into “a place of hunger”.

In the 2000s, Lula’s 2003 cash-transfer programme, Bolsa Família, as well as greater rights for workers and improved wage bargaining and conditions all contributed to a reduction in inequality. The Workers’ Party, known by its Portuguese initials PT for Partido dos Trabalhadores, also invested in public infrastructure, especially water. But right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro has set the clock back.

“Bolsonaro has hollowed out the institutions which monitor labour rights and conditions,” said Alexandre Valadres, an expert on rural labour at the Institute of Applied Economic Research in Brasilia. He pointed out that “sugarcane, like any other monoculture, squeezes out family agriculture” – making sugarcane workers’ situation especially precarious.

Rural labour unions, often the only support for workers threatened by armed gangs in remote areas, are starved of financing.

“Most of our offices will close down if Bolsonaro stays in power,” said Ze Areia of the rural workers federation (Fetagri) in Ourilandia, a village in Pará state, in the Amazon region. Violence against labour and community leaders has soared in Pará since Bolsonaro came to power in 2019. Areia says that Paulino da Silva, his colleague in Fetagri’s small Ourilandia office was murdered last year.

Lula, who was born into poverty in the village of Caetés, 150 miles north of the San Antonio sugar mill, is now seen as the only hope for a huge swathe of low-income workers in Brazil in the poor northeast region, in the Amazon and in the urban favelas of Rio or São Paulo.

According to Datafolha opinion polls, more than 50% of workers earning 2,200 reals (around $400) or less per month will vote for Lula. But the dilemma for these sugarcane workers – that they are mostly unable to grow their own food even as they work in a monoculture commodity economy – reflects a larger dilemma for the PT’s economic planners.

‘Hunger in a sea of grain’

More than at any time since the early 20th century, the Brazilian economy is driven by commodity exports, from basic foods such as cereals or beef to minerals such as iron, as well as offshore oil drilling in the Atlantic.

Soy, corn, cotton and sugar exports are driving the profits of agribusinesses, especially in states such as Mato Grosso, a Bolsonaro stronghold in west-central Brazil, where new ‘soy cities’ are being built on the edge of the Amazon rainforest.

Soaring international commodity prices, exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, have translated into huge profits for big soy farmers, commodity traders such as Cargill and Bunge, and global equity funds.

But small producers are being squeezed, investment in manufacturing industries is flat, and most of the population is badly hit by surging food prices. “We are seeing hunger in a sea of grain,” said Luiz Alberto Melchert, a Brazilian economist specialising in agribusiness.

The upshot is that if Lula wins this election, he will face a stark choice. Redistribute income from the commodity boom via social programmes, just as he did two decades ago – but now with greater budgetary constraints and less predictable commodity prices – or, transition to a development model that is less dependent on big agribusiness and other extractive industries. So far it’s unclear what PT will choose to do.

High public debt and rising interest rates will make progressive tax hikes a necessary part of any redistribution strategy. Economists close to Lula, such as Guilherme Mello at São Paulo’s State University of Campinas, advocate a greater focus on industrial policy and public investment in manufacturing and a reduced emphasis on commodity exports.

Pressure from the environmental movement to counter the deforestation of the Amazon, which has proceeded at record rates under Bolsonaro, may also force a change in Brazil’s commodity growth model. But with cash crops in greater demand internationally, triple-digit oil prices forecast to stay, and a global energy transition boosting demand for iron and other commodities, the chances of fully breaking from this commodity exports-based model are low.

A new pink tide?

The dilemma is a familiar one in other South American countries where left-wing governments have recently taken charge, such as Chile, Colombia, Bolivia and to some extent Peru.

From Caracas to La Paz, Santiago de Chile to Brasilia, governments that swept into office on the first pink tide in the early 2000s based their wealth redistribution and anti-poverty programmes on a huge windfall from the so-called commodity price supercycle. This saw high raw material prices for nearly two decades but the growth model fell apart in 2013, when oil and other commodity prices went into free fall. Now, with supply chains in flux and greater concerns for the environment – driven largely by citizens’ movements on the streets of Bogota and Santiago – governments are having to rethink.

Consider Colombia’s new president Gustavo Petro, an economist and former guerrilla fighter. Defining his agenda as the defence of “life” against the fossil fuel, mining and big business oligarchy, the newly-elected Left leader has promised to phase out oil exploration, reduce the number of mining licences and create alternatives to export-led agribusiness.

Petro has appointed Irene Velez, an economist who specialises in political ecology and environmentalism as minister of energy and mining. His vice-president, Francia Márquez, a Black activist who won the Goldman Environmental Prize for stopping illegal gold mining on ancestral Afro-Columbian land, is another powerful anti-extractivist voice in the government.

“Colombia is moving towards a less extractive economy,” said Joan Martinez Allier, an influential environmental economist at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona in Spain.

But the challenges of transitioning to renewable energy and an agricultural model based on food sovereignty remain. So does the potential for a Chilean-style backlash. Chileans recently rejected a progressive new constitution. If Colombia moves too fast down a new path to the future, it too can backfire. Already, the Right, led by former Colombian president Alvaro Uribe, is attacking plans to downscale fossil fuels, mining and fracking. The decision to allow subsidised gasoline prices to rise – a trigger in the past for protests in countries such as Ecuador – will also test the popularity of Petro’s government.

Chile as a warning

In fact, Chile foreshadows the dangers of prioritising environmental rights and anti-extractive policies. When 60% of Chilean voters recently rejected a draft constitution that recognized nature’s “right to respect and protect its existence” , it was because many saw it as detached from the reality of a commodity-based economy.

That defeat will surely weaken the government of former student leader Gabriel Boric, who won the election in December 2021 as the youngest president in Chile’s history on a radical agenda for change.

Boric plans to turn Chile’s economy, which is dependent on copper exports, into a strategic supply hub for the electric vehicles and photovoltaic cells needed in the global energy transition. The country’s huge lithium mines in the Atacama Desert will be important in the lithium-ion battery revolution that will power electric vehicles, home energy storage and even entire cities. Boric also hopes to boost investment in wind farms in Chilean Patagonia, close to the Arctic, where multinational projects to manufacture and export green hydrogen and renewable fuel are underway.

But in a country stricken by drought, it is not easy to pursue lithium and copper mining as well as water-guzzling hydrogen production projects in order to save the planet.

Meanwhile, Bolivia’s socialist president Luis Arce provides a compelling case for a more extractive approach to social development. The country is using the old socialist model of state-owned mining and fossil fuel extraction to finance social programmes. So far, the model has maintained former president Evo Morales’ spectacular achievement, before he was removed in a 2019 US-backed coup, of reducing extreme poverty from 45% to 11%.

So the dilemma remains for Latin America’s Left. Should it pursue the familiar agenda of growth driven by resource extraction or a new model based on smaller-scale agriculture and climate change-led industrial transformation? Until it can decide, Latin America’s ‘open veins’, as Eduardo Galeano called them, will continue to bleed.

(Andy Robinson is the Latin American correspondent for Barcelona daily La Vanguardia. His latest book, ‘Gold, Oil and Avocados’, is now available at Melville Press. Courtesy: openDemocracy, an independent global media organisation based in the United Kingdom that seeks to educate citizens to challenge power and encourage democratic debate across the world.)