‘[I] have the greatest admiration for Gandhi and for the Indian tradition in general.’

– Albert Einstein, 1950

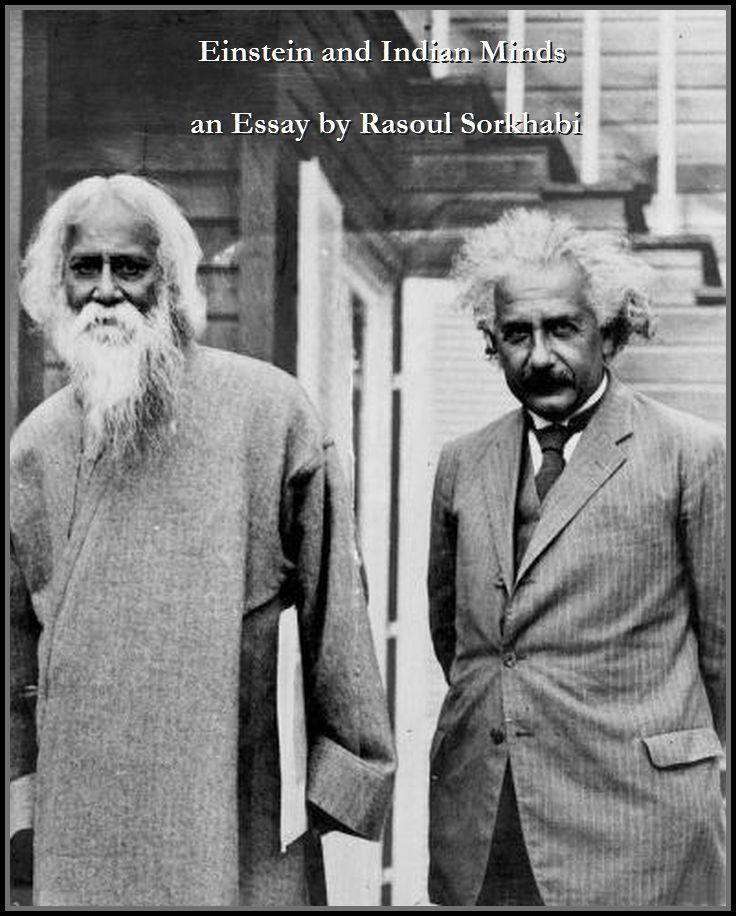

In reading Albert Einstein’s biographies[1-6], I noticed that he had connections with three great Indian minds of the early twentieth century: Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941), Mahatma Gandhi (l869–1948) and Jawaharlal Nehru (1889–1964). Of course, Einstein as well as these three Indian leaders were famous in their lifetimes, so these connections should not come as a surprise. But my interest in this topic grew as I wondered what drew these great minds together. Einstein was not the type of person to be attracted to the exotic East for shallow sentimental reasons. This article chronicles Einstein’s connections with these three men, and shows how Einstein saw some of his ideas and ideals in the Indian mind embodied, to varying degrees, in Tagore, Gandhi and Nehru. Of all Einstein’s biographers, Abraham Pais[4,5] has paid more attention to his Indian connections. While, in writing this historical essay, I have benefited from Pais’ research, I have also added information and ideas using other sources.

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of Einstein’s death. This article is offered as homage to these four intellectual giants, and as a way of remembering some aspects of their lives and thoughts. However, the importance of this topic goes beyond this annual occasion because the first half of the twentieth century, during which these gentlemen lived, was devastated by two world wars, and as we are in the early years of a new century and as the world is still immersed in prejudice and violence, these great minds are quite relevant to our times and to our generation.

Einstein and ‘Rabbi’ Tagore

Einstein (born in 1879) was eighteen years younger than Tagore. Tagore won the Nobel Prize in literature in 1913; Einstein won the Nobel Prize in physics in 1922.

Einstein used to refer to Rabindranath Tagore as Rabbi Tagore.[7] The first time they met each other was in Germany shortly before World War I. In l912, Tagore visited Europe. His reminiscences of meeting with Einstein were published much later. Tagore remarked:[8]

Einstein has often been called a lonely man. Insofar as the realm of the mathematical vision helps to liberate the mind from the crowded trivialities of daily, I suppose he is a lonely man. He is what might be called a transcendental materialism, which reaches the frontier of metaphysics, where there can be utter detachment from the entangling world of self. To me both science and art are expressions of our spiritual nature, above our biological necessities and possessed of an ultimate value …

Einstein is an excellent interrogator. We talked long and earnestly about my ‘religion of man’. He punctuated my thoughts with terse remarks of his own, and by his questions I could measure the trend of his own thinking.

During their discussion, an important difference of opinion between Tagore and Einstein revolved over whether there was truth in the world independent from human mind. Tagore argues that ‘the truth of the Universe is human truth … when our universe is in harmony with man, the eternal, we know it as truth, we feel it as beauty.’ Einstein replies: ‘I agree with regard to this conception of Beauty, but not with regard to Truth.’ Tagore insists that ‘truth is realized through man’. Einstein illustrates his point of view: ‘For instance, if nobody is in this house, yet that table remains where it is.’ To which Tagore replies: ‘Yes, it remains outside of the individual mind but not the universal mind. The table which I perceive is perceptible only by the same kind of consciousness which I possess.’ In his article, Tagore summarizes their discussion: ‘I could see that Einstein held fast to the extra-human aspect of truth. But it is evident to me that, in human reason, facts assume a unity of truth which is only possible to a human mind.’[8]

Einstein continued to believe in extrahuman existence of truth and even coined the term ‘objective reality’[9] to highlight his belief. The relation of truth to human mind seems to have occupied Einstein for decades. Pais[10] remembers that in 1950 while accompanying Einstein on a walk from Princeton University to his home, Einstein ‘suddenly stopped, turned to me, and asked me if I really believed that the moon exists only if I look at it.’ The discussion between Einstein and Tagore is closely related to the ‘anthropic principle’ later developed in physics and cosmology (see ref. 11 for detailed information) even though it has escaped the attention of many authors.

In 1929, Tagore sent a postcard (dated 22 December) to Einstein from India: ‘My salutation is to him who knows me imperfect and loves me. My best wishes.’[12] It is not clear what the occasion was for sending this postcard; it may have been for new year’s greetings.

The second Einstein–Tagore meeting took place on 14 July 1930 at Einstein’s summer house in Caputh near Berlin. This dialogue was written down by a friend who was present, and has been published both in India[13] and in the USA[14]. Most of their talks were about music. Einstein was not apparently happy with the second dialogue and wished that it had not been published.

On 30 September 1930, Romain Rolland wrote to Einstein asking him for a contribution to a book to be presented to Tagore on the occasion of his 70th birthday the following May. Einstein replied on 10 October 1930:

I shall be glad to sign your beautiful text and to add a brief contribution. My conversation with Tagore was rather unsuccessful because of difficulties in communication and should, of course, never have been published. In my contribution, I should like to give expression to my conviction that men who enjoy the reputation of great intellectual achievement have an obligation to lend moral support to the principle of unconditional refusal of war service.[15]

Interestingly, two days after this letter, a manifesto was released by Einstein, Tagore and Rolland, appealing against conscription and the military training of youth.[16] The Golden Book of Tagore came out in 1931, and its preface was signed by Einstein, Gandhi and Rolland. Einstein’s contribution to the book reads:

You are aware of the struggle of creatures that spring forth out of need and dark desires. You seek salvation in quiet contemplation and in the workings of beauty. Nursing these you have served mankind by a long, fruitful life, spreading a mild spirit, as has been proclaimed by the wise men of your people.[17]

In May 1931, Tagore sent a postcard, written in Bengali and English, to Einstein thanking him for his tribute: ‘The same sun is newly born in new lands, in a ring of endless dawns.’[18] The third (and probably the last) Einstein–Tagore meeting took place on 14 December 1930 during Einstein’s one week visit to New York. No record of this meeting was ever published. We have the following telegram sent by Einstein aboard ship to Tagore: ‘I congratulate you from my heart with your meeting. May it be given to Tagore also on this occasion to work successfully in the service of his ideal to bringing nations together.’[19]

In 1932, when Tagore was visiting Tehran, an Iranian mathematician asked his opinion about Einstein. This is what Tagore said:

In addition to his reputation in mathematics and science, he is a good and kind man who has withdrawn himself from the world and its superficialities. He is devoted to humanity and peace. He is a sincere supporter of peace and has pledged his life to this cause. In his speeches in America he has expounded the harm of war and the benefits of peace. He is indeed a great man. He is in no way fanatic about race, and looks upon all peoples as equal. Einstein is the greatest thinker of this age.[20]

Einstein and Mahatma Gandhi

Einstein and Gandhi never met each other although they desired to do so. Einstein’s first recorded admiration for Gandhi is as early as July 1929 in an interview with the Christian Century.[21]

The only Einstein–Gandhi correspondence, which we know of, took place in 1931. This letter was sent to Gandhi through Sundaram, an acquaintance of Gandhi, who had visited Berlin, where Einstein was then living. At that time, Gandhi was visiting London to attend the Round Table Conference on Indian Constitutional Reform. On 27 September 1931, Einstein wrote to him:

You have shown by all you have done that we can achieve the ideal even without resorting to violence. We can conquer those votaries of violence by the non-violence method. Your example will inspire humanity to put an end to a conflict based on violence with international help and cooperation, guaranteeing peace of the world. With this expression of my devotion and admiration, I hope to be able to meet you face to face.[22,23]

On 10 October 1931, Gandhi replied from London:

I was delighted to have your beautiful letter sent through Sundaram. It is a great consolation for me that the work I am doing finds favor in your sight. I do indeed wish that we could meet face to face and that too in India at my Ashram.[24,25]

Einstein’s admiration of Gandhi was not, however, extended to Gandhi’s ideas on economics. In an interview with the Graphic Survey in 1935, Einstein was quoted to have said:

I admire Gandhi greatly but I believe there are two weaknesses in his program; while nonresistance is the most intelligent way to cope with adversity, it can be practiced only under ideal conditions. It may be feasible to practice it in India against the British but it could not be used against the Nazis in Germany today. Then, Gandhi is mistaken in trying to eliminate or minimize machine production in modern civilization. It is here to stay and must be accepted.[26]

As Einstein’s mild criticism of Gandhi’s ideas on economics and the limitation of his non-violence movement were based on Einstein’s own analysis and an honest commentary on Gandhi, his admiration of Gandhi and the ideas of non-violent ways of solving political problems were equally honest and significant. In 1939, Einstein received a letter (dated 12 January) from S. Radhakrishnan, then a professor of Eastern religions at Oxford and one of Gandhi’s followers, requesting him to contribute to a volume of articles planned to be published on Gandhi’s 70th birthday. Einstein gladly accepted and contributed the following to the Birthday Volume Gandhi (1939):

Mahatma Gandhi’s life’s work is unique in political history. He has devised a quite new and humane method for fostering the struggle for liberation of his suppressed people and has implemented it with greatest energy and devotion. The normal influence which it has exerted on the consciously thinking people of the entire civilized world might be far more lasting than may appear in our time of overestimation of brutal methods of force. For only the work of such statesmen is lasting who by example and educational action awaken and establish the moral forces of their people.

We may all be happy and grateful that fate has given us such a shining contemporary, an example for coming generations.[27]

For the same occasion, Einstein also made a statement about Gandhi, which was first published in his anthology, Out of My Later Years (1950):

A leader of his people, unsupported by any outward authority: a politician whose success rests not upon craft nor the mastery of technical devices, but simply on the convincing power of his personality; a victorious fighter who has always scorned the use of force; a man of wisdom and humility, armed with resolve and inflexible consistency, who has devoted all his strength to the uplifting of his people and the betterment of their lot; a man who has confronted the brutality of Europe with the dignity of the simple human beings, and thus at all times risen superior.

Generations to come, it may be, will scarce believe that such a one as this ever in flesh and blood walked upon this earth.[28]

Gandhi was assassinated on 30 January 1948. Three weeks later, a memorial service was held for Gandhi in Washington, D.C., and Einstein wrote the following eulogy:

Everyone concerned with a better future for humankind must be deeply moved by the tragic death of Gandhi. He died a victim of his own principle, the principle of nonviolence. He died because, in a time of disorder and general unrest in his country, he refused any personal armed protection. It was his unshakable belief that the use of force is an evil in itself, to be shunned by those who strive for absolute justice.

To this faith he devoted his whole life, and with this faith in his heart and mind he led a great nation to its liberation. He demonstrated that the allegiance of men can be won, not merely by the cunning game of political fraud and trickery, but through the living example of a morally exalted way of life.

The veneration in which Gandhi has been held throughout the world rests on the recognition, for the most part unconscious, that in our age of moral decay he was the only statesman who represented that higher concept of human relations in the political sphere to which we must aspire with all our powers. We must learn the difficult lesson that the future of mankind will only be tolerable when our course, in world affairs as in all other matters, is based upon justice and law rather than the threat of naked power, as has been true so far.[29]

Toward the end of the same year, on 2 November 1948, Einstein sent a message to the Indian Peace Conference, with these closing words: ‘Let us do whatever is within our power so that all the peoples of the world may accept Gandhi’s gospel as their basic policy before it is too late.’[30]

After Gandhi’s assassination, an artist from Calcutta and a physics professor from Ambala sent letters to Einstein criticizing the late Gandhi for his negative attitude toward science and industrialization, and showing their dismay as how Einstein could respect such an irrational person. In reply to the Calcutta-based artist, Einstein wrote: ‘There may be some truth in your criticism of Gandhi’s attitude towards technology. I think, however, that his merits with respect to the liberation of India and the principle of nonviolence are so unique that it seems not justified to search for such a small weakness in such as great personality.’ And writing to the physics professor, Einstein responded: ‘… Gandhi’s autobiography is one of the greatest testimonies of true human greatness … Do you believe it justified to murder anyone who has some opinion different from yours?’ The Ambala professor sent two more letters calling Gandhi a Hitler and justifying his assassination; Einstein obviously did not consider these letters worthy of replying.[31]

Einstein’s admiration of Gandhi lasted to the end of his life. He had a portrait of Gandhi in his house, which still exists. Einstein praised Gandhi on numerous occasions.[5,15,23] On 18 July 1950, during a broadcast by the United Nations under the title, ‘The pursuit of peace,’ Einstein said:

I believe that Gandhi held the most enlightened views of all the political men in our time. We should strive to do things in his spirit; not to use violence in fighting for our cause and to refrain from taking part in anything we believe is evil.[32]

And in 1952, in a letter to the Asian Congress for World Federation, held in Hiroshima on 3–6 November, Einstein wrote:

Gandhi, the greatest political genius of our time, indicated the path to be taken. He gave proof of what sacrifice man is capable of once he has discovered the right path. His work in India’s liberation is living testimony to the fact that man’s will, sustained by an indomitable conviction, is more powerful than material forces that seem insurmountable.[33]

Writing in 1947, Frank Philipp recalls that when he visited the House of Friends in London, the headquarters of the Quakers, he saw pictures of three men in the secretary’s office: Gandhi, Albert Schweitzer and Einstein. ‘I was rather surprised at this combination and asked the secretary what it was that these three persons had in common. Amazed at my ignorance, he informed me: All were pacifists.[34]

In the Einstein Archive at Princeton, Pais has found the following piece by Gandhi, but in German (apparently translated by someone), about Zionism. Einstein, a German Jew who fled to America, supported the ideals of Zionism although he was not in favour of violence in Palestine. This note is undated and it is not clear if it was addressed to Einstein, but its existence in the Einstein Archive suggests Einstein’s interest in Gandhi’s assessment of Zionism. The note has been translated into English by Pais:

The Zionism in its spiritual sense is a noble aspiration, but the Zionism which aims at the re-occupation of Palestine by Jews does not appeal to me. I understand the yearning of the Jew to return to the land of his forefathers. He can and should do that in so far as this return can be achieved without English or Jewish bayonets. In that case the Jew who goes to Palestine can live in perfect peace and friendship with the Arabs. The real Zionism which rests in the hearts of the Jews is an aim one should strive and give one’s life. Such a Zionism is the abode of God. The true Jerusalem is a spiritual Jerusalem. And that spiritual Zionism can be realized by the Jew in every part of the world.[35]

Einstein and Pundit Nehru

The late Indira Gandhi once remarked that ‘My father’s three books — Glimpses of World History, An Autobiography and The Discovery of India — have been companions through life.’[36] Indeed these three books, which Nehru wrote in the midst of his struggles for India’s liberation (and often as letters from prison cells to his daughter), have taught many readers (including this author) about history and India. Nehru was fascinated with modem science; thus he appreciated the significance of Einstein. In Glimpses of World History (1934–35), Nehru refers to Einstein and the theory of relativity, and describes him as ‘the greatest scientist of the day’.[37]

In The Discovery of India, Nehru quotes Einstein: ‘In this materialistic age of ours, the serious scientific workers are the only profound religious people.’ Then Nehru adds a footnote that ‘Fifty years ago, Vivekananda regarded modern science as a manifestation of the real religious spirit, for it sought to understand truth by sincere effort.’[38]

In October 1949, Nehru (then the first Prime Minister of an independent India) visited the USA. It was probably during this trip that Nehru met Einstein and gave him a copy of The Discovery of India.

We have the following letter from Einstein to Nehru dated 18 February 1950, from Princeton, expressing his impressions of Nehru’s book:

Dear Mr Nehru,

I have read with extreme interest your marvelous book The Discovery of India. The first half of it is not easy reading for a Westerner. But it gives an understanding of the glorious intellectual and spiritual tradition of your great country. The analysis you have given in the second part of the book of the tragic influence and forced economic, moral and intellectual decline by the British rule and the vicious exploitation of the Indian people has deeply impressed me. My admiration for Gandhi’s and your work for liberation through non-violence and non-cooperation has become even greater than it was already before. The inner struggle to conserve objective understanding despite the pressure of tyranny from the outside and the struggle against becoming inwardly a victim of resentment and hatred may well be unique in world history. I feel deeply grateful to you for having given to me your admirable work.

With my best wishes for your important and beneficent work and with kind greetings,

Yours cordially

Albert Einstein

(Please remember me kindly to your daughter.)[39]

A Hindu correspondent urged Einstein to embark on a hunger strike (in a Gandhian style) until production of the hydrogen bomb was stopped. On 24 March 1950, Einstein replied:

I can well appreciate that the course of action you suggest in your recent letter seems quite natural to you since you are living among people of Indian mentality. But knowing the mentality of the American people, I am quite convinced that the action which you suggest would not have the desired effect. It would, on the contrary, be considered an expression of unpardonable arrogance.

This does not mean that I do not have the greatest admiration for Gandhi and for the Indian tradition in general. I feel that the influence of India in international affairs is growing and will prove beneficent. I have studied the works of Gandhi and Nehru with real admiration. India’s forceful policy of neutrality in regard to the American—Russian conflict could well lead to an unified attempt on the part of the neutral nations to find a supranational solution to the peace problem.[40]

The last connection we know of between Einstein and Nehru was in 1955. Ronald Clark[41] writes that the occasion for this correspondence was the conflict between the mainland Chinese Communists and the Nationalist government in Taiwan over the islands of Quemoy and Matsu (off southeast coast of China). This conflict could eventually involve the United States as well. Einstein wrote to Nehru for his intervention for a peaceful resolution of this dispute. What Nehru did and whether he replied to Einstein, I could not find a record. Einstein died on 18 April 1955. Nehru continued to be India’s first prime minister until his death in 1964.

Leopold Infeld, Einstien’s colleague and biographer, has concluded his book about Einstein with an imagery involving India that is apt to cite here as a closing paragraph of this article.

In seeking to understand Einstein’s appeal to the imagination of so many of his fellow men, a strange comparison comes to my mind. In a village in India there is a wise old saint. He sits under a tree and never speaks. The people look at his eyes directed toward heaven. They do not know the thoughts of this old man because he is always silent. But they form their own image of the saint, a picture that comforts them. They sense deep wisdom and kindness in his eyes …. Perhaps the real greatness of Einstein lies in this simple fact that, though in his life he has gazed at the stars, yet he also tried to look at his fellow men with kindness and compassion.[42]

Notes

- Philipp, F., Einstein. His Life and Times (translated from the German by George Rosen), Alfred Knopf, New York, 1947 (reprinted in 1972), p. 337.

- Infeld, L., Albert Einstein, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1950, p. 134.

- Clark, R. W., Einstein. The Life and Times, World Publishing Company, New York, 1971, p. 730.

- Pais, A., Subtle is the Lard. The Science and the Life af Albert Einstein, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1952, p. 552.

- Pais, A., Einstein Lived Here, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1994, p. 292.

- Brian, D., Einstein. A Life, John Wiley, New York, 1996.

- Pais (1994, ref. 5, p. 99) quotes this as a private communication with the late Helen Dukas, Einstein’s secretary for more than 25 years.

- Tagore, R., Asia Mag., 1931, 31, 139.

- Einstein, A., Podolski, B. and Rosen, N., Phys. Rev., 1935, 47, ser. 2, 777-780.

- Pais, 1994, ref. 5, p. 5.

- Barrow, J. and Tipler, F., The Anthropic Cosmological Principle, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1986.

- Copy in the Einstein Archive at Princeton, quoted by Pais, ref. 5, p. 105.

- The Modern Review, Calcutta, January 1931, p. 42.

- The American Hebrew, 11 September 1931, p. 351 .

- Quoted in Otto Nathan and Heinz Norden, Einstein an Peace, Schocken Books, New York, 1968, p. 112. This manifesto was also signed by many other well-known scholars and writers including Sigmund Freud, John Dewey, Thomas Mann, Bertrand Russell and H. G. Wells.

- Nathan and Norden (1968), ref. 15, p. 113.

- Chatterjee, R. (ed.), The Golden Book of Tagore: A Homage to Rabindranath Tagore from India and the World in Celebration of His Seventieth Birthday, Kalidas Nag, Calcutta, 1931, p. 374.

- Copy in the Einstein Archive at Princeton, quoted by Pais, ref. 5, p. 108.

- Copy in the Einstein Archive at Princeton, quoted by Pais, ref. 5, p. 99.

- Meeting of Seyyed Jalaluddin Tehrani and Rabindranath Tagore, Armaghan (Persian journal, Tehran). 1932, 13, 108-110.

- Nathan and Norden (1968), ref. 15, p. 98.

- Copy in the Einstein Archive at Princeton University, quoted by Pais, ref. 5, p. 109.

- Record 32:589 in Albert Einstein Archives at the Jewish National University Library, Jerusalem, quoted in Sarojini G. Henry, Gandhi Marg, 1993, 15, 334-345.

- Copy in the Einstein Archive at Princeton, quoted by Pais, ref. 5, p. 109.

- Also Record 32:589 in Albert Einstein Archives at the Jewish National University Library, Jerusalem, quoted in Henry (1993), ref. 23. Henry mentions the date of l8 October, not 10 October.

- ‘Peace Must Be Waged,’ Interview with Robert Merrill Bartlett in the Survey Graphic, August 1935, Nathan and Norden (1968), ref. 15, p. 261.

- Radhakrishnan, S. (ed.), Birthday Volume to Gandhi, George Allen & Unwin, London, 1939. (Mahatma Gandhi. Essays and Reflections on His Life and Work: Presented to Him on His Seventieth Anniversary, 2 October 1939, 2nd edn, 1949, p. 557).

- Einstein, A., Out of My Later Years, Philosophical Library, New York, 1950, p. 240.

- Quoted in Nathan and Norden (1968), ref. 15, p. 467.

- Record 32:609 in Albert Einstein Archives at the Jewish National University Library, Jerusalem, quoted in Henry (1993), ref. 23.

- Record 32:611 and Record 32:612 in Albert Einstein Archives at the Jewish National University Library, Jerusalem, quoted in Henry (1993), ref. 23.

- Quoted in Nathan and Norden (1968), ref. 14, p. 529. Also reported in The New York Times, 19 June 1950.

- Quoted in Nathan and Norden (1968), ref. 15, p. 584.

- Philipp (1947), ref. 1, p. 158.

- Quoted in Pais, ref. 5, p. 109.

- Indira Gandhi, 4 November 1950, foreword to Glimpses of History, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 1982.

- Nehru, J., Glimpses af History, Kitabistan, Allahabad, 1934-35 (reprinted by Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 1952, p. 867).

- Nehru, J., Discovery of India, Signer Press, Calcutta, 1946 (reprinted by Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 1951, p. 558).

- Letter printed on the back cover of Discovery of India (Oxford edition, 1981).

- Quoted in Nathan and Norden (1968), ref. 15, p. 525.

- Clark (1971), ref. 3, p. 626.

- Infeld (1950), ref. 2, pp. 129—130.

(Rasoul Sorkhabi is at Energy and Geoscience Institute, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA. Courtesy: Current Science, Vol. 88, No. 7, 10 April 2005. Current Science is an English-language peer-reviewed multidisciplinary scientific journal. It was established in 1932 and is published by the Current Science Association along with the Indian Academy of Sciences.)