[Excerpted from ‘Breaking Worlds: Religion, Law and Citizenship in Majoritarian India; The Story of Assam’, a report by the Political Conflict, Gender and People’s Rights Initiative at the Center for Race and Gender at UC Berkeley.]

In Assam, the Sangh Parivar (family of Hindu nationalist organizations) has amplified their campaign for prejudicial citizenship for decades. Official discourse has routinely propagated that Bangla-descent Muslims of Assam, many among whom also self-identify as “Miya” Muslims, are “foreigners” and “intruders” who have “illegally” immigrated to India. The criteria for citizenship in Assam are that: (1) An applicant must be an individual who entered Assam before March 1971; and (2) The children of such person(s). Thereby, even if an individual was born in Assam in 1973 and has never traveled out of Assam during the last forty-seven years, they will not be treated as a citizen unless they are able to show that their parents entered Assam before March 1971. Bangla-descent Bangla-descent Hindus of Assam are Bangla origin Assamese (Axomiya, Oxomiya)-speaking Hindus (also, Bengali). They are often identified and targeted based on their last (family) names. Non-Muslims without documentary evidence of their birth may claim to have come from Pakistan or Bangladesh and posit that their documents were seized. This seizure may be evidenced as entitlement to citizenship in India. Muslims, especially Bangla-descent Muslims, may not make such a claim.

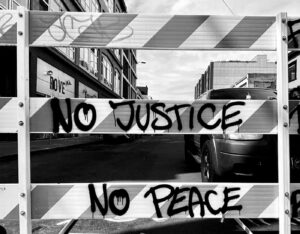

“Original Inhabitants” | “Infiltrators”

The portrayal linking Muslim immigration from neighboring countries to India and Assam and population growth was not based on census data. This narrative has been politicized to create social tension. Vulnerable communities across Assam contend that the present government and majoritarian activists are weaponizing citizenship to manufacture Muslims as the “enemy within.” Central to the plan is to advance the idea of the “original inhabitant,” which is not defined in Indian law. For example, in January 2021, at a rally in Kokrajhar, Amit Shah, stated: “Do you want to make Assam infiltrator-free or not?” The population of Assam was recorded at 31.2 million in 2011. In 2020, while Muslims reportedly constituted approximately 37.1 percent of Assam’s population of 35 million and numbered about 13 million, Bangla-descent Muslims numbered almost nine million and were alleged to be of “Bangladeshi origin.”

Exclusion from NRC

The publication of the draft NRC in Assam in 2018 revealed the exclusion of more than four million persons from the survey rolls. Reportedly, some people were excluded due to spelling errors in their names or inconsistent names in documents. After the draft list was made public, excluded individuals were permitted to submit further documentation proving their citizenship. While a majority were not of Hindu descent, reportedly between one and 1.5 million were Hindus. The exclusion of a large number of Hindus from the 2018 NRC list is presumed to be the foremost reason that changes were made to the citizenship law, and that the Citizenship (Amendment) Act of 2019 was enacted, whereby, in effect, only Muslims would be excluded from citizenship.

The (ostensibly “final”) update to the Assam NRC was undertaken on August 31, 2019. Approximately 1.9 million persons (numbering 1,906,657) were excluded from the 2019 published list, and may potentially lose their citizenship, and face expulsion, exile, and statelessness. The 2019 Assam NRC list reportedly excluded approximately 486,000 Bangla Muslims (25.5 percent of those excluded from the August 2019 NRC list) of a total of 700,000 excluded Muslims (36.7 percent of the excluded); 500,000-690,000 Bangla Hindus (26.2-36.2 percent of the excluded); and 60,000 Assamese Hindus (3.1 percent of the excluded). However, Hindus excluded from the 2019 NRC list are likely to be protected through the 2019 amendment to the Citizenship Act, 1955. Those at risk of loss of citizenship reportedly included thousands of tribal (indigenous), ethnic, and minority communities. Among the latter, individuals including those from indigenous groups number between 240,620 and 670,657 (between 12.6 and 35.2 percent of the excluded). The Assam Border Police too have pronounced certain persons to be “foreigners.” The Election Commission has decreed 231,657 persons as “doubtful” citizens, declaring them “D voters” (“doubtful voters”) and divesting them of voting rights, and has referred their cases to the Foreigners Tribunals.

Assam’s “Foreigners Tribunal”

The Foreigners Tribunal of Assam remains the state mechanism for appeal for persons excluded from the NRC. Individuals may petition the Foreigners Tribunals with requisite documentation validating their citizenship. An appellant is deemed to be either “foreigner” or “citizen” as per the ruling of the tribunal. The process is hard, complex, and arbitrarily and routinely discriminatory. An analysis of 787 Guwahati High Court orders and judgments published by The Wire found that cases before the tribunals took about 3.3 years on average.

On March 16, 2021, the Lok Sabha recorded that there were 300 Foreigners Tribunals in Assam and that the Home Ministry had authorized the establishment of an additional 200. The tribunals routinely lack transparency with respect to principles, standards, and functioning. There is pressure on temporary tribunal appointees to decide against citizenship applications brought before them. Individuals who receive an unfavorable judgment from a tribunal have the sole option of appealing to the Assam High Court (unaffordable for many), followed by the (small) possibility of approaching the Supreme Court. As of October 2019, it appears that the cases of 468,905 persons have been brought before the Foreigners Tribunals. Of these cases, reportedly 136,149 people were declared to be “foreigners.” Community leaders, lawyers, and journalists state that of the 136,149 persons declared “foreigners,” 70 to 80 percent (90,306 to 103,207 persons) are reportedly Muslims Among these Muslim individuals, about 90 percent (81,275 to 92,886 persons) are reportedly Bangla-descent Muslims. The results are gendered. In 2019, 290 women were reportedly declared “foreigners.” In December 2020, 140,050 cases were pending before Foreigners Tribunals in Assam. Community knowledge holders say that most of the above individuals are local inhabitants with documentary evidence of belonging and citizenship. Further, the NRC may refuse citizenship to Muslim asylum seekers and refugees. Civil society leaders contend that such persons, and the few who may be “illegal” (undocumented), must be entitled to asylum.

By February 2019, 63,959 individuals in Assam had been stipulated as “foreigners” reportedly through ex parte proceedings, where a tribunal issued a judgment in the absence of the accused. Individuals can apparently intervene in these proceedings in an attempt to influence the outcome. In September 2019, a Muslim family with land documents dating back to 1927 found that all members of their family were not on the NRC due to: “an objection filed [apparently anonymously] by someone against their inclusion in the final draft.” It is unclear who may file bad-faith objections or how they may be held accountable. Reportedly, approximately 250,000 such objections have been made, mostly anonymously. The Foreigners Tribunal procedures are reportedly manipulated by officials and others to extort bribes and discipline and criminalize targeted community members. Such actions have caused economic hardship. People have sold their possessions or used up their savings on defense lawyers. The mental health of innumerable people has been impacted, as exemplified by a Muslim woman who reportedly committed suicide after her husband’s citizenship case drained the family of their property and money.

Foreigners Tribunals: 38 Cases

A review of 38 cases comprising 37 Foreigners Tribunal orders and one affidavit attests to the capricious and hostile nature of the proceedings. In numerous instances, the state’s legal representative does not even appear, often to the detriment of the person appearing before the tribunal. In 51 percent of the analyzed orders, the state’s representative was not present for a part or the entirety of the proceedings. In 30 percent of the orders, a document submitted by the individual was rejected by the tribunal member because the official who had issued the document was not present at the tribunal to testify to the document’s contents and authenticity. In 11 percent of the orders, the tribunal member dismissed a document due to the location of the state emblem embossed on the document. In 38 percent of the orders, the tribunal member mentioned name or age discrepancies in the documents submitted, and in numerous instances, this impacted the ruling on an individual’s citizenship status.

Detention, Criminalization

Once declared a “foreigner,” an individual may be held in detention. Immigration detention centers are often locally referred to as “concentration camps.” Detention serves to criminalize and confine those deemed “illegal foreigners.” Without established limits or protocols for ethical resolution of the matter, detentions can be prolonged or indefinite unless deportation ensues. Currently, India operates thirteen detention centers, and others are being constructed to assumedly hold “undocumented” individuals. The six detention centers in Assam are operated within existing jails and reportedly confine those declared to be “foreign nationals” by the Foreigners Tribunals. A detention center to hold 3,000 persons is reportedly being constructed at Goalpara in Assam. It is India’s largest and first detention center for “illegal” immigrants.

In November 2019, 1,043 persons were reportedly being held in detention at six centers in Assam. Approximately 20 to 25 percent of them were reported to be women. Some young children were also detained. By March 2020, it was reported that 3,331 persons had been held in the six detention centers in Assam. As of April 2020, at least 30 persons have died in Assam’s detention centers since 2009, most due to health conditions and others under mysterious circumstances; 16 reportedly of Hindu descent and 14 of Muslim descent; three among them women. In May 2019, the Supreme Court ordered that those regarded “non-citizens,” and detained for more than three years, be conditionally released. Despite the apex court’s directive, people continued to be detained. In February 2021, it was reported that some detention centers were cramped, lacking in basic hygiene and sufficient food. Earlier, detainees have organized hunger strikes. At the end of May 2021, reportedly 170 detainees remained incarcerated, while in July 2021, the reported number of detainees was between 177 and 181. In June 2021, local communities and lawyers noted the number of incarcerated detainees to be approximately 500.

“Definitive List,” COVID-19

The delivery of notifications to those who had been excluded from the 2019 NRC was reportedly scheduled to commence on March 20, 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic and the floods in Assam in 2020 led authorities to postpone the distribution of NRC notifications. The hearings of the Foreigners Tribunals were disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, which also delayed the activation of 200 new tribunals. In December 2020, a state official alleged that the Assam NRC list of August 2019 was a “supplementary” record and that a definitive list is due to be published. On May 13, 2021, the Assam NRC Authority approached the Supreme Court seeking re-verification of the NRC list (emphasizing districts bordering Bangladesh and with significant Muslim populations), appealing that “illegal voters” be purged from voter lists. Earlier, on April 1, 2021, the central government reportedly ordered the Assam state government to send “rejection” notifications to persons who were not on the NRC, triggering the 120 days to launch an appeal.

Psychosocial Health and Suicide

The experiences of those who are forced to prove their belonging have exacerbated mental and emotional strain. The processes to prove citizenship, the resultant and imminent dangers, the actuality of detention, and the prospect of deportation have injuriously impacted the psychosocial and inter-generational health of individuals and communities. This is instantiated through health crises, including sleep irregularities, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), suicidal ideation, and suicide. Between July 2015 and October 2020, between 38 and 42 persons apparently committed suicide in Assam in connection with the revocation of their own or a relative’s citizenship rights. In research into 38 instances where persons committed suicide, reportedly: 20 individuals were of Muslim descent, 16 were of Hindu descent, and two were from tribal/indigenous communities. Seven persons were women, six of whom were of Muslim descent.

Presumptive Statelessness

The dread of would-be dispossession is tangible for millions of Muslims across Assam, in its villages and cities, the char areas (river islands), and World Heritage sites. Muslim communities say that the implementation of exclusionary citizenship is desecrating the very structure and composition of social and political life. While the tribunals have not resulted in increased deportations thus far, they have contravened the rights and entitlements of countless residents of Assam and proclaimed innumerable citizens to be “foreigners,” and therefore, presumptively stateless. As a woman interviewee noted: “We are terrified because we are Muslim.” The rules of the CAA are yet to be announced by the parliament. However, the BJP national government issued a notification on May 28, 2021, reportedly operationalizing prejudicial citizenship in certain areas in the states of Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Haryana, Punjab, and Rajasthan. On July 27, 2021, it was reported that the rules of the CAA would not be announced by the parliament until January 9, 2022.

(Courtesy: The Wire.)