A quarter century ago, I was working with beggars in Baroda. Initially, I was trying to find out how many beggars there were in the city and how they formed a community. It was natural, therefore, for me to form deep friendships with many of them. In summer, in order to escape the scorching heat, they often used to come to my little office and spend time there, helping me with small tasks like sealing envelopes or dusting furniture.

An old woman, originally from Andhra Pradesh, was one of them. Her working sons had abandoned her. She was not literate; and she was not very fond of long conversations. One day, as she sat down on a chair, I pointed to a photograph on the wall and asked her, “Do you know who this man is?” Without pausing for a moment, she replied, “Mahatma Gandhi”. Quite frankly, I had not expected her to know since she had never been to a school. I was surprised; but what surprised me more was that she spoke at some length on him—as much as she knew—and concluded with the words, “A real man, all others are fake.”

What was it in Gandhi that touched the soul of India, that made him almost the sub-stratum of every Indian’s subconscious? This incident took place some 55 years after his death. Even across such a distance in time and such a great social distance between him and the Andhra woman in Gujarat, he stood on his own feet, without the need of an anchor to introduce him, without an interlocutor, without media, without a WhatsApp factory to prop him up.

Moral ethos

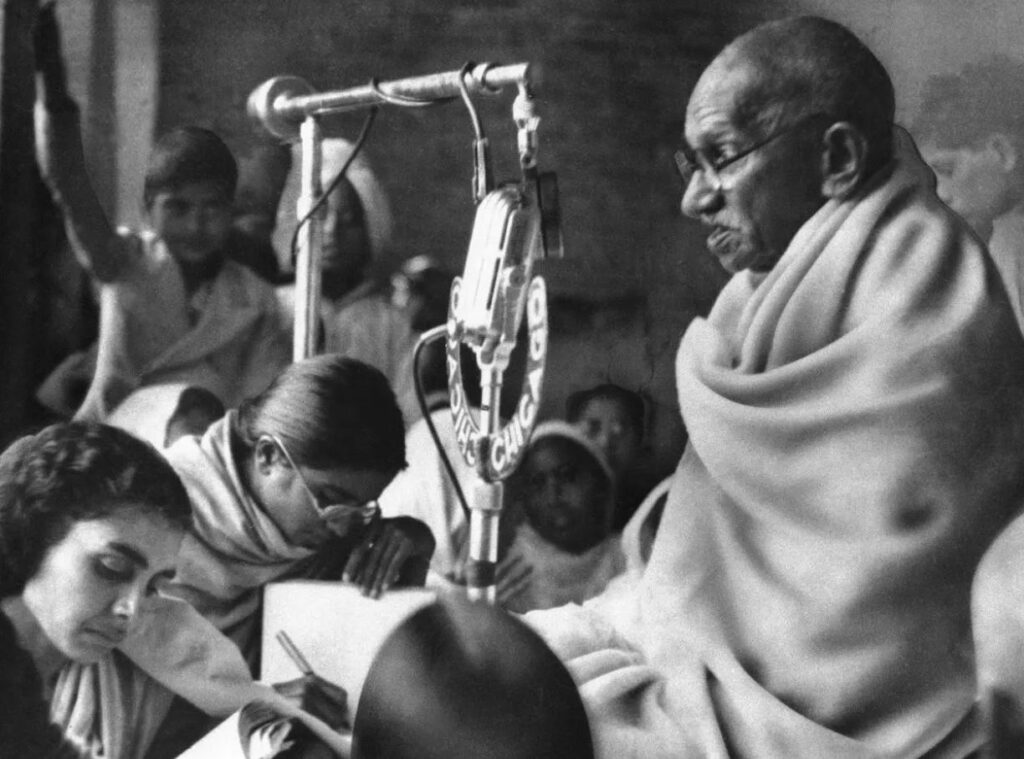

“A man is not called wise because he talks and talks again; but if he is peaceful, loving and fearless, then he is in truth called wise,” is a well-known dictum of Gautama Buddha. The most outstanding testimony to the permanence of this observation was the life of Mohandas Gandhi—two and a half millennia after the Buddha—and the moral ethos he created in the Indian subcontinent. Gandhi was already a legend when he entered the Indian political scene and was no less than a living myth when he was brutally assassinated. He did not write bulky books on political philosophy or ethics, yet his thought reached millions and transformed innumerable lives.

The magic that Gandhi was, whether it sprang from his immense moral authority or from the accident of his location in history, has not ceased to amaze his biographers, commentators, followers, and even his vicious detractors. It would indeed be impossible to count the number of times his name is mentioned in learned books, essays, public lectures, political discourse, dramatic productions, films, art works, family conversations, and in the thoughts of billions of persons over the last hundred years.

One cannot think of any leader, thinker, activist, saint, artist, sportsperson, scientist, sovereign, or writer whose fame has acquired the dimensions that Gandhi’s has. After Gandhi was killed by the bullets of an assassin, the world, stunned by the brutality of the act, reacted with tributes that can fill many printed volumes. The best among them came from the most outstanding scientist of the 20th century, Albert Einstein. Generations to come will scarce believe that such a one as this ever in flesh and blood walked upon this earth, Einstein wrote.

At the spot where Gandhi was killed, the backyard garden of Birla House on the street named after the date of the assassination as the Tees January Road, is this famous epitaph, engraved on rock, reminding the mythical dimensions of the incredible phenomenon that Gandhi was. The other thing, even more overwhelming, is the stark simplicity of the memorial there. One can walk to the very point where Gandhi was hit by the bullets and imagine oneself, for a brief moment, being with him, even being him.

The ease of access to Gandhi and everything about Gandhi cannot be captured in words. It is the same experience when one visits the Sabarmati Ashram where Gandhi spent over a decade of his life. The house in which he lived there was designed by him. The spaces in that house, serene and beautiful, just cannot be divided into ‘inside’ and ‘outside’. They merge completely into each other. It reflects his person as probably nothing else associated with Gandhi’s life does. The Mahatma was, and will remain through ages, this unique combination of his ability to make you feel so close to him and the vastness of his thought and action that gives him a superhuman, mythical dimension.

I met the Andhra woman in 2002, the year of the genocide which will make future generations of Gujaratis hang their heads in shame. Seventeen years later was the 150th birth year of Mohandas Gandhi. During those 17 years enough had been done by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) propaganda machine to malign his image. The image of this phenomenal barrister was made to appear on government publicity posters only in the form of his spectacles, with a latrine in the background. By then, the regime had managed to divide Indian people in the name of religion. Mob-lynching of Muslims and Dalits had become the order of the day. Cow-protection vigilantes had found unchecked space for intimidation of innocent persons. The national media, itself intimidated, particularly TV, had made these incidents part of their daily diet. Prominent rational thinkers such as Narendra Dabholkar, Govind Pansare, M.M. Kalburgi and Gauri Lankesh were killed by bullets. Law-keeping agencies were busy suppressing any and all dissent. Social media was used to troll opponents on an industrial scale.

If this was the general atmosphere in India, the international scene was no different. The extreme Right in Europe was in ascendency. Countries such as Turkey, Egypt, Brazil, Russia, and China had come under autocratic rule. Democratic governments in Germany, Italy, Spain, and France had to seek the support of the right wing in order to function. Donald Trump had won the presidential election in the United States and an era named ‘post-truth’ was rapidly unfolding.

Post-truth realities

It is hardly surprising in such an atmosphere of ‘post-truth and violence’ that people in and outside India started thinking about the greatest votary of truth and non-violence. The memory of Mahatma Gandhi, therefore, started resurfacing like a tidal wave in the minds of those who cherish the idea of democracy, decency in public life, and social harmony. It was common to see even Leftists, Liberal Democrats, leaders of workers’ unions, artists, writers, singers, and ordinary people returning to Gandhi. Some of the Ambedkarites, normally allergic to Gandhi, too, started expressing the desire to look at him with a lesser degree of contempt. Gandhians who had reduced ‘Gandhism’ to empty rituals, too, started articulating the need for rediscovering Gandhi. Several social media groups were formed on the Internet and later, WhatsApp, to discuss the ideas of Gandhi within wire-net communities of like-minded groups. All of these were coming closer to one another in various degrees and voicing their fear that the legacy of Gandhi and Ambedkar would be claimed by the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh (RSS) as its own. Surprising it was for the dispensation that the more it tried to wipe out Gandhi’ s memory from the public memory, more spontaneously it resurfaced.

The recent move of the NCERT to drop the Gandhi assassination out of its history textbooks shocked millions, although not all of them expressed their dismay in an organised way. On the day I read about the NCERT move, the excited face of the Andhra woman flashed in my memory. As I remembered her face and her excited words of admiration for Gandhi, I said to myself, “Gandhi shall live on, textbook or no textbook. He was, as the woman had said, ‘the real’ one, while many other fake ones will stay around only so long as propaganda props them up. I want to thank the NCERT authorities in advance for proving, as the world shall witness in some future, that the Mahatma’s memory just cannot be extinguished. He was and is a Mahatma because his truth and non-violence touched the conscience of everyone. That is a question of conscience and currently somewhat outside the grasp of the intimidated and servile bodies that crawl where every school-going child expects them to stand.

(Ganesh Devy is Obaid Siddiqi Chair Professor, National Centre for Biological Sciences, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Bengaluru. Courtesy: Frontline magazine.)