Perhaps the best possible thing we could acknowledge being is a “divided nation.” Failing to do so justifies — or at least avoids noticing — all manner of violent cruelty and repression in the name of so-called democracy, from the jailing of whistleblowers who reveal U.S. war crimes and global criminality, to the lynching of men and women of color . . . to the waging of endless war.

Oh, and so much more!

“I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America, and to the empire it purports to be (because it’s the greatest country in the world), one nation under the God of Money (who happens to be a white male), with liberty and justice for a few — and probably not for you or your parents, little kid!”

This is the pledge of allegiance we don’t teach to schoolkids, but it’s the one under which they live — some more than others, of course.

Considering the specific chaos of the moment — the hearings on the January 6 mob attack of Congress, the latest trillion-dollar budget proposal for war and global annihilation, the recent sentencing of whistleblower Daniel Hale, the remarkable spate of voter suppression laws being passed by state legislatures around the country, just to name a few — let’s crack open that word, “democracy,” and ponder its actual meaning.

Are we a democracy? I’d have to say both yes and no. That’s because democracy is a paradox. It’s the opposite, and indeed the enemy, of power, and those who possess power often think they have no choice but to hate and oppose its emergence, even as they blather its clichés. Perhaps democracy’s biggest threat is the ease with which the word can be exploited for the purpose of public relations. Those in power can claim, gloriously, to be spreading democracy as they bomb and massacre their enemies, or as they make sure their potential opponents are denied the right to vote.

But if someone steps up and exposes “classified” government actions, which are hidden from public view because they are morally, shall we say, controversial, that person often faces serious punishment. But taking that risk and stepping forward, like Edward Snowden, Chelsea Manning, Reality Winner, Julian Assange, is an act of democracy, in the same way that Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her seat on the bus in 1955, in defiance of the law of the day, was an act of democracy.

Democracy takes courage! Democracy is a tool of human creativity, a.k.a., evolution. We change and evolve only when the status quo is interrupted, which often happens only in defiance of those currently in power. And when an act of democracy occurs, the government often does everything it can to control and mitigate the “damage.”

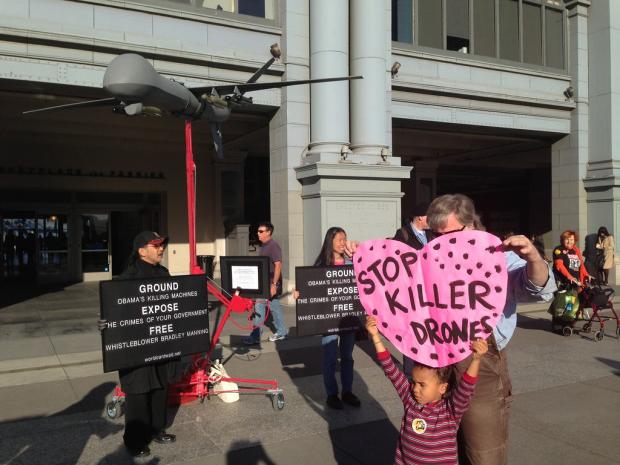

Thus Daniel Hale, a National Security Agency intelligence analyst who passed on classified information to a journalist about the U.S. drone assassination program — specifically about how many untargeted civilians wound up being killed — was recently sentenced to 45 months in prison, having been charged with endangering national security. What was not officially on trial, of course, was the drone warfare itself; that was classified and not supposed to be challenged or interrupted. The government policy amounted to: Take our word for it! We’re protecting your security.

To the extent that such authority prevails, we’re not a democracy, any more than we were a democracy when, in the 1850s Dred and Harriet Scott failed to win their freedom from slavery in the U.S. judicial system. And they were the ones on trial, not the system of slavery itself, even though, at the core of democracy, there is the awareness that all humans are equal, that all lives are sacred, that there are no subhumans and that no one is the property of another.

But, on the other hand, we were a democracy then — however flawed — to the extent that many Americans helped the Scotts with their case, both financially and legally, and the trial transcended the American legal system and entered history as a significant step in the abolition of slavery.

One crucial takeaway from this is that democracy digs a lot deeper into the social structure than giving people the right to vote. We didn’t vote slavery out of existence. And while we eventually abolished it — basically, for strategic purposes in the midst of a horrific war — we have not transcended a national belief in white supremacy. We have not transcended the urge to have power over others: the urge to wage wars, the urge to wall off our borders, the urge to possess nuclear weapons, the urge to extract every last resource from our living planet and avoid thinking about the consequences of doing so.

And the right to vote, while it is something I value, will not be our primary way of dealing with any of the above issues. With a few exceptions, voting — especially at the national level — winds up being the right to make a disappointing choice between a tepid moderate and a full-on believer in (white) nationalism and the rights of rich people. Claiming the right to vote, via the women’s rights or the civil rights movement, has a far bigger impact on creating what kind of society we are than merely putting an X in a box beside someone’s name.

When I proclaim a belief in democracy, this is what I mean: the right to truly participate in the creation of our world. If it weren’t for democracy, we could easily be an undivided nation — united, with a shrug, in our acceptance of slavery, or at least in the necessity of whites-only drinking fountains.

(Robert Koehler is a Chicago award-winning journalist and editor. Article courtesy: CounterPunch.)