After nearly a decade of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government, the country’s prime mover of people, the Indian Railways, are costlier to use, shoddier in quality, carry fewer passengers—but trains are packed with fewer seats for second-class passengers—and are losing more money, according to our review of 20 years to 2023 of data on non-suburban travel.

Some highlights vis-a-vis 2013-14:

- 32% fewer passengers in 2022-23

- 108% more expensive overall for passengers in 2021-22

- Unreserved sleeper-class travel over four times more expensive in 2021-22

- Share of second-class seats & berths down 13% in 2022-23

- Overall speed of trains largely the same

- Punctuality averaged below 80% (2016-2020) and has stayed below the target of 95% (2016-2022).

The Railways are increasingly oriented towards premium trains and privileged, air-conditioned (AC) passengers, while ordinary Indians pay more for a poorer travel experience. Yet, the Railways are worse off financially than in the tenure of the previous United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government, with its surplus declining 80% between 2013-14 and 2022-23.

Our study of 20 years of data reveals that the Railways’ re-orientation away from ordinary passengers did not begin with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government but accelerated substantially during his administration.

The data include statistics on non-suburban travel between 2005 and 2022 published by the directorate of statistics and economics of the world’s second-largest railway network by passenger-kilometres, supplemented with other public information over the past 14 years, including from the government auditor, the comptroller and auditor general (CAG), and the Parliament of India.

These data provide context to a slew of transformational claims made by Modi’s government, including over 50 new Vande Bharat trains costing over Rs 100 crore each, a Rs 1.6 lakh crore Mumbai-Ahmedabad bullet-train line under construction and the Amrit Bharat programme to revamp 554 stations.

The BJP has promised three more bullet trains in its manifesto and 4,500 Vande Bharat trains by 2047. The latest public announcement came on 12 March 2024, when Modi announced developmental projects in his home state, Gujarat, where Rs 85,000 crore of over Rs 1.06 crore he promised were linked to the railways.

Speaking in Ahmedabad on the same day, Modi, seeking a third term as Prime Minister, accused governments since Independence of sacrificing the Railways to “political interests”.

“I am giving a guarantee to the country that in the next five years, they will see a transformation in Indian Railways that they couldn’t have imagined,” said Modi. “Today, unprecedented reforms are taking place in the railways.”

The data do not currently back these claims, as we said, and even though the Railways have cut costs and raised prices, finances appear to be worsening.

Packed Trains

A few weeks after Modi’s announcement in Ahmedabad, and not for the first time over the past year (see here, here, here and here), social media were awash with videos and images of passengers complaining of overcrowded coaches, occupying aisles and toilets and being unable to board trains despite confirmed reservations.

These videos and images confirm one of our main findings, that the Railways have slashed the share of second-class seats and berths in trains.

Some cases that reflected the decline in space and seats:

- Up to 18 women fainted from suffocation over four months to February 2024 in just one train, Mathrubhumi reported.

- On 13 April 2024, Rachit Jain, complained on X that his sister, with a confirmed seat in a three-tier AC coach, faced such chaos and over-crowding at the time of boarding that her child got left behind on the platform. She was injured when she jumped from the moving train.

- On 18 April, the video of an angry man with a supposedly reserved seat breaking the glass door of an overcrowded AC coach that he had been locked out of on the Kaifiyaat Express from Old Delhi to Azamgarh, Uttar Pradesh, went viral on X.

- On May 24, Vijay Kumar complained on X that he and his family had to fight to board the 3-AC bogie of Kamakhya-Delhi Bramhaputra Mail at Patna. Such was the crowding of general passengers in the coach, that they could only access six of their eight confirmed, reserved seats. He also tweeted that the Railway helpline opened and then closed his complaint without any resolution.

On 20 April, the Railways, reacting to one of the videos, tweeted, “Please don’t malign the image of Indian Railways by sharing misleading videos.”

Four days later, union railways minister Ashwini Vaishnaw promised a confirmed seat for all passengers in the next term of the Modi government, an assurance he had made in October 2023 too.

The Indian Railways are the world’s fourth-largest by rail track, 68,043 km by 2021-22, the last year for which the Railways published such data.

The Railways run “12,000 trains to carry over 23 million passengers per day connecting about 8,000 stations spread across the sub-continent,” according to a 2015 white paper published by the ministry of railways.

Ministers and officials routinely proclaim the Railways to be the backbone of the country’s economy, its lifeline, and the thread that unites the country.

Richer Passengers, Premium Trains

However, shrinking second-class space, escalating costs of travel—through increases in base fares, stiffer cancellation penalties and the elimination of many concessions—has likely driven passengers out of trains.

Specifically, ordinary, second-class passengers have been increasingly squeezed out of trains in the Modi era, shows data over 20 years.

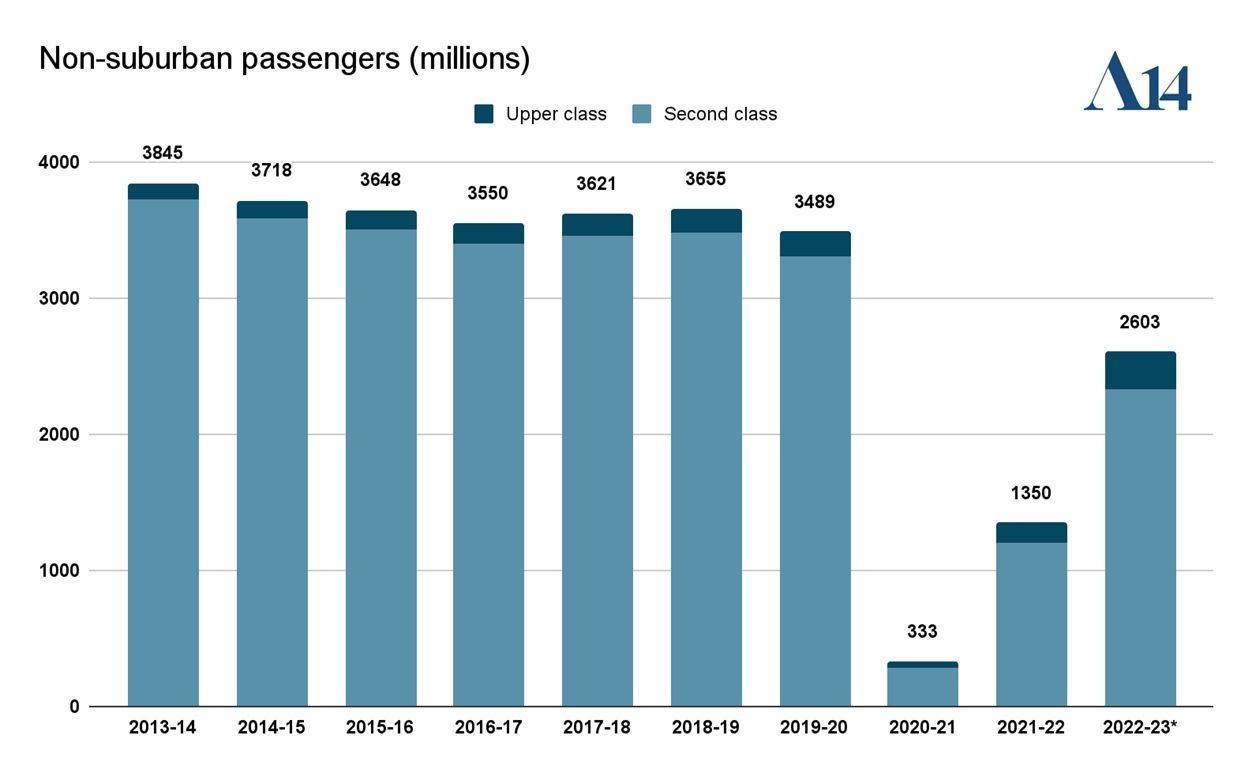

After nine years of nearly 7.4% annual average growth during the UPA government, peaking in 2012-13 at 3.8 billion, each year from 2013-14 saw fewer second-class passengers.

Between 2013-23, the number of second-class passengers declined 5% each year on average, with passengers plummeting from 3.8 billion in 2012-13 to 2.3 billion in 2022-23.

Upper-class travel, which includes AC first class, non-AC first class, AC 2-tier, AC 3-tier, AC economy, and AC chair car, has grown steadily over the past two decades, except during the 2020-2022 years of pandemic-related lockdowns.

*The data for 2022-23 are provisional.

The overall loss of passengers is also damaging for the environment given the Railways’ superior energy-efficiency over roadways.

Fewer Second-Class Seats

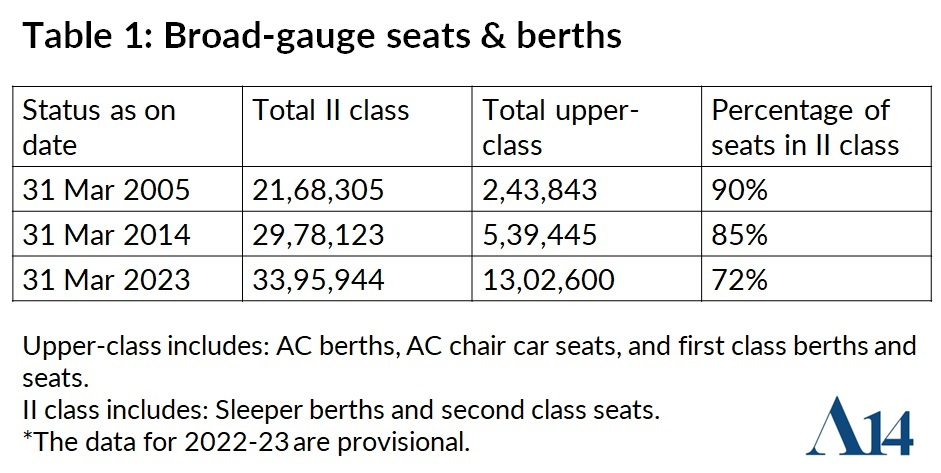

The total number of seats between 2004-2023 have increased, but second-class seats and berths have declined as a proportion of all seats and berths in UPA and NDA governments (see Table 1).

Between 2005 and 2014, second- class seats grew 37%, but only 14% between 2014 and 2023 . In contrast, upper-class seats grew 121% between 2005 and 2014 and 141% between 2014 and 2023.

As on 31 March 2014, second-class seats and berths made up 85% of the available seats on broad gauge trains, while upper-class seats and berths were 15%. By 31 March 2023, upper-class seats had risen to 28% of available seats in broad-gauge trains and the share of second-class seats and berths had fallen to 72%.

The decline in second class seats is the pattern underlying the anecdotes (see for example: ‘Ticketless’ Passengers Occupy AC Sleeper Coach On Train; Railway Seva Reacts, April 17, 2024, https://www.news18.com) of unreserved passengers being forced to take up space in reserved bogies, including, at times, even in a premium AC first-class coach (see for example: “Woman Shares Video Of Ticketless Passengers In Train’s AC Coach, Railways Responds”, December 19, 2023, https://www.ndtv.com).

Over the two years to 2024, there have been reports (see for example: “Southern Railways’ popular trains to soon have just two sleeper coaches”, 11 July 2022, https://www.newindianexpress.com; “Sleeper coaches in Malabar and Maveli Express trains cut down”, 11 September 2023, https://english.mathrubhumi.com.) about the Railways replacing sleeper-class coaches with AC coaches on popular trains. When that happens, passengers must either pay more for a higher class AC seat or crowd into the fewer sleeper-class coaches by paying a penalty or abandon trains.

The promotion of AC travel appears driven by commercial logic rather than that of a public service, Naina Masilamani, member of the divisional railway users’ consultative committee, Chennai, told The New Indian Express in July 2022. A CAG report said AC-3 tier and AC chair car were the only two profitable classes of passenger travel in 2016-17.

How Travel Became Costlier

The price of a train ticket is the sum of base fares and various fees and surcharges, such as reservation fee, superfast surcharge and tatkal (immediate) charges.

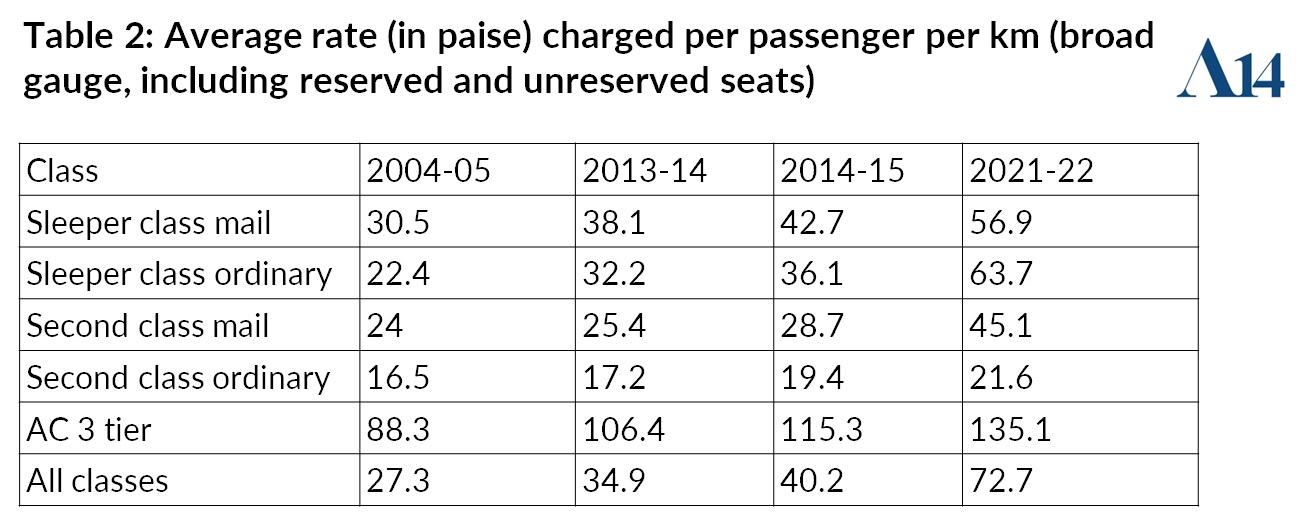

For sleeper-class travel, the average rate charged per passenger for each km of travel increased 33% for mail and express trains and 76% for ordinary trains, between 2014-15 and 2021-22—the corresponding increase between 2004-05 and 2013-14 was 25 and 44% respectively (Table 2).

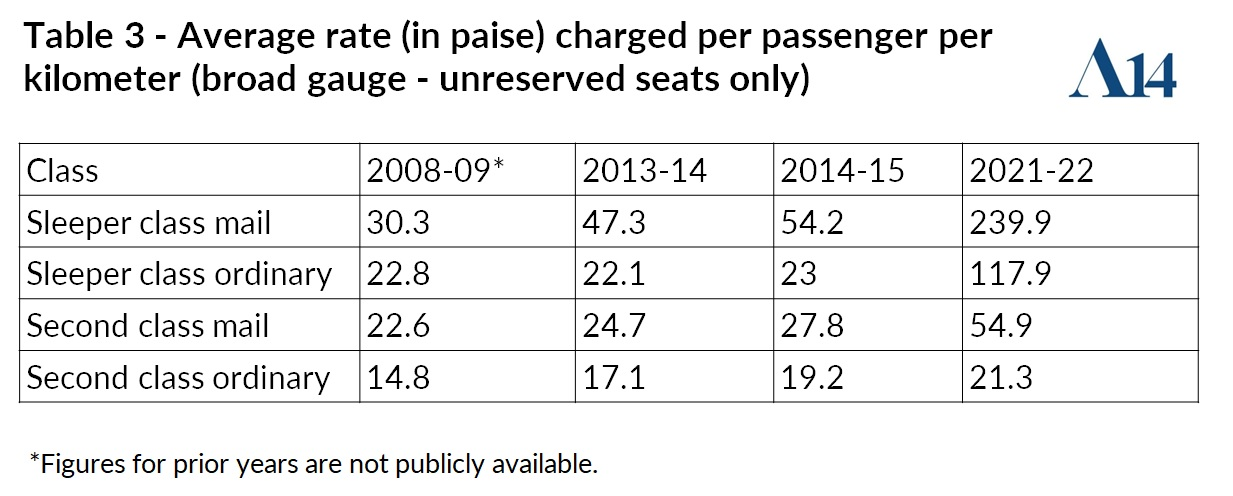

Paradoxically, the cost of sleeper-class unreserved travel—the lifeline of poorest Indians—has risen by 343% in mail and express trains and by 413% in ordinary trains (Table 3): an average annual increase of 24% and 26% respectively, compared to the average consumer price inflation rate of about 5.5% between 2012-22.

The Railways earned more per passenger per km from sleeper-class unreserved travel in mail and express trains than from much better-off passengers traveling 3-tier AC, for which the UPA government had increased rates roughly as much (20.5% overall between 2004-05 and 2013-14) as the NDA (17% overall between 2014-15 and 2021-22).

Until 2012, for nearly nine years, base fares did not change— and Lalu Prasad Yadav as the railway minister between 2004 and 2009 slashed fares in 2008-09. In 2012, fares were increased for 2-tier AC and AC first-class passengers.

There was a hike across all classes in 2013, a further hike of about 14% soon after the NDA came to power in 2014 and another hike effective 1 January 2020.

Building On An UPA-II Legacy

The impact of fare increases on passenger traffic was visible by 2014.

Passengers traveling up to 50 km—more than 55% of Railway traffic —were opting for road travel because of fare rises, the Railway Board reported in 2014. It specifically identified the Bengal-Odisha border and parts of Kerala, Gujarat, Jharkhand and Madhya Pradesh as regions where fare increases led passengers to abandon trains.

Yet, the Railways have increased travel costs directly and indirectly since.

The base fares for newer trains are higher. For instance, the base fares for Antyodaya trains, long-distance fully second-class trains are 15% higher than those of ordinary mail/express trains.

Similarly, fares for the Gatiman, Tejas and Vande Bharat trains are 20-45% more expensive than the older Shatabdi trains, which are more expensive than ordinary mail or express trains.

In 2016, the Railways also introduced “flexi-fares” for Rajdhani, Shatabdi and Duronto trains: increasing by up to 50% depending on occupancy. Though the Railways have tweaked the scheme a few times (see here and here), in November 2023, fares in certain trains went higher than air fares during festival rush.

After October 2022, the Railways re-designated many passenger trains—which stop at nearly all stations—as express special trains. There was often no actual difference in speed, but passengers had to pay nearly double for the same service.

In February 2024, after reports surfaced again about this measure, the Railway Board reverted to previous fares but without revoking the re-designation of express trains.

The Cancellation of Concessions

Over the last decade, the Railways have made cancellation penalties and concessions increasingly restrictive.

Passengers can get a full refund, less clerkage charges, if they cancel a wait-listed reservation up to 30 minutes before departure. While the UPA in its second term raised clerkage charges from Rs 20 to 30 (or 50%) in 2013, the Modi government, in November 2015, doubled it from Rs 30 to Rs 60.

These charges are effectively a penalty on passengers for a service denied to them.

With a declining share of second-class seats, more passengers end up with waitlisted tickets, which do not get confirmed.

A former railway official told The Hindu that the Railways were offering too many waitlisted seats: 600 waitlisted seats in an 18-coach train with 720 sleeper-class seats. In 2022, the Railways earned Rs 439 crore through cancellation of 46 million waitlisted tickets.

The Railways used the Covid-19 pandemic as another opportunity to increase earnings by suspending all concessions, except 22 categories meant for students, patients and disabled travelers. The removal of concessions for senior citizens has been reported (see for example: “Concession for senior citizens may not be restored soon”, December 15, 2022, https://www.thehindu.com.), but the list below mentions other categories:

- Unemployed youth en route to interviews for jobs in public sector undertakings

- Unorganised-sector workers with monthly incomes less than Rs 1,500 traveling up to 150 km

- Industrial workers awarded the Prime Minister’s Shram Award

- Farmers, milk producers and industrial labourers (with certain conditions)

- Sportsmen en route to international, national and state tournaments

- War widows, widows of policemen and paramilitary personnel killed in action against extremists and terrorists, widows of martyrs of Operation Vijay in Kargil in 1999, widows of Indian Peace-keeping Force (IPKF) personnel killed in action in Sri Lanka

- Artistes—theatrical, musicians, dancing, magicians—travelling for a show

- Nurses and midwives

- Press correspondents accredited to headquarters of central and state governments/union territories/districts, travelling on work

A 2019 CAG analysis showed that between 2015 and 2018, 6.3 million passengers, including students, claimed concessions of about Rs 217 crore or about Rs 72 crore per year, about 0.2% of annual average passenger earnings. Since concessions for students remain, savings for the Railways will be lesser than this.

By way of comparison, the outstanding dues owed to the Railways by state electricity boards alone was Rs 784 crores in 2017, according to an August 2017 report of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Railways.

Through these big and small changes, the Railways have boosted their earnings, despite falling passenger traffic. In April 2016, the Railways informed the Parliamentary Standing Committee that “despite the negative growth observed in originating passengers, the (sic) passenger earnings have witnessed a positive growth all along”.

Trains Speed Up By 0.4 Kmph in 8 years

The quality of service across many metrics remains the same, if not worse, over the past decade.

In a railway budget speech on 25 February, 2016, the railway minister Suresh Prabhu announced Mission Raftaar (Mission Speed), which targeted to increase the average speed of mail and express trains to 75 kmph by 2021-22.

The average speed of mail and express trains increased only by 0.1 kmph, from 50.9 kmph in 2015-16 to 51 kmph in 2021-22.

Data available over eight years of NDA rule reveals that the average speed of mail and express (broad gauge) trains was 51 kmph in 2021-22, as compared to 50.6 kmph in 2013-14. Over 10 years of UPA rule before that, the average speed of mail and express trains increased by 3.6 kmph.

The speed of ordinary passenger (broad gauge) trains went up from 36 kmph in 2013-14 to 37.7 kmph in 2021-22.

Did travel time reduce? A 2021 CAG analysis showed that in 2012-13, it took 19 hours and 52 minutes to travel 1,000 km. In 2019-20, the same journey took 19 hours and 47 minutes.

This improvement of 5 minutes is calculated by the train time table, as is done for speed and audits. Calculated by real-world train timings, the picture is considerably worse.

The Railways started making public punctuality data in 2016-17. India is generous in its punctuality threshold. A train is counted as late only if it reached its destination 15 or more minutes after its scheduled arrival.

In other words, if a train is late by hours at intermediate stations, but reaches its destination less than 15 minutes after its scheduled arrival, it is not considered as being late.

In 2017-18, 30% of trains ran late, and, as per a 2020 CAG report, over half of India’s express trains ran late between 2016 and 2019. A 2017 CAG found that a few trains did not ever reach their destinations on time.

A 2018 CAG report said more than 60% of Rajdhani, Duronto, and Shatabdi services, all premium trains, were late. More recent reports find the Railways prioritising premium trains, such as the Vande Bharat, at the expense of other trains, which are delayed and made slower.

Despite an investment of Rs 2.5 lakh crores in infrastructure between 2008 and 2019, punctuality improved only 0.18%, partly because, as the Railways informed the CAG in 2021, there was a 20% increase in train services between 2012-13 and 2018-19.

Railways Are Poorer

10 years of NDA rule has left the Railways in worse financial health than the previous decade. One important metric for financial health is the operating ratio, which measures operating expenses against revenue: the operating ratio is the amount of money spent by the Railways to earn Rs 100.

A high operating ratio, which leaves the Railways with a smaller surplus for investments, has been a concern for some decades.

In 2000-01 the operating ratio reached a high of 98.3%, which meant the Railways spent Rs 98.3 to earn Rs 100. It steadily improved and during the regime of Lalu Yadav, it came down to 76% in 2007-08.

Yadav managed to lower the operating ratio without increasing base fares for passengers.

The operating ratio rose again and reached 93.6% in 2013-14, the last year of the UPA government.

The operating ratio improved a little again to touch 90.5% in 2015-16, after which it has persistently stayed over 96%. In 2021-22, the Railways recorded an operating ratio of 107%, meaning they spent Rs 107 to earn Rs 100.

The Railways attributed the poor operating ratio to pandemic-related disruptions, but the operating ratio was already 97.3% pre-pandemic and went up marginally to 98.2% in 2022-23, the last available data.

In a 2020 report, the CAG revealed an accounting measure that allowed the Railways to “window dress” its finances: reporting advance freight earnings in a financial year for the next year.

This began in 2017-18 and continued in 2018-19, despite a CAG warning. Correcting for such accounting adjustments, the Railways’ operating ratio breached 100% in 2018-19 and has not come down since, as per an analysis by PRS Legislative Research.

The financials of the Railways are too complex to be pinned on non-suburban passenger traffic alone and without adequately considering the story of freight movement across NDA and UPA years. But it appears that in prioritising premium trains and upper-class passengers, the Railways are increasingly unwilling to cater to the needs of most Indians.

“The IR has historically been the mode of transport for the aam janta (common people) who have hitherto been the Railway management’s prime focus,” former railway officer Mathew John wrote in The Wire in February 2024.

This trend of sacrificing public services at the altar of commerce predates the NDA. But one of the objectives of the Railways’ 2011-12 “vision statement” was affordable transport, a goal absent from the BJP’s 2024 manifesto.

In the speech of 12 Mar in Ahmedabad mentioned above, Modi promised: “This 10 year’s work is just a trailer. I have a long way to go.”

(Aniket Aga is a researcher and teacher. Courtesy: Article 14.com, a joint effort between lawyers, journalists, and academics that provides intensive research and reportage, data and varied perspectives on issues necessary to safeguard democracy and the rule of law.)