Colombian Uprising Takes Aim at Inequality

Christina Noriega

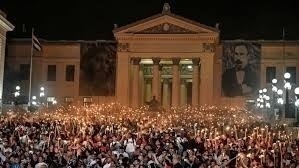

May 18, 2021: On May 12, marches in the Colombian capital of Bogotá that kicked off with a procession of brightly colored balloons ended by nightfall with violent clashes between police and demonstrators. Terror-stricken residents gazed motionless as tear gas and stun grenades, launched by militarized police against protesters, soared outside their homes.

As Colombia enters its third week of unrest, there are no signs that protests will let up soon. What started off as a rebuke of an unpopular tax reform has evolved into a broad-based movement, organized at the granular level by grassroots groups, each with their own demands and grievances. Heavy-handed police repression and fruitless dialogues have exacerbated citizen outrage.

Critics of the tax reform said it intended to close a pandemic-induced fiscal gap at the expense of the poor and middle class. A national strike that started on April 28 successfully pressured President Iván Duque to rescind the proposal. But with their initial goal now met, protests have expanded to include larger demands that reflect a pervasive discontent with President Duque and his governing Democratic Center party, founded by ex-president Álvaro Uribe, who faces strong allegations of paramilitary collusion. Along with escalating the armed conflict with leftist rebels, Uribe implemented neoliberal reforms that opened up the country to multinational extraction of natural resources, privatized national industries, weakened worker protections, and implemented tax policies that benefited elites.

Leading the protests and negotiations is the national strike committee, comprised of Colombia’s biggest trade unions, including the Central Union of Workers and the Colombian Federation of Education Workers. Their ample demands include calls for a universal basic income, free college education, the withdrawal of a health reform bill, the suspension of a forced coca eradication program, support for national industries and economies, an end to racial and gender discrimination, the dissolution of Colombia’s riot control police, and the reversal of a presidential decree that paves the way for hourly wages without benefits.

Many of these demands were initially set forth in a national strike in 2019, when a series of anti-government protests brought tens of thousands of people to the streets. Colombia seemed on the cusp of change then, but the onset of the pandemic stalled negotiations. As talks resume, strike leaders have once again voiced concern over Duque’s reluctance for dialogue.

Dialogue Begins

On the first day of talks on May 10, the strike committee chafed at the Duque administration’s disregard for their demands and for the lives lost during the strike. “There was no empathy with the victims of the violence that has been employed disproportionately against the demonstrators who protest peacefully,” said Francisco Maltés, president of the Central Union of Workers (CUT), in a press conference. “We demand that the massacre end.”

In 15 days of protests, police have reportedly killed 39 people, physically assaulted 362, and sexually abused 16 protesters. Viral videos show police opening fire at crowds of protesters and firing U.S.-made tear gas directly at protesters. Reports that a 17-year-old committed suicide after suffering an alleged case of sexual assault by police officers on May 12 have added fuel to the ongoing outrage at the excessive use of police force.

Negotiations resumed on May 16.

In advance of their meeting, some headway was made on a few demands. The health reform bill that critics said would weaken the public health system in favor of private insurance companies appears to have lost the political backing it needed to pass through Congress. In another victory for the strike, the Duque administration partially ceded on demands for free college tuition. The government announced that poor and middle-class students in public universities and technical schools would be exempt from paying tuition this fall semester.

The strike committee is likely to push further and request permanent free tuition. Meanwhile, other demands, such as a universal basic income, will be harder to agree on. The committee calls for a minimum monthly wage (about $245) for poor Colombians while the pandemic continues to ravage the economy. But detractors believe its cost makes the program unviable.

Last year, the government launched a monthly “income solidarity” payment of about $43 for more than 3 million homes, a plan President Duque proposed to expand and pay for with his tax overhaul. The subsidies fell in line with the president’s conservative posture to restrain public spending.

But for many Colombians, the program has failed to protect them from hunger and poverty. More than 3.5 million Colombians were plunged into poverty in 2020, the unemployment rate soared to 16 percent as of March, and a study from the Andes University describes a 10-year setback in social progress due to the economic fallout of the pandemic.

Colombians like 20-year-old Leidy Torres report cutting back on meals after her and family lost their jobs. “Whereas before we ate meat, now we eat eggs,” said Torres at a peaceful roadblock last week, adding that her family no longer eats three meals a day.

Yet, concessions made so far signal the mounting pressures Duque is facing. The international community, including the United Nations and the European Union, has condemned the police’s excessive and sometimes lethal use of force and urged the administration to meet with strike representatives. More than 50 U.S. Congresspeople are calling for a freeze of sales of U.S.-made crowd control equipment, a suspension of U.S. aid to Colombian National Police, and an end to sales of weapons to Colombia’s riot police until human rights protections are set in place to protect protesters.

Resistance Will Not Be Silenced

The strike committee has requested an investigation into reports of police abuse and the dissolution of the ESMAD riot police, which is allegedly responsible for the majority of the killings. Despite being designed as a non-lethal force, the ESMAD has been accused of 34 killings between its founding in 1999 and 2019. These cases rarely reach a conviction because the ESMAD, along with the rest of Colombia’s police force, sits under the Ministry of Defense and is tried by military courts notorious for impunity.

On top of the demands made by the strike committee, local organizations also insist on being heard. In a recorded video, representatives of Puerto Resistencia, a poverty-stricken Cali neighborhood and one of the epicenters of police violence, requested greater social investment in youth programs, subsidies for students, lower taxes on small businesses, an investigation into the alleged police killings, safety guarantees for protesters, among other demands. “We won’t be excluded, we’re going to be heard,” said a masked protester in a video last week.

At a humanitarian space in the south of Bogotá, where locals have blocked police from accessing a bus station plaza, residents are organizing assemblies to decide on their own list of demands. At a recent assembly, community members gathered in groups to discuss and debate different policy proposals at the national and local level.

“We’re not willing to remain silent about the violence we’ve received historically from the government,” said Laura, a 26-year-old organizer who asked to remain anonymous. “Currently, President Iván Duque and his entire cabinet represent politics of death, politics against life.”

Inequality is a deeply rooted issue in Colombia, where poor farmers armed themselves in 1964 and waged war against state violence and land concentration by powerful elites. The rebel group known as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) laid down its weapons following a peace deal with the government in 2016. But some of the most important points in the deal, which sought to address the underlying causes of the war, remain poorly implemented. The Comptroller’s Office reported it would take 10 additional years to fulfill the main objectives outlined in the deal, including rural investment and a coca substitution program.

For many protesters, a national dialogue is long overdue. But Duque will have to widen negotiations to include various sectors. Otherwise, there is a chance that protests will continue even if a deal is reached with the national strike committee. Grassroots groups that emerged in the 2019 strike are active once again and unwilling to back down on long-standing demands.

“Outcry will continue as long as we don’t receive a convincing response from the government,” said Laura. “The pandemic forced us to stay home and instilled fear in us, but neither the virus nor the lethal force of the police are going to silence us now. Our voices are as loud as ever.”

(Christina Noriega is a journalist based in Bogotá, Colombia. Her work covers human rights, gender equality, the environment, culture, and social movements. Article courtesy: NACLA.)

❈ ❈ ❈

The Roots of Colombia’s Crisis 2021

Andy Higginbottom

There has been a social explosion of the Colombian people against poverty and repression. President Duque’s ‘tax reform’ package was the last straw that broke their patience. The biggest upsurge of sustained popular protest since the 1970s has brought the country to an absolutely pivotal moment: Colombia’s future hangs in the balance.

In this article we look at why Duque sought to impose the tax package and the economic drivers behind it. We also indicate some of the devastating social effects of his rule that have led the people to such deep resistance to what has been falsely presented as a progressive reform.

Introduction

Iván Duque is a mediocre politician that many Colombians comment is little more than a pawn for the former president, ultra-right Álvaro Uribe Vélez, who is still the real ruler of the country. When he came into office in 2018, Duque promised that he would reduce taxes on the corporations. The current package is in fact Duque’s third tax reform.[1] Once COVID-19 hit hard Duque decided not to waste a good crisis and push the neoliberal agenda even more. For the time being the latest proposals have been withdrawn, but the agenda has not.

The social movements at the heart of the National Strike are rightly calling for Duque’s resignation. Even that would not be enough. Duque is the front man for a murderous neoliberal, neo-colonial alliance.

The close alliance that rules Colombia is a mutual dependency between, on the one hand, the country’s own ruling class that is comprised of a cluster of elite economic groups, corrupt politicians, the military and their narco-paramilitary auxiliaries; and, on the other, international big business backed by the U.S. military and the UK. As we will demonstrate, the interests of these groups converge at the expense of the great majority of the Colombian people.

This analysis connecting the internal and the external has major implications for the solidarity we need to deliver.

Sharp Increase in Poverty –A Society in Collapse

The Covid crisis has occasioned a recession in the Colombian economy, a 6.8% drop in production as measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In the midst of the pandemic, there has been a further class polarisation. Moreover, all the indicators show a drop in working class living standards even before Covid hit. The official poverty rate underestimates the real degree of poverty, even so it has leapt up from 36.1% to 42.5% of the population between 2015 and 2020. Increasing poverty is really bad in the cities, where another 10.8% of the population has joined the ranks of the poor. On official figures, 5.7 million more Colombians have been pushed into poverty in just the last three years.[2]

State revenue is being lost to huge profit flows out of the country

The immediate cause of Duque’s reform package is the state’s fiscal deficit. In 2020 Colombia’s tax revenues were only 20 per cent of GDP,[3] whilst state spending was 28% of GDP. The gap between these two amounts, 8% of GDP, was the annual fiscal deficit. Each year of deficit worsens the accumulating indebtedness of the state, which under Duque has shot up from 47% in 2018 to two thirds of GDP in 2021.[4]

Duque’s latest tax reform proposals would both increase taxes and reduce state spending. But there are deep structural problems typical of a neo-colonial country that continually has wealth drained out of it. Not least because a large part of state revenue is being lost to profit flows out of the country in two major ways: firstly, corporate tax breaks for the big companies, whether locally owned or multinational corporations; and secondly, debt repayments to the banks. We will look at these in turn.

The real rate of corporation tax the big corporations actually pay is much less than the official rate of 25% of their profits. Once the various exemption schemes are taken into account, the mining multinationals have only paid around 10% since 2013; and the oil companies even less, around 2% since 2015. What Álvaro Pardo calls a ‘corporate tax giveaway’ of $0.9 billion a year has led to “a real gaping hole that is bleeding the state’s coffers”.[5]

At the height of the commodity boom in 2013 the extractive industries provided a third of government revenues, whilst still keeping spectacular profits. For example, the El Cerrejón coalmine has provided at least U.S. $9.2bn profit for its three owners, the London based Anglo-American and BHP Billiton, and the Swiss multinational Glencore. But the big companies have since slashed their tax payments, and corporation tax is now providing only 8% of government revenues.

On one estimate Colombia loses over U.S. $11.6 billion annually to corporate tax abuse, second in Latin America only to Brazil ($14.6 billion); but much higher on a per capita basis. The lost corporation taxes each year are $232 for every Colombian. To put it another way, the taxes lost are the equivalent of 72% of the state’s entire public health expenditure.[6]

Much of the money not paid in taxes in Colombia finds its way to the U.S. and UK.The City of London plays an unnoticed major role in corporate tax abuse globally. It is at the centre of a spider’s web of offshore tax havens that is “responsible for 28.5 per cent of the $245 billion in tax the world loses to corporate tax abuse every year”.[7]

Then there is a second huge problem, the public debt and the threat of even higher interest rates to pay it off. The extent that the state’s incoming revenues are not available for public use, as they just flow straight out again, is indicated by Colombia’s budget for 2021, designated as follows:

- Operating Expenditure 59%

- Investment 18%

- Public debt and interest payments 23%[8]

Some 23% of all revenues raised goes straight to the banks! The debt payments are U.S. $18.8bn a year. Why doesn’t the government refuse to pay the debt? The reason is that it represents a class interest aligned with the banks, domestic corporations and the multinationals, that would prefer sharing in the exploitation and criminalising of its own people rather than stand up to the beneficiaries of wealth extraction, not to say care anything about the total environmental destruction that is built into the extractivist regime.

International Creditors Turning the Screw One More Time

The international financial institutions pushed for the tax reform which triggered the protests, as revealed by the Bogotá correspondent for the Financial Times (FT) of London:

Colombia’s decade-old status as an investment grade nation will be put to the test as the government of Iván Duque tries to pass a fiscal reform package to steady an economy that has gone haywire during the coronavirus pandemic.[9]

The article explains that ‘steadying the economy’ requires the government to raise taxes and make severe cuts on state spending to close the fiscal deficit if it wants to avoid being charged a higher interest rate on its debts. Unless drastic measures were taken, the credit ratings agencies would downgrade Colombia to near junk bond status,

demoted from a small group of Latin American investment-grade nations that includes Mexico, Chile and Peru.

The FT does not, of course, question the right of credit agencies in Wall Street and the City of London to set terms for the Colombian government, or anywhere else in the world for that matter.[10] Still, its analysis does give insight into the chain of control that links the international centres of financial power at one end with the impossible conditions of life on the streets of Cali, and all of Colombia, at the other.

The tax reform plan was to raise 25.4 trillion pesos (U.S. $6.8 billion) each year from 2022 onwards, of which only 3 trillion pesos (US$0.8 billion) would come from corporations, the rest from taxing the population.[11] Some three fifths of the extra revenues to be raised were pre-allocated to reducing the fiscal deficit, effectively cutting services to pay off the debt, as demanded by the international credit agencies.[12]

Entrenching Inequality

To put the ‘reform’ in the context of existing inequalities, the minimum wage in Colombia is, with transport concessions, just U.S. $269 a month.[13] The distribution of incomes is highly skewed. Libardo Sarmiento notes that “only 12% of employed people in the country earn more than two minimum wages”.[14] The country has one of the most unequal income distributions in the world, with the top 10% taking 50% of all income. The inequality of wealth is even greater. The top 10% own more than 95% of the wealth. Almost all the country’s material wealth is concentrated in the super rich and the super-super-rich.[15]

The reform’s proposed biggest income tax increases of 9% would be for the lower middle class; that is, on incomes of around $1,500 a month. But tax rate increases would only be 2% for the top 10% of earners, those earning around $8,000 a month and above. Working class incomes of up to U.S. $900 a month would attract no increase in income tax. Nonetheless, working class households would be worse off because instead they would be hit by the widening basket of the products falling under VAT at the full rate of 19%, including computers and mobile phones, and such staples as rice and pasta.[16] The poor would only be better off if they stopped eating! Let alone dare they communicate through social media!

Thus, despite Duque naming it ‘social solidarity’, the overall effect of the package would be the opposite, not progressive but regressive; that is greater tax increases for the poor and lower middle class than for the rich. Even without the proposed package, Colombia’s income tax “is extremely lenient on the richest people”. In short, the package would have entrenched inequality, not reduced it.[17]

Militarisation of the State and Country…

The Colombian state is a warfare state, not a welfare state. While state violence has been mostly against its own people, as we are seeing once again today, there is a quid pro quo of mutual support between the Colombian and U.S. military commands that involve Colombia’s international role as a prop for the U.S. (and the UK) imperial strategies.

Ever since the end of the Second World War and the CIA’s assassination of Jorge Eliciér Gaitan, Colombian security forces have maintained close relations with the U.S. military. Colombia sent troops to join the Korean war in the 1950s. The U.S. sent military personnel to Colombia in the early 1960s to stop the spread of the Cuban revolution, and again in a massive way under Plan Colombia in the late 1990s. This inter-state military collaboration is deep seated, institutionalised and continuing. The notorious School of the Americas has trained more Colombian officers than from the rest of Latin America.

Renán Vega points out that the U.S. maintains at least forty bases in Colombia, not the seven usually reported. The bases are of many types, but overall they are set up as forward operating locations from which to launch attacks on Venezuela, or indeed anywhere in South America and the Caribbean.[18] In 2018 Colombia joined NATO, the only Latin American country to do so, in a special status of ‘global partner’.[19]

Despite the country being supposedly in a post-conflict situation, the military is not being cut; on the contrary Duque plans to spend more on them. At U.S. $10.6 billion per annum, Colombia’s military spending is still by far the highest in Latin America as a proportion of state expenditure. There are 267 thousand armed forces, 186 thousand police and 24 thousand civilians on the payroll, nearly half a million personnel in all.[20] Over and above this, Duque wants to spend a further $4.5 billion on 24 new F16 fighter jets from the U.S. corporation Lockheed Martin. The reason given is to have superior air power over Venezuela.[21]

The military machine is turned internally as much as externally. One third of the Colombian army, 82,000 military personnel, are in the ‘mining and energy’ battalions. They are positioned around the mines and oilfields to enforce the security requirements of these extractivist industries, and especially of the UK-based multinational corporations that have predominated in these sectors.[22]

The callousness of the Colombian government and military towards deaths as a result of its operations was highlighted in the Minister of Defence, Diego Molano’s response to an army operation on 2nd March 2021. The army bombed the camp of a dissident FARC group in Calamare, Gauvire department. Initial reports stated that the bombing killed at least 10 people, 4 of whom were minors. Molano’s response was that the young victims had been expendable as they were “machines of war”.[23] A further report by veteran investigative journalist Holman Morris identifies at least 13 children and adolescents, from the age of nine years old upwards, who were either killed or ‘disappeared’ by the army’s airstrike.[24] Even this information has still not evoked any official apology.

Liquidation of the Opposition… Genocide of the Youth, juvenicidio

Supposedly in a post-conflict situation since the signing of the peace agreement between the state and FARC guerrillas in 2016, nothing could be further from the truth. The longstanding presence of ultra right-wing paramilitarism was evermore legitimated and integrated with official state power by Uribe. These links have become even more blatant under Duque. Combined state and ultra-right paramilitary violence has continued unabated in a project to eliminate all forms of opposition, including social and political mobilisation. Since the peace agreement there have been over 1,200 social and environmental activists assassinated, including indigenous people, LGBT activists, women organisers, African Colombians and trade unionists, as well as demobilised FARC guerrillas.[25]

These targets have a clear logic, the targeting and liquidation of people demonstrating their opposition to the dominant system. It is a continuous political genocide,[26] that has now turned a new chapter, the targeting of a whole new political generation: the youth.

The sharp decreases in living standards since 2018, especially in the urban areas, are one of the triggers of the growing revolt. The current system has simply become unacceptable to the millions of Colombian youth condemned to a life with no support and no future.[27] The state has declared war on the youth, determined to crush their rebellion with a fresh political genocide–juvenicidio–targeting working class youth who have thrown themselves onto the front line of the popular resistance, because they have nothing left to lose.[28]

In the two weeks of mass protests from 28th April to 12th May 2021 there have been 39 homicides believed to have been committed by the police state forces, with many other forms of physical violence being reported.[29] The latest reports are of the police mounting a programme of social cleansing against the protestors.[30]

On previous experience, once it senses it has regained the initiative, the Colombian state will be merciless.

UK Responsibility for Repression in Colombia

Police violence in Colombia is both systematic and carried out with complete impunity, internationally as well as nationally. This is one area where the UK’s role is a crucial prop in legitimising Colombian state repression.

It has just been revealed that the UK College of Policing has for the last 3 years been training Colombian police officers.[31] This is the tip of an iceberg of police and military collaboration geared to suppressing popular movements and defending UK multinationals and strategic interests. We cannot expect these strategic commitments to wither away easily, as UK ambitions have become even more imperial post-Brexit.[32]

Lobbying MPs to urge the government stop UK police training and equipping the Colombian police is a start.[33]

We need to go further in this direction and provide full support to all Colombian social movements on the frontline, especially those confronting the social and environmental destruction wrought by UK multinationals.[34] This is a direct link with defending the planet from climate collapse, for which UK fossil fuel companies are especially responsible.[35]

The current crisis points to another area to be opened up, which is to tackle the hidden extraction of Colombia’s wealth by the banks. It’s time to put a stop to the banks robbing the people. We should be joining the dire situation in Colombia with campaigns demanding international debt cancellation.

Colombia is Heading for a Showdown… Take a Stand Here

Each of these three aspects concerning the Colombian state’s fiscal crisis, the non-receipt of corporate taxes, its significant debt payments and the huge continuing military budget all speak to its relations with imperialism.

Duque’s government could refuse to pay the debt and not spend so much on the military, put the money into a proper public health programme; but of course it won’t do that because of the class interest it represents, and if it did so it would risk those very same F16s being turned against it.

A completely new regime that puts the needs of the people before the ruling financial-extractivist-military alliance is needed. The issues are becoming clearer by the day. The country is polarising between the super-rich and the super-exploited poor. Everyone knows it, and people are taking sides. The new ingredient is the emergence of working class youth as political actors, a new generation on the front line of resistance. Once again, Colombia is headed for a showdown.

This is more than an internal matter. The situation calls for urgent international solidarity action that both mobilises to end the human rights violations and, at the same time, tackles the imperialist powers that profit from and so reinforce Colombia’s state violence. We have to break down the very structures that cause the violence.

Because there is an international chain of mutual self-interests based on exploitation and repression, so there needs to be an alternative internationalist chain, a chain of resistance based on solidarity and respect for life.

End Notes

- Libardo Sarmiento Anzola, ‘Reforma tributaria 2021:el tercer raponazo duquista’ Le Monde Diplomatique Edición 210, mayo 2021, pp. 4-7

- Libardo Sarmiento Anzola, La miseria, enfermedad social

- justiciatributaria.co

- Sarmiento, p.4

- razonpublica.com

- actualidad.rt.com

- www.globaltaxjustice.org

- Los beneficios tributarios a las empresas están desangrando al país–Razón Pública (razonpublica.com)

- Gideon Long, ‘ Colombia’s investment grade status at stake in tax battle’ 1st March 2021 Financial Times

- This is part of the general pattern of sharply increasing indebtedness for countries across the ‘Global South’, see John Smith ‘La Mayor Crisis de la Deuda de la Historia ha Llegado’ in Nuestra América XXI: Desafíos y Alternativa s No 50, pp.2-4 at nuestraamericaxxi.files.wordpress.com/2020/12/boletin-50.pdf

- These figures have been calculated at the exchange rate of 3,750 Colombian pesos to 1 U.S. dollar. The convention in Colombia is that a billion pesos is a million million pesos. The convention followed here is that a billion (billion) stands for a thousand million dollars, and a trillion stands for million million. The upshot of these two conversions is that the sum that would be represented in Colombia as 3.75 billion pesos is represented here as 3.75 trillion pesos, and that is equal to U.S. $1.0 billion.

- www.semana.com

- www.salariominimocolombia.net

- Sarmiento, p.5

- La reforma tributaria consolida la inequidad–Razón Pública (razonpublica.com)

- Sarmiento, p.5

- La reforma tributaria consolida la inequidad–Razón Pública (razonpublica.com)

- soaw.org

- www.reuters.com

- www.larepublica.co

- www.infobae.com

- soaw.org

- www.theguardian.com

- www.elespectador.com

- www.indepaz.org.co

- www.cinep.org.co

- www.leftvoice.org

- elturbion.com

- www.indepaz.org.co

- www.contagioradio.com

- www.thecanary.co

- As set out in: www.gov.uk. For critique see: www.peaceinkurdistancampaign.com

- secure.waronwant.org

- www.colombiasolidarity.org.uk and londonminingnetwork.org

- mronline.org

[Andy Higginbottom is an Associate Professor at Kingston University, London where he teaches on slavery and emancipation, the crimes of the powerful, and international political economy. Article courtesy: Colombia Solidarity Campaign, a London-based organisation with members both in the UK and Colombia working in solidarity with oppressed groups and communities affected by foreign (especially U.K.) economic interests which threaten livelihoods, lives and sovereignty in Colombia.]