Madhya Pradesh chief minister Shivraj Chouhan has proposed that every woman stepping out of her home be required to register herself with her local police station so that the police can track her for her safety.

A few days ago, the Chief Justice of India Sharad Arvind Bobde asked why women had been “kept” in the farmers’ protests, and praised advocate A.P. Singh (a man with a record of victim-blaming ‘Nirbhaya’ and boasting of his appetite for ‘honour’ crime) for giving an assurance that women would be sent home and henceforth kept out of the protests.

As an Indian woman, these developments fill me with a sense of foreboding and panic. Shivraj Chouhan and Sharad Arvind Bobde are not, after all, conservative neighbourhood uncles whom I can afford to ignore, humour or attempt to reason with. They are men with immense power, who do not feel obligated to listen to the voices of women. Their whims carry the weight of authority.

I deal with my overwhelming sense of alarm in my usual way – by using words to communicate, as simply as possible to as many people as possible, why these propositions that sound so benign, reek not of care but of control.

We need to tell these powerful and influential gentlemen: women are not a “problem” for which confinement and surveillance are the “solution”. Women are not “things” owned by men, that need to be “protected” from theft or damage.

Women are people with an inalienable right to live the fullest of lives. Everything that prevents their life from being lived to the fullest extent of freedom, is a form of violence.

Violence against autonomy is, by far, the most widespread and the least acknowledged form of gender-based violence in India. Ask me, I have written a whole book documenting and discussing this fact. National Family Health Survey data shows that just 42% of women with no schooling, and 45% of women with schooling, have the right to go “alone to the market, to the health centre, and outside the community”. The India Human Development Survey (IHDS) found that even those women who could go out alone – to workplaces, for instance – are expected to seek permission from some authority figure in the household to do so. Both the NFHS and IHDS surveys found that even Dalit, OBC and Adivasi women experience restrictions on mobility without permission, to more or less the same extent as women from more privileged castes.

In Fearless Freedom, I wrote: “What do these facts and figures really mean? They translate to a life lived ‘crashing against walls’, like a bird caught in a closed room, battered by every attempt to escape and fly free. There’s really no way to dress up this life and romanticise it as ‘safe’. Such intense and obsessive confinement of women is not ‘safety’. It’s time we recognised it as violence in its own right.”

Rape or sexual assault is violence against women’s autonomy – i.e her control over her own body.

Confinement to the home, and surveillance inside and outside the home is also violence against women’s autonomy.

Requiring women to take permission from authority figures in the family to step out of the home is violence against women’s autonomy.

Requiring women to inform the state authorities (like the police) of their movements outside the home is violence against women’s autonomy.

Requiring women to seek permission from the state to convert to another faith or marry someone from a different caste or community is violence against women’s autonomy.

Withholding the right of a woman to take risks (by protesting in cold weather for instance) is violence against women’s autonomy.

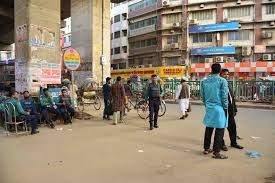

A man is not asked to explain and answer for why he is “outside his house”. The “outside” is accepted as his natural sphere. The very fact that a woman is expected to answer to others for her presence “outside her house” proves that the house is in fact a prison for a very large number of women. As the 2011 book Why Loiter eloquently asserts, women have a right to loiter without purpose, and it is only by asserting and defending this right can women truly have a claim to their city.

Confinement is violence, not safety.

Surveillance is violence, not safety.

Those who prescribe restrictions on women’s freedoms in the name of “safety” are the most likely to voice rape-culture that blames victims, not perpetrators, for sexual violence. Advocate A.P. Singh is a handy example. The honourable CJI thanked Singh for his assurance that women farmers would go home and stay home, away from the protests. (The organisation Singh represented clarified that they had not authorised him to give any such assurance.) Surely you know that the same Singh is the one who declared, in the context of the Delhi 2012 gangrape and murder, “If my daughter was having premarital sex and moving around at night with her boyfriend, I would have burnt her alive. All parents should adopt such an attitude.” The man who justified rape of a woman on the grounds that she went out of her home, at night with her boyfriend, says today that women must stay home, and keep out of protests – and the Chief Justice of India agrees with him! What a disturbing and dangerous meeting of minds!

The Manusmriti, which Shivraj Chouhan, Yogi Adityanath and other BJP leaders revere, declares that women never be free, and must always be in the custody of their father, husband or son. The BJP and RSS act as though it is the Manusmriti that is India’s constitution – and they boast that their views and policies are in line with those of the majority of Indians, while feminist ideas are confined to an isolated, “westernised” minority. A BJP leader Ram Madhav boasted in an op-ed in the Indian Express in 2017 that this liberal, feminist minority which had enjoyed an influence out of proportion to its size, was finally out of the driving seat, and “The mob, humble people of the country, are behind Modi. They are finally at ease with a government that looks and sounds familiar. They are enjoying it.”

In 2019, in another op-ed in the same paper, Ram Madhav called for the “pseudo-secular/liberal cartels that held a disproportionate sway and stranglehold over the intellectual and policy establishment of the country” to be purged from “the country’s academic, cultural and intellectual landscape” under Modi’s second term as prime minister. Contrast this triumphant majoritarianism of the BJP with the “Constitutional morality” that Ambedkar expected the arms of the state to be guided by, even as he recognised that “Constitutional morality is not a natural sentiment… We must realise that our people have yet to learn it. Democracy in India is only a top dressing on an Indian soil which is essentially undemocratic.”

Unlike the RSS and BJP, Ambedkar did not celebrate the fact that democracy sometimes seemed “foreign” to an Indian society riddled with caste-patriarchy; he aimed to challenge and change it. People’s movements in India (trade union, students’, feminist, anti-caste, civil liberties and environmental movements) aim, like Ambedkar, to democratise Indian society – and these movements have been led by masses of ordinary Indian men and women, not by liberal intellectuals. From educators Savitribai Phule and Fatima Sheikh, to anti-dowry campaigners Shahjahan Apa and Satyarani Chaddha, feminist organisers are the products of Indian soil, fighting for a more democratic India!

As we have seen, NFHS data does show that regressive anti-feminist ideas and practices are still widespread in India. But till six years back, women could still appeal to the Courts, at least, and be fairly confident that the outcome would uphold Constitutional morality above social majoritarian morality. Today, we have no basis for such complacence.

With the BJP and RSS controlling government and influencing every institution, women’s legally recognised liberties in India hang by a mere thread. All that stands between women, and regressive laws legalising the shackles on their autonomy, are the courts. And the sheer number of judges in Indian courts who seem to have no understanding or respect for the very concept of women’s autonomy and constitutional morality, does not inspire confidence. It is no coincidence, after all, that some of the inspiring Indian feminist figures of our times (to name a few – advocate Sudha Bharadwaj and teacher Shoma Sen, student activists Natasha Narwal and Devangana Kalita of Pinjra Tod, Ishrat Jahan and Gulfisha who walk in Savitri and Fatima’s footsteps) are in prison today under draconian laws, with no judge who seems to be able to see and end the appalling injustice of their incarceration.

Our rights rest on the chance that the judge who gets to weigh in on such regressive policies and laws will be guided by constitutional morality, and not by his own patriarchal common sense. That is a grim thought.

It is women’s movements, and the extraordinary courage of ordinary women in the face of fascist assaults, that supply the confidence that the courts do not. We draw courage from the young women like Muskan, who told a violent mob that she is an adult and has a right to marry whom she pleases. We draw courage from the young women out to loiter and break the cages of hostels and homes, even as leaders of these movements are thrown in prison. We draw courage from the elderly, grey-haired women who lead movements asserting equal citizenship and farmers’ rights, and refuse to be treated like school kids and “sent home” by paternalistic judges.

The fact is that the followers of the Manusmriti are afraid of the change that women’s movements can bring. And we can smell their fear. And their fear dispels ours.

So Messrs Chouhan, Adityanath and company, the honourable CJI and other honourable judges –

We are not going to be boxed up by you.

We refuse to show you papers to prove our citizenship.

We refuse to register ourselves with the police.

We refuse to allow courts to decide if obnoxious, regressive “laws” and policies are legitimate or not – we will defy them and refuse to obey them no matter what the judges think.

We are going to wash the dirty linen in public – and expose the violence inside our homes.

We need no one’s permission to break our cages.

We are here on the streets – and here we are going to stay.

Get used to it.

(Kavita Krishnan is Secretary, AIPWA and Politburo member of the CPIML. Article courtesy: The Wire.)