Budget 2022–23: What Is in it for the People

Part IV – Budgetary Allocations for Health and Nutrition

1. The Union Health Budget

Terrible State of Public Healthcare in India

The second wave of the corona pandemic was even more devastating than the first wave for India. While India officially reported 4,80,000 deaths from SARS-CoV-2 infections as at the end of 2021, several studies have estimated that the actual death rate was at least six to seven times higher. Most recently, an analysis published in the Science journal on January 7, 2022 found that there were 32 lakh Covid deaths over the period June 2020–July 2021, of which 27 lakh occurred in April–July 2021 (when COVID doubled all-cause mortality). Several other research groups have also put out estimates of India’s pandemic deaths, which range from between 30 to 50 lakh deaths. India could thus account for around a quarter of global pandemic deaths.[1]

India’s ‘godi’ media has simply ignored all these studies that reveal the true extent of the death toll due to the corona pandemic. But it was forced to acknowledge that the country was faced with a serious health crisis, at least during the second wave—when people were desperately searching for oxygen, hospital beds, medical care for their loved ones, and social media was full of these news.

The fact of the matter is, India was facing a health emergency even before the corona pandemic first struck the country in early 2020. Lakhs of people die every year of entirely curable diseases. For instance, TB alone kills more than 3 lakh people every year—that is more than the number of official deaths due to Covid. India is actually known as the disease capital of the world.[2] The reason why these deaths do not make media headlines is that it is the poor who the worst sufferers of this health crisis. But the corona hit everyone, including the rich, and so this crisis could not be brushed under the carpet.

The reason for India’s health crisis—which became so evident to everyone during the second covid wave—is the dismal state of our public health system. And our public health system is in a terrible state, because of deliberate government neglect: India’s public health expenditure is among the lowest in the world. India spends barely 1.5% of its GDP on healthcare (both Centre and states combined). This figure is lower than even most low income countries; the world average is 6%.[3] This was admitted by last year’s Economic Survey (2020-21) too: it stated that India ranked 179 of 189 countries in prioritisation of health in government budgets; and as regards quality and access of healthcare, India ranked 145 out of 180 countries.

Because of low government spending, India’s public health infrastructure is in poor health. To give just one example, in rural areas, the main hospital is called the community health centre (or CHC). It is supposed to have 4 specialist doctors—surgeon, physician, gynecologist/obstetrician and pediatrician. While as per government standards, the country is supposed to have 7800 CHCs, only 5600 exist (that is, 70%). Even more distressing is the admission by government statistics that the working CHCs suffer from a 80% shortage of doctors: they are supposed to have 5600 x 4 = 22400 doctors, but have only 4000! Nearly 4700 CHCs have operating theatres with no surgeons to man them![4]

Including both rural and urban areas, the population–doctor (allopathic doctors only) ratio in India was 11,082:1 in 2017 in government hospitals, 25 times higher than the WHO recommendation of 25 professionals per 10,000 population. Likewise, the average population to government hospital ratio in the country was 55,951, which is also a very high ratio.[5]

With such a massive shortage of doctors, auxillary hospital staff, health infrastructural facilities, no wonder that the pandemic completely overwhelmed our country’s public health system.

Allocation for Healthcare in Budget 2022

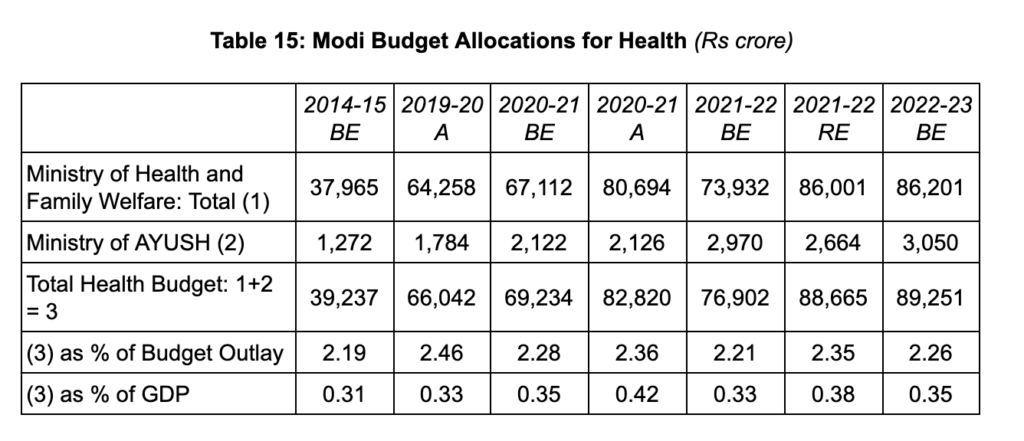

During the first year of the pandemic (2020–21), the Modi Government did increase the total health budget by 25% (2020–21A over 2019–20 A) (see Table 15). While this increase was significant, it was an increase over a very low base, and so, even after this increase, the total health budget of the Centre remained at a lowly 0.42% of GDP. This was less than half of the target set in the National Health Policy 2017 (NHP)—which had promised to increase the Centre’s spending on health to 1% of GDP by 2022.[6] This, when the NHP target is itself very low—it is less than half the global average.

The next year, the second wave of the pandemic made it evident that this increase in health spending was just not enough—our health system simply collapsed before the severity of the wave, leading to lakhs of deaths and bodies floating down the Ganges. Despite this, the Modi Government has refused to increase its health spending. This year’s total outlay on health is just 3.8% more (CAGR) than the actual spending in 2020–21—implying it has reduced in real terms (Table 15).

As a percentage of the total budget outlay, our health budget (2.26%) is less than that for 2019–20 (2.46%), the year before the pandemic, and is barely above the allocation made in the first Modi budget in 2014–15 (2.19%). And as a percentage of GDP, it has fallen to just 0.35% of GDP—way below the target set in NHP-2017 (Table 15).

As a percentage of the total budget outlay, our health budget (2.26%) is less than that for 2019–20 (2.46%), the year before the pandemic, and is barely above the allocation made in the first Modi budget in 2014–15 (2.19%). And as a percentage of GDP, it has fallen to just 0.35% of GDP—way below the target set in NHP-2017 (Table 15).

Such is the Modi Government’s concern about the health of our people even when the world has yet to achieve complete victory over the corona virus. Due to the low levels of vaccination in most underdeveloped countries across the world, the possibility of a new and more dangerous mutant of the virus emerging and spreading across the world remains very high. Therefore, if in India the second wave is now ebbing, this is the right time to increase the spending on our health system and prepare it for the next wave. Instead, the government is cutting its health budget.

Such is the callous attitude of the Modi Government towards tackling the pandemic that it has even cut the vaccination budget of the government—when just 70% people have received at least one dose, 57% of the population is fully vaccinated, and barely 1.4% have received the booster dose [7]. The vaccination budget has been slashed from Rs 35,000 crore in last year’s BE and Rs 39,000 crore in RE to just Rs 5,000 crore this year (allocation for this is not included in the health budget but is included in the budget allocation for the Ministry of Finance – Transfers to States)—implying that the Modi Government is no longer interested in pushing for vaccinating the entire population, forget about giving people a booster dose. This also means that the government policy is now going to be that hereafter the private sector will be the main source of COVID vaccines, meaning that the people will have to pay to get vaccinated. (The hoardings at petrol pumps though continue to laud Modi for the world’s largest free vaccination drive.) Just to remind our readers—the Modi Government was never actually interested in vaccinating the entire population at government expense. It was forced to do so at the prodding of the Supreme Court. The government is quietly returning to its earlier policy.

The government has also cut the budget allocation for the Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR). The ICMR is the the apex body in India for the formulation, coordination and promotion of biomedical research; it led India’s medical response to the pandemic, including development and manufacture of an indigenous vaccine to fight the pandemic. Surprisingly, the Modi Government has cut the allocation for ICMR from Rs 2,358 crore in 2021–22 (BE) to Rs 2,198 crore this year. Taking inflation into account, it is a cut of 15%. It speaks volumes for the seriousness of the government towards the health crisis gripping the country, including preparing for future waves of the pandemic.

National Health Mission

Let us now take a look at the orientation of the government’s limited health budget.

The National Health Mission (NHM)—which comprises National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) and National Urban Health Mission—is one of the most important Central schemes for improving health care for women and children, and ensuring availability of primary health care in rural and urban areas.

A much-hyped component of the NRHM is the Health and Wellness Centres (HWC) scheme, aimed at improving rural infrastructure in health. It was first announced by the then FM Arun Jaitley in his 2018 budget speech. Under the scheme, all the 1.5 lakh health sub-centres in rural areas were to be converted into HWCs, which were to provide comprehensive healthcare, including for non-communicable diseases and maternal and child health services, as well as free essential drugs and diagnostic services. This was a much needed intervention, as the Rural Health Statistics 2017–18 had pointed out that our rural health infrastructure [which is a three-tier structure comprising of health sub-centres at the base, and Primary Health Centres (PHC) and Community Health Centres (CHC) above them], was suffering from an acute shortage of not only medical staff, but even basic facilities like regular water supply and electricity.

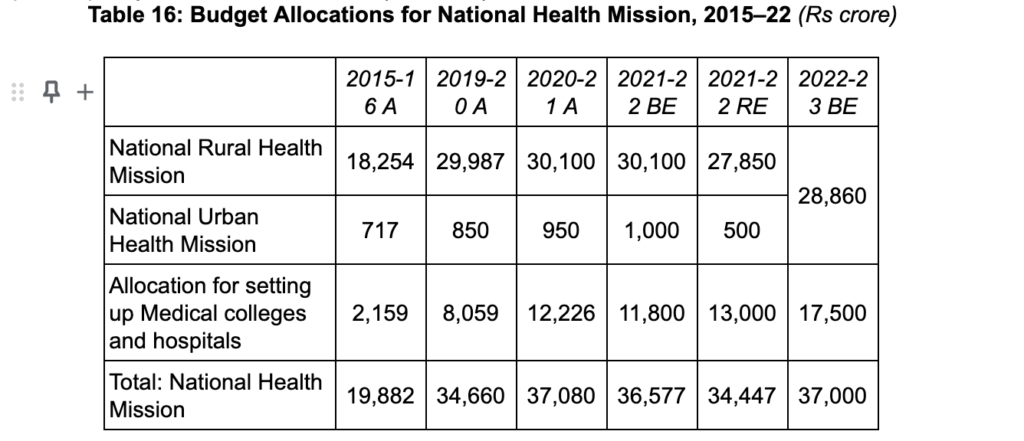

But this scheme has turned out to be a mere ‘Modi health jumla’. The 1.5 lakh HWCs were to be built by this year, 2022, but neither this year’s Economic Survey nor the Union Budget speech mention how many have actually been built. Considering that even after the FM announced this scheme, the budget allocation for NRHM has not seen any significant increase, it is doubtful if a significant number have been built. Over the years from 2015–16 A (two years before the announcement of the HWC scheme) to 2021–22 RE [8], the budget outlay for NRHM has increased at a CAGR of just 7.3% (Table 16)—which is barely enough to keep up with inflation.

This same orientation can be seen in the attitude towards the urban counterpart of the NRHM, the National Urban Health Mission, whose objective is to address healthcare challenges in towns and cities with focus on urban poor. While the Union Cabinet had estimated the share of Central funding for this scheme to be around Rs 3,400 crore per annum way back in 2013 when it approved it,[11] allocation for this has remained much below this amount during the Modi years; last year’s RE show that the government has spent a paltry Rs 500 crore on this (Table 16).

The overall concern of the Modi Government towards strengthening primary healthcare can also be gauged by the share of National Urban + Rural Mission in the budget of the Department of Health and Family Welfare. It was 57% in 2015–16; it has come down to a mere 35% in this year’s budget.

The overall concern of the Modi Government towards strengthening primary healthcare can also be gauged by the share of National Urban + Rural Mission in the budget of the Department of Health and Family Welfare. It was 57% in 2015–16; it has come down to a mere 35% in this year’s budget.

In contrast to this, the budget allocation for building new elite AIIMS like institutes and upgrading government medical colleges (this has been deceptively named Pradhan Mantri Swasthya Suraksha Yojana) and budget allocation for upgrading medical colleges and district hospitals in states (this comes under the National Health Mission) has been sharply hiked in successive Modi budgets, and has gone up from Rs 2,159 crore in 2015–16 A to Rs 17,500 crore in this year’s budget—an increase of 35% (CAGR) (Table 16).

When we examine this increase in the backdrop of the stagnant budgets for Rural and Urban Health Missions, it becomes clear that this is in tune with the overall elitist approach of the Modi Government—build a few high quality facilities amidst a huge expanse of neglect and ruin. This is what is happening in every sector—build a few airports, while neglecting basic transport infrastructure like the public bus transport system; build a few IITs, while neglecting school and college education. This does not mean that airports and IITs are not needed, but if funds are limited, priority should be given to improving the primary transport and education facilities (and actually, as we show in a later article, if the government wants, the funds are also there). Similarly, it is not that new high quality public tertiary hospitals are not needed—the problem is that this is being done while the primary healthcare sector is being neglected. If primary level health services are good—that is, if the HWCs, PHCs and CHCs are running well—most illnesses can be taken care of at this level itself, and this will not only improve the efficiency and reduce the cost of delivery of public health services, it will also improve the overall health status of the people. Therefore, priority should be given to improving primary health care; but in the Modi Government’s concept of the nation, the poor don’t exist.

Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY)

Let us now discuss another much tom-tommed health program of the Modi Government, the Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY). It was first announced in the 2018 budget, and the then FM Jaitley had proclaimed it as “the world’s largest government funded health care programme”. Under this scheme, the government promised to provide medical insurance cover of Rs 5 lakh per family to 10 crore poor families (roughly 50 crore people).

The scheme gives the impression that its aim is to provide universal health care to the poor. But it is not so! It is only a hospitalisation insurance scheme. It does not cover outpatient costs, and these constitute more than two-thirds (68%) of the health related out-of-pocket expenditure (that is, personal spending by people) in India.[9]

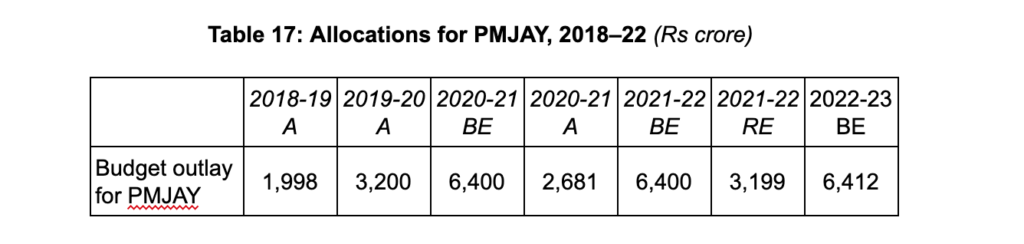

Even as regards hospitalisation coverage—past experience with similar insurance schemes raises legitimate doubts as to what extent will the poor benefit from this scheme. Is the government serious about this scheme? A 15th Finance Commission report estimated that total costs for PMJAY in 2019, taking then levels of hospitalisation rates and expenditure and assuming full coverage, would range between Rs 28,000 crore and Rs 74,000 crore, with projections for 2023 being more than double this range.[10] But actual allocation for this scheme in all the budgets so far has never exceeded Rs 6,400 crore. And actual expenditure under this scheme has never exceeded Rs 3,200 crore! Even during the two corona waves of 2020 and 2021, despite the very large number of hospitalisation cases, actual expense under this head in 2020–21 A was only Rs 2,681 crore and in 2021–22 RE was Rs 3,200 crore (Table 17)! Clearly, this scheme has not really benefited the poor much.

Last year’s Economic Survey raised another important problem with the PMJAY scheme. The Survey said that despite hospitalisation costs being much higher in private hospitals, “quality of treatment does not seem to be markedly better in the private sector when compared to the public sector.”[11]

If private hospitals do not provide better quality healthcare than public hospitals, but are much more costly, and this is a conclusion drawn by the government’s economic advisors, then why is the government pushing for an insurance scheme to treat the poor in private hospitals? Why is it not increasing public health expenditure to improve public hospitals so that people can be treated there at much cheaper rates?

The real purpose behind this scheme is not to benefit the poor, but to transfer public funds to private hospitals. The chief of the Ayushman Bharat scheme tweeted some time ago that private hospitals should quickly get themselves empanelled with the scheme as, “We are offering you business of 50 crore people!”[12]

Actually, the PMJAY is an important component of the Modi Government agenda to privatise health care in the country!

As a part of this, the Centre has already announced incentives for the private sector to set up hospitals in Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities, to the extent of providing them grants (not a loan!) of up to 40% of the total cost of the project! As if this was not enough, the Niti Aayog and the health ministry have also recommended to all states that they partially privatise their district hospitals.[13]

But this would only increase out-of-pocket expenditure of patients, as most diseases do not require hospitalisation! The poor would be the worst sufferers. The health crisis gripping the country is only going to worsen.

So, in name of “world’s largest healthcare initiative”, the Modi Government is destroying whatever little that remains of India’s failing public healthcare system, and privatise it.

2. Budget and Nutrition Schemes

Hunger and Malnutrition ‘Emergency’

As discussed in Part I of this budget series, India is facing a hunger and malnutrition crisis. The Global Hunger Index (GHI) is a multidimensional statistical tool designed to comprehensively measure and track hunger globally and by country and region. It considers four indicators to compute the score of countries—share of the population that is undernourished, share of children under five who are wasted (low weight for height), share of children under five who are stunted (low height for age), and under-five mortality. On this basis, in its latest rankings for 2021, it ranked India a very low 101 out of 116 countries for which sufficient data was available to calculate the GHI scores. It placed India in the ‘serious’ hunger category. India’s rank has been on the downward trend for the last five years, since 2016.[14]

India is also at the epicentre of a global stunting crisis, due to child malnutrition. Data from the National Family Health Survey–5 (2019–20) are now available. They show that 67% children suffer from anaemia, an indicator of nutritional deficiency. The indicators of severe malnutrition among children are also very bad: 36% of children under the age of five are stunted (low height for age, indicating chronic or long-term malnutrition), 19% are wasted (indicating acute malnutrition), and 32% are underweight (low weight for age, indicating both chronic and acute malnutrition).[15] The survey was conducted before the pandemic struck. The pandemic has led to a huge increase in unemployment, fall in incomes, and crores of people being pushed below the poverty line; consequently, all these malnutrition indicators must have considerably worsened.

Under /mal-nutrition severely stunts intellectual, emotional and physical growth. Studies also show that the effect of malnutrition is most acute in the age group from 0 to 3 and this cannot be mitigated in one’s adult life; in other words, both body growth and brain development are permanently adversely affected.

Clearly, for a country facing such a hunger and malnutrition crisis, this should be the Most Important crisis facing its policy planners, and they need to urgently address it.

Unfortunately, the Economic Survey makes no mention of this crisis, even though the NFHS-5 is an official survey. And the budget speech of the FM does not even mention the words ‘hunger’ and ‘malnutrition’—for our country’s policy makers living in their ivory towers, our country is on its way to becoming an economic superpower, these problems don’t exist.

Let us see how the various schemes meant to address the nutrition requirements of the people have fared in this latest budget of the Modi Government.

Food Subsidy

This is the most important programme in the country to tackle this hunger and malnutrition crisis. Under this, the government provides essential rations to the poor at subsidised rates through the public distribution system (PDS). This food subsidy programme is mandated under the National Food Security Act (NFSA), passed by the Parliament in 2013.

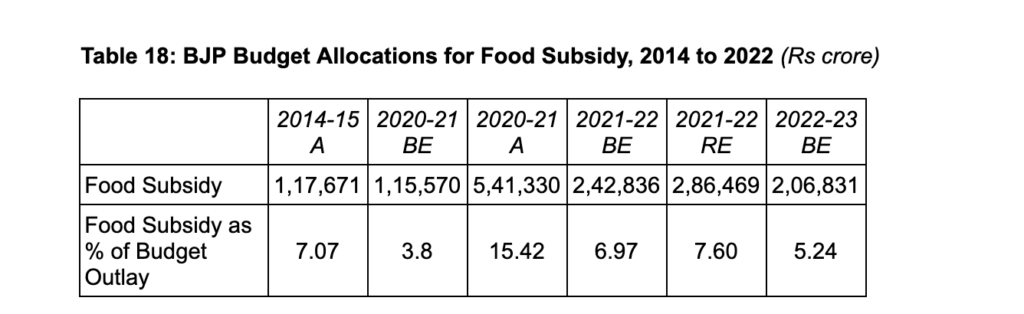

The Modi Government is the most anti-people government to have come to power at the Centre. Till before the pandemic struck in 2020, the food subsidy both as a percentage of budget outlay and as a percentage of GDP had continuously fallen in the seven budgets presented till then (2014–15 A to 2020–21 BE)—the decline had been so steep that allocation under this head as a percentage of budget outlay had fallen by half over these seven budgets (see Table 18)! This was despite the fact that our godowns were overflowing with foodgrains, so much so that our country had become the world’s biggest rice exporter,[16] while even official figures admitted that one-fourth of our population was living below the already very low poverty line.

Then, during the first year of the pandemic (2020), due to the widespread distress caused by its callous handling of the pandemic, including the abrupt lockdown and an extremely inadequate relief package, the government was forced to increase its food subsidy budget and provide free rations to the people. The budget papers reveal that the government’s food subsidy budget (2020–21 A) increased by more than 4 times, to Rs 5.41 lakh crore, as compared to the budgeted Rs 1.16 lakh crore (Table 18).

Since then, despite the killer second wave in 2021, the government has been claiming that the economy is fast returning to normal—even though the GDP figues belie this claim, as we have explained in Part I of this budget series. And so, it has once again started cutting its food subsidy budget. It reduced it by nearly half in last year’s revised estimates (Rs 2.86 lakh crore). This year, it has further slashed the food subsidy by a huge 27% as compared to last year’s RE (to Rs 2.07 lakh crore). While this figure for 2021 BE looks much larger than the 2020 BE, as Table 18 shows, the amount as a percentage of budget outlay is actually less than for 2014 Actuals.

Since then, despite the killer second wave in 2021, the government has been claiming that the economy is fast returning to normal—even though the GDP figues belie this claim, as we have explained in Part I of this budget series. And so, it has once again started cutting its food subsidy budget. It reduced it by nearly half in last year’s revised estimates (Rs 2.86 lakh crore). This year, it has further slashed the food subsidy by a huge 27% as compared to last year’s RE (to Rs 2.07 lakh crore). While this figure for 2021 BE looks much larger than the 2020 BE, as Table 18 shows, the amount as a percentage of budget outlay is actually less than for 2014 Actuals.

In the medium term, the government is planning to end procurement of foodgrains and eliminate the public distribution system, and replace it by cash transfers to the poor, which can then be suitably wound down to reduce the food subsidy bill even more (just like has happened for cooking gas). That was one of the aims of the three farm bills that the farmers so resolutely fought against, forcing the government to withdraw the bills. Considering the anti-poor anti-farmer nature of the Modi Government, it should soon come up with a new trick to further reduce its food subsidy bill.

Other Nutrition Schemes

The previous governments had put in place several “nutrition” schemes oriented towards pregnant women and children. While the funding for them was inadequate, at least they attempted to address the problem. The most important of these schemes are:

- Anganwadi Services: This is probably the most important of these nutrition schemes. It is a programme aimed at providing health, education and supplementary nutrition to mothers and children below 6 years of age.

- Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana: This programme was mandated by the NFSA, passed just before the 2014 elections. Under this, an allowance of Rs 6,000 is to be given to all pregnant and lactating mothers, to partially compensate them for wage-loss so that the woman can take adequate rest before and after delivery.

- Apart from these three, there are several other smaller schemes too.

The Modi Government has been gradually cutting its allocations for all these schemes ever since it came to power in 2014. Thus, during its first seven budgets, that is, till 2020:

- Allocation for Anganwadi services were cut in real terms by one-third.[17] This huge reduction has been made, despite a damning Niti Ayog Report of 2015 showing that around 41% of the Anganwadis have inadequate space, 71% are not visited by doctors, 31% have no nutritional supplementation for malnourished children and 52% have bad hygienic conditions.[18] The reduction in budgetary allocations since then only means that the conditions must have only got worse.

- The Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana was given approval by the Parliament in 2014. But after coming to power in 2014, the BJP delayed implementation of this programme for 3 years. Intense pressure from activists finally forced the FM to announce the implementation of this scheme in his 2017 budget speech. It is a very insensitive government that is in power. To reduce the budget allocation for this scheme, the FM attached several conditionalities, which have resulted in exclusion of more than 50% of the country’s women from this scheme. With the result that the FM has been allocating only around Rs 2,500 for this scheme, whereas a genuine allocation for this scheme would require an allocation by the Centre of at least Rs 9,700 crore per year (assuming Centre–State sharing to be in the ratio of 60:40).[19]

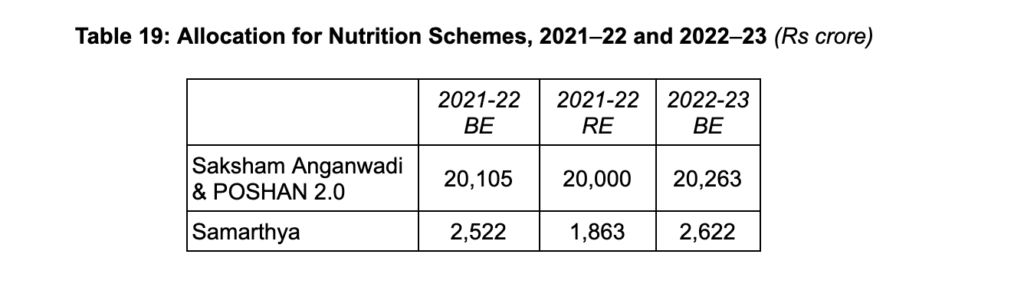

Then, last year, the Modi Government resorted to its typical smoke-and-mirrors routine to fudge the allocations for these schemes by clubbing them together. Four schemes—Anganwadi Services, Poshan Abhiyan, Scheme for Adolescent Girls, and National Crèche scheme—were clubbed together and renamed as Saksham Anganwadi & POSHAN 2.0; while the Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY) was merged with some women empowerment schemes under a new head Samarthya. As we showed in our budget analysis article last year, comparing like with like, there was a decline in allocation for both these combined heads as compared to the 2020–21 BE. The allocation for Saksham Anganwadi & POSHAN 2.0 was less than the combined allocation for its constituent schemes in the previous year by 18%; while the allocation for Samarthya was less by 7%.[20]

In Union Budget 2022–23, the National Crèche Scheme has been taken off from Saksham Anganwadi & POSHAN 2.0, and merged with schemes under Samarthya. Even after that, the allocation for Saksham Anganwadi & POSHAN 2.0 (2022–23 BE) is more than the allocation for the previous year (2021–22 BE) by just 0.8%—implying a considerable cut in real terms (Table 19).

So far as Samarthya is concerned, some schemes from this have been removed and brought under another umbrella scheme called Sambal. Since the disaggregated allocations are not available, it is not possible to compare the allocation for Samarthya for this year with that for the previous year.

So far as Samarthya is concerned, some schemes from this have been removed and brought under another umbrella scheme called Sambal. Since the disaggregated allocations are not available, it is not possible to compare the allocation for Samarthya for this year with that for the previous year.

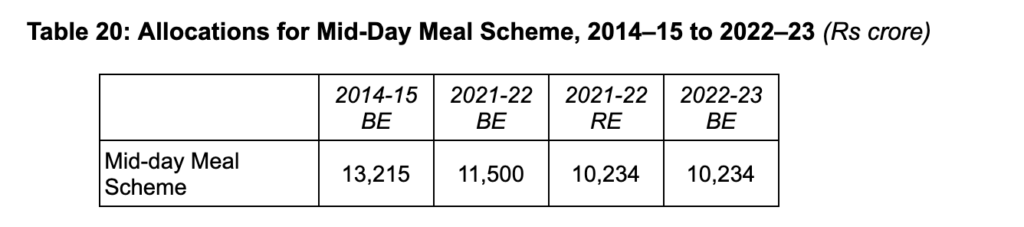

Mid-day Meal Scheme

This is another important nutrition programme to combat the huge malnutrition levels among children in the country; an additional objective is to improve school enrolment and child attendance in schools. Allocation for this comes under the Ministry of Education. But the government is not willing to allocate a decent amount for providing one nutritious meal a day to our children, despite the fact that more than one-third of the country’s children under five—about 4.7 crore souls—suffer from stunting. The allocation for this year is not only less than the allocation made in last year’s budget estimate, it is also less than the budgeted allocation for this scheme in the Modi Government’s first budget (2014–15) (see Table 20). Which means that the allocation for this important child nutrition scheme has been cut by nearly 60% (CAGR, assuming inflation of 8% per year) over the nine Modi budgets (2014–15 to 2022–23).

PM Modi is more of a showman than a Prime Minister. Even while making this huge budget cut, a shameless FM has re-named the Mid-day Meal scheme as Pradhan Mantri Poshan Shakti Nirman (PM POSHAN).

Total: Nutrition Schemes

Adding up the allocation for all the nutrition schemes (excluding food subsidy), while the schemes are many, the total allocation is just (20,263 + 2,622 + 10,234 =) Rs 33,119 crore. This is just 0.84% of the total Union Budget outlay.

3. Budget and Pensions

More than 90% of the people in India work in the informal sector. These workers do very hard, back-breaking work, and so by the time they become old, their bodies are broken and they suffer from many diseases. Therefore, apart from providing them universal and free health care facilities—not just hospitalisation but free outpatient facilities too—it is essential that the government provides them a decent old age pension too.

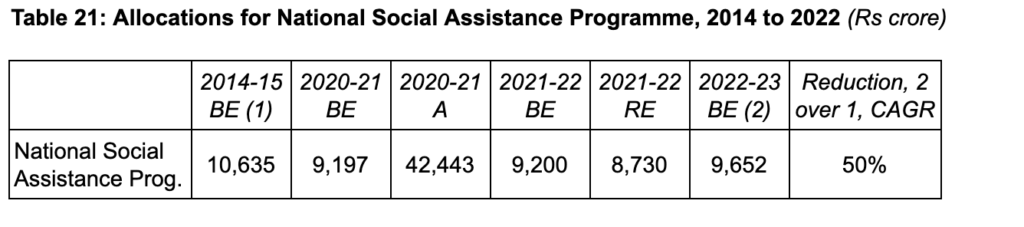

Presently, the main programme for providing social security to the poor and especially those working in the unorganised sector is the National Social Assistance Programme (NSAP). Within this umbrella programme, there are several schemes—to provide pensions to the poor in old age, pensions to the widows and the disabled, and also a National Family Benefit Scheme to provide a lump sum payment to poor households on the death of their primary breadwinner.

The Modi Government has stopped releasing official data about poverty. According to one estimate, as given in Part I of this budget series, the total number of poor in country increased during the Modi years and reached 34.6 crore in 2019–20. Another estimate made by economists Amit Basole and Rosa Abraham of the Centre for Sustainable Employment (CSE), Azim Premji University put the number of poor at 29.9 crore. They base their estimate on the national minimum wage suggested by the official Anoop Satpathy committee.[21]

Despite these huge and worsening poverty levels, the Modi Government during the first seven years of its rule kept the budgetary allocation for the NSAP at the scandalously low level of less than Rs 10,000 crore per year! It even reduced it over the years (see Table 21)!

Then the pandemic struck, and the Modi Government’s callous handling of it pushed several crore more people below the poverty line. According to the study by the CSE economists cited above, during the first eight months of the pandemic (March to October 2020), an additional 23 people fell below the minimum wage threshold poverty line. The Modi Government initially sought to ride out the pandemic with empty slogans. Subsequently, it did release a very inadequate relief package, which again was accompanied by a lot of bluster. One of the components of this package was a direct transfer of Rs 1,500 to all women account holders of Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (a total of 20 crore women). Consequently the revised estimates for 2020–21 show a jump in the total allocation for NSAP to Rs 42,617 crore (Table 21).

The next year (2021), the country was struck by an even bigger killer pandemic wave, which wrought havoc across the country. As the wave receded, some economic recovery took place, but as we have discussed in Part I of this budget series, the condition of the poor has not recovered to even the 2019–20 level. This is also borne out by an Oxfam report released in January this year that estimates that 84 per cent of households in the country suffered a decline in their income in 2021 (see Part I of this budget series).

Despite these heartbreaking figures, a cold-hearted government has drastically reduced its allocation for the NSAP—the main programme in the country to provide social assistance to the poorest sections of society. In fact, it had slashed this allocation in the last year’s budget estimates itself—to an abysmally low Rs 9,200 crore. Even this was not fully spent during the year, the revised estimates put this figure at Rs 8,730 crore. This year, the allocation has been marginally increased to Rs 9,652 crore. It continues to remain below the allocation made in the first Modi budget of 2014–15 (Rs 10,635 crore)—which implies a reduction by more than 50% in real terms (CAGR, assuming inflation of 8% per year).

Even if we assume that the total number of poor to be around 40 crore, the annual allocation of Rs 9,652 crore for them under the NSAP works out to a social assistance of Rs 240 per person per year—a princely sum indeed!

Notes

1. Ditsa Bhattacharya, “India’s COVID-19 Deaths 6–7 Times Higher Than Official Figures: Analysis”, 10 January 2022, https://www.newsclick.in; Murad Banaji and Aashish Gupta, “With COVID-19, India Experienced Its Greatest Mortality Crisis Since Independence”, 5 October 2021, https://science.thewire.in.

2. See: Neeraj Jain, “Modinomics = Corporatonomics: Part IV: Modi’s Budgets and the Social Sectors: Health”, Janata Weekly,

3. “India’s Health Burden”, Down to Earth, https://www.downtoearth.org.in; “India Needs to Reform its Ailing Healthcare”, December 18, 2017, https://www.asianage.com; “R 3: Amount India Spends Every Day on Each Indian’s Health”, June 21, 2018, https://www.indiaspend.com; “Who Is Paying for India’s Healthcare?”, April 14, 2018, https://thewire.in.

4. Figures from Rural Health Statistics, 2017—18, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt of India: “RHS2018 – nrhm-mis.nic.in”, https://nrhm-mis.nic.in.

5. “Why India’s Public Health Facilities May Suffer Despite a Likely Rise in Health Spending”, January 28, 2019, https://www.indiaspend.com.

6. “BJP 2014 Manifesto Check: How has the Modi Government Performed on its Healthcare Promises?”, March 31, 2019, https://scroll.in.

7. “Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations”, https://ourworldindata.org, accessed on February 28, 2022.

8. We are comparing with last year’s RE and not with this year’s BE as this year’s budget figures do not give the budget outlay for NRHM separately, the budget outlays for NRHM and NUHM have been merged.

9. “Indians Sixth Biggest Private Spenders on Health Among Low-Middle Income Nations”, May 8, 2017, https://archive.indiaspend.com; “Evolution and Patterns of Global Health Financing 1995–2014”, April 19, 2017, https://www.thelancet.com.

10. Soham D. Bhaduri, “A Health Scheme Sans Clout”, March 10, 2020, https://www.thehindu.com.

11. Economic Survey 2020–21, Vol. 1, p. 163.

12. “Budget 2019: Ayushman Bharat Gets Rs 6,400 Crore, But to Benefit Private Sector”, February 1, 2019, https://thewire.in.

13. “In the Wake of Ayushman Bharat Come Sops for Private Hospitals”, January 9, 2019, https://thewire.in; “Only a Strong Public Health Sector Can Ensure Fair Prices and Quality Care at Private Hospitals”, March 28, 2019, https://scroll.in; Shailender Kumar Hooda, “With Inadequate Health Infrastructure, Can Ayushman Bharat Really Work?”, November 26, 2018, https://thewire.in.

14. “Data: Where Does India Stand on the Global Hunger Index?”, 23 October 2021, https://www.thehindu.com.

15. Payal Seth and Palakh Jain, “What NFHS-5 Tells Us About the Status of Child Nutrition in India”, 26 November 2021, https://thewire.in.

16. For more on this, see our booklet: Is the Government Really Poor, Lokayat publication, Pune, 2018, http://lokayat.org.in.

17. Neeraj Jain, “Budget 2021-22: What Is in it for the Poor? – Part 4”, Janata Weekly, 4 March 2021, https://janataweekly.org.

18. Sourindra Mohan Ghosh, Imrana Qadeer, “An Inadequate and Misdirected Health Budget”, 8 February 2017, https://thewire.in.

19. Dipa Sinha, “Budget 2017 Disappoints, Maternity Benefit Programme Underfunded, Excludes Those Who Need It the Most”, 3 February 2017, http://everylifecounts.ndtv.com.

20. Neeraj Jain, “Budget 2021-22: What Is in it for the Poor? – Part 4”, op. cit.

21. Shreehari Paliath, “Second COVID Wave to Hit Jobs, Economy Harder”, 19 May, 2021, https://www.indiaspend.com.

(The author is an activist with Lokayat, Pune and the Associate Editor of Janata Weekly.)