Budget 2022–23: What Is in it for the People

Part II – The Budget and the Agricultural Sector

This year, the part of the budget speech devoted to agriculture is important for two reasons.

One, this is the year 2022, the target year the PM himself had set way back in 2016 for doubling farmers’ income. Since then, he has repeated this promise several times. The then FM Arun Jaitley had also mentioned this in his budget speech for 2016, and it has been a staple item in all subsequent budget speeches.

But as we have discussed in our previous budget speeches, this promise was a mere jumla, the FM was never serious about it, and so, predictably, this year’s budget speech makes no mention of this promise. Instead, a new goal post has been set up for 25 years hence—the FM has made several new promises for this 25-year ‘Amrit Kaal’.

In our budget analysis, let us at least see what has happened to farmers’ income during the Modi years.

As per the government’s Doubling Farmers’ Income Committee report, the benchmark household income of 2015–16 was Rs 8,059 per month and this was promised to be doubled in real terms. Taking inflation into account, the target income by 2022 is supposed to be Rs 21,146 per month. Three years later, the estimated monthly income of farm households in 2018–19 was Rs 10,218 per month in nominal terms, as shown by NSSO 77th Round data released in 2021. Taking into consideration the subsequent annual growth rates, and assuming that the farmers’ income has increased by the same amount, the farmers’ income would have only reached Rs 12,445 per month in 2022. The target of Rs 21,146 remains a mirage (see Chart 2).[1]

Chart 2: Actual and Projected Agricultural Income Growth (Rs / month)

Not only has the government failed to increase farmers’ income, on the contrary, farm distress has been worsening.

According to recent NSO survey conducted in 2019 and released on September 10, 2021, more than half of India’s agricultural households (50.2%) were in debt, with an average outstanding debt of Rs 74,121. The average debt had gone up considerably since the previous survey in 2013—by a huge 58%. The average annual income of agricultural households was Rs 1.23 lakh. This means that the average debt was 60% of the average income.[2] Since these are average figures, this obviously means that a very large number of farmers must be facing a serious debt crisis. No wonder that the 2021 report of the National Crime Records Bureau found that farmer suicides increased in 2020, as compared to 2019. There was also a massive increase of 18% in suicides among agricultural labour.[3]

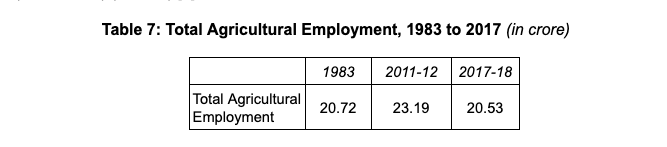

The result of this worsening agrarian crisis is that employment generation in agriculture has suffered an absolute collapse. Total agricultural employment in 2011–12 was 23.19 crore; it fell to 20.53 crore in 2017–18. The Modi years have proven to be so disastrous for agriculture that total employment in agriculture has fallen to even below the 1983 level (20.72 crore) (Table 7).[4]

The FM of course did not mention any of this in her budget. She repeats the PM’s jumla in his independence day address—that we have entered Amrit Kaal, a 25-year path of long term growth.

The second reason why this year’s agricultural component of the budget speech is important, is because it comes in the backdrop of a 16-month long farmers agitation, which finally forced the PM to withdraw the three farm laws. It is a very important defeat for the agenda the Modi Government has been pursuing for the past eight years it has been in power—to hand over control of Indian agriculture to big corporate houses. However, neither the Economic Survey, nor the FM’s budget speech, make any mention of the enactment of three farm laws, the farmers’ struggle, and repeal of the laws by the Parliament.

That is not surprising. It is a fascist government that is in power at the Centre. It tried every trick in the book to defeat the agitation, but the farmers’ peaceful and dignified protest ultimately forced it to retreat. Fascists do not like defeats, they are going to relaunch their offensive sooner or later.

All this was about what should have been in the budget, but is missing. Let us now analyse what is there in the FM’s budget speech as related to agriculture.

In her budget speech, the FM began the section on agriculture by proudly declaring that in the present year 2021–22, 1.63 crore farmers will benefit from government procurement of paddy and wheat. What she does not mention is that last year, 1.97 crore farmers were supposed to have benefited, that is, 34 lakh more (This figure is from her 2021 budget speech). More importantly, she is silent on the two most important demands of farmers. One—that the government implement the recommendation of the Swaminathan Commission that farmers be given MSP which is 50% over the C2 cost of production (which is the comprehensive cost of production). And two—that the government evolve a mechanism to ensure that farmers actually get minimum support price (MSP) for their crops. Two months ago, while repealing the three farm laws after a year long agitation by the farmers, the government had promised that it would set up a committee for this—but it has not so far initiated any action on this.

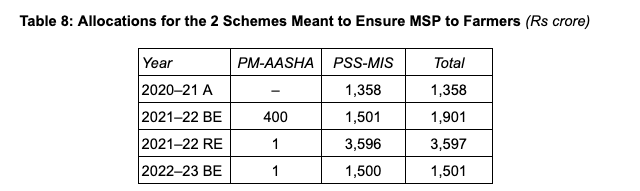

How far the government is serious about ensuring that farmers get a profitable price for their produce can be seen from the fact that the government has sharply cut its allocation for the two schemes meant to assure MSP to farmers—the Pradhan Mantri Annadata Aay Sanrakshan Abhiyan (PM-AASHA) and the Price Support Scheme-Market Intervention Scheme (PSS-MIS)—by more than 50%. Last year, probably in responses to the farmers’ agitation, the RE showed a considerable increase as compared to the BE (see Table 8).

The other scheme that guarantees farmers a decent price for their produce is government procurement for implementing the National Food Security Act (NFSA)—but as we see in a later article, the government has slashed this budget too by a whopping 28% over last year’s RE.

More disconcertingly, the Budget speech seeks to promote drones on a large scale for spraying pesticides and chemicals. The budget also talks about use of drones for promoting digitisation of land records. This is another important reform that is being promoted by the World Bank and pro-corporate economists. They have called upon India to allow acquisition of agricultural land by investors. For this, it is first necessary that the Indian government digitise existing land records as land titles in India are unclear—once this is done, then a highly efficient land market can come into existence in the country, enabling agribusiness corporations to gradually acquire agricultural lands from farmers. This innocuous sounding reform is therefore an important step to promote corporatisation of agriculture.[5]

This year’s agricultural budget does contain reference to several grandiose schemes announced for sustainable and integrated development of agriculture in the previous budgets. These include schemes such as Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (PKVY), Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchai Yojana–Per Drop More Crop (PMKSY–PDMC), National Project on Organic Farming, National Project on Soil and Health Fertility, Rainfed Area Development and Climate Change (RAD and CC), and so many others. This year, all of them have been subsumed under the PKVY. But the seriousness of the FM towards organic farming / sustainable agriculture can be judged from the financial allocation made by her for their implementation. The budget papers reveal that total budgetary allocation for the revamped PKVY, the umbrella programme, is a mere Rs 10,433 crore; this amount is only marginally higher than the total budget outlay these schemes in last year (2021–22) budget estimate. In real terms, the budget allocation has fallen. Further, the revised estimates for last year reveal that the government spent only 50% of the allocated amount.

Total Budget for Agriculture Related Ministries

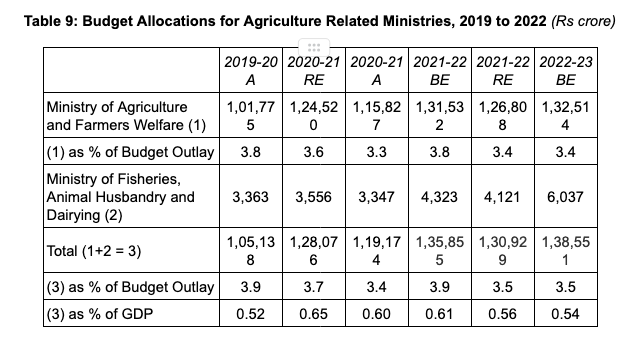

The budget statistic that best reveals the overall orientation of our FM and PM towards agriculture is the total allocation for the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare. As we have discussed in our Budget talk last year, during the pandemic year 2020–21, the relief package provided for agriculture was actually negative—that is, the 2020–21 RE as compared to the BE had actually fallen by a huge 12.8%. It now turns out from this year’s budget papers that actual expenditure was even lesser than the RE for that year. The allocation for agriculture was marginally hiked in last year’s budget estimate, but the revised estimate again shows a fall. This year, the allocation has been raised by 4.5% over last year’s RE, implying a cut in real terms (Table 9).

An important sector that can help provide some relief from the agrarian crisis is the livestock sub-sector (includes sectors like dairy, poultry and meat) and fisheries sub-sector. The livestock sector provides additional income to a large section of small and marginal farmers; while it is estimated that fishing, aquaculture and allied activities provide livelihood to more than 1.4 crore people. But budget allocation for this Ministry is minuscule—barely 0.1% of the total budget outlay (Table 9).

Adding up both these allocations, total Modi Government budget allocation for the Ministry of Agriculture and the related Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairying works out to a mere 3.5% of the total budget outlay—for a sector that provides livelihoods to more than 50% of our population! As a percentage of GDP, it is a tiny 0.54% (Table 9).

Budget for Rural Development

Another important budget allocation that intimately affects agriculture is public spending on rural development.

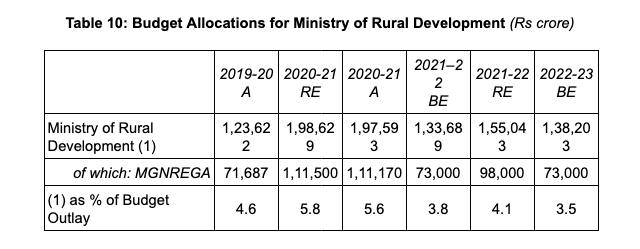

If we leave out the enhanced allocation for pandemic year 2020–21, when the government was forced to hike its allocation for MoRD because of a huge spike in rural distress because of which it was forced to increase its allocation for the rural employment guarantee scheme MGNREGA, the budget papers show that budget allocation for this ministry has consistently fallen over past few years—it was 4.9% of the budget outlay in 2018–19 A, 4.6% in 2019–20 A, 4.1% in last year’s RE, to just 3.5% in this year’s BE (Table 10).

MGNREGA

The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGA) is the most important scheme under the Department of Rural Development. It is a demand based scheme that guarantees a minimum of 100 days of employment in a year to every willing household. Significantly, it guarantees time bound employment, within 15 days of making such a requisition, failing which it promises an unemployment allowance.

This scheme has practically been a lifeline for the rural poor, providing them at least some minimum employment in a situation when unemployment and poverty have reached their worst levels in several decades.

Therefore, it is not a surprise that demand for work under this scheme reached its highest ever level during the pandemic year 2020–21, when crores of people had been forced to return to their villages due to the lockdown. The Modi Government—which has been seeking to undermine this scheme ever since it came to power in 2014—was forced to increase its allocation for this scheme from budgeted Rs 61,500 crore to Rs 1,11,170 crore (as seen in the Actuals) (see Table 10). Around 13.32 crore people applied for work under the scheme, out of whom 13.29 crore were given work.[6]

Even this increase was not enough to meet the increased demand for work. Lakhs of people who applied for work under this scheme were unable to get work, due to lack of funds.[7] For those who did manage to get employment under this scheme, the government admits that instead of 100 days work, an average of 51.52 days of work was provided under the scheme in 2020–21.[8] Whereas, given the severity of the crisis, many states requested the government to provide at least 200 days of work to each needy household.[9] The wage rates for this scheme also need to be raised, as they are significantly lower than the legally prescribed agricultural minimum wages in several states.[10] This means that the government needed to at least double its allocation for this scheme from Rs 1.11 lakh crore to more than Rs 2 lakh crore—which of course it refused to do.

Despite the continuing economic crisis and demand for work even after the lockdown was lifted, the FM cut the budget allocation for MGNREGA in the 2021–22 BE by one-third as compared to the 2020–21 RE. The allocation got exhausted by the middle of the year, and the Centre was forced to increase the budget allocation for this scheme from the budgeted Rs 73,000 crore to Rs 98,000 crore.

Demand for work under this scheme has continued to remain at very high levels. In 2021–22, till the first week of January, 11.30 crore people had applied for work, of which 11.22 crore were given work.[11] A statement by the NREGA Sangharsh Morcha released just before this year’s budget demanded that the government allocate at least Rs 3.62 lakh crore for NREGA—only then will the government be able to provide the mandated 100 days of employment to all the needy households, at an average wage rate of Rs 269 per day (calculated from the minimum agricultural wages announced by various state governments), after paying the last year’s dues.[12]

And yet, in the budget estimates for this year, the government has once again reduced the outlay for this scheme by 25% as compared to last year’s RE; allocation for the scheme remains the same as last year’s BE, at Rs 73,000 crore (Table 10).

What’s more, there are pending liabilities under the scheme to the tune of Rs 18,350. This means that the effective allocation for this year is only Rs (73,000 – 18,350 =) 54,650 crore. The NREGA Sangharsh Morcha has estimated that this allocation is enough to provide employment to all job card holders (nearly 10 crore) for only 16 days![13]

Reduction in Fertiliser Subsidy

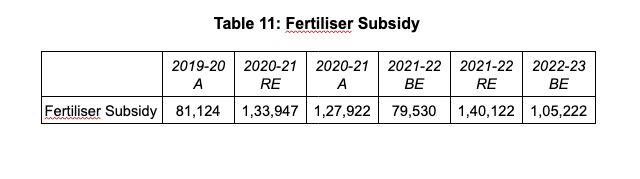

Another important support provided by the Central Government to agriculture is in the form of subsidy on market price of fertilisers, so as to keep the price of this important agricultural input in check. In 2021, IFFCO, the country’s largest fertiliser manufacturer, increased prices of fertiliser by 48–58%. India is also a big importer of fertilisers as successive governments have neglected taking steps to increase domestic production. Consequently, India imports a third of its fertiliser consumption, and global fertiliser prices have also gone up. During the current year (2021–22), to keep fertiliser prices in check, the government was forced to hike its fertiliser subsidy from the budgeted Rs 80,000 crore to Rs 1.4 lakh crore in the revised estimate. There are no signs of a fall in fertiliser prices, but the government has only budgeted for Rs 1.05 lakh crore fertiliser subsidy for the year 2022–23 (Table 11). This clearly means that the farmers are going to suffer a huge price increase in fertiliser costs in the coming year.

Notes

1. Kirankumar Vissa, “A Grim Future: What Happened to the Promise of Doubling Farmers’ Income by 2022?” 5 February 2022, https://thewire.in.

2. “Income and Debt Account of India’s Farmers – Explained”, 20 November 2021, https://www.indiatoday.in.

3. Kota Neelima, “Budget 2022: Will Modi Govt Address Issues Plaguing India’s Farmers?”, 29 January 2022, https://www.thequint.com.

4. 1983 figure from: Economic Survey, 2001–02: Social Sectors – Labour and Employment, http://indiabudget.nic.in. Remaining figures taken from: Santosh Mehrotra, Jajati K. Parida, “India’s Employment Crisis: Rising Education Levels and Falling Non-agricultural Job Growth”, October 2019, CSE Working Paper, https://cse.azimpremjiuniversity.edu.in.

5. For more on this, see: “The Kisans are Right. Their Land Is at Stake – Part 1”, Research Unit for Political Economy, January 26, 2021, https://rupeindia.wordpress.com.

6. Partha Sarathi Biswas, “After Highest-Ever Demand in 2020–21, Work Demand Under MGNREGS Sees a Dip”, 7 January 2022, https://indianexpress.com.

7. Shreehari Paliath and Shreya Raman, “Budget 2021 Not Enough to Boost Employment: Experts”, 3 February 2021, https://www.indiaspend.com.

8. Santosh Verma, Anisha Anustupa, “Budget for Rural Development – Does it Meet Expectations?”, 8 February 2022, https://www.newsclick.in.

9. “MNREGA Coverage Expanded during Lockdown, But Safety Net Inadequate for Districts that Need it the Most”, 1 December 2020, https://www.firstpost.com.

10. Ankita Aggarwal and Vipul Kumar Paikra, “Why MNREGA Wages are So Low”, 12 October, 2020, https://theprint.in. See also: “Increase in Notified MGNREGA Wages for 2021–22 Is Negligible in Comparison to the Pandemic Year, State Right to Work Activists”, 18 March 2021, https://www.im4change.org.

11. Partha Sarathi Biswas, op. cit.

12. “NREGA Sangharsh Morcha Demands a Hike in MGNREGA Budget for FY 2022–23”, 30 January 2022, https://im4change.org.

13. “With Budget 2022–23, Govt Has Once Again Failed Millions of Rural Citizens: NREGA Sangharsh Mocha”, 2 February 2022, https://thewire.in.