The Budget’s Approach to the Crisis Gripping the Country

1. External Accounts Situation

Let us begin our discussion of the Union Budget 2022–23 with a brief discussion of India’s external accounts situation. This is obviously an important part of any discussion about our economy, and the finance minister should mention the state of our external accounts, even if briefly, in her budget speech.

However, for the past few years, and this year too, the FM’s budget speech does not contain even a single line as regards the external accounts situation of our country! This is simply amazing, as a key aspect of our economic policy making for the last three decades is tackling our foreign exchange crisis.

Let us briefly explain. The Indian economy is entrapped in a huge foreign exchange crisis. As of end-September 2021, India’s external debt had gone up to $593.1 billion. That is huge – our country is one of the world’s most indebted countries. While the Economic Survey 2021–22 claims that our external accounts situation is comfortable, as our foreign exchange reserves are more than $600 billion, the security provided by our forex reserves is an illusion. Foreign exchange reserves of a country do not represent the foreign exchange earnings of that country. They are merely the total foreign money held by the government and central bank of a country, including all the foreign capital inflows that have come into the country. This implies that if foreign investors start withdrawing their money from the country, the foreign exchange reserves will fall and the economy can even sink into external account bankruptcy.[1] Therefore, the country’s foreign investors and foreign governments are in a position to impose conditionalities on the Indian economy. The two important conditionalities of the foreign investors are: i) Open up the economy to unrestricted inflows of foreign capital and goods; ii) Keep the fiscal deficit under control by restricting government spending, especially on welfare sectors.

Rather than confront this crisis facing the Indian economy, the Modi Government is meekly bowing to the dictates of foreign capital. This is the reason why it is permitting giant foreign corporations to take control of the most crucial sectors of the economy, like agriculture and retail—which is going to adversely impact the livelihoods of crores of people who depend for their livelihoods on these sectors.

This is also the reason why the Indian government refused to increase its spending and give reasonable relief to the people even at the peak of the pandemic crisis.

No wonder that the FM remains silent on our country’s external accounts situation.

Let us keep this discussion on our external accounts situation limited to this much and focus on the internal economic situation.

2. Unemployment and Poverty Crisis

The country is yet to recover from the deep unemployment and poverty crisis it has been pushed into due to the corona pandemic. To put it more accurately, the country’s economy was already in dire straits before the pandemic hit the country; the pandemic only worsened the situation. Before we begin our analysis of the budget, let us take a look at this crisis.

The country is facing is facing its worst unemployment crisis in the last several decades. The severity of the crisis can be gauged from the fact that the country recently saw its worst job riots in several years, in UP and Bihar. These riots were triggered because for the last two years, the govt has been delaying recruitment in the railways. But what is more important with respect to our discussion is an underlying figure—more than 1.25 crore people had applied for 35,000 job openings. This means that even if the posts had been filled, more than 99% of the applicants would still have been without a job. The number of disappointed candidates would still have been larger than the entire population of Belgium.

Therefore, the roots of the unemployment riots are not in the govt delaying railway recruitment, but in the fact that there are simply no jobs—which is why when a few jobs are advertised, tens of lakhs of youth rush to apply.

The govt is denying any unemployment crisis, citing unemployment figures. Firstly, God alone knows from where it is getting these figures—as the govt had stopped collecting unemployment data years ago.

The only unemployment data available are CMIE (Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, a leading private business information company) figures. According to the CMIE, unemployment rate has been rising consistently over the past few years—it was 4.7% in 2017–18 and 6.3% in 2018–19. Then, after the pandemic struck, crores of people lost their jobs—around 12 crore people according to CMIE estimates or more than one-fourth of the employed. When the lockdown was gradually lifted, jobs started recovering, but not to the level before the pandemic, and so unemployment remained at a high of 9.1% in December 2020. Since then, there has been a marginal recovery; nevertheless, the unemployment rate has remained above 7% during the past 6 months—rising to 7.9% in December 2021.

But unemployment figures don’t have any meaning for a country like India where the unemployment situation is so bad that a large number of people have simply given up looking for jobs because there aren’t any. These people are called discouraged workers, and are not included in the unemployment statistics—whereas they should be.

Therefore, a better indicator of the employment situation is employment rate—how many people of working age group are employed, that is, doing some job or the other.

- Employment rate = Total number of people employed / Total working age population

Over the past 5 years, between December 2016 and December 2021, India’s employment rate has come down from 43 per cent to 37 per cent. As a result, while India’s total working-age population has gone up over these five years by 12.5%, from 96 crores to 108 crores, the total number of employed has dropped about 2%—from 41.2 crores to 40.4 crores.[2] This means that at present, of 108 crore people, only 40 crore are employed. Of the remaining, a few crore, at the most 4 crore, would be in higher education and so genuinely not looking for a job. Most of the remaining are all actually unemployed—which means an unemployment rate of around 40% or so!

The actual employment situation in the country is far more worse than that suggested by the above figures, as more than 90% people are working in the informal sector. The overwhelming majority of them work in either insecure low paid jobs, with no social security, like in the construction sector or in roadside eateries or in tiny enterprises, or are self-employed—as street vendors or rickshaw pullers and autorickshaw drivers, as home workers making agarbattis and or rolling bidis at home, etc.—and earn barely enough to eke out a living. Why do all these people work in such low-paying jobs? Because there is no unemployment allowance in India. Therefore, people are forced to take up whatever jobs are available, or do any kind of work, to somehow earn something and stay alive. While unemployment surveys, including CMIE surveys, consider all these people to be ‘gainfully employed’, actually a very large number of them should be counted as unemployed. The unemployment rate would then go up to unimaginable levels – 60%, 70% or even more.[3]

Poverty

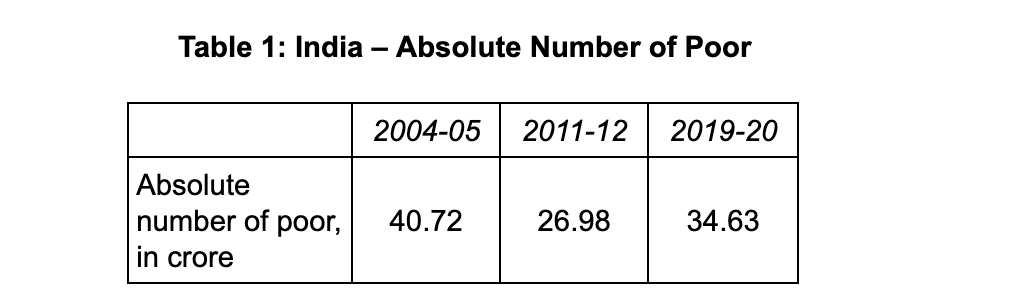

The Indian government has been conducting surveys to determine the poverty situation in the country since 1973. The surveys show that poverty in the country has continuously declined till 2011–12. After Modi came to power, he stopped the release of these survey data as poverty has been increasing during during his reign. A big hue and cry ensued, and the government was forced to release some data; some other data got leaked. The data show that for the first time since the 1970s, poverty in the country has risen during the period 2011–12 and 2019–20. The poor have increased in absolute numbers by as many as 7.6 crore in a matter of eight years.[4]

Other data too bear this out:

- According to a 2020 estimate by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), India has nearly nearly 19 crore people who suffer from serious hunger—about 14% of the population.

- The Global Hunger Index 2020 places India at 94 rank among 107 countries afflicted with mass hunger.

- The National Family & Health Survey of 2015–16 found that 59% of children up to 5 years of age were anaemic, as were 53% of all women—both indicators of malnutrition.

- Over 35% children were stunted and nearly 17% were wasted—both indicators of chronic malnutrition—according to the Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey (CNNS) carried out between 2016 and 2018 under the aegis of the health ministry.[5]

In other words, poverty situation was already dire even before the pandemic struck. The pandemic destroyed crores of jobs; studies have shown that the economic recovery that followed the lifting of the lockdown did not lead to full recovery of the jobs lost. Furthermore, most of the people who got jobs back suffered a loss in earnings, with many regular workers forced to take up informal jobs. With the govt giving a very miniscule relief package, obviously all this must have pushed crores of people into poverty.[6] A recent study by Oxfam corroborates this—it finds that the pandemic pushed around 4.6 crore people into extreme poverty in 2020. This number is half the global increase in poverty during the pandemic.[7]

This must have had a devastating impact on the malnutrition and hunger crisis. That is because children’s nutrition programs suffered because of schools—which provided mid-day meals—were closed. Anganwadi nutrition programmes that gave food to infants and pregnant and nursing mothers faltered and have barely recovered.

To make matters worse, inflation is accelerating even in the midst of massive unemployment and poverty.

Meanwhile, the rich have not just done well, they have done extremely well. We have pointed out in several other talks and articles that even during the pandemic, the Modi government has run the economy solely for the benefit of big corporate houses. Consequently, the rich have done extremely well even during the pandemic, and have cornered all the wealth gains even during this crisis period.

According to the Oxfam report mentioned above, during the pandemic years, even as 84 per cent of households in the country suffered a decline in their income in 2021, the number of country’s billionaires grew from 102 to 142, and their combined wealth more than doubled, from Rs 23.14 lakh crore to Rs 53.16 lakh crore during the period March 2020 to November 2021.[8]

The reason for this severe unemployment and poverty crisis is that the Modi Government has doled out a very inadequate relief package to tackle the corona pandemic. Total increase in spending by the Modi Govt during FY 2021 over FY 2020 is 4.3% of GDP (see Table 3). We can take this to be the total fiscal stimulus provided by the government to stimulate economic recovery. In comparison, the fiscal stimulus provided by other countries is more than double and even 3 to 4 times this. As a percentage of GDP, here is a snapshot of the relief packages provided by some developed countries: UK 9%, Spain 10.7%, Italy 13%, France 15.8%, Canada 16.4%, Australia 16.8%, USA 18.3% and Germany 20.3%. These were packages announced till November 2020.[9]

Let us now take a look at what the Budget 2022–23 has to offer.

3. The FM’s Approach

The 2022–23 union budget should have spelt out an economic strategy for reviving the economy and tackling the unemployment and poverty emergency gripping the country. But the FM does not even show cognizance of the problem. Her budget speech does not even mention the words unemployment or poverty.

The FM began her speech by claiming that the Indian economy is displaying a robust recovery, and is expected to grow by 9.2% for the year 2021–22, “highest among all large economies” as she put it.

The Economic Survey claims that with the “economic momentum building back” … “the Indian economy is in a good position to witness a real GDP growth of between 8.0–8.5% in 2022–23.”

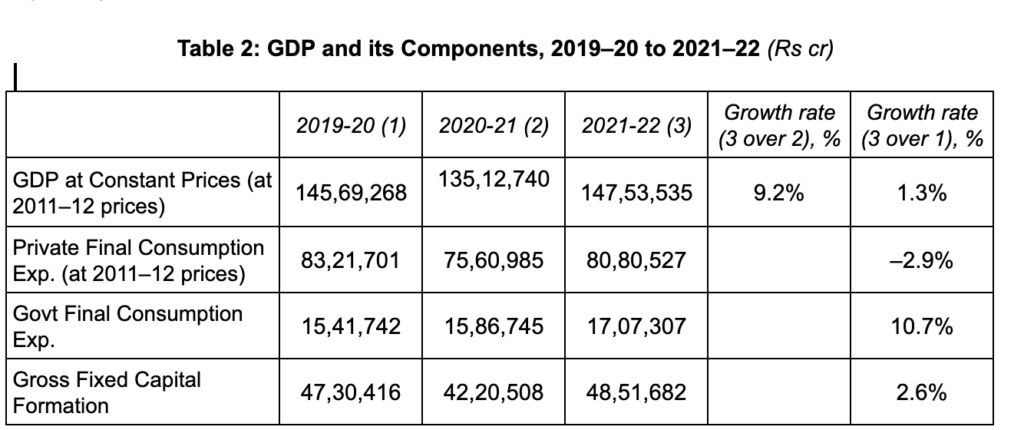

The near double-digit growth rate for the current year has little meaning, as the economy had sharply contracted by 7.3% in the previous year, 2020–21, which was also one of the sharpest among all the countries of the world. So, some recovery was only to be expected. What matters is the performance of the economy as compared to the pre-pandemic fiscal year 2019–20. And when we do so, we find that the GDP for 2021–22 is only 1.3% above the 2019–20 GDP (Table 2). This is hardly indicative of a robust recovery in the economy.

(Note: These figures are based on NSO press release of 7 January 2022. The FM has based herself on these figures. These figures have been further updated by the NSO in another press release of 31 January 2022.[10] We have used the latter figures for this article, but for this table we are using the 7 January figures.)

The Economic Survey claims that the “economic momentum building back”. Is the economy really on a path of sustained recovery? To analyse this, let us examine the most important components of the GDP. GDP in any economy equals private consumption + private investment + government expenditure (we are ignoring net exports as they are a relatively minor factor). Now, private investment depends upon growth of demand, implying growth of GDP, so for a sustained recovery, there must be an increase either in private consumption or in government expenditure.

As can be seen from Table 2, the little recovery that has taken place in 2021–22 is mainly due to a large increase in government expenditure, which has gone up by more than 10% over 2019–20.

At the same time, the table also shows that this so-called economic revival is not based on any significant recovery in the condition of the people. Private consumption continues to be below the 2019–20 level—it has fallen by nearly 3% over the past two years. Since the rich have not really suffered during the pandemic years—they have in fact done very well as mentioned above—the consumption of the better-off sections of the population must be back to pre-pandemic levels or even more. This only means that the consumption of the poor has declined by much more than 3% over the past two years.

The Economic Survey forecasts an 8 to 8.5% increase in real GDP for the coming year. The FM too claims that the economy is set on a path to sustained recovery. These projections can only be realised if the government greatly increase its expenditure. And, so far as the ordinary people are concerned, even if this does take place and there is indeed some economic recovery, they will only benefit from it if the government increases its spending in such a way that it leads to an increase in domestic consumption and puts purchasing power in the hands of the people.

Has the Budget 2022 done anything towards this? Let us now examine this.

4. Main Budgetary Strategy: Hike in Capital Expenditure

In Budget 2022–23, the FM claims that just like the previous year’s budget, this year too the centre-piece of her budget is sharp increase in capital expenditure driven by enhanced public investment. In her words,

“Capital investment holds the key to speedy and sustained economic revival and consolidation through its multiplier effect…. Public investment must continue to take the lead and pump-prime the private investment and demand in 2022–23.”

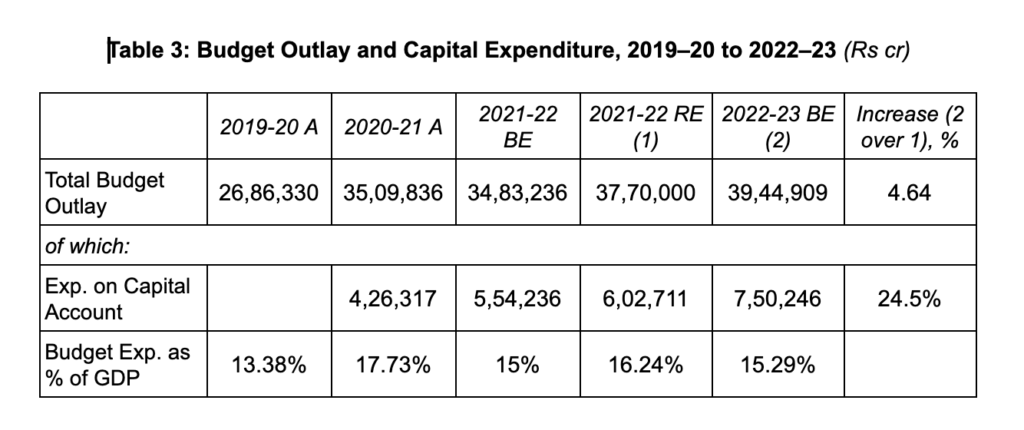

This is reflected in the budget figures too: capital expenditure did increase by 41 per cent from Rs. 4.3 lakh crore in 2020–21 (actuals) to Rs. 6 lakh crore in 2021–22 (RE) and is slated to rise by 24.5 per cent to Rs. 7.5 lakh crore in 2022–23 (See Table 3).

But an increase in capital expenditure by itself will not revive the economy—for that, what is needed is an increase in overall demand in the economy. And for that, what is important is not capital expenditure by itself, but overall expenditure. This is borne out from last year’ s economic performance. While last year, the capex rose by 41% (2021–22 RE over 2020–21 A), the overall budget outlay increased by only 7.4%, which did not lead to any significant recovery from unemployment crisis and poverty crisis gripping the country.

This year, the increase in capex is less ambitious—only 24%; but the increase in total budgeted government expenditure for 2022–23 is just 4.6 per cent higher than last year’s RE. That means the increase is below the rate of inflation, entailing a drop in real terms.

Therefore, in reality, the government has not really increased public investment to stimulate growth. With the FM herself admitting that public investment is necessary to pump-prime private investment, and with the FM not really increasing public investment, one wonders how is the government forecasting a real growth rate of 8–8.5 % this year ( as projected in the Economic Survey).

The Budget at a Glance foresees GDP growth rate to be 11% at current prices. This means that the FM also does not believe that the economy would grow by 8% this year—this figure is being cited only for public consumption.

As compared to the absolute figure for budget expenditure, budget expenditure as compared to GDP gives a better picture of how much the govt has increased public investment in the economy.

During Modi’s first term, this ratio was around 12–13% of GDP, then during the corona period it went up to 17.7% in 2020–21 Actuals, but has started falling again and has come down to 15.3% for this year (Table 3). This only means that the FM is rolling back whatever little stimulus she had given to the economy in FY 2020. For the FM, ALL IS WELL!

5. Centre’s Budgetary Revenues

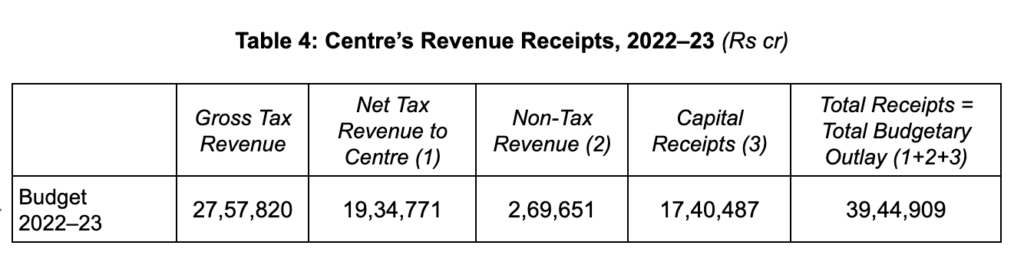

The total budgetary receipts of the government, which are equal to its budgetary outlay, include net tax revenue to Centre, non-tax revenue and capital receipts.

Budget 2022–23 estimates the gross tax revenue of the Centre to be Rs 27.6 lakh crore. After transfer to states, the net tax revenue to Centre is expected to be Rs 19.3 lakh crore. The total receipts, and hence the total budgetary outlay of the Central government in 2022–23, is Rs 39.45 lakh crore (Table 4).

India: Low tax revenue

Now, the fact of the matter is, the total tax revenue of the government is very low. This can be understood by comparing the total tax revenue of the Indian Government (Centre and States combined) as a proportion of GDP with other countries. India’s tax-to-GDP ratio (taking into consideration all taxes of the Centre and states) was is between 16–17%, according to the Chairman of the Fifteenth Finance Commission Chairman N.K. Singh.[11] In a moment of candidness, the Economic Survey 2015–16 had admitted that India’s tax-to-GDP ratio is lower than both the Emerging Market Economy (EME) and OECD averages, which are about 21% and 34% respectively.

The main reason for this low tax-to-GDP ratio is the huge tax concessions given by the Centre to big business houses and the rich, to the tune of several lakh crore rupees every year.

India: Inequitous tax revenue

Not only is the government’s tax revenue low, it is also grossly inequitous. The government gives huge tax concessions to the rich, and so collects the larger portion of its taxes from the poor. To understand this, let us take a look at the tax structure of the government.

There are two types of taxes, direct taxes and indirect taxes. Direct taxes are levied on incomes, such as wages, profits, property, etc., and so fall directly on the rich; while indirect taxes are imposed on goods and impersonal services, and so fall on all, both rich and poor. An equitable system of taxation taxes individuals and corporations according to their ability to pay, which in practice means that in such a system, the government collects its tax revenue more from direct taxes than indirect taxes.

In India, for every Rs 100 collected by the government (Centre + States combined) as tax revenue, less than Rs 40 comes from direct taxes (and the rest, Rs 60+, from indirect taxes).[12] This ratio is the exact opposite for most developed countries. This is admitted by the government too. The Economic Survey 2017–18 admitted that direct taxes account on average for about 70% of total taxes in Europe. It also admitted that India has much lower proportion of direct taxes in its total tax revenue as compared to other emerging market economies (except for China, which is a non-democratic country). An article in online news portal The Wire points out that India’s personal income tax collection both as a percentage of revenues and as a percentage of GDP is much lower than not just the USA and OECD but also the BRICS countries (as a percentage of GDP, personal income tax in USA was 10%, around 8% for the OECD countries, 5% for China, 3.6% for Russia, and 8.5% for South Africa, but was just around 1% for India.[13]

Most of the taxes collected by the States are in the form of indirect taxes. The direct taxes are mostly collected by the Centre. In the Centre’s tax revenue, the share of direct taxes has been falling under the Modi regime. The share of direct taxes in Centre’s gross tax revenue was 56% in 2014–15, 54.6% in 2018–19, and further to 51.5% in this year’s BE.

Increasing Violation of Federal Structure

The Centre’s and States’ finances are interlinked. The States are supposed to receive 41% of the ‘Divisible Pool’ of Centre’s tax revenues, defined as total tax revenue of the Centre minus the expenditure incurred for collecting taxes. But there is a loophole in this, which enables the Centre to transfer a lesser portion as taxes, and the Modi Government is blithely exploiting this. The loophole is, that taxes collected by the Centre in the form of cesses and surcharges are not shared with the States.

- Divisible Pool of Centre’s revenues = [Gross Tax Revenues of Centre – Cesses and Surcharges – Expenses incurred for collecting taxes]

- States’ Share of Centre’s Tax Revenues = Divisible Pool of Centre’ Revenues x 41%.

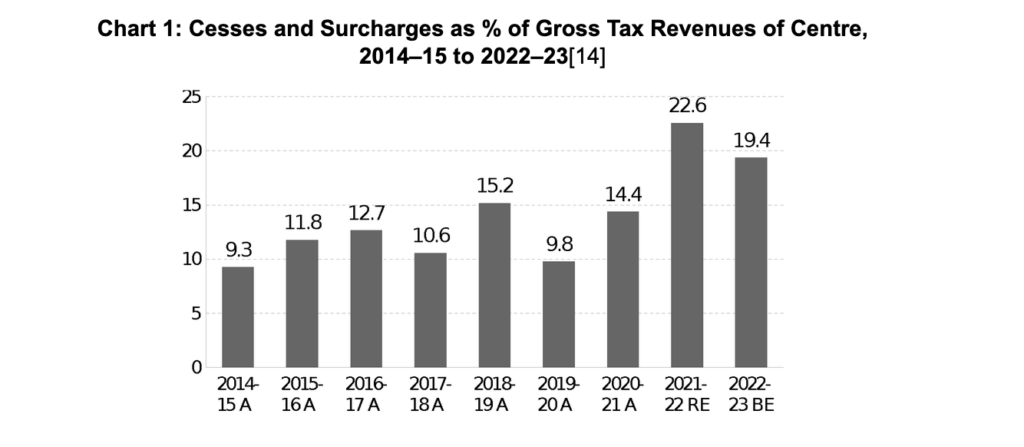

The Centre has increasingly been resorting to collecting more and more of its taxes as surcharges and cesses, so that it does not have to transfer a portion of these collections to States. The result of all these cesses and surcharges is that their share in the gross tax revenue of the Centre (excluding the GST compensation cess which is exclusively given to the States) has more than doubled, from 9.3% in 2014–15 to 19.4% in this year’s budget estimate (Table 3).

For 2022–23,

- Total cesses and surcharges = Rs 5.35 lakh crore

- Total gross tax revenues = 27.58 lakh crore

This means that the States are losing Rs 2.19 lakh crore in revenues this year due to this trick by the government. Total States’ share of Central tax revenues this year is Rs 8.17 lakh crore. A simple calculation shows that the States are going to suffer a loss of 21.1% in their share of Central tax revenues this year.

Of the total Central transfers to States, around 80% is Central taxes devolved to States, which are untied funds and States can use them as they wish. The remaining is grants-in-aid for schemes and other programmes. So, if the Centre resorts to tricks to reduce the tax transfers to the States, they are pushed into a corner, and have to approach the Centre for special funding. This gives the power to the Centre to play favourites, and penalise those States which oppose it politically—affecting the federal structure of the country. This is precisely what the Modi Government is doing.

Not only are the central cesses and surcharges violating federalism, the way in which the Centre is imposing them are inflationary. The most important components of these cesses are imposition of additional excise duty (road and infrastructure cess) and special additional excise duty (surcharge) on petrol and diesel, apart from cess on crude oil. Then, last year, the Centre imposed an Agriculture infrastructure and development cess also, which is levied on fuels too. Because of steep hikes in these cesses, total excise duty on petrol has gone up from Rs 9.48 per litre in 2014 to Rs 32.90 a litre now while the same on diesel has gone up from Rs 3.56 a litre to Rs 31.80. Subsequently, this has been cut by Rs 5 a litre on petrol and Rs 10 per litre; so the total incidence of excise on petrol currently is Rs 27.90 a litre and that on diesel is Rs 21.80. However, states get a share only from basic excise duty—which is only Rs 1.40 per litre on petrol, and Rs 1.80 per litre on diesel—which means states get only Rs 0.57 per litre from the excise duty on petrol, and Rs 0.74 per litre from diesel.

These massive hikes in petrol and diesel have resulted in price of petrol and diesel shooting up from Rs 71.41 for petrol and Rs 56.71 for diesel (as on May 14, 2014 in Delhi) to more than Rs 100 now—and this despite the fact that the base price for crude in a litre of petrol / diesel has fallen by between 25–30% during the Modi years.[15] Consequently, the earnings of the Centre from excise duties on petrol and diesel has zoomed from Rs 72,160 crore in 2014–15 to Rs 3.72 lakh crore in FY 2020–21. This figure amounts to 18.35% of the Centre’s gross tax revenues. Of this, states were given only Rs 19,972 crore. This means that the share of excise duties on petrol and diesel accounted for nearly 25% of the net Central tax revenues.[16]

Low General Revenue

Apart from huge tax concessions to corporate houses, the Centre has also been giving several other types of concessions to corporate houses, but for which it could have greatly increased its non-tax revenues. These transfers to the rich include loan write-offs, handing over control of the country’s mineral wealth and resources to private corporations in return for negligible royalty payments, transferring ownership of profitable public sector corporations to foreign and Indian private business houses at throwaway prices, direct subsidies to private corporations in the name of ‘public–private–partnership’ for infrastructural projects, and so on. These transfers of public wealth to private coffers also total several lakh crore rupees every year. This is actually the biggest scam in the country, many times more than the Nirav Modi or Vijay Mallya scam.

These huge concessions / subsidies / transfers being given to the rich, both in the form of tax concessions and non-tax concessions, are responsible for the government’s low revenues and low budgetary outlay. India’s total government revenue as percentage of GDP is amongst the lowest in the world. It is more than 40% for most countries of the European Union, going up to above 50% for countries like Belgium, France, Denmark and Finland. It is 29.7% for South Africa, 36.6% for Argentina and 31.6% for Brazil. The world average is 30.2%. But India ranks far below—the Indian Government’s total revenue is only 20.8% of GDP (this is total government revenues, Centre + States combined).

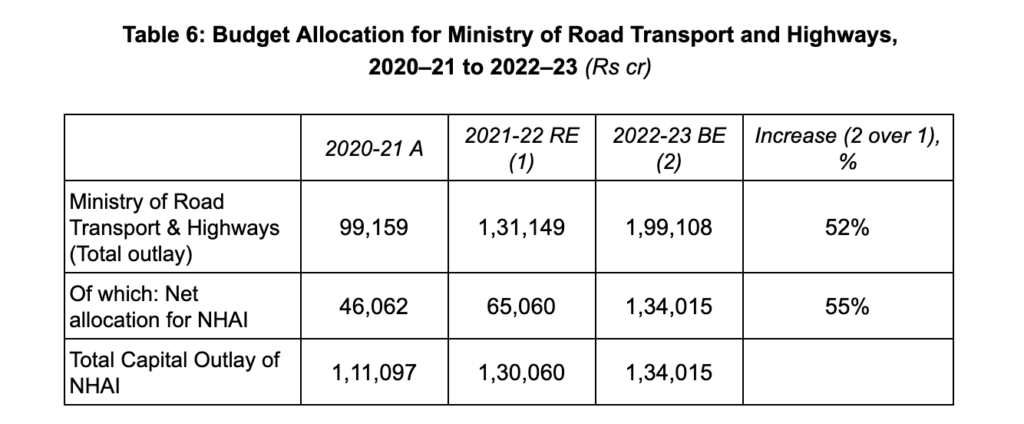

Let us discuss briefly one such subsidy given to corporates in the latest budget. The budget papers reveal that the government has hiked the allocation for Ministry for Road Transport and Highways by more than 50% (Table 6)

The biggest hike within this is a hike in the government’s capital expenditure for the National Highways Authority of India (NHAI). The NHAI constructs national highways. Till last year, around 50% of the capital outlay for NHAI’s national high construction programme was raised by NHAI as loans and bonds from the market, and the remaining 50% was funded by the Government of India (thus, for 2021–22 RE, government funded Rs 65,060 crore as equity support out of total NHAI capital outlay of Rs 1,30,060 crore, and the rest was raised by NHAI on its own account).[18]

For 2022–23, the NHAI’s capex is Rs 1,34,015 crore. But the government has decided to fully fund this programme! The NHAI is not going to raise any of this.

The implication of this is, that till last year, the NHAI’s highway construction programme was being partly funded by private entrepreneurs who were building the highways, and the government was only giving them what it called viability gap funding. The government logic behind this funding was that since the investment by the private sector on building highways was not profitable enough, that is, the toll collections were not enough, it was providing them financial support. This was thus nothing but direct government subsidy to the private investors investing in building roads.

This year, the government has decided to hike this subsidy to 100%! That is absolutely amazing!

Notes

1. For more on this, see our publication: “The Unemployment Crisis: Reasons and Solutions”, Lokayat, December 2020, available at lokayat.org.in.

2. “ExplainSpeaking: High Unemployment, a Common Factor in Poll-Bound States”, 11 January 2022, https://indianexpress.com.

3. For more on this, see our publication: “The Unemployment Crisis: Reasons and Solutions”, op. cit.

4. Santosh Mehrotra and Jajati Keshari Parida, “‘Pakoda’ Employment Has Increased Poverty Over the Last Eight Years”, https://thewire.in.

5. Subodh Varma, “Hunger Amidst Plenty—Tragedy Continues 75 Years After Independence”, Newsclick, August 29, 2021, https://www.newsclick.in.

6. Govindraj Ethiraj, “97% Of Indians Are Poorer Post-Covid”, 28 May, 2021, https://www.indiaspend.com.

7. “Taxing Extreme Wealth”, Factsheet Report, https://patrioticmillionaires.org.

8. “Oxfam Report: In 2021, Income of 84% Households Fell, But Number of Billionaires Grew”, 17 January 2022, https://indianexpress.com.

9. Emily Barone, “How the New COVID-19 Pandemic Relief Bill Stacks Up to Other Countries’ Economic Responses”, December 21, 2020, https://time.com.

10. Press Note On First Revised Estimates of National Income, Consumption Expenditure, Saving and Capital Formation for 2020–21, https://pib.gov.in.

11. “Our Tax-to-GDP Ratio Doesn’t Permit Latitude for Raised Public Outlays: NK Singh”, 13 November 2021, https://indianexpress.com.

12. “Direct and Indirect Tax Revenues of Central and State Governments”, RBI Publication, https://m.rbi.org.in.

13. Rajul Awasthi, “India’s ‘Billionaire Raj’ Era: Time to Reform Personal Income Tax”, September 20, 2017, https://thewire.in.

14. “In Search of Inclusive Recovery: An Analysis of Union Budget 2022–23”, CBGA 2022, https://www.cbgaindia.org.

15. Lydia Powell et al., “Retail Price of Petrol and Diesel in India: Crude Calculations”, October 09 2021, https://www.orfonline.org.

16. “Centre’s Excise Mop-Up from Petrol, Diesel Doubles to Rs 3.7 Lakh Crore in FY21”, November 30, 2021, https://www.zeebiz.com; “Central Govt’s Tax Collection on Petrol, Diesel Jumps 300% in Six Years”, March 22, 2021, https://www.business-standard.com.

17. “General Government Revenue (% of GDP) Data for All Countries”, Data Source – IMF, Year 2015, http://economywatch.com; OECD countries data also available at: “General Government Revenue”, https://data.oecd.org.

18. See Statement 26, Expenditure Profile, Union Budget 2022–23, https://www.indiabudget.gov.in.