The budget for 2020 is due. We have argued in articles published in Janata that imposition of a progressive wealth tax ranging from 2% on India’s dollar millionaires to 5% on India’s dollar billionaires would yield at least Rs 8 lakh crore in additional income for the government. Additionally, imposition of a modest inheritance tax of one-third of the value of the property inherited for only the country’s dollar millionaires would yield an additional revenue of Rs 5 lakh crore. This amount would be enough to finance good quality and free education for all children, good quality and free / affordable health care for all people, pension of Rs 2000 per month for all old people, and universal food security for all people.

Below are two articles written by leading economists justifying wealth tax and inheritance tax.

- A Wealth Tax: Because That’s Where the Money Is

Martin Hart-Landsberg

The bank robber Willie Sutton, when asked by a reporter why he robbed banks, is reputed to have answered, “Because that’s where the money is.” Which brings us to a wealth tax.

Transforming our economy is going to be expensive. And a tax on the wealth of the super wealthy is one way to capture a sizeable amount of money, which is why both Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren include the tax in their respective programs. The economists Gabriel Zucman and Emmanuel Saez estimate that Sanders’s proposed wealth tax would raise $4.35 trillion over the next decade, while Warren’s would raise $2.75 trillion.

Where the money is

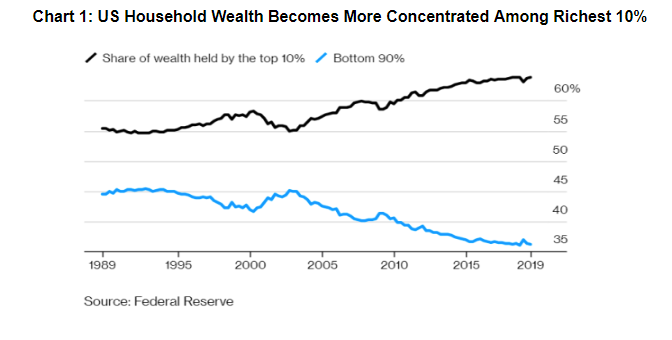

The concentration of wealth has steadily increased since the mid-1990s, as illustrated in Chart 1.

A recent Federal Reserve Bank study highlights the fact that the top 10 percent and even more so the top 1 percent of households have been especially successful in increasing their equity ownership in US public and private companies. For example,

“In 1989, the richest 10 percent of households held 80 percent of corporate equity and 78 percent of equity in noncorporate business. Since 1989, the top 10 percent’s share of corporate equity has increased, on net, from 80 percent to 87 percent, and their share of noncorporate business equity has increased, on net, from 78 percent to 86 percent. Furthermore, most of these increases in business equity holdings have been realised by the top 1 percent, whose corporate equity shares increased from 39 percent to 50 percent and noncorporate equity shares increased from 42 percent to 53 percent since 1989.”

It is worth emphasising that last point: the top 1 percent of households now control more than half of the equity in US businesses, public and private.

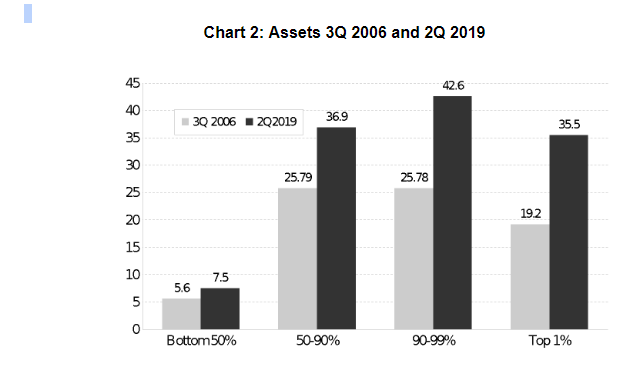

Chart 2 shows total wealth holdings for all US families as of the second quarter, 2019. The top 1 percent now own almost as much wealth as all the families in the 50th to 90th percentiles combined.

A comparison with the size and distribution of wealth in 2006 illustrates the rapid gains made by those at the top.

In 2006, the total wealth held by families in the 50th to 90th percentiles was slightly greater than that held by families in the 90th to 99th percentiles and significantly larger than those in the top 1 percent. But not anymore. And sadly, families in the bottom half of the distribution, whose wealth is predominately in real estate, have fallen further behind everyone else.

Time for a wealth tax

Recognising this reality, and the fact that this concentration of wealth was aided by a steady decline in top individual, corporate, and estate tax rates, both Sanders and Warren want to tax the super wealthy to generate funds to help pay for their key programs, especially Medicare for All. And, as an added bonus, to begin weakening the enormous political power of those top families.

Sanders would create an annual tax that would apply to married couple households with a net worth above $32 million—about 180,000 households in total, or roughly the top 0.1 percent. The tax would start at 1 percent on net worth above $32 million, with increasing marginal tax rates–a 2 percent tax on net worth between $50 to $250 million, a 3 percent tax from $250 to $500 million, a 4 percent tax from $500 million to $1 billion, a 5 percent tax from $1 to $2.5 billion, a 6 percent tax from $2.5 to $5 billion, a 7 percent tax from $5 to $10 billion, and an 8 percent tax on wealth over $10 billion. For single filers, the brackets would be halved, with the tax starting at $16 million.

Warren’s wealth tax would apply to households with a net worth above $50 million—an estimated 70,000 households. The tax would start at 2 percent on net worth between $50 million to $1 billion, rising to 3 percent on net worth above $1 billion. Her proposed tax brackets would be the same for married and single filers.

Zucman and Saez have calculated how some of the richest Americans would have fared if these wealth taxes had been in place starting in 1982. For example, Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, is currently worth some $160 billion. Under the Sanders plan his wealth would have been reduced to $43 billion. Under the Warren plan, it would be $87 billion.

As a New York Times article sums up:

“Over all, the economists found, the cumulative wealth of the top 15 richest Americans in 2018—amounting to $943 billion, using estimates from Forbes—would have been $434 billion under the Warren plan and $196 billion under the Sanders plan.”

Despite the fact that the super wealthy will still have unbelievable fortunes even if forced to pay a wealth tax, almost all of them are strongly opposed to the tax and determined to discredit it.

Challenges ahead

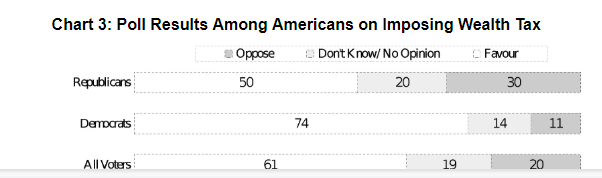

Polling done early in the year found strong support for a wealth tax (Chart 3). As Matthew Yglesias explains:

“Americans are . . . positively enthusiastic about Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s proposal to institute a wealth tax on large fortunes, according to a new poll from Morning Consult. Their survey finds that . . . the wealth tax scores a crushing 60–21 victory that includes majority support from Republicans.”

Of course, this kind of support was registered before the start of any serious media effort to raise doubts about its effectiveness. Recently, a number of wealthy business people and conservative economists have begun to make the case that a wealth tax is a radical measure that will harm the economy. Some point to the fact that many countries that once used the tax have now abandoned it. Twelve OECD countries had a wealth tax in 1990, now only three do (Norway, Switzerland, and Spain). France, Germany, and Sweden are among the majority that no longer use it.

However, as Zucman and Saez explain, this fact does not mean that a wealth tax would not work in the US For example, in some countries it was the election of conservative governments philosophically opposed to such taxes that led to their elimination. More substantively, they highlight four problem areas that tended to undermine the effectiveness of and support for national wealth taxes in Europe and why these should not be a major problem for the US

First, European countries have their own separate tax laws and member states do not tax their nationals living abroad. Thus, a wealthy person living in a country with a wealth tax could easily move to a nearby country without a wealth tax and escape paying it. And many have. But, as the economists note,

“The situation in the United States is different. You can’t shirk your tax responsibilities by moving, because US citizens are responsible to the Internal Revenue Service no matter where they live. The only way to escape the IRS is to renounce citizenship, an extreme move that in both Warren’s and Sanders’s plans would trigger a large exit tax of 40 percent on net worth.”

Second, European governments tolerated a high level of tax evasion. Until last year, they did not require banks in Switzerland or other tax havens to share information about deposits with national tax authorities. This made it easy for the wealthy to hide their assets. The US is in a better situation to avoid this outcome. The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, signed in 2010, requires foreign financial institutions to send detailed information to the Internal Revenue Service about the accounts of US citizens each year, or face sanctions. Almost all foreign banks have agreed to cooperate.

Third, European wealth taxes had many exemptions and deductions. In contrast, there are none in the proposed plans by Warren and Sanders. Zucman and Saez highlight the French program that was in place from 1988 to 2017 as a prime example:

“Paintings? Exempt. Businesses owned by their managers? Exempt. Main homes? Wealthy French received a 30 percent deduction on those. Shares in small or medium-size enterprises got a 75 percent exemption. The list of tax breaks for the wealthy grew year after year.”

Fourth, European wealth taxes fell on a considerably larger share of the population than would the proposed plans by Warren or Sanders. In Europe, “wealth taxes tended to start around $1 million, meaning they hit about 2 percent of the population, compared with about 0.1 percent for the proposed US plans.” This broader reach of the European wealth taxes helped to generate popular pressure to weaken them, leading to their eventual removal. The more limited reach of the proposed US plans should help to blunt that development in the US

We can certainly expect a fierce debate over the viability and effectiveness of a wealth tax as the campaign season continues, especially if Sanders or Warren becomes the Democratic Party nominee for president. We should be prepared to advocate for the tax as one important way to ensure adequate funding of needed programs. But we should also take advantage of the debate to shine the brightest light possible on the growing and already obscene concentration of wealth in the US and even more importantly on the underlying and destructive logic of the capitalist accumulation process that generates it.

(Martin Hart-Landsberg is Professor Emeritus of Economics at Lewis and Clark College, Portland, Oregon.)

Editor’s note:

While the US is debating the imposition of a substantial wealth tax, in India, wealth taxation, which was always minuscule, was actually abolished by the Narendra Modi government. In addition, there have been substantial reductions in taxes on corporate profits and on capital gains. In fact, the latest example of such largesse was when the Modi government recently gave tax concessions worth Rs 1.5 lakh crore to the corporate sector as a means of stimulating the economy! This has further added to the wealth of the corporate sector.

One way of getting the economy out of its current crisis, without further accentuating wealth inequality, would be to enlarge government expenditure and finance it by taxing corporate wealth (which would not even affect the inducement to invest of the corporate sector). But the Modi government, which is sustained by a corporate-Hindutva alliance, can scarcely be expected to do that.

Why Even Capitalist Economists Can’t Justify Inheritance of Wealth

Prabhat Patnaik

If a headload worker were to ask a mainstream capitalist economist “Why does Ambani have so much wealth but I do not?”, that economist’s answer would be that Ambani has certain “special qualities” which the headload worker lacks. Mainstream economists, however, are not all agreed on what exactly these “special qualities” are that are supposed to explain wealth inequalities.

These “special qualities” that supposedly explain a person’s being wealthy must be independent of the fact of that person’s being wealthy, if this explanation is to have logical soundness. In a capitalist economy, for instance, capital accumulation occurs, and hence wealth increases over time. The working people, whose incomes are too low even for their subsistence, have little scope for saving, and since saving ipso facto entails addition to wealth, they cannot add to their wealth, and hence even acquire any wealth to start with.

It follows, therefore, that an explanation of why Ambani has wealth while the headload worker does not, which locates Ambani’s “special quality” in the fact of his being more thrifty, i.e. saving more, than the headload worker, is logically flawed. This is because if the headload worker had as much wealth as Ambani has, then he would have been as thrifty as, if not even more so, than Ambani.

Being thrifty, in other words, is a quality of all wealthy people, since they cannot possibly consume all the income that their wealth fetches them. Amban being more thrifty, therefore, is part and parcel of his being wealthy; it is not any “special quality” and cannot explain why a man called Ambani should be wealthier than a headload worker. The “special quality”, in short, has to be independent of the fact of Ambani’s possessing wealth.

Likewise, consider Prime Minister Narendra Modi calling capitalists “wealth creators”. This, of course, is an absurd description of a social process. But let us ignore this absurdity for a moment and accept this description for argument’s sake. The point is that it does not explain why some persons called (Mukesh) Ambani or (Gautam) Adani should be “wealth creators” and not the person who currently happens to be a headload worker.

One “special quality”, which the capitalist economist Joseph Schumpeter had emphasised, was innovativeness, i.e. the capacity to introduce “innovations”, within which he included new methods of production, new products, new markets and such like. He had drawn a distinction between “inventions” and “innovations”, the former referring to the development of knowledge about the new processes and products, and the latter to the practical use of this knowledge.

While “inventions” occurred independently in society, the capacity to introduce these inventions into the production process required a “special quality”, which consisted in the ability to identify and pick up a profitable opportunity; this “special quality” was possessed by only a few, whom he called “entrepreneurs”.

Entrepreneurship, according to Schumpeter, had nothing to do with whether a person was wealthy or not, but entrepreneurship was the reason for the acquisition of wealth since the first to introduce a new process or product stole a march over others and became rich. His explanation, therefore, was not logically flawed as the “thrift” argument was.

Schumpeter also argued that existing firms tend to be set in their ways of thinking and less prone to trying out new processes and products etc., because of which entrepreneurs came from outside the ranks of existing firms; they started new firms and made a fortune by introducing innovations. He argued, therefore, that while wealth inequality existed in a capitalist society, the composition of the top wealthy group of individuals, i.e. the identity of those constituting, say, the top 5% of the wealthiest, kept changing over time.

Schumpeter’s theory, which borrowed much from Karl Marx, is fundamentally unsound; but we shall not go into it here. Besides, even Schumpeter admitted that in modern capitalism, where firms had research laboratories attached to them, both inventions and innovations were not independent of the size of the firms and hence of the wealth already possessed by those who owned the firms. This made his theory inadequate for explaining why some were wealthy and others were not since it made addition to wealth depend upon the wealth already possessed.

But let us ignore all these problems and assume with Schumpeter that the wealthy are wealthy because they have a “special quality” which is “innovativeness”, or what he called “entrepreneurship”.

But this fact neither explains nor justifies why the children of the wealthy should also be wealthy. There is no “special quality” that these children display which could account for their possessing wealth; the reason they possess wealth, therefore, has entirely to do with a social arrangement whereby wealth is allowed to be inherited by children from parents, an arrangement which has no economic rationale whatsoever.

Of course, it may be thought, again taking Schumpeter’s explanation to illustrate the point, that if wealth was not allowed to be passed down to children, then there would be no incentive for the “entrepreneurs” to introduce “innovations”, that inheritance laws were a price to be paid for “progress” under capitalism.

But “incentives” are completely irrelevant for explaining “innovativeness” in Schumpeter’s or any other similar theory. If a new process is available, but is not introduced into the production system by one firm, then it would be introduced by another who would outcompete and replace the first; the motivation for introducing innovations, therefore, lies in competition and not in any incentives. In other words, the pace of introduction of innovations according to all these capitalistic theories, will not be affected one iota even if the whole of the wealth of the “entrepreneurs” is taxed away at their death.

True, if an invention is under the monopoly control of some firm, then that firm would not introduce it into the production system, in the absence of adequate “incentives”, such as the ability to pass on wealth to children and grandchildren; but then the explanation of wealth has shifted from “innovativeness” to monopoly; and if monopoly is the explanation of wealth then it cannot be justified, even according to capitalist theory, in a democratic society (which is why there are anti-trust laws and anti-monopoly measures).

In fact, if monopoly is accepted as an explanation of wealth, then capitalist theory has to accept the validity of socialist economics, which traces the origin of surplus value, the source of accumulation under capitalism, to the monopoly ownership of the means of production by a class of capitalists.

Some capitalist economists may claim that because of economies of scale the size of research and production establishments has to be large and this is the reason for the existence of monopolies, so that one need not shed tears about their existence; they are essential for “progress” in today’s world and that this explains and justifies permanent wealth inequalities. This, however, is an erroneous argument, since large scale of production does not necessarily mean large private wealth inequalities. Large-scale production can be carried out where ownership is dispersed or ownership is with the State.

It follows, therefore, that inheritance of wealth cannot be justified by capitalist theory itself. It is a social arrangement for which there is no economic rationale, even according to capitalist theory.

We have looked only at Schumpeter’s theory; but the same can be said about any other explanation of wealth inequalities, namely, that no logically valid explanation of wealth inequality in society advanced by any strand of capitalist theory can possibly justify the institution of inheritance of wealth.

While capitalist theory cannot justify the institution of inheritance, this institution is what prevails and is insisted upon by the capitalists. But since the building of a democratic society requires keeping wealth inequalities in check, the need to confront capitalists through the impost of substantial inheritance taxes cannot be denied even by capitalist theory. The fact that in societies like ours there is scarcely any inheritance taxation speaks volumes about the bad faith of our governments.

(Prabhat Patnaik is Professor Emeritus at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.)