The so-called “emergency” in Malaya – now Malaysia – between 1948 and 1960 was a counter-insurgency campaign waged by Britain against the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA).

The MNLA sought independence from the British empire and to protect the interests of the Chinese community in the territory. Largely the creation of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), the MNLA’s members were mainly Chinese.

But although the war in southeast Asia has long been presented in most British analyses as a struggle against communism during the cold war, the MNLA received very little support from Soviet or Chinese communists.

Rather, the major concern for British governments was protecting their commercial interests in the colony, which were mainly rubber and tin.

A Colonial Office report from 1950 noted that Malaya’s rubber and tin mining industries were the biggest earners in the British Commonwealth. Malaya was the world’s top producer of rubber, accounting for 75 per cent of the territory’s income, and its biggest employer.

As a result of colonialism, Malaya was effectively owned by European, primarily British, businesses, with British capital behind most large Malayan enterprises. Some 70 per cent of the acreage of rubber estates was owned by European, primarily British, companies.

Malaya was described by one British Lord in 1952 as the “greatest material prize in South-East Asia”, mainly due to its rubber and tin. These resources were “very fortunate” for Britain, another Lord declared, since “they have very largely supported the standard of living of the people of this country and the sterling area ever since the war ended”.

He added: “What we should do without Malaya, and its earnings in tin and rubber, I do not know”.

The insurgency threatened control over this “material prize”. The Colonial Secretary in Britain’s Labour government, Arthur Creech-Jones, remarked in 1948 that “it would gravely worsen the whole dollar balance of the Sterling Area if there were serious interference with Malayan exports”.

The Labour government of Clement Attlee dispatched the British military to the territory in 1948 in a classic imperial role, largely to protect those commercial interests.

“In its narrower context”, the Foreign Office observed in a secret file, the “war against bandits is very much a war in defence of [the] rubber industry”.

Political reform

The roots of the war lay in the failure of the British colonial authorities to guarantee the rights of the Chinese in Malaya, who made up around 40 per cent of the population. By 1948 Britain was promoting a new federal constitution that would confirm Malay privileges and consign about 90 per cent of Chinese to non-citizenship.

Under this scheme, the British High Commissioner would preside over an undemocratic, centralised state where the members of the Executive Council and the Legislative Council were all chosen by him. The political path to serious reform for the Chinese was therefore effectively blocked.

The Malayan Communist Party, which was anyway agitating for an uprising, either had to accept that its future political role would be very limited, or go to ground and press the British to leave.

An insurgent movement was formed out of one that had been trained and armed by Britain to resist the Japanese occupation during the Second World War. The Malayan Chinese had offered the only active resistance to the Japanese invaders.

The MNLA, drawn largely from disaffected Chinese, received considerable support from poor Chinese peasant farmers or “squatters”, who numbered over half a million.

Many were attracted to the insurgency since Malay politicians were threatening to evict them from their homes on the rubber estates to make way for replanting. Other squatters living in forest reserves were rounded up in mass arrests.

The reality of the war

In combating an insurgent force of 3,000-7,000, the key year was 1952. It was then that Sir Gerald Templer, a former director of military intelligence and vice chief of the Imperial General Staff, was appointed High Commissioner in Malaya by prime minister Winston Churchill.

Templer declared that “the hard core of armed communists in this country are fanatics and must be, and will be, exterminated”.

Heavy bombers had been brought into the war, dropping thousands of bombs of up to 4,000lb on insurgent positions. Britain conducted 4,500 air strikes in the first five years of the conflict.

In October 1951 the insurgents managed to ambush and kill the High Commissioner, Sir Henry Gurney. Atrocities were committed on both sides and the insurgents often indulged in horrific attacks and murders.

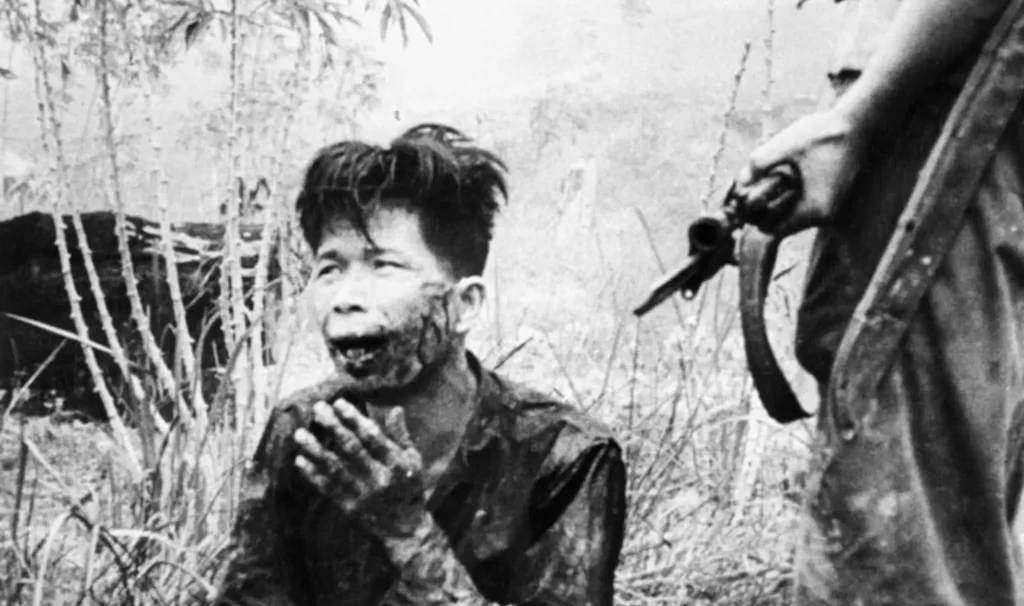

A young British officer commented that, in combating the insurgents: “We were shooting people. We were killing them…This was raw savage success. It was butchery. It was horror.”

Running totals of British kills were published and became a source of competition between army units. One army conscript recalled that “when we had an officer who did come out with us on patrol I realised that he was only interested in one thing: killing as many people as possible”.

Succession of killings

The most well-known atrocity was committed at the village of Batang Kali, north of the capital Kuala Lumpur, in December 1948 when the British army slaughtered 24 Chinese, before burning the village.

The British government initially claimed the villagers were guerrillas, and then that they were trying to escape, neither of which was true.

A Scotland Yard inquiry into the massacre was called off by the Edward Heath government in 1970 and the full details have never been officially investigated. The British government still refuses to hold a public inquiry.

Christopher Bayly and Tim Harper note that while Batang Kali was exceptional in its scale, “it was part of a continuing succession of killings on the estates, in the villages and along the roadsides”.

Decapitation of insurgents was also practised – intended as a way of identifying dead guerrillas when it was not possible to bring their corpses in from the jungle. A photograph of a Marine commando holding two insurgents’ heads caused a public outcry in the UK in April 1952.

The Colonial Office privately noted that “there is no doubt that under international law a similar case in wartime would be a war crime”.

Dyak headhunters from Borneo were brought in to work alongside the British forces. Templer suggested Dyaks should be used not only for tracking “but in their traditional role as head-hunters”.

The Colonial Office observed that, because of the recent outcry over this issue, “it would be well to delay any public statement on this matter for some months”.

Brute force

Templer famously said in Malaya that “the answer lies not in pouring more troops into the jungle, but in the hearts and minds of the people”. Despite this rhetoric, British policy succeeded because it was highly repressive, and really about establishing control over the Chinese population.

The centrepiece of this was the “Briggs Plan”, named after General Harold Briggs who was appointed Director of Operations in 1950. His “resettlement” programme involved the removal of over half a million Chinese squatters into hundreds of “new villages”, which the Colonial Office referred to as “a great piece of social development”.

Brian Lapping describes in his study of the end of the British empire what the policy meant in reality: “A community of squatters would be surrounded in their huts at dawn, when they were all asleep, forced into lorries and settled in a new village encircled by barbed wire with searchlights round the periphery to prevent movement at night.”

He adds: “Before the ‘new villagers’ were let out in the mornings to go to work in the paddy fields, soldiers or police searched them for rice, clothes, weapons or messages. Many complained both that the new villages lacked essential facilities and that they were no more than concentration camps”.

“Resettlement” offered further opportunities. One was a pool of cheap labour available for employers. Another was that, as a Malayan government newsletter said, it could “educate [the Chinese] into accepting the control of government”.

A key British war measure was inflicting “collective punishments” on villages where people were deemed to be aiding the insurgents. In March 1952, at Tanjong Malim in Perak state of western Malaya, Templer imposed a 22-hour house curfew, banned everyone from leaving the village, closed the schools, stopped bus services and reduced the rice rations for 20,000 people.

Psychological warfare

Former British official in Malaya, Brian Stewart, has written of the UK’s “psychological warfare” during the conflict which involved willingness to “exploit any propaganda opportunities”.

British officials established a Chinese newspaper “to put across every form of government message”, and pamphlets were distributed in villages to persuade insurgents to surrender. Stewart refers to “huge and successful psywar and deception operations”.

As part of this, UK officials distributed some 50m leaflets in 1949 alone, conducted “continuous radio propaganda” and circulated 4m copies of newspapers. By 1953, the number of anti-communist leaflets distributed was 93m, of which 54m were dropped by the Royal Air Force.

One key message was to counter the notion that “Britain cares little for the people of Malaya, only the rubber she produces”.

The “emergency” was never described by the British authorities as a war because to do so would have required the government, rather than private insurance companies, to compensate the rubber plantations and tin mines for the damage.

Foreign minister Robert Scott wrote in 1950 that the decision to call the insurgents ‘bandits’ or ‘terrorists’ “was taken originally because of the insurance implications of the words ‘insurgents’ or ‘rebels’ or ‘enemy’”.

Popular uprising

British officials were also keen to avoid any words which might suggest a popular uprising, and always played down the political roots of the rebellion. “On no account should the term ‘insurgent’, which might suggest a genuine popular uprising, be used”, Colonial Office official JD Higham stated.

In 1952 a defence ministry memorandum stipulated that, from now on, the insurgents – previously usually referred to as “bandits” – would be officially known as “communist terrorists” or CTs.

British planners at certain times feared that communism in Malaya might overturn British rule but there was never any question of military intervention by either the USSR or China, and neither did Moscow or Peking provide material support to the insurgents.

“No operational links have been established as existing”, the Colonial Office reported four years after the beginning of the war.

The British feared the Chinese revolution of 1949 might be repeated in Malaya. As the Economist described, the significance of this was that communists “are moving towards an economy and a type of trade in which there will be no place for the foreign manufacturer, the foreign banker or the foreign trader”.

At independence for Malaysia in 1957, the UK handed over formal power to the traditional Malay rulers and fostered a political alliance between the United Malay National Organisation and the Chinese businessmen’s Malayan Chinese Association.

Britain achieved its main aims, defeating the insurgents and essentially preserving its commercial interests.

Probably to cover up the extensive brutality of the war, which coincided with similarly vast repression in Kenya, British officials subsequently destroyed official documents on the war or refused to fully release them to the National Archives, along with other episodes at the “end of empire”.

We will probably never know the true, full story of this forgotten war.

(Mark Curtis is the editor of Declassified UK, and the author of five books and many articles on UK foreign policy. Courtesy: Declassified UK, a leading media organisation uncovering the UK’s role in the world. It investigates Britain’s military and intelligence agencies, its most powerful corporations and their impact on human rights and the environment.)