The Reason For BJP’s Victories in State Polls Is Mundane. Misreading It Will Only Benefit Them

Prem Shankar Jha

The Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP’s) jubilation over its victories in the Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh elections, and the near-panic that defeat has sown in the Congress, are measures of the increasing fragility of our democratic system. It shows that even after 16 Lok Sabha and innumerable Vidhan Sabha elections, neither party’s leaders, nor the country’s media pundits understand how the simple majority voting system (SMS) – that our constitution makers adopted in 1948 – works.

Had the Congress understood this, it would have known from the start that the elections were likely to swing the BJP’s way in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, and possibly Chhattisgarh, for exactly the same reason they had swung the Congress’ way in 2018. This reason is a phenomenon that political scientists, especially those who have studied Indian politics, have labelled the “anti-incumbency factor”.

The anti-incumbency factor is no more than an accumulation of disenchantment with the ruling government that arises when it fails to meet the expectations of all of those who voted for it in the previous elections. This makes a proportion of them decide to try their luck with the other side in the next election.

The impact of the anti-incumbency factor is much greater in the SMS than it is in proportional representation. This is because it invariably magnifies the ratio of seats won by the largest party to the votes cast for it and correspondingly reduces it for all the remaining parties. In the theoretical limiting case, where the vote is equally divided between all contending parties, an increase of even 0.1% in the vote share of one party will give it 100% of the seats. The seat-to-vote magnification then is close to infinite.

SMS has one important advantage over proportional representation, the other widely used system of voting in democracies. The advantage is that the compression of seats in relation to votes gets more pronounced as the political parties get smaller. Over time, this forces the fringe parties to merge with their closest ideological neighbours in order to retain some say in policy making. This need for compromise discourages the adoption of ideological – as distinct from pragmatic – programmes of governance.

As a democracy matures, this creates a two-party system in which both parties have shed extreme ideological positions in order to woo the uncommitted vote at the centre. In a fully mature system, therefore, even a small increase in the vote share of one party enables it to win a disproportionately larger number of seats.

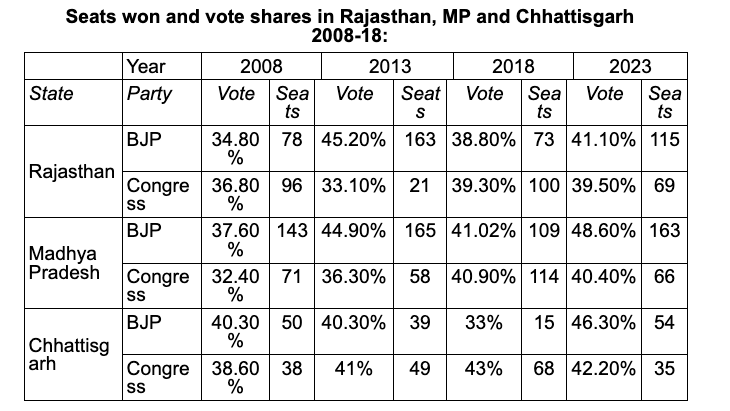

That is what happened in the elections this year. In Rajasthan, the BJP won 115 seats against 73 in 2018, an increase of over 60%. But this was brought about by a mere 2.3% rise in its vote share. The Congress, on the other hand, lost 31 of the 100 seats it had won in 2018 despite increasing its share of the vote by 0.2%.

In Madhya Pradesh, the BJP’s seats increased from 109 in 2018 to 163 this year. While this increase came on the back of a 7.5% rise in its vote share, the victory was at the expense of a large number of smaller parties as the Congress’ vote share only fell by 0.5%

The table below shows that this is not the first time there has been such anti-incumbency swings in these states. The Congress won the election in Rajasthan in 2008, lost it in 2013, won again in 2018 and lost again this year. The BJP has shown the obverse pattern. The common feature of all the elections is the notable feature of all of these elections has been that small shifts in votes have caused huge gains and losses in seats. Both the triumphalism in the BJP, and the loss of self-confidence in the Congress this year stem from the seat count alone. The Congress voter base has remained utterly stable. It is the the BJP’s vote share that has risen. This has not taken place at the Congress’ expense, but at that of other smaller parties which have habitually attached themselves to the dominant party in their state.

Both the triumphalism in the BJP, and the loss of self-confidence in the Congress this year stem from the seat count alone. The Congress voter base has remained utterly stable. It is the the BJP’s vote share that has risen. This has not taken place at the Congress’ expense, but at that of other smaller parties which have habitually attached themselves to the dominant party in their state.

What the Congress needs to take note of is that the shift of the vote of independents and smaller parties has been mainly towards the BJP, especially during the past decade. Over these four elections, approximately 10% of the vote that used to go to smaller parties and independents has shifted to the Congress and the BJP. But of the this 10%, two thirds has gone to the BJP alone.

This is the impact that Modi’s relentless drive to polarise the vote on communal lines has had. It is not enough to create Bharat. But it has sounded a warning to the vast majority of Indians who have so far taken Indian secularism and ethnic diversity for granted that both are now in deadly danger.

For secular India, forming the INDIA alliance was an essential first step. But its hopes will be dashed if it remains the last. Congress present Mallikarjun Kharge’s statement that INDIA needs to “rebuild and revive itself” shows how close INDIA had come to becoming moribund when the shock of the Vidhan Sabha defeats hit it.

That revival needs a clearly articulated and well publicised basis for the allocation of seats among its members; a common programme; a common platform from which to project it; and a strong research team that identifies issues and collects the data needed to expose the BJP’s failure to meet Modi’s promises, and to show how the INDIA alliance will meet the peoples’ most pressing needs.

Above all, it needs to show its unity in action. In the last three months, Modi’s administration has attacked every leader of the INDIA alliance who is capable of formulating such a response – be it Sonia Gandhi, Rahul Gandhi, Arvind Kejriwal, Manish Sisodia, or Mahua Moitra – with not a peep out of any member of the alliance in their defence.

This absolute silence is creating a walkover for Modi and his brand of Hindutva in the next Lok Sabha elections. INDIA has only four months left in which to break its paralysis and create the alternative image of India’s future that the majority of India’s people are hungering for.

(Prem Shankar Jha is a veteran journalist. Courtesy: The Wire.)

The Myth of BJP’s Hat-Trick and What the Statistics Really Say

Yogendra Yadav

When the prime minister said “hat-trick” about the recent assembly elections, everyone repeated “hat-trick” as if this conclusion required no questioning. By the next morning, the message spread across the country that after the victory in three states, no one can stop the Bharatiya Janata Party from winning the Lok Sabha elections for a third time. BJP supporters are already celebrating; opponents are dejected. But no one has stopped to ask, is this conclusion true?

This is how psychological games are played and won. Inflate a small balloon of truth so big that every contradictory truth is hidden behind it. Even before the fight starts, if the opponent’s morale is shattered, the match is likely to become a walk over. Therefore, it is important that we examine this claim with a cool mind.

Step 1: Start with the Election Commission website. Add the total votes received by all the parties in the four states for which results were declared on December 3. The BJP, which is blowing the trumpet of victory, has got a total of 4,81,33,463 votes, whereas the Congress, which was “defeated” in the elections, has got 4,90,77907 votes. That means, overall, the Congress has got about 9.5 lakhs more votes than the BJP. Still, all discussions seem to be assuming that the BJP has completely destroyed the Congress.

If we look at the number of seats in the three Hindi-speaking states which the BJP has won, in fact there is not much difference in the number of votes. In Rajasthan, the BJP has got 41.7% of the votes, while the Congress has got 39.6% votes. The difference, then, is only 2%. In Chhattisgarh the difference is 4% – BJP has 46.3% votes while the Congress has 42.2% votes. Only in Madhya Pradesh is the difference a little higher, at more than 8% – the BJP got 48.6% votes and Congress 40% votes. Despite losing in all three states, Congress has got 40% or more of the votes, from where it will not be very difficult to make a comeback.

The overall lead that the BJP has got in all three Hindi-speaking states is compensated by only one Telangana. In Telangana, the Congress party got 39.4% (more than 92 lakh) votes, while the BJP got 13.9% (less than 32 lakh) votes. In a state where the Congress was on the verge of being out of the electoral race after 2018, the party reaching the top is a sign of political vitality.

Step 2: Look back on history to test the hat-trick myth. For the last two decades, Lok Sabha elections have been held within a few months of the elections in Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh. Last time in 2018, the BJP had lost in these three states. But then neither the prime minister nor the media claimed that the BJP’s defeat in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections was certain. When parliamentary elections were held, the BJP won a landslide victory in these three states and the rest of the Hindi belt.

Similarly, while the Congress lost in these three states in 2003, it achieved an unexpected success in the 2004 Lok Sabha elections just a few months later. This means that the nature of elections for assemblies and the Lok Sabha are different, and it would be wrong to draw conclusions about the Lok Sabha directly from the assemblies. If the BJP can reverse this trend, then why not the Congress?

Step 3: Look at the equation of change of power in 2024. The BJP is dependent on these three states of the Hindi belt, but the opposition’s hopes do not rest on them. The electoral mathematics of the INDIA alliance depends on reducing the BJP’s seats in Karnataka, Maharashtra, Bihar and West Bengal. Out of 65 seats in Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan, the BJP already has 61 in its account and the Congress has only three. That means the BJP’s challenge is to retain all these seats and, if possible, get more than the four seats it had won in Telangana. On the other hand, the Congress has nothing to lose in these states. This means that from a national election point of view, the BJP has not achieved anything new in these assembly elections.

Step 4: How much do these legislative assemblies count for in the Lok Sabha? In fact, the Congress does not need to overturn these results in the Lok Sabha elections. Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan, Telangana and Mizoram together have 83 Lok Sabha seats. In the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, the BJP got 65 of these seats; only six went to the Congress. The rest went to the Bharat Rashtra Samithi, Mizo National Front and All India Majlis-E-Ittehadul Muslimeen.

If in the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, the BJP and Congress get exactly the same number of votes in every assembly constituency as they got in the 2023 assembly elections, then the figures will be like this:

- Rajasthan: BJP 14 seats, Congress 11

- Chhattisgarh: BJP 8 seats, Congress 3

- Madhya Pradesh: BJP 25 seats, Congress 4

- Telangana : Congress 9 seats, BJP 0 (BRS gets 7 and AIMIM 1)

- Mizoram: JMP 1 seat.

Overall, according to these assembly elections, out of 83 seats in the Lok Sabha, the BJP gets 46 seats and Congress gets 28 seats. Meaning, instead of gain, according to these assembly results, BJP may suffer a loss of 19 seats while the Congress may gain 22 seats. All the Congress has to do is ensure that the votes it got in the assembly polls, it also gets in the Lok Sabha elections.

Now some may say this is simple mathematics. You haven’t even accounted for “Modi magic”. If Modi’s magic works, then a saffron wave will wash over all these states and the Congress will be wiped out. But if “Modi hai to kuch bhi mumkin hai” – if you believe in magic – then call it faith, what is the need to take cover from the results of assembly elections?

(Yogendra Yadav is a political activist and psephologist, and founder of Swaraj Abhiyan. Courtesy: The Wire.)

Debate: Yogendra Yadav’s Analysis Downplaying BJP Wins in Assembly Polls Is Misleading

Shivasundar

[Note: Yogendra Yadav’s response to this piece is appended below.]

Yogendra Yadav’s intervention through his article and video on The Wire to control the damage from “the psychological warfare” unleashed by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) after the assembly election results are well-intentioned but misleading, both on facts and history.

All of his four arguments to substantiate his claim – that the “BJP’s victory is not so big, and Congress fall is not so deep” – suffer from selective facts and subjective interpretation.

Some of the responses to the election results from the progressive camp are as surprising as the results. Some scholars like Pushparaj Deshpande are calling for self-censorship in publicly criticising Congress over its lacunae and acting as social evangelicals among the traditional vote base of the Congress and providing the last mile connectivity that the Congress lacks.

Others like Yadav are ignoring the political and ideological inefficacy of the Congress as an electoral opposition to the BJP. Both these approaches might provide false comfort to the Congress and the secular camp in the short term, however, they help the onward march of the Hindutva juggernaut. This is why Yadav’s reading of the election results demands close scrutiny. Let us dissect them one by one.

Did the Congress gain 9 lakh more votes, or 50 lakh less than the BJP?

In his bid to boost the morale of the Congress and those opposed to Hindutva politics, Yadav observes that the total number of votes that the Congress polled against the BJP in the four states should bring solace. All the votes the Congress procured in the four states, namely Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Telangana, worked out to be 4.9 crore whereas the BJP got only 4.81 crore. Hence the analysis that despite Congress losing three states, its vote share is higher by 9 lakh than the BJP. Thus, the conclusion is that people still prefer Congress though it lost power.

This is a mathematically correct but politically incorrect conclusion. It is for a simple reason that it includes Telangana in its overall vote calculation along with the three Hindi states. In Telangana, the Congress’s fight was primarily against the Bharat Rasthra Samithi (BRS), not the BJP. The inclusion of Telangana in the overall calculation completely glosses over the dismal performance of Congress in Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, and Madhya Pradesh.

If we exclude Telangana, the number of votes the Congress obtained in the three Hindi states is 3,98,42, 115 while the BJP polled 4,48, 75, 952.

This means the BJP procured 50 lakh votes more than the Congress in these three states. However, if we include Telangana, the picture changes and hence provides false comfort.

If you compare the same with the 2018 elections, the Congress’s predicament becomes more stark. In the previous election, the BJP obtained 3.41 crore votes from these three states and Congress 3.57 crore votes. Thus compared to 2018, the BJP’s tally rose by 1 crore. The Congress could increase its tally by only 47 lakh.

The Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) survey and the earlier Axis survey suggest that most of these new BJP voters happen to be from the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and even Scheduled Tribes (STs). This means the Congress’s social base is eroding, further giving way to the BJP. This is a dangerous portent and would never be acknowledged if one takes comfort in the misleading figure of a 9 lakh vote lead.

Hence, clubbing Telangana with the three heartland states and concluding that the Congress got 9 lakh more votes than the BJP will prevent the former from identifying the steep slide due to its ideological compromise with Hindutva in these states.

Even in Telangana, Yadav seems to be enamoured by the resurgence of the Congress vote share from 28% in the 2018 election to 39.4% in 2023. Though this resurgence is positive for the Congress, it did not deter the double-digit growth rate of the BJP in the state.

This factor should not be missed, because it leads to false comfort that the South has closed its door to the BJP. In Telangana, the BJP procured 6.9% votes and 14.43 lakh votes in the 2018 elections. But in 2023, it doubled to 13.90% with 32.51 lakh votes. It has not only increased its seat share from one to eight but also stood second in more than 18 constituencies where it deployed nefarious tactics of communal polarisation. Thus, the growth rate of the BJP has doubled and its vote share is already a third of the victorious Congress, which is a dangerous portent.

Even in Karnataka, it has a consolidated vote share of 36% in spite of its electoral defeat. One should also not close one’s eyes to the noise it is making in Dravidian Tamil Nadu, and the growing number of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) shakhas in communist Kerala.

Is the vote share of Congress sufficient to stage a comeback?

Another strange logic that Yadav offers is that since the difference in vote share between the BJP and Congress is hardly 2% to 4%, one need not worry much about the loss of power. Since the Congress has reattained a vote share of 40%, it would be easy to stage a comeback.

Again it is a mathematically correct but politically incorrect assessment of Congress’s situation in these three states. All of them are more or less bipolar states, with scarce influence of a third actor. These elections have shown that even the Dalit, Adivasi, and OBC social bases of smaller parties have been encroached upon by the BJP. In such a situation, stagnation of vote share is an indication that it is not only an electoral decline but a political decline.

The analyses of vote shares of the BJP and Congress in the past five elections in these three states, barring Chhattisgarh in 2018, show that the BJP’s vote share is growing whereas the Congress’s vote share is either stagnating or declining with one or two exceptions.

Thus, in Rajasthan, the BJP has an average of 39.88%, with a high of 45.17% in 2013. Whereas the Congress shows an average of 37.14%, with a high of 40.64% in 2018.

In Madhya Pradesh, the BJP’s average is 42.96%, with a high of 48.45% in 2023. The Congress shows an average of 36.42%, with a high of 41.35% in 2018. In Chhattisgarh, the BJP has an average of 40.10%, with a high of 46.27% in 2023.

Overall in bipolar elections, the Congress tends to lose its social base to the BJP, which is obvious in these elections as well.

Thus, even though theoretically a 40% vote share is enough to stage a comeback, the increasing loss of its social base to the BJP makes it impractical. The reason for this lies in the opportunist, Hindutva, and neoliberal politics of the BJP.

Do these results have no impact on 2024?

According to Yadav, in 2003, even though the BJP won in the very same states, it lost the 2004 Lok Sabha, and while it lost these states in 2018, it won the 2019 Lok Sabha polls. Hence one cannot extrapolate these results to have a bearing on the Lok Sabha elections. Again it is a logically correct statement, but a historically and politically problematic conclusion.

After the advent of Hindutva and the communal polarisation of society and its intensification during the Modi regime, the RSS-BJP has cultivated an unchallenged Hindutva appeal among the Hindu electorate cutting across caste, community, class, gender, and region.

The RSS-BJP machinery has been creating false anxiety about the growing threat to the nation and Dharma which could only be thwarted by a virat purush like Modi.

Thus, of late, the elections have not become transactional affairs between the voter and the party, but they are becoming ideological, especially between the BJP voters and the party. Thus, whatever may be the results in the state elections, at least from 2013, the people of these three states, and those in the Hindi belt in general, have overwhelmingly elected the BJP both in 2014 and 2019.

These results will definitely have an impact on the neighbouring Hindi states, which together account for 240 Lok Sabha seats.

It is not ‘Modi magic’ but the colossal political failure of the Congress and the opposition in offering themselves as a credible alternative. Hence ridiculing this sad phenomenon as ‘impossible magic’ is neither a serious analysis nor a serious critique.

Will the BJP lose 19 seats in Lok Sabha if the same pattern repeats in 2024?

According to Yadav, if the same pattern of voting is repeated in Lok Sabha elections, the BJP would lose 19 seats and Congress would gain 22 seats. For such a thing to happen, the Congress should ensure that it repeats the same performance in 2024.

Take for example the 2019 elections. Rajasthan has 25 Lok Sabha seats, Congress got more votes and seats in the 2018 assembly elections, but could not win even one seat there. All 25 went to the National Democratic Alliance (NDA). In Chhattisgarh, where the Congress got 10% more votes than the BJP in the 2018 assembly elections, it could win only two Lok Sabha seats – the BJP got the remaining nine. In Madhya Pradesh, the Congress won only one and the rest 28 were won by the BJP.

Mere extrapolation of votes provides only mathematical solutions.

The history and politics of these states demand introspection and rupture with the past by the Congress to stage a comeback. But, the Congress party has not shown any inclination or a rupture from its soft Hindutva and neoliberal politics either in its campaign or policies.

In this situation, Congress looks like a party with the same fibre as the BJP but with a different colour. Without a radical transformation of Congress politically, ideologically and organisationally, leave alone defeating the BJP, the survival of the Congress itself would become difficult.

Not warning the party and nation about this possibility would be a disservice to both.

I, as a social activist engaged in anti-fascist battles in Karnataka, have always shared Yadav’s dreams respectfully, though not his shifting political strategies. But this analysis took me by surprise and disbelief.

As Gramsci said, “Pessimism of the intellect and optimism of the will” is the need of the hour in these times of gloom.

(Shivasundar is an activist and a freelance journalist based in Bangalore.)

●●

Yogendra Yadav’s response:

I agree with most of the substantive points made by Mr Shivasundar. So there isn’t much of a ‘debate’ between us. If there is a difference in emphasis, it is because he may have missed the whole point of my video (which was translated from Hindi and converted into a write-up).

I was responding to the widespread propaganda that the BJP has drummed up with the help of darbari media: that the hat-trick in the three North Indian states is bound to lead to a hat-trick in the Lok Sabha election, that 2024 is now a closed contest, that the BJP’s victory is inevitable.

All the facts and figures I presented exposed the falsity of this propaganda. My point is that this is not yet a closed contest, that the gap in votes is not impossible to overcome, that if the opposition manages to hold on to the votes that it got even in this defeat this would set the BJP back, that the Lok Sabha election can be different from Vidhan Sabha outcomes. Therefore 2024 is not a done deal yet. I hope Mr Shivasundar doesn’t disagree.

I have nowhere suggested that this is going to be easy, let alone inevitable. Of course, this would require introspection, realignment and hard work on the ground over the next few months. But that is the subject matter of another video.

(Courtesy: The Wire.)

❈ ❈ ❈

Why Congress Lost Chhattisgarh

Arunabh Saikia

The Bharatiya Janata Party is all set to storm back to power in Chhattisgarh, having registered its best-ever electoral performance in the young central Indian state. As of 9 pm on Sunday, the Hindutva party’s vote share (46.3%) was over four percentage points higher than the incumbent Congress (42.2%) in what was largely a bipolar election. In terms of seats, the imminent victory is even more impressive: 54 to the Congress’s 35.

Yet, a closer examination of the mandate – the spatial distribution of seats, for one – and the factors that appear to have shaped it makes one thing fairly clear: the verdict is not so much an endorsement of the BJP as it is a rejection of the Congress government.

Besides, the Congress may have made the job easier for the BJP by employing a cynical brand of politics that undermined the reasons it got voted for five years back.

Adivasi anger

In the 2018 election, the Congress won a whopping 68 seats of the 90 seats in the Chhattisgarh assembly.

Five years later, it has lost ground across the state. The most heavy losses, though, have come in the state’s Adivasi belts – areas it has traditionally been strong in and which it swept last time.

In the northern part of the state, in the mineral-rich Surguja region, the party has been wiped out. In 2018, it won all 14 seats in this Adivasi-majority area.

It fared better in Bastar, the other Adivasi belt, in the south of the state – but only marginally. It won four of the 12 seats here – in 2018, it emerged on top in all of them, save one.

Scroll’s reporting from these areas noted the disaffection among Adivasi residents: many accused the Congress government of reneging on its promises. Among the biggest sources of disaffection was what people called the “half-hearted” implementation of the Panchayat Extension to Scheduled Areas Act that give a degree of autonomy to village councils in Adivasi areas.

The Congress had come to power promising Adivasis more control over their land and forest resources but had ended up prioritising corporate interests, people in these areas complained.

Christian vote

Then, there was widespread disappointment among Adivasis who followed Christianity about the Congress government’s failure to prevent attacks on them by vigilante groups. Still, others from the community blamed the police under the Congress for overt alacrity in taking action based on complaints of conversion by Hindutva outfits.

In North Chhatisgarh’s Jashpur, for instance, a district with a large Adivasi Christian population, many people Scroll interviewed weeks before the election spoke about the arrest of a nun earlier in the year – an action that they said was unjust.

The Congress looks set to lose all three seats in the district.

A gambit backfires

Even as the Congress government shied away from speaking up for the minority Christians, it built temples, developed Hindu tourism pilgrimage circuits, and spent hundreds of crores on buying cow dung as part of a programme to promote cow rearing and cow protection.

Chief Minister Bhupesh Baghel, who would often proudly wear his Hindu identity, seemed to believe such things would hold him in good stead among Hindu voters.

Except that he may have walked straight into the BJP’s trap.

Critics say Baghel’s “soft Hindutva” laid the ground for the saffron party to deploy religious polarisation as an electoral issue in the state with very little history of communal politics.

An election like no other

To be sure, there is an unmistakable imprint of religious polarisation – unprecedented for the state – on Sunday’s verdict.

Consider Bemetara in central Chhattisgarh. In 2018, the Congress had won all three seats in the district.

Earlier this year, the district saw communal violence between Hindus and Muslims, which left three people dead: two Muslims and one Hindu. While the state government announced compensation for the Hindu victim’s family, Baghel maintained a studied silence on the slain Muslims.

That, however, did not stop the BJP from bringing up the incident in the run-up to the polls this year. Not only did the party project the Hindu victim’s father as its candidate for one of the seats in the district, Union minister Amit Shah at an election meeting said the area had become the “hub of love jihad”.

“Love jihad” is a Hindutva conspiracy theory – widely debunked – that Muslim men lure Hindu women into romantic relationships with the covert intention of converting them to Islam.

The BJP swept all three seats in the district this time.

In neighbouring Kawardha, the state’s lone incumbent Muslim MLA, Mohammad Akbar, lost to a person accused in the Bemetara riots.

One-trick pony

These losses are significant for more reasons than one. They exemplify how the BJP managed to blunt the Congress’s trump card this election season in the plains of Chhattisgarh: generous paddy procurement rates.

The Congress went into this election almost entirely on the basis of its successful paddy bonus disbursal scheme in the last five years. If elected to power, it said it would do even better.

But the BJP, which suffered in 2018, because of not being able to deliver a similar bonus it had promised, also promised to make amends on that front.

While there was some scepticism among farmers to believe the BJP given its track record, it appears many in the districts of Kawardha-Bemetara-Durg area decided to repose trust in it since it was presented as a “Modi guarantee”.

These losses sealed the fate of the Congress. Already weighed down by widespread Adivasi discontent, the party’s only chance at retaining power came from the rice-growing plain areas. But the BJP beat the Congress at its own game here.

(Courtesy: Scroll.in.)