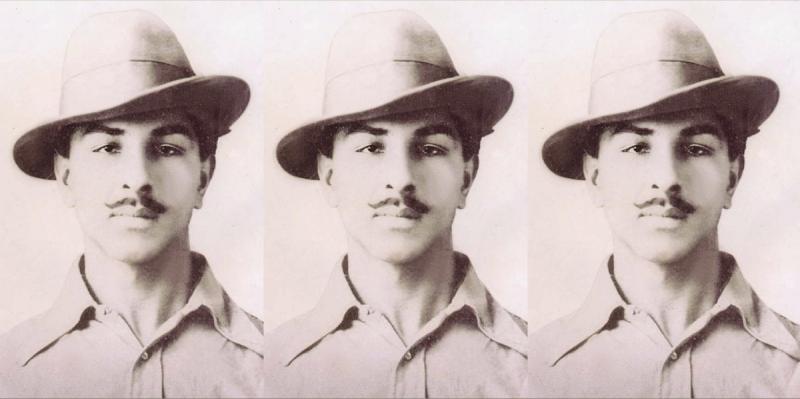

28 September 2020: Bhagat Singh was born on this day in 1907, in a village called Banga, now in Pakistan. The village, like it does every year, is planning to celebrate his birthday with pride. Bhagat Singh’s birth turned this remote dusty village into a place of pilgrimage. It has been declared as a national heritage site by the Pakistani government. Bhagat Singh evokes respect among many across the border, despite the two countries’ bitter relationship, because he always vouched for human dignity and rights beyond sectarian divide. He castigated all those who floundered on these basic values, as is evident from the fairly huge corpus of writings he bequeathed to us.

How was a young man, who did not live beyond his early twenties, able to think and write so profoundly about the complex social, philosophical, economic and political issues? One simple answer to this question is that he was a voracious reader, he read anything that helped him to unravel the complexities of life from both prose and poetry. All his comrades reported in their memoirs that they never saw Bhagat Singh without a book in his hand and a few in his pockets. Even his mother reprimanded him for pushing books into his jacket pockets, which were mostly torn. He was also passionate about some meaningful as well as romantic films. He learnt a lot from the plays he participated in as a young man.

Not just a raw nationalist

When one talks about Bhagat Singh as a thinking individual and not just as a raw nationalist, it does not mean that he was a scholar in his teens. It only emphasizes his exposure to world literature through intense reading in his short life. It is also an attempt to wean him away from the image of a trigger-happy young man. This image was deliberately publicised by the colonial government, which many of us internalised and continue to romanticise every day. We know he had a very short life, most of which was spent under the surveillance of the colonial government. Yet, he could pursue his passion for reading and writing relentlessly.

Not much was known about him in the 1930s except for his martyrdom. Most of Bhagat Singh’s commendable traits were unravelled by the family, friends and researchers many decades later. His extraordinary hunger for reading was properly documented when he was arrested and imprisoned after the assembly bomb explosion. However, Ajoy Ghosh, one of his associates, wrote about his first impression of him in 1923, when he found him a shabbily clad and a simple village lad lacking smartness and self-confidence. Within five years in 1928, he was transformed and when asked about the change, he responded with one word: ‘Study’. In his own words: “Study was the cry that reverberated in the corridors of my mind. Study to enable yourself to face the arguments advanced by opposition. Study to arm yourself with arguments in favour of your cult.”

Before the assembly bomb explosion in April 1929, the revolutionaries stayed at Agra for some time and set up a small office at Hing ki mandi. Bhagat Singh soon established a small library, comprising 175 books by around 70 authors, most of them collected from his friends and supporters. Though small, the library was rich in literature, mainly comprising books on economics. There were also books on the trade union movement, explosives and bomb-making and a few about the Russian revolutionaries. These books are still lying in a state of neglect at Maalkhana Record in a lower trial court of Lahore.

Intellectual life began after his arrest

Bhagat Singh’s intellectual life really began after his arrest, though he was already an avid reader. Shiv Verma, one of his close comrades in jail, wrote about Singh’s love for books thus:

“We had easy access to books in the jail since the day one and the atmosphere was quite congenial for study and exchange of ideas…but Bhagat Singh’s arrival made this much more lively…Though we all had a passion for reading, but Bhagat Singh was a class by himself. Despite his soft corner for socialism, he was passionate about fiction as well, particularly with political and economic themes. Dickens, Upton Sinclair, Hall Cane, Victor Hugo, Gorky and Oscar Wilde were among his favourites.”

While in prison, Bhagat Singh and his comrades went on a long hunger strike raising several demands of the political prisoners. Two of those demands are relevant here:

- All books, except those proscribed, with writing material, should be made available without restriction.

- At least one daily paper should be supplied to each political prisoner

Bhagat Singh was almost certain that he would be executed, yet he wanted to read as much as he could and wanted his comrades to read as well. He could leave behind a huge corpus of written legacy only because his choice of reading material was diverse.

How did he manage to get all this literature, most of which was suspect in the eyes of the colonial administration? There were two main resources for books. One of them was the Dwarka Das Library, established by Lala Lajpat Rai in Lahore and the other was a bookshop called Ramkrishna and sons. This bookshop had resources to procure banned books from England. Both of them were the main suppliers of Marxist and revolutionary literature. Rajaram Shastri, the young socialist librarian of the library once told Shiv Verma that Bhagat Singh did not just read books, he almost devoured them, yet his yearning to seek knowledge always remained unsatiated.

Over the years, it has been established now that Bhagat Singh was an avid reader. His friend Jaidev Gupta used to supply the specific books he needed in jail. He also recalled that in his late teens, Bhagat Singh ‘was always seen with a book in English in his hands and a dictionary in his pocket.’ Yashpal, a well-known writer and Bhagat Singh’s associate, saw him driving a camel-drawn cart of his father as ‘an interesting sight: the camel drove the cart and Bhagat Singh sat in the driver’s seat, reading his book.’ He also read Bankim’s Anandamath and Savarkar’s book on 1857. Bhagwan Das Mahor recollects that Bhagat Singh had given him a copy of Marx’s Das Kapital and thus planted the first seed of socialism in his heart. Unfortunately, this is something not safe or even wise to confess in public today.

I will conclude with the last moments of Bhagat Singh’s life, as reported by his close associate Manmathnath Gupta, he writes:

“When called upon to mount the scaffold, Bhagat Singh was reading a book by Lenin or on Lenin. He continued his reading and said, ‘Wait a while. A revolutionary is talking to another revolutionary’. Bhagat Singh continued to read. After a few moments, he flung the book towards the ceiling and said, ‘Let us go’.” [Emphasis added]

This is the true legacy of Bhagat Singh which we need to commemorate. He read all possible revolutionary or even anarchic literature to build his vision of independent India. It also tells us why we need to listen to those who read and write; they may imagine India differently, but they do not deserve to be punished for what they read or write.

(S. Irfan Habib served as Maulana Azad Chair at the National University of Educational Planning and Administration, New Delhi. Article courtesy: The Wire.)