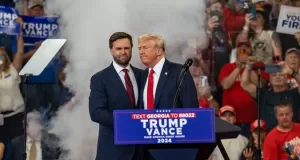

Within days of his return to office, President Donald Trump unleashed a chilling display of authoritarianism, providing a stark reminder of the specter haunting the United States: the specter of fascism. As reported in the New York Times, his actions underscored a vision of governance steeped in cruelty and unchecked power. With the stroke of a pen, Trump pardoned 1,500 individuals involved in the January 6th insurrection, dismantled environmental protections, opened Alaska’s wilderness to expanded oil and gas drilling, terminated Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) programs across federal agencies, and signed an executive order ending birthright citizenship. He erased recognition of gender diversity on official documents, escalated attacks on transgender Americans, withdrew the U.S. from the Paris Climate Agreement and the World Health Organization, declared a national emergency at the southern border, dispatched thousands of troops, and initiated mass deportation orders targeting immigrants. Each action exemplified not only the brutalities of gangster capitalism but also a profound disregard for human rights, social justice, and the preservation of the public good.

What makes these assaults even more alarming is their widespread support. Trump’s war on civil rights, immigrants, the rule of law, the environment, and gender equity is endorsed by the MAGA Party, a significant portion of the American public, billionaires seeking deregulation, and a chorus of complicit pundits and politicians. This is more than a moral collapse or a democracy on life support—it reflects the deliberate cultivation of civic ignorance and the institutional erosion that allowed fascism’s seeds to take root, with Trump’s presidency representing its most visible end point.

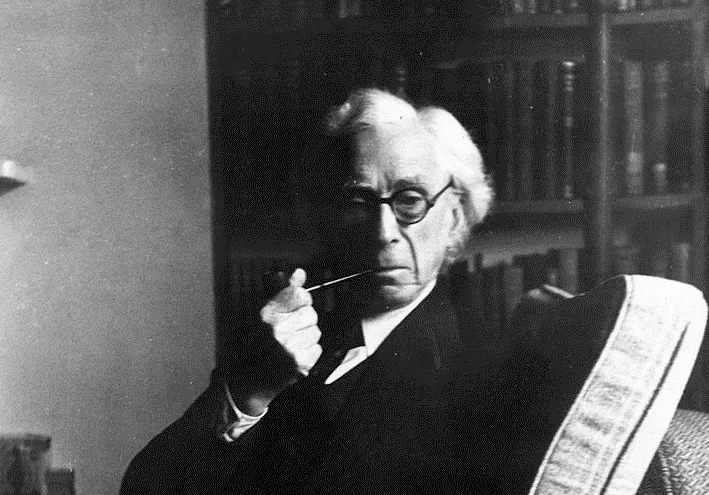

At the core of this culture of gangster capitalism lies an interconnected web of anti-public intellectuals, media personalities, cultural influencers, and powerful apparatuses—including the legacy press and online platforms—that actively promote or tacitly enable an authoritarian agenda. Their complicity contrasts sharply with historical figures who resisted tyranny with unflinching courage. Bertrand Russell, for instance, serves as a reminder of intellectual bravery in dark times. Today, such moral clarity is rare but not extinct. Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde, who led the National Prayer Service at Washington National Cathedral, embodies a bold and energized resistance, challenging the silence and submission that so often accompany the rise of authoritarianism.

During the service, Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde addressed President Trump directly, urging him to embrace justice, compassion, and care in his policies, particularly toward immigrants and those most vulnerable under his administration. With a solemn yet hopeful tone, she declared:

“Millions have placed their trust in you. As you said yesterday, you have felt the providential hand of a loving God. In the name of that God, I implore you: have mercy on the people of this nation who now live in fear. There are gay, lesbian, and transgender children in families across the political spectrum—Democrat, Republican, and Independent—some who fear for their very lives. Have mercy upon them.”

As her sermon neared its conclusion, she continued, her words both a plea and a moral indictment:

“I ask you, Mr. President, to have mercy on the children who fear that their parents will be taken away. I ask you to extend compassion and welcome to those fleeing war zones and persecution, seeking refuge on our shores. Our God commands us to be merciful to the stranger, for we too were once strangers in this land.”

Trump’s response was as predictable as it was venomous. He dismissed the service as “boring and uninspiring,” deriding Budde as a “radical left hardline Trump hater.” His words, steeped in scorn and his trademark disdain for critique, encapsulated the spirit of his administration—a politics of division, cruelty, and vindictiveness.

This spirit found an echo in Republican U.S. Representative Mike Collins of Georgia, who weaponized Budde’s sermon on social media. Posting a video clip of her heartfelt appeal, he coldly remarked: “The person giving this sermon should be added to the deportation list.”

In these exchanges, the chasm between Budde’s call for mercy and Trump’s politics of malice became starkly evident—a collision of two opposing visions for the nation. One rooted in compassion, the other in the unrelenting embrace of cruelty.

The spirit, boldness, and courage embodied in Budde’s speech echo a long and vital history of resistance. Under every regime of domination, there have always been voices that refuse to be silenced—public intellectuals and everyday citizens who, together, stand against the tides of bigotry, hatred, war, and state violence. These voices remind us that even in the darkest times, resistance is not only possible but necessary.

One such voice, whose life and work illuminate the enduring power of civic courage, moral responsibility, and the willingness to risk everything for justice, equality, and freedom, is Bertrand Russell. His legacy offers us profound lessons for navigating our current moment, where the stakes of resistance feel as urgent as ever. My connection to Russell’s work feels especially personal, as my own writings are housed in McMaster University’s Mills Library, alongside a significant archive of Russell’s papers. In reflecting on his life, we are reminded that the struggle for justice is a continuum—one that demands not only bold ideas but also the bravery to act upon them.

One of the most unexpected and meaningful moments of my personal and scholarly life was standing beside a towering image of Bertrand Russell during the ceremony marking the donation of my personal archives to McMaster University Library’s William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections. It felt like a quiet dialogue across time—a convergence of lives committed to ideas, justice, and the unyielding pursuit of truth. Libraries and archives hold a special kind of magic, especially in an age when historical memory is eroded by an avalanche of information, the unceasing churn of emotional overload, and a culture entrapped by what Byung-Chul Han calls “the immediate presence.”

In stark contrast to this frenzy of hyper-communication and ephemeral data, the archive stands as a sanctuary for depth and reflection. It safeguards not just the fragments of the past but the larger arc of its story, providing a sense of wholeness and continuity. Here, time stretches beyond the fleeting moment, offering a context that embraces the works, personal artifacts, and relationships that shape the lives of artists, intellectuals, and cultural workers. The archive resists the tyranny of the present, reminding us that the threads of history weave a fabric far richer and more enduring than the fleeting snapshots and soundbites of our digital age.

Having my work archived along with Russell’s was particularly moving since he was a model for me as a public intellectual as I began teaching and writing in the 1960s. I came of age when intellectual, political, and cultural paradigms were shifting. Protests were advancing on university campuses and in the streets against the Vietnam War, systemic racism, the military-industrial complex, the corporatization of the university, and the ongoing assaults waged on women, the poor, and the vulnerable. Intellectuals and artists such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Allen Ginsberg, Norman Mailer, Ellen Willis, Susan Sontag, Paul Goodman, James Baldwin, Angela Davis, and Martin Luther King, Jr. were translating their ideas into actions and exhibiting a moral courage that both held power accountable and refused to be seduced by it. This was an age of visionary change, civic courage, and democratic inclusiveness; it was a time in which language translated into actions that enabled people to understand how power operated on their daily lives and how their daily existences and relationships to the world could be more engaging in critical and radically imaginative ways.

For me, Bertrand Russell stood out among these intellectuals in a way that was both iconic and personal. Russell was not only a rigorous scholar but also a public intellectual who moved with astonishing ease through a range of disciplines, ideas, and social problems. He embodied a new kind of public intellectual, one who functioned as a border crosser and traveler who, like another great public intellectual, Edward Said, refused to hold on to scholarly territory or a disciplinary realm in order to protect or bolster his fame or ego. Careerism was anathema to Russell and it was obvious in his willingness to push against conceits and transgressions of power—whether it was contesting World War I as a conscientious objector, dissenting against the authoritarian populism consuming much of Europe in the 1930s, protesting against the threat of nuclear weapons, or criticizing the horrors and political depravity that marked the United States’ war against the Vietnamese people.

In pushing the boundaries of civic courage and the moral imagination, Russell took risks, put his body on the line, and made visible the crimes of his time, even if it meant going to jail, which he did as late in his life as the age of 89 after protesting against nuclear weapons. Russell lived in what can be called dangerous times and he responded by placing morality, critical analysis, collective struggle, and a profound belief in democratic socialism at the center of his politics.

I was always moved by his courage, and his belief in the political capacities of everyday people and the notion that education was central to politics itself. Russell believed that people had to be informed in order to act in the name of justice. He believed that politics could be measured by how much it improved people’s lives, gave them a sense of hope, and pointed to a future that was decidedly better than the present. Russell, like Václav Havel, another towering public intellectual, believed that politics followed culture and that there was no possibility of social change unless there was a change in people’s attitudes, consciousness, and how they live their lives. Russell believed that a critical education could teach young people not to look away and to take risks in the name of a future of hope and possibility. Russell’s radical investment in the power of education was more than simply a strong conviction. Not only did he start his own progressive school in the 1920s, but he believed that one demand of the public intellectual was to be rigorous and accessible and to make one’s work meaningful in order for it to be critical and transformative. Russell connected education to social change and believed that matters of identity, desire, power, and values were never removed from political struggles.

Not only did he write incessantly as a public intellectual, but he was always willing to throw his body and mind into the thick and fray of the social problems he addressed. As a writer and political activist, he was overtly derided and even condemned by other intellectuals. One episode that moved me immensely when I learned of it was that he was denied a position at the College of the City of New York. At the time, powerful conservatives both in and out of the Catholic Church saw his ideas as dangerous, going so far as to claim if he took up the job at CCNY, he would be occupying a “Chair of Indecency.” I read about this period in Russell’s life soon after I was denied tenure for political reasons at Boston University by the notorious right-wing president, John Silber.

Russell’s willingness to keep going in the face of such attacks nurtured in me both energy and faith in my convictions. As a radical educator, Russell inspired me and gave me the courage to address issues animated by a fierce sense of justice and the political and moral imperative to fight against “the texture of social oppression and the harm that it does.” Like Russell, I learned that thinking can be dangerous and that it demands a certain daring of mind and willingness to intervene in the world. Russell convinced me that to be an educator, you had to be willing to cause trouble in times of war and upheaval and just as willing to disturb the peace in moments of quiet acquiescence. At a time when public intellectuals seem to be in retreat, Russell’s legacy and work are even more important given the darkness now engulfing much of the globe.

Russell is more important to me today than he was when I first read his works in the 1960s. He is a reminder of a type of engaged intellectual that crossed boundaries far removed from the university with its sometimes deadly specialisms, corporatism, conformism, and separation from the problems of the day. While public intellectuals still exist today, too many of them speak from narrow specializations, narrate themselves in soundbites appropriate for the digital age, and often refrain from speaking to the broad audiences and tangled issues of the day. Too many of them advocate for single issues and lack the knowledge or willingness to speak in terms that are comprehensive, willing to do the hard work of connecting a vast array of issues and common concerns. Russell’s claim that his three passions were “the longing for love, the search for knowledge, and unbearable pity for the suffering of mankind” seem quaint in today’s fast-paced culture of consumerism, unchecked individualism, and a crippling obsession with self-interest.

Russell is a crucial reminder of the value of historical consciousness and memory because his life, writing, actions, and moral courage remind us of the work that public intellectuals can do and how they can make a difference. Russell provides a model of what it means to talk back, scorn easy popularity, and refuse to wallow in the discourse of comfortable platitudes. Russell was not merely a witness and, like Martin Luther King, Jr. and other notable figures of his generation, refused to keep silent and was equally appalled by the “silence of good people.” He made clear that there had to be a crucial element of love and solidarity in the ability to feel passionate about freedom and justice. Erich Fromm, one of the great Frankfurt School theorists, called Russell a prophet because his “capacity to disobey is rooted, not in some abstract principle, but in the most real experience there is—in the love of life.” In an age of “fake news,” emergent fascism, systemic racism, and engineered destruction of the planet, militarism, and genocide, Russell is an extraordinary and insightful reminder of the power of informed rationality, critical education, and evidence. At a time when the threat of a nuclear disaster looms larger than ever, Russell offers both in words and deeds the recognition that security cannot be gained through a culture of fear, fraud, armaments, and armed struggle.

At a time when democracy teeters under siege, authoritarian populism surges, public values are eroded, and trust in democratic institutions falters, Bertrand Russell’s writings, actions, and struggles offer an enduring reminder of what is necessary to confront the present darkness. He calls us to civic courage, moral outrage, and the critical thinking required to bridge private troubles with broader social transformations. His life and work stand as a testament to the unyielding pursuit of justice and the recognition that no society, no matter how idealized, is ever just enough.

For Russell, politics was not just about economic structures; it was a battle for the meaning and dignity of humanity itself —over agency, identity, values, and the ways we see ourselves in relation to others. These concerns resonate profoundly today, as unbridled individualism, the fetishization of privatization, and a narrow devotion to self-interest have been elevated to virtues in many Western societies. These forces have paved the way for a moral void, a nihilism that fuels the resurgence of authoritarianism across the globe. Against this collapse into despair, Russell’s vision remains a vital antidote—expansive, hopeful, and profoundly life-affirming.

Russell’s legacy is not just a lesson in intellectual brilliance or political acumen, but in the audacity of hope paired with the courage to act. He reminds us that history bends not by passive observation, but by collective struggles, solidarity, and the refusal to accept injustice as inevitable. To remember Russell is to embrace a moral clarity that resists indifference and cynicism, and to imagine a world where dignity, equity, and joy are not luxuries but foundational principles.

Standing beside his archives was, for me, an extraordinary honor. It was not merely an encounter with history but an invitation to carry forward the weight of its lessons. In that moment, I felt the enduring shadow of a life devoted to justice and civic responsibility, a shadow that challenges us to live with greater purpose.

To remember Russell is to remember the indispensable role of hope in the face of despair, the necessity of resistance when the specter of fascism is with us once again, and the moral obligation to imagine and fight for a world yet to be born. His legacy is a call to action—a reminder that even in the darkest of times, the power of ideas, the courage of individuals, and the collective force of mass movements can light the way forward.

(Henry A. Giroux currently holds the McMaster University Chair for Scholarship in the Public Interest in the English and Cultural Studies Department and is the Paulo Freire Distinguished Scholar in Critical Pedagogy. His most recent books include: The Terror of the Unforeseen (Los Angeles Review of books, 2019), On Critical Pedagogy, 2nd edition (Bloomsbury, 2020); Race, Politics, and Pandemic Pedagogy: Education in a Time of Crisis (Bloomsbury 2021); Pedagogy of Resistance: Against Manufactured Ignorance (Bloomsbury 2022) and Insurrections: Education in the Age of Counter-Revolutionary Politics (Bloomsbury, 2023), and coauthored with Anthony DiMaggio, Fascism on Trial: Education and the Possibility of Democracy (Bloomsbury, 2025). Giroux is also a member of Truthout’s board of directors. Courtesy: CounterPunch, an online magazine based in the United States that covers politics in a manner its editors describe as “muckraking with a radical attitude”. It is edited by Jeffrey St. Clair and Joshua Frank.)