The prospect of Australia joining a war between the United States and China is truly terrifying. Such a war could cost millions of lives and even escalate into nuclear conflict. But this is precisely the path the Australian ruling class is preparing to go down.

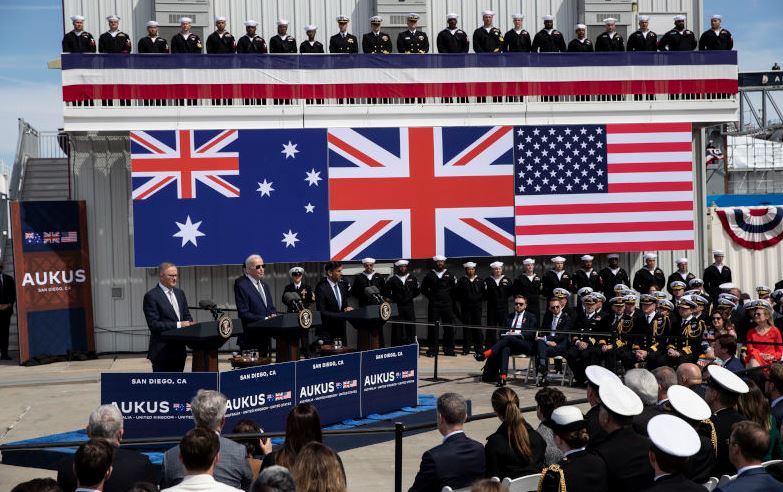

The most obvious sign of their intention is the acquisition of nuclear-powered attack submarines via the AUKUS military pact with the United States and the United Kingdom. That is in addition to the hundreds of billions of dollars successive governments, both Labor and Liberal, had already committed to military spending in coming years.

Efforts to drum up popular support for war are intensifying. In March, the Age and the Sydney Morning Herald ran a series of articles headed “Red Alert”, warning that Australians must prepare for war within two or three years. “Most important of all is a psychological shift”, they declared. “Urgency must replace complacency. The recent decades of tranquillity were not the norm in human affairs, but an aberration. Australia’s holiday from history is over.”

Hardly a week goes by now without the mainstream media breathlessly reporting on the threat from Chinese spies, or recounting the latest manoeuvres of rival navies and air forces in the South China Sea or the Taiwan Strait. Harking back to the racist paranoia of the Cold War, China is portrayed as an existential threat to people living in Australia.

But outside of Australia’s military alliance with the US, China has no motivation to attack Australian territory, let alone the capacity to invade this continent. The risk of a Chinese attack arises only because Australia serves as a base for US military forces and because Australia’s own military might join a wider conflict.

It is true that China is challenging US hegemony in East Asia, the world’s most dynamic centre of capital accumulation. This conflict is the latest manifestation of what Marxists call “imperialism”, in which nation-states compete to protect the long-term economic and strategic interests of “their” capitalist class.

The Australian state is an aggressive and active participant in this never-ending contest, using its substantial power to defend the specific interests of the Australian ruling class. Australia is the thirteenth largest economy in the world, allowing it to field the strongest military in South-East Asia.

As a mid-ranking power, however, Australia has always sought to bolster its position through alliances with “great and powerful friends”, first Britain, then the United States. Critics of the US alliance often argue that it undermines Australian sovereignty or demonstrates a national inferiority complex. This ignores the benefits for Australian capitalists of friendship with the world’s most powerful state.

The alliance means that Australia can purchase the latest high-tech weapons, including nuclear submarines. It allows Australia to piggyback on US intelligence networks and diplomatic efforts. And ultimately it provides an “insurance policy” against attack by other major powers. This has saved Australia the substantial cost of building its own nuclear weapons.

Australian capital has therefore supported US dominance in Asia since World War Two, not out of subservience, but to boost its own standing. The Vietnam war is a good example. The Menzies government encouraged the US to commit to all-out war in Vietnam because it feared that the United States might retreat in the face of communist insurgencies, leaving Australia isolated.

In an attempt to stiffen US resolve, Australia offered to contribute troops long before any request came from Washington. Australia also opposed early negotiations to end the war. A bigger war that further committed the US was what was wanted, not peace. Far from being forced into the war against its own interests, Australia was straining at the leash, hoping to drag the US along behind.

Similarly, today there is near consensus among the ruling class and its hangers-on that Australia must help defend the regional order established through the USA’s victory over Japan in the Second World War. Those who argue that some kind of accommodation should be reached with China or that the US alliance should be deprioritised are completely marginalised within mainstream debates.

But what of Australia’s economic relationship with China? For years, China’s surging economic development has been a goldmine for Australian capitalism, boosting exports in coal, iron ore, international education and more. China accounted for 36 percent of all Australian exports in 2021, far more than any other country. In a world in which cold hard cash normally reigns supreme, and with the global economy teetering on the edge of recession, why risk such an important market?

One factor is access to foreign capital markets, which are also important for Australian corporations. US investments in Australia exceeded $1 trillion in 2021; China, including Hong Kong, was around one-fifth of that.

But that aside, the liberal idea that trade is straightforwardly mutually beneficial, and that trading partners become friends, is wrong. Trade is also antagonistic, with each side trying to cut the best deal possible.

This is why Australia constantly goes on about maintaining an international order that is “open” and “rules-based”. For decades, US military and financial supremacy in East Asia has underpinned a basically liberal economic order, with trade structured around an open market. This has been highly beneficial to Australia, because it is an efficient, capital-intensive producer.

But what if China was able to impose a trade regime are based on military or political strength, structured through trade blocs or exclusive economic zones? What if China could dictate rules around capital flows, or the conditions under which Australia interacted with other important regional economies?

Australian capitalists, not surprisingly, prefer the existing system in which the US guarantees security, and they concentrate on making profits. Sadly for them, those good times are over. The recently released Defence Strategic Review laments: “No longer is our Alliance partner, the United States, the unipolar leader of the Indo-Pacific. Intense China-United States competition is the defining feature of our region and our time.”

In this contest, Australia is not merely the USA’s strongest supporter. It is adopting an increasingly aggressive posture, and fuelling tensions.

In addition to providing nuclear submarines to Australia, the AUKUS pact involves the development of advanced weapons such as hypersonic missiles and closer integration of naval forces to confront China. Australia has backed the US over its “freedom of navigation” operations in the South China Sea. And, ultimately, the Australian government is preparing to join the US in a war with China over Taiwan.

Diplomatically, Australia has attacked China’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Hong Kong democracy movement. There are constant claims of Chinese cyber-attacks, military provocations or “interference” in Australian politics. And Australia was the first country to ban Chinese tech company Huawei from building a 5G phone network.

Tensions between Australia and China have eased somewhat since the last election. Labor politicians are less given to inflammatory rhetoric than the Liberals. But on the fundamentals of advancing Australian imperialism, they are indistinguishable.

First, this means forging ever closer military ties with the USA. This is not limited to AUKUS. Northern Australia is now routinely used as a base for the US marines and air force, and Tindal air force base near Darwin is being expanded to host nuclear-capable B-52 bombers. US spy and communications bases at Pine Gap and North West Cape would play a vital role in any conflict with China.

Second, Australia is significantly boosting its own military capability. This includes buying the latest jet fighters, long-range missiles, surveillance systems and satellites, drones, cyber warfare capabilities, and more transport ships to move troops around the region. Then there are the new submarines. Only six countries in the world currently operate these kinds of nuclear attack submarines, including China with a fleet of six. They are some of the most advanced weapons systems in existence and will substantially enhance the power of Australia’s navy.

None of this comes cheap. Nuclear submarines alone have been costed at up to $368 billion. Under the Coalition, annual defence expenditure was already set to rise to $74 billion by 2029-30, up from $42 billion in 2020-21. Labor has now pledged to increase spending even further, without specifying by how much.

But this military build-up isn’t about protecting the Australian mainland. The whole point of nuclear submarines and cruise missiles is to take the fight to China, potentially thousands of kilometres from Australian shores. The 2020 Defence Strategic Update document made clear the enormous extent of Australia’s ambitions:

“Defence planning will focus on Australia’s immediate region: ranging from the north-eastern Indian Ocean, through maritime and mainland South East Asia to Papua New Guinea and the South West Pacific. That immediate region is Australia’s area of most direct strategic interest … Access through it is critical for Australia’s security and trade.”

Australia’s geographic isolation from its main strategic and economic partners leaves it reliant on long maritime trade routes and military lines of communication. Hence a continued obsession that the surrounding islands, from the Indonesian archipelago through to the south-west Pacific, must be controlled either by Australia directly or by friendly powers. It is a region in which Australia plays second fiddle to no-one, including the United States.

Australia supported Britain acquiring colonies in the region as part of the global scramble for colonies in the late nineteenth century, and then took over running PNG and Nauru, including capturing territory from Germany in World War One. The Second World War was in large part fought to defend these possessions from Japan.

A new phase of Australian neo-colonialism in the Pacific began with Australia’s military intervention in East Timor in 1999. This ensured that East Timor’s transition to independence did not result in a chronically unstable state on Australia’s doorstep.

There followed a string of interventions into Pacific island nations that were seen as “failed states”, characterised by mismanagement, corruption and lawlessness. This has included military and police deployments as well as Australian civilian personnel being implanted within local governments. Today, a substantial Australian presence continues in PNG, Nauru and the Solomon Islands.

But with China increasingly active in the region, maintaining Australia’s dominant position is getting harder. It’s been a priority for Labor since coming to office. The ALP is critical of the Liberals for supposedly having ignored the Pacific except as a source of cheap labour, and for allowing China to gain ground.

Foreign Minister Penny Wong has launched a diplomatic charm offensive, talking up her supposed “profound sense of kinship with the Pacific” and spruiking Labor’s credentials on climate change. By acknowledging that climate change actually exists and pledging to cut domestic carbon emissions, Labor can pretend that it is doing something about the existential threat for many Pacific island nations. It’s greenwashing on a grand scale: Labor is doing precisely nothing about the fact that Australia is one of the world’s largest fossil fuel exporters.

For its part, China can bring its sheer economic weight to bear, challenging Australia’s primacy in the region as both a trade partner and source of investment funds. In 2018, Australia was forced to fund construction of a new undersea internet connection between PNG, Australia and the Solomon Islands, forcing out Chinese communications company Huawei. In 2022 the Australian government provided the bulk of the finance for Telstra’s hasty $2.4 billion purchase of regional phone company Digicel Pacific, again rushing to act before a Chinese company could complete the deal.

China is now also the second biggest aid donor in the Pacific, although remaining well behind Australia. Both China and Australia assume that whoever underwrites aid projects will gain influence over local governments, and they are jostling for position in key countries. For example, Australia rushed to provide the PNG government with emergency loans worth hundreds of millions of dollars during the COVID pandemic, prompted by fears that China was about to offer its own loans.

China is also seeking security ties with several Pacific nations. The worst-case scenario for the Australian ruling class is that China establishes a permanent military presence in the region. Suggestions that China might build a fishing port on the Papua New Guinean island of Daru in the Torres Straight caused panic in 2020.

The Solomon Islands have been the recent focus of competition. In 2021, anti-government riots broke out in the capital, Honiara, partly in response to the government shifting diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China. Australia rushed to deploy military and police personnel under a pre-existing security assistance treaty.

But China subsequently signed a similar security treaty with the Solomons Islands government, paving the way for its own deployments in the future. Beijing began providing training and weapons to local police. The response in Canberra was panic and outrage that China would dare impinge on Australia’s exclusive domain.

The Australian ruling-class response is to get in first. Its soldiers are permanently embedded with the PNG defence force, and an even stronger presence can be expected as a result of a new security treaty currently under negotiation. Australia is already redeveloping the Lombrum Naval Base on Manus Island, off the north coast of New Guinea. Originally built during World War Two to fight Japan, it will now help Australia and the US confront China.

For the Australian ruling class, this competition with China is vital to maintaining power and profits. But for the bulk of people living in Australia, there is nothing to gain and everything to lose. The living standards of workers, students and the poor are being shredded as hundreds of billions of dollars are wasted on weapons of destruction. It is the lives of ordinary people that will be sacrificed in any actual war with China, not those of the politicians, generals and billionaire mining magnates.

We need to build an anti-war movement that stands resolutely against the drive to war. We must demand an end to Australia’s military build-up, starting with cancelling the nuclear submarines and AUKUS. Our society’s wealth must be devoted to health, housing and education, not to building weapons of aggression and mass destruction. Aid in the Pacific must be directed to relief of poverty and combating the effects of climate change, not defending capitalist strategic priorities and building military bases.

The US alliance must be scrapped entirely. In no way does it make people in Australia safer; it only increases the likelihood of conflict with China. US military and spy bases in Australia must be closed immediately. Joint training exercises between Australia and the US must cease. Australia should also demand that US forces withdraw from Japan, South Korea and the rest of Asia, removing the string of bases that encircle and threaten China.

Above all, we must reject the logic that we have to take sides in the great power conflict between the United States and China. That is a false choice which means our side, the international working class, loses either way.

(Courtesy: The Red Flag. Red Flag is a publication of Socialist Alternative, an Australian socialist group.)