Bharat S. Tiwari

The very idea of a festival marking the onset of spring is uplifting, but when it also brings with it the fragrance of a syncretic culture, it becomes incomparable. Such is the annual celebration of Basant Panchami at the dargah, in Delhi, of Sufi saint Nizamuddin Auliya (1238–1325 C.E), of the Chishti order.

The festival was celebrated on January 29 this year.

The fact that the festivities take place in Nizamuddin, which is among the oldest, continually habited areas of the city, is a reminder that Delhi is not just about realpolitik; it is equally about cultural syncretism and the saint’s powerful message of love and religious harmony among communities—with Nizamuddin Auliya’s most well-known disciple, Amir Khusrau, epitomising the efflorescence of that universe.

Khusrau was part of the royal court of seven rulers of what is known as the Delhi Sultanate, but it is the worldview the mystic poet–musician and scholar expressed through the abundant literary and musical landscape he created, that we remember to this day. It shaped the cultural ethos of the subcontinent in indelible ways.

He wrote prolifically in Persian and Hindavi, is credited with the invention of khayal and tarana as well as several ragas in Hindustani classical music, developed musical instruments like the sitar, and is also known as the father of qawwali.

The celebration of Basant Panchami is but part of that vibrant weave.

It’s a day when the dargah is bathed in the quintessential colour of basant, from offerings of fresh mustard flowers to mustard turbans, tunics and sashes. Through it, the past and present are bound together in an annual seasonal cycle that hints at the possibility of outlasting all hubris of power.

Legend has it that the celebration of Basant Panchami at the dargah, complete with mustard flowers, songs in the Purabi dialect and qawwalis can be traced back to an event in the lives of Nizamuddin Auliya and Amir Khusrau.

It is said that the Auliya had been very fond of his sister’s son, Taqiuddin Nuh, who passed away at a very young age. The boy’s death affected him deeply. It was as if he had forgotten to talk or smile after the loss. His condition worried Khusrau no end.

Then came the day of Basant Panchami. Signifying the first day of a 40-day spring culminating in Holi, it falls on the fifth day (panchami) of the waxing moon in the month of Magh as per the Hindu lunar calendar.

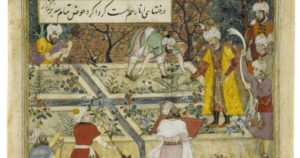

Khusrau, who was on his way to court, saw a group of Hindus, some with dhols around their necks and manjiras in their hands, singing joyously. Clad in yellow, they were carrying mustard flowers. Khusrau asked them where they were bound and they told him that since it was Basant Panchami, they were going to the Kalka temple to offer mustard flowers to their god.

At that moment Khusrau, the artist, knew what he had to do to make his god, Nizamuddin Auliya, smile and come back to life as it were.

He draped himself in a yellow sari and, accompanied by several other disciples, reached Nizamuddin Auliya’s retreat. Once there, he started doing the tawaf (the ritual of circumambulation of the Kaaba in Mecca) around the saint.

After completing each round, amid beats of dhol, the sari-clad Khusrau made offerings of mustard flowers at the Auliya’s feet, singing the following song in the Purabi dialect:

Aaj basant manaalay suhaagun,

Aaj basant manaalay;

Anjan manjan kar piya mori,

Lambay neher lagaaye;

Tu kya sovay neend ki maasi

So jaagay teray bhaag, suhaagun,

Aaj basant manalay;

Oonchi naar kay oonchay chitvan,

Ayso diyo hai banaaye;

Shaah-e Amir tohay dekhan ko,

Nainon say naina milaaye, Suhaagun,

aaj basant manaalay.

[Rejoice, my love, rejoice,

It’s spring here, rejoice!

Bring out your lotions and toiletries

And decorate your long hair.

Oh, you’re still enjoying your sleep, wake up.

Even your destiny has woken up,

It’s spring here, rejoice!

You snobbish lady with arrogant looks,

The King Amir is here to see you.

Let your eyes meet his,

Oh my love, rejoice!

It’s spring here again!]

In A Diary of a Disciple of Nizamuddin Auliya, a translation by H. Sajun of Raj Kumar Hardev’s original work in Persian, there is a description of how Nizamuddin Auliya, in tears, gets up, sings along with his devotee and begins whirling.

He then goes to the grave of his nephew where he offers his prayers and sings: ‘Ashq rayz ameedan abro bahar’ (‘Shed tears of joy at the coming of spring and the clouds’). From then on, the Auliya’s followers have ushered in Basant Panchami thus—by carrying mustard flowers, wearing yellow and singing qawwalis.

Dewan Syed Tahir Nizami, who hails from the lineage of Baba Farid (who chose Nizamuddin Auliya as his successor), explains that the festival starts from the ‘laal chabutara’ near Mirza Ghalib’s grave in Nizamuddin where the Khadims (the seat holders at the dargah), qawwals and devotees gather, wearing yellow attire, sporting yellow scarves, and holding fresh sprigs of mustard flowers.

From here, the musical procession makes its way to the shrine of Khwaja Muhammad, grandson of Baba Farid, who was very close to Nizamuddin Auliya.

After offering songs at this shrine, the procession moves towards the grave of Maulana Alauddin Nili, a ‘khalifah’ known for his piety, where there is a reading from a copy of the Fawaid ul Fuad, that Nili had made with his own hand.

In this area of Nizamuddin, which marks the final resting place of non-believers like Ghalib and also the likes of princess Jahanara and emperor Muhammad Shah Rangeela, the next halt is the grave of Taqiuddin Nuh, the nephew whose death plunged Nizamuddin Auliya into gloom. The procession halts here for a while, and a few qawwals and Nizamis go inside the small room housing his grave, while the rest wait outside. Their singing continues.

The procession then moves to the Auliya’s tomb, and on to the tombs of his beloved Khusrau, along with Abu Bakr ‘Musallahdar’ (who would carry the Auliya’s prayer mat, the ‘musallah’) and Maulana Mohiuddin Kashani (one of the senior Khalifas of the Auliya).

Usually, at the Auliya’s dargah, the qawwals, out of respect, do not enter the sanctum. In fact, they don’t even stand on the lone step which leads to the dargah. They sit right opposite the doorway of the shrine and sing. Basant Panchami is the only day when they go in for 10-15 minutes and sing to their Auliya.

In those rousing moments, when the dargah is a sea of mustard yellow and the qawwalis reach up to the sky, it is difficult to remain a mere spectator. You wait for next spring, to once again breathe in the fragrance of the Auliya’s message of love, exemplified by his beloved disciple Khusrau who created the weave of an eternal spring of cultural syncretism in the subcontinent.

(Bharat S. Tiwari is an interior designer with a passion for Hindustani literature and culture. He is the editor of Shabdankan.)