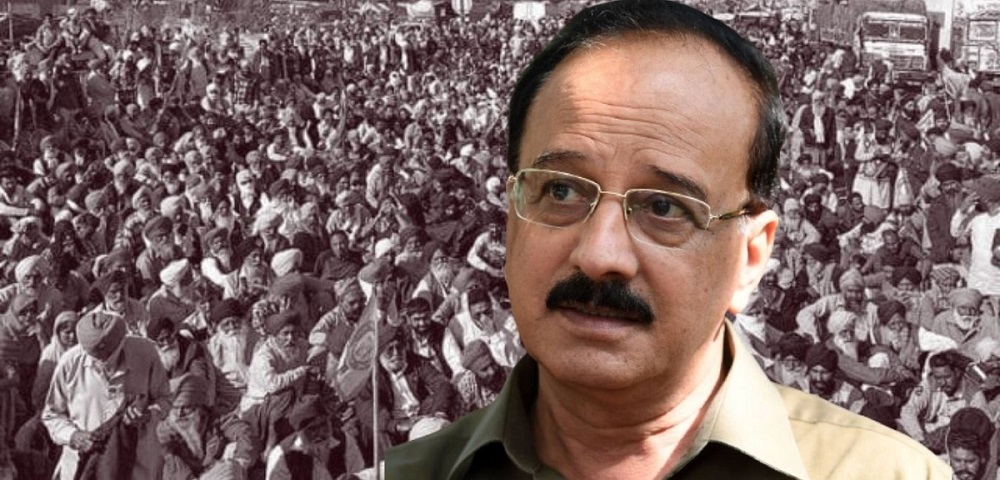

[Devinder Sharma is a distinguished food and trade policy analyst.]

Ramesh Menon: You have been travelling to the sites where farmers are agitating. What is the sense you got?

Devinder Sharma: The first thing is that the impression that many have created saying that the farmers have been misled into agitating is absolutely not true. Farmers know why they are battling a severe winter in the open. They just feel that with the new farm laws that have been passed, they need to be heard. The pain they have been living with needs to be appreciated. They have suffered long enough. This protest is an outcome of the compounded anger built over years. What the farmers are now looking for is an assured income by way of an assured price.

Farmers understand not only these laws but also the political economy behind them. That the farmers can decipher the laws and understand the intricacies has come as a surprise for the policymakers.

What is really striking is their amazing resolve of returning home only after the laws are repealed. They have repeatedly said: Bill wapsi, ghar wapsi. They have come with their families, they have dug in and said they will stay here as long as the government wants them to. They have come with bags and baggage, food supplies, tents and warm clothing.

At Singhur and Ghazipur borders, I noticed there were so many women and teenagers among the protesting farmers. There were very elderly farmers in their eighties and seventies with their grandchildren. I have never seen any protest like this anywhere in the world.

RM: The resilience of the farmers is amazing. Each one is doing something there for each other. The bonhomie and spirit to call attention to the problems in agriculture are striking.

DS: What you are saying is what Punjabi culture stands for. Just read any of the Punjabi scriptures. It is all about sharing and caring. It is not surprising to those who have seen Punjabis how they live their lives.

Punjab’s culture is agriculture. This is what most of us have not understood. Look at the protest sites. They are so supportive and helpful to each other. There are men and women cooking for thousands, they have even set up a library for those who want to read, there are scores of volunteers cleaning up, organising the protest, distributing blankets and clothes and doing everything to keep the protest going. Even those who are coming for the protest from the villages do not come empty-handed. They bring something to distribute as they know what the suffering is all about. Punjabis all over the world are supporting the protest.

We probably missed reading their inherent strength. Nobody believed that a protest could carry on like this for so long.

RM: Government spokespersons have been saying that it is only the farmers from Punjab and Haryana who are protesting.

DS: What is wrong with Punjab and Haryana farmers protesting? These farmers know that the Minimum Support Price (MSP) will ultimately go away and the mandis will become redundant. In any case, to say that rich farmers from Punjab are protesting is also wrong.

Farm households in Punjab carry a debt of Rs 1–lakh crore. A house to house survey by three public sector universities – Punjab Agriculture University, Ludhiana; Punjabi University, Patiala and Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar – had shown that between 2000 and 2015 more than 16,600 farmers and farm workers had committed suicide. Every third farmer in Punjab is below the poverty line. Therefore to say this is a protest by rich farmers is awfully wrong.

To the question of why farmers in other parts of the country are not protesting, the answer is that majority of India’s farmers have never received MSP. Only 6% of farmers get MSP in India, and the remaining 94% are dependent on markets. These farmers do not even know what they have been missing all these years.

Even Sharad Pawar had acknowledged this when as agriculture minister, he had told parliament that 71 percent of Indian farmers do not know what is MSP, they don’t understand the concept behind MSP.

Now, farmers are slowly getting aware.

RM: What are the implications of this agitation?

DS: It has an impact not just on India but has tremendous international implications. Once Indian farmers provide a model, the rest of the world also would like to follow that. Therefore it has huge implications.

Farmers in the United States and Europe are also facing a severe agrarian crisis. They are being driven out of agriculture despite getting huge subsidies. This is happening in rich countries that had adopted market-oriented agricultural reforms some six to seven decades back. Europe provides 100 billion dollars in subsidies out of which 50 percent goes as direct income support. Despite this, one farmer quits agriculture every minute in Europe. In the US, since the seventies, 93 percent of the dairy farms have closed down. But milk production has gone up as the corporates have got into dairying and set up mega-dairy farms.

The crisis has been there for several years. I remember a tragic farm suicide in America, I can’t ever forget that. About 13 years ago, one dairy farmer first shot each of his 51 cows and then he shot himself. This shows the distress that prevailed.

If markets are so good why would the US provide 62,000 dollars as a subsidy to farmers? Why should Europe provide such huge subsidies? Take the case of the dairy sector in the United Kingdom. In the nineties, there were about 32,000 dairy farms in the UK. But after the UK dismantled the Milk Marketing Board, which regulated prices, prices crashed. Today, there are just about 8,000 dairy farms left. Dairy farmers are struggling to cover up their cost of production. What does this tell you? It tells you that market-oriented agriculture invariably comes at the cost of small farmers. Remember, when Richard Nixon was the US President, and this was in the early seventies, his agriculture secretary had said: “Get big or get out.”

Even the Director-General of Washington DC-based International Food Policy Research Institute has suggested that India should follow a policy of: “Move up or move out.”

But the bigger question is if we move a large section of small farmers out of agriculture what do we do with 50 percent of our population engaged in agriculture where 86 percent of our farmers own less than five acres? Why do we have to abandon them and not instead make agriculture sustainable? Why are we copying failed policies from the west?

At a time when we have jobless growth, why do we want jobless agriculture? Why do we entrust corporate to produce food when our farmers are capable of doing it?

RM: You mean to say market-oriented agriculture has failed to prop up farm incomes.

DS: Well, policymakers are saying that these reforms will help increase farm incomes. It will increase the bargaining power of small farmers, and thereby help enhance their incomes. But a study by the London School of Economics has shown that similar reforms in Kenya, where farmers have small holdings, have failed and pushed farmers deeper into crisis.

I remember a report of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) which had concluded that between the mid-eighties and mid-2000, a period of 20 years, the output price globally had remained static if you adjust for inflation. Rich countries compensated farmers with subsidies. Poor countries had no money for subsidies.

Another study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) along with ICRIER had estimated that said that between 2000 and 2016-17, Indian farmers lost Rs. 45 lakh crores. That meant it every year farmers lost approximately Rs 2.64 lakh crore. was lost! It happened at a time when 94% of farmers were dependent on markets.

Globally too farmers have suffered the markets. Farmers all over the world are hurt by the volatility of the market.

Take for instance the coffee industry. It has a turnover of 102 billion dollars. There are around 50 to 60 million coffee farmers in the world. For the last 13 years, the prices of coffee beans have been depressed. As a result, a majority of these coffee farmers have an income level of less than 1.9 dollars a day which falls within the acute poverty line according to the United Nations.

Look at cocoa. The confectionary industry is worth 210 million dollars. The cocoa farmers get only 1.3 dollars a day which is less than the price of an average chocolate bar that you buy. This is at a time when bulk of cocoa and coffee were traded on the commodity exchanges. Imagine if these farmers had MSP. Wouldn’t their livelihoods would have been much better?

RM: Alright. But what are the agitating Indian farmers so angry about?

DS: Farmers are angry over the neglect and injustice they have faced over the past few decades. They fear that these farm laws have been designed for the corporate, not for farmers. The compound anger of all these years is perhaps what is coming out.

Look at their plight. There are reports every now and then of farmers throwing tomato, potato and onions on the streets. See what they get for their produce. In Madhya Pradesh, farmers got one rupee for a kilo of bhindi while in the urban market it was selling for Rs. 40 a kilo. Look at the brutality of the markets.

Economic Survey 2016 told us that the average income of a farming family in 17 states of India is only Rs. 20,000 a year, which means less than Rs. 1,700 a month. Have we ever pondered how are these farming families surviving? Hasn’t society at large failed to stand up for the farmers? Did we ever call for economic justice for farmers?

Because the intelligentsia, the academia and the media failed to stand for farmers, they realise they have to stand for themselves. After all, farmers also have families to look after. They have to take care of the education and health expenses of their family. They also want to live a better life.

All that the Farmers are essentially asking for is an assured price for their crops. They want MSP as a legal right for 23 crops for which MSP is announced every year. Farmers too need an economically viable system to survive.

RM: What kind of reforms do you envisage?

DS: Instead of borrowing from abroad, our emphasis should be on creating our own models, banking on our own strengths, our own needs and requirements. We should we aiming at reforms that provide more income in the hands of small farmers, making agriculture sustainable and economically-viable thereby achieving the Prime Minister’s vision of Sabka Saath Sabka Vikas.

First, make MSP a legal right for farmers. The delivery of MSP has remained confined to primarily two crops – wheat and paddy – and that too predominantly in Punjab and Haryana, where farm incomes are relatively higher than the rest of the country. It is time to extend this to the entire country, and to all the 23 crops for which MSP is announced every year. This means basically upping the benchmark prices to ensure that no trading takes place below MSP. This means the private trade too will need to make purchases at MSP or above. It does not mean that the government will have to procure everything.

Secondly, to ensure smooth marketing, the network of APMC regulated markets needs to be expanded to reach every nook and crook. Against the 7,000-odd PMC mandis that exist today, we need a network of 42,000 APMC mandis if a mandi has to be provided in a radius of five kms. We also know that there are problems with the working of APMC mandis. The mandi structure needs to be reformed, not thrown away. Regulated markets are absolutely essential for price discovery.

And finally, we need an alternative system that can provide more money in the hands of farmers. In America, as per the US Department of Agriculture, farmers share in every food dollar a consumer spends is only 8 percent. Why emulate a system that aggravates agrarian distress? What we need is to learn from our own Amul dairy cooperative design that provides at least 70 percent share of the end consumer price to farmers. We need to launch a nationwide programme to replicate the Amul model to vegetables, fruits and pulses.

(Ramesh Menon is the author of six books, a documentary filmmaker, educator and Editor-in-Chief of The Leaflet. Article courtesy: The Leaflet.)