As Truth-Tellers Get Arrested, We Must Tell Our Children the Truth

“I don’t know what ‘Teesta’ is. What riots are they talking about?”

The class 12 student’s response to a video about a citizens’ protest at Jantar Mantar on June 27 would have been funny if it hadn’t been so startling. This 18-year old has studied all her life in a well-known school in the National Capital Region but had no idea either about the Gujarat pogrom of 2002, Teesta Setalvad, or about the protests that have taken place demanding her release.

For me, it was a moment of realisation. First, that Indians who are currently in their late teens or early twenties are unaware of the impact that events such as the Babri Masjid demolition or the Gujarat riots have had on the India that they live in. Second, it is easy to assume otherwise.

To her credit, though, the young woman wanted to know more. As a science student, she said, she had stopped studying Indian history – ancient, medieval or modern – in class 10 itself, and asked me to please tell her about these riots.

I hesitated. We like to shield the young from the horrors of the world for as long as we possibly can, but here was an open mind that wanted to learn. And so I gave a brief synopsis of the 2002 pogrom and the events that led up to it, citing various books, interviews and articles to corroborate what I was sharing.

I told this student that the majority of those who were killed had been Muslim, including an ex-MP called Ehsaan Jafri who was murdered in the most brutal way by a mob in Ahmedabad, despite several frantic calls to the police for help. Hesitatingly, I also spoke of the women who were assaulted and killed, but also that many who had led those mobs were finally sentenced to prison, thanks to the untiring efforts of human rights activists and lawyers like Teesta Setalvad and others.

I also told her that those who had been found guilty and convicted by the courts are now out on bail and those like Teesta who have struggled tirelessly to get justice for the victims are now in jail. Hence, the protests at Jantar Mantar and elsewhere.

Suffice it to say, the student was stunned.

“Does everyone in India know this?” she asked. “How come I don’t know any of this?”

I apologised if I had ruined her day. Waving the apology aside, she said, “I think I know why I don’t know all this. Because at home they only watch TV channels that worship Modi.”

She went on to tell me how most members of her family genuinely believe that Muslims are ‘dangerous’, and how this has always bothered her. “How can you blindly side with people from one community while completely demonising another?”

I was encouraged to see that this young person’s sense of right and wrong was still intact, and that she was disturbed by the bigotry around her. The next day, she told me she had challenged the prevailing narrative in her family by sharing on her family WhatApp group what she had learned about Gujarat 2002. What amazed her was that no one had been able to come up with a factual rebuttal to what she had shared!

I was reminded of a similar conversation I had had with 200 school children a few months prior. Two senior school teachers, again from a private school in the National Capital Region, had requested me to give a talk to their class 8 students about the farmers’ protest after they learned I had spent a fair amount of time documenting it. I agreed, but thought it fair to tell them, “This is a controversial topic, there be objections from some parents.”

There was a moment’s silence and one of the teachers said, “We know. We’ll take the chance. We are social science teachers and it’s important that our kids hear about this protest from someone who was part of it, and get a perspective other than the one they see all the time on TV.”

Touched by their concern for the students, I took my time preparing. As this was in the days while schools were still physically closed, the session took place online. I began by showing the 8th graders a map of Delhi and exactly where Singhu, Tikri, Ghazipur and Shahjahanpur borders are, where tens of thousands of protesting farmers had spent over a year. I showed them TV clips from November 26, 2020, the day the farmers reached Delhi and how the farmers simply pitched camp despite the violence inflicted on them and refused to budge.

As expected, a student asked, “But why were they protesting?”

To that, I showed slides outlining the poverty and debt Indian farmers live in and how the new farm laws would have meant further disempowerment and ruin. We then spent the better part of an hour watching video footage from the protest showing the farmers’ resilience, generosity and deep commitment to Gandhian non-violent protest. The students were moved as they watched the farmers’ gentle courage and their genuine hospitality towards any who visited them.

They were also inspired by how erudite and well-informed the farmers were, and somewhat aghast at how one-sided and biased media coverage of this protest had been.

One of those students sent me a short, but moving e-mail a couple of days later:

“As a citizen of India I know I need to do something. No matter how dark things may seem, I want to help and make things better and the only way to do that is to start with small steps.”

At a time when human rights activists like Teesta Setalvad and fact-checkers like Mohammed Zubair are being arrested for speaking the truth, and normal hope seems all but lost, that 40-word email from a Class 8 student gives me strength, comfort – and the direction I need.

(Rohit Kumar is an educator and trainer. Courtesy: The Wire.)

❈ ❈ ❈

Protesters Demand Release of Teesta Setalvad, Sreekumar, Seek Review of SC Order

Courtesy: Counterview

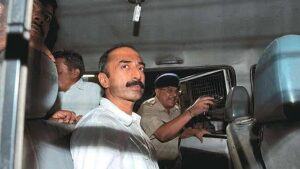

Protests broke out across India on June 27 following Teesta Setalvad’s arrest demanding her immediate release. Sabrang India, a site run by Setalvad, claimed she was “arrested on trumped-up charges after the Supreme Court dismissed the petition moved by Zakia Jafri demanding an investigation into the larger conspiracy behind the 2002 Gujarat violence.” The protesters also demanded release of former DGP Gujarat police RB Sreekumar, also arrested simultaneously.

The protests were preceded by over 2,200 people from across the globe signing a statement demanding their immediate release. Among the leading signatories were People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) general secretary V Suresh, National Alliance of People’s Movements (NAPM) convenor Medha Patkar, and former Naval chief Admiral Ramdas.

“The state has used the observations made in the judgment to falsely and vindictively prosecute those who had struggled for justice even in the face of state callousness and complicity. It is truly an Orwellian situation of the lie becoming the truth, when those who fought to establish the truth of what happened in the Gujarat genocide of 2002 are being targeted,” the statement said. They appealed to the apex court to review its own judgement, which had triggered the arrests.

“The ordinary process of litigation to make the state accountable by establishing guilt of those accused of serious crimes is tarred with the criminal brush. We condemn this naked and brazen attempt to silence and criminalize those who stand for constitutional values and who have struggled against very difficult odds to try to achieve justice for the victims of 2002. We demand that this false and vindictive FIR be taken back unconditionally and Teesta Setalvad and others detained under this FIR be released immediately,” said the signatories.

In Bengaluru, activists protested at Town Hall in solidarity, holding posters demanding the release of Setalvad and Sreekumar. Two persons were detained during the protest. Earlier, the All India Lawyers Union (AILU) had expressed solidarity with Setalvad. On Monday, young lawyers held a protest outside the City Civil Court complex.

In Kolkata, activists gathered on June 27 at Moulali and Rajabazar areas to condemn the arrests. Earlier, Earlier, on June 26, the West Bengal’s Left organisations organised a march in Kolkata demanding the immediate release of Setalvad and Sreekumar. Participants included Left Front chairman Biman Bose, actor Badsha Maitra, social activist, Saira Shah Halim and CPI-M state-secretary Mohammad Salim.

In Delhi, the All India Union of Forest Working People (AIUFWP) leaders Ashok Chowdhary and Roma Malik, social activist and filmmaker Gauhar Raza, Prof Shamsul Islam, Democratic Teachers’ Front president Nandita Narain joined protesters gathered at the Jantar Mantar to demand justice for Setalvad and Sreekumar. Attendees chanted “Free all political prisoners”.

In Varanasi, the Nagrik Samaj – which included academics, social activists, lawyers and media persons – submitted a memorandum to the Additional Chief Judicial Magistrate a memorandum demanding release of Setalvad and Sreekumar. Protesters, including Senior Samajwadi Party leader Vijay Narayan Singh, Sunil Sahasrabuddhe, Professor R P Singh, Aflatoon, Lenin, Rajendra Chaudhary, Manish, Praval, farmer leader Ramjanam, Luxman Prasad, Advocate Abdullah and Abu Hashim, showed their support to Setalvad.

People gathered and sang songs of solidarity while a person held a poster with the words “I am Teesta”. Citizens for Justice and Peace Varanasi coordinator and social activist Muniza Khan said, “We demand the release of Setalvad and Sreekumar. Regarding the Supreme Court decision, we see for the first time that the petitioner herself is being questioned. We appeal to the court to reconsider this decision.” Protests were shortlived owing to security pressure.

In Mumbai, activists gathered outside Dadar railway station demanding immediate release of Setalvad and Sreekumar. The protesters, including trade unionists, demanded that the ruling regime stop abusing their power. In Thiruvananthapuram, a protest meeting was held in front of the Secretariat, It was organised by the Purogamana Kala Sahitya Sangham. There were also protests in Jaipur, Ranchi, Ajmer, Ahmedabad, Bhopal, Lucknow, Allahabad, Chandigarh, Chennai, Dhulia, Raipur. etc.

(Counterview is a newsblog that publishes news and views based on information obtained from alternative sources, which may or may not be available in public domain, allowing readers to make independent conclusions.)