Soumitra Ghosh

As per recent data, India now has 1,117 active COVID-19 cases and 32 deaths due to the outbreak of coronavirus in the country. Quite alarmingly, the known respiratory disease COVID-19 cases have increased exponentially in the last couple of weeks. Even in a mild scenario with an attack rate of 5-10% and a case fatality rate (CFR is the number who die relative to the number infected) of presently 2.9%, the number of deaths would jump to a thousand soon. The total number of deaths due to novel coronavirus is doubling every two days in India.

The pertinent question is how do we deal with this COVID-19 epidemic? What policy options do we have? A few short term and long term strategies have already been at work. First, testing would help detect the virus at source, prevent secondary infection and reduce mortality. After facing severe criticisms for,, the government has decided to extend testing to all pneumonia patients.

But the number of government labs (only 117) conducting tests for COVID-19 continue to be grossly inadequate. Although a few private facilities (43) got approval in some states it is anybody’s guess that how many from the lower socioeconomic strata would turn up for testing at private labs, given that the cost of a test would require at least three days of wages for an unskilled worker in India, even if indirect costs are ignored. The problem is that unless we get population level figures i.e., the true number of cases in the population, it is hardly possible to make reasonable policy decisions. It would be therefore highly desirable that tests are conducted free of cost among a sufficiently large random sample of people to estimate the prevalence of coronavirus disease. To start with, the exercise can be carried out first in Kerala and then in Maharashtra, states with most number of confirmed cases of COVID-19. This would enhance our understanding of the disease transmission.

On day three of the lockdown, a video showing children eating grass with salt in a village in Varanasi went viral. The impact that three weeks of lockdown will have is unimaginable. Aside from economic woes, the wide-spread panic caused by the lockdown and misinformation might see patients with serious ailments avoiding hospitals for the fear of contracting COVID-19. Further, the non-availability of transport may also prevent people from accessing medical treatment, particularly in rural areas.

Let us look at other deterrents – vaccine and drugs. The vaccine can prevent one from getting infected but it is still quite some time away (at least 12-18 months). This means that we need to focus on the health care system, which can save millions of lives by using an aggressive treatment approach in dealing with COVID-19 affected patients. The evidence on coronavirus epidemic indicates that the case fatality rate varies considerably across countries and over time, ranging between 0.37% and 11.23% and some of the factors that affect the higher death rates are coexisting diseases, low quality health services and patient demographics.

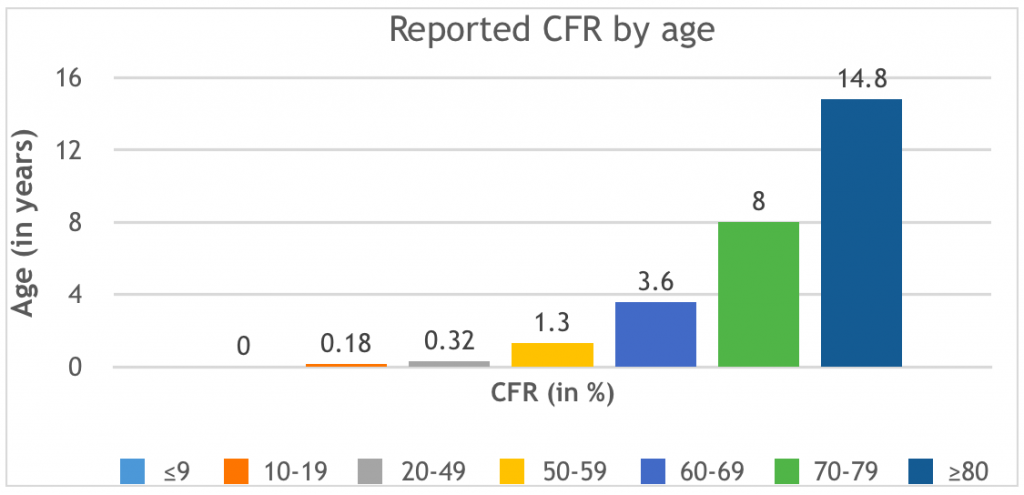

According to a report based on 72,314 COVID-19 cases by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CCDCP), the age distribution of the infected persons is as follows: between 30 and 79 years accounted for 87% of the cases, ≤9 years for 1%, 10-19 years 1% and aged 80 years or older 3%. There were a total of 1,023 deaths out of 44,672 confirmed cases. In other words, the overall CFR was 2.3%. However, the reported CFR differed significantly by age.

Evidently people from the older cohort (60+) are highly susceptible to coronavirus and have higher mortality rate. Importantly, China is not an exception as similar mortality patterns were observed in other coronavirus affected countries including India. In India, out of 25 deaths, 80% were aged between 60 and 85 and the average age of the deceased persons was 64 years.

Worryingly, there are 117 million people in this country who are aged 60 and above and about one-fourth of them, according to National Sample Survey 2017-18 data, are having at least one chronic disease. As the epidemic intensifies, there will be a spurt in demand for hospital care, particularly from older Indians, with an estimated 5-10% of total cases needing critical care with invasive and non-invasive ventilators, advanced radiology, ICUs etc.

In absolute numbers, in the worst-case scenario, there could be an estimated 22 lakh severe hospitalisation cases by May 15. This is a disturbing figure, because the health care system does not have the capacity to deal with such a large number of cases. According to one estimate, India has only 3.63 public ICU beds per 100,000 population and the per capita availability of ICU beds varies tremendously both between and within states.

For instance in Madhya Pradesh, out of the 50 districts, as many as 30 districts had no ICU facility in 2015 (Saigal et al 2017), and more than two-thirds of the facilities were concentrated in just four districts. MP had only 2.5 ICU beds per 100,000 population, and 83% of these were in the private sector and almost 9 out of 10 facilities were of low quality, implying that they either lack sophisticated equipment, such as non-invasive ventilator, facility for ABG etc., or qualified medical doctor.

It is evident that there would be a significant short-fall to match the intensive care need, even under an optimistic scenario (where there will be less number of hospitalisation cases). To put in perspective, Italy, which is similar in size and population density to Madhya Pradesh, has 26 ICU beds per 100,000 population. Yet, the pandemic has overstretched its health system, forcing it to delay non-urgent surgical operations and free up ICU beds for patients infected with COVID-19.

Besides, low number and quality of ICU beds, the skewed distribution and private ownership of facilities are going to be the key barriers to patient care access, specifically for the middle and lower middle-class population in India. The access related issues are similar across India, barring one or two southern states where the health care infrastructure is relatively better. This is the direct fall out of the relentless persuasion of privatisation in health care and weakening of the public health system, which has put millions of older people at danger as they are highly susceptible to COVID-19 and have higher mortality rate. Although any death is unwarranted, the deaths due to avoidable reasons are more painful than the unavoidable ones.

In terms of the health system’s capacity, India is among the least prepared countries to deal with the pandemic. Currently, almost all COVID-19 positive patients are being treated at public hospitals. The Centre’s provision of Rs 15,000 crore for infrastructural upgradation is going to be too little to make any major impact. For example, the estimated total number of ventilators in the country is between 30,000 and 50,000, whereas we would need at least 200,000 ventilators.

Both the Centre and states must find additional resources, which can be used for creating isolation wards, expanding the existing ICU facilities and for purchasing critical care equipment like ventilators. Media reports suggest that in many public hospitals doctors, nurses and frontline workers who are putting their lives at risk for the rest of us are yet to be provided with respiratory masks, surgical gowns and protective eye gear. The neglect of healthcare providers can prove to be very costly. If we do not protect them, how will they protect the patients? Regardless of technical equipment, shortage of healthcare workers would remain a significant area of concern. The issue of not having enough qualified doctors, trained nurses and support staffs such as physiotherapists, ICU technician etc., would severely undermine efforts to treat COVID-19 affected patients. Years of neglect cannot be overcome overnight.

In states like Bihar and UP, the public facilities would have to manage with 30% human resources of what ideally is required, even after pooling the medical and paramedical staff from the private sectors. This would obviously affect the performance of these facilities and in turn, treatment outcomes. To address this issue, West Bengal decided to recall the retired doctors. This would give them some breathing space. We can take a few more steps.

There are at least ten thousand medical and paramedical students who are currently studying management programmes (including hospital and public health management) in different institutions across India. They should be brought in. This would be an excellent internship opportunity for them.

In addition, another few thousand public health and hospital administration graduates with training in different streams of medicine currently engaged in administrative works in NGOs may also be called in. Finally, we have more than 100,000 registered dental graduates in India, who could prove to be an excellent resource. All of them should be recruited and trained at an early stage so that they can also be used in crisis situations.

It is likely that the demand for hospital care, in particular, advanced care will overwhelm the public health system soon and therefore, tapping the private sector to fill the gap may be a good idea at that point, but it should be treated as a stop-gap solution and treatment must be provided free to all. It is important to remember that the private sector actually has very little to offer in resource-poor settings, where it is actually needed, if one were to work with the private providers for improving access.

For example, in Bihar, there is no registered private provider (i.e., no hospital was empanelled with insurance companies) in 14 out of the 38 districts, according to the analysis based on data from Insurance Information Bureau of India data (Choudhury and Dutta 2019).

In such locations, the public hospital is the only provider and public-private partnerships such as PMJAY play a very insignificant role. Therefore, instead of using PMJAY and other PPP routes to nudge the private sector to capture greater space in health sector, resources should be channelised to augment the capacity of the public health care system to deliver care.

(Soumitra Ghosh is Assistant Professor at the Centre for Health Policy, Planning and Management, Tata Institute of Social Sciences.)

***

Editorial addition: Anjali Chikersal, in an article “The Pandemic Should Serve as a Wake up Call to Revamp Public Healthcare” published in The Wire adds:

The coronavirus pandemic surging throughout the world has well and truly reached India…. It is a worrisome situation given India’s population, the living conditions of the vast majority, and the current state of our healthcare system. But can it force the Indian government to do what it has so deliberately neglected over the last several decades? Can it compel the government to strengthen our public health system as so direly needed, not just for the moment but for the long term? …

The private health sector in India has flourished in the past three decades at the cost of the public sector. Budgetary allocation for health has consistently fallen way short of that recommended by experts. The government has ignored the desperate appeals for strengthening public hospitals all these years.

Instead, it has employed a deliberate shift from publicly provided healthcare and propped up the private healthcare industry and now private health insurance. The result, as to be expected, is a public health sector that seems about to come undone now that an unprecedented challenge to healthcare has suddenly surfaced.

It is in this scenario that healthcare staff at government hospitals will risk their lives in the fight against the coronavirus. The private sector may have more beds and more personnel, but it also has no obligation to treat. It may take in patients, but only as many as it comfortably chooses to. It will not treat more than it has the capacity or desire for. Nor will it invest in augmenting its capacities for a crisis that is, however serious and massive, a temporary one. The onus for that falls on the public health system. Hence the government’s has upped its frenzied efforts to increase it’s healthcare capacities – beds, ICUs, equipment, medicines – across the country.

But what happens outside this crisis scenario? What was the case three months ago when no one had heard of COVID-19? The poor and the marginalised, and even the middle class, faced the same shortage of critical treatment options every single day even then. They struggled to find care, they suffered from unaffordable and inaccessible services, and many died – as they will continue to do when this pandemic subsides unless there is a drastic restructuring of our health system.

The Indian population faces a remarkable shortage of healthcare personnel and infrastructure. There is only one government doctor for more than 11,500 people in India as opposed to one for every 1,000 as recommended by the WHO; only one government bed for about 2,000 people; medicines are in constant short supply; the private health sector is completely unaffordable, and whatever services are available are significantly skewed towards the benefit of the rich and the urban.

Estimates suggest that deaths due to COVID-19 may fall between 30,000 and 170,000 in India. However tragic this figure may be, it is far lower than the 2.4 million deaths caused annually due to poor quality and lack of healthcare where and when it is needed most, or the misery of poverty that 55 million Indians face each year due to healthcare costs.

What the government needs to do … is to build up the public health system on an ongoing steady basis. It needs to inject the necessary funds … It needs to show that it is committed to providing healthcare to its citizens every day, not just today, not just in case of exigencies. The government has the moral duty to ensure that healthcare is available and accessible to every citizen even when there are no cataclysmic sudden needs. If the current pandemic is proof of anything, it is that there is no substitute for publicly provided healthcare. In short, it is time to breathe life not just into desperately sick COVID-19 patients but into our entire public healthcare system.

The coronavirus pandemic has the potential to cause untold damage and loss but it can also serve as a greater good if our government wakes up from its self-induced slumber and converts an emergency augmentation of public health services into a long-term overhaul.

***

Editorial addition: Sanjeev Kumar, in an article “Why the ‘Gujarat Model of Development’ Has Seen the Highest COVID-19 Fatality Rate” published in The Wire points out that PM Modi’s entire approach to health care, his lack of concern for providing health care for India’s poor masses, is evident from the state of Gujarat’s health care system, where he was Chief Minister for 13 years:

Data updated by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare on the evening of April 7 indicated that the fatality rate due to COVID-19 in Gujarat is the highest among all states and union territories of India.

The total number of infected persons reported in Gujarat was at 165, with 13 deaths. Thus the fatality rate in Gujarat is 7.88%. The fatality rate of COVID-19 in India as a whole is 2.87%.

The high fatality rate in Gujarat perhaps reflect the alarming conditions of the public health system in the state. There is a need to understand this, particularly since Gujarat has been projected as the model state in the past for India to follow.

It was only after the total lockdown was imposed throughout India that the Gujarat government started the process of reserving hospitals for treating patients with COVID-19 exclusively, procuring 156 ventilators and training its 9,000 health workers to manage ventilators. This lack of urgency reflects the poor condition of public healthcare in Gujarat.

Gujarat has a legacy of a bad public healthcare system. The four terms of Narendra Modi as chief minister of the state played an important role in creating this legacy….

Currently, Gujarat has 0.33 hospital beds per 1,000 population. There is only one state that has smaller ration – Bihar. The national average is 0.55 beds per 1,000 population.

Gujarat was ranked 17 among the 18 largest states in India by the Reserve Banks of India in terms of social sector spending. Gujarat was spending only 31.6% of its total budgetary expenditure on the social sector.

In terms of per capita health expenditure, Gujarat’s rank slipped from fourth in 1999-2000 to 11th position in 2009-10…. In 1999-2000, Gujarat was spending 4.39% of its total state expenditure on health, but by 2009-10 this came down to 0.77%….

In Gujarat, Out of Pocket Expenditure on Healthcare (Hospitalisation) in government hospitals is higher than the national average and higher than even states like Bihar. This means those visiting government hospitals in Gujarat have to spend more money from their own pockets than the people in Bihar have to. In terms of per capita spending on medicine, Gujarat ranked 25th in 2009-10.

In 2001, when Modi became the chief minister of Gujarat, the state had a total of 1,001 primary health centres, 244 community health centres and 7,274 sub-centres. In 2011-12, while the number of the primary health centres and community health centres marginally increased to 1,158 and 318, the number of sub-centres remained the same. Even today the total number of primary health centres in Gujarat is less than even Bihar. The total number of public rural hospitals in Bihar is almost three times of the total number of rural public hospitals in Gujarat.

(Sanjeev Kumar is a senior researcher at Tata Institute of Social Science.)