Climate Crisis: An Emerging New Arctic

Countercurrents Collective

A new Arctic is emerging. The regions landscape is changing rapidly. Temperatures are skyrocketing, sea ice is dwindling and many experts believe the far north is quickly transforming into something unrecognizable.

This week, new research confirms that a new Arctic climate system is emerging.

A new Arctic will be warmer, rainier and substantially less frozen. Animals that used to be common may disappear, while new species may move in to take their place. Opportunities for hunting and fishing by sea ice could dwindle. Shipping in the Arctic Ocean may significantly increase as the ice disappears.

Planning for disasters may be an increasingly difficult task.

Community planners often design infrastructure, made to last a certain number of years or withstand a certain level of stress, by looking at past weather observations. But as the Arctic climate transforms, the past is no longer a good predictor of what to expect in the future.

Some aspects of the Arctic climate have already changed beyond anything the region has experienced in the past century. Sea ice extent has shrunk by 31% since the satellite record began in 1979. Patterns in ice coverage today have dropped beyond the bounds of anything that would have been possible just a few decades ago.

By the end of the century, if global temperatures continue to rise unchecked, other key elements of the Arctic climate including air temperatures and precipitation patterns could also be profoundly different from the former 20th-century “normal.”

Study co-authors Laura Landrum and Marika Holland, researchers at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Colorado, U.S., published their findings on September 14 in the journal Nature Climate Change.

The study, they say, is among the first to examine the timing of the emerging new Arctic — the point at which climate conditions fall outside even the furthest boundaries of what was previously “normal” — across both sea and land.

“The changes are so rapid and so large that the Arctic [has] warmed so significantly that its year-to-year variability is moving outside the bounds of past fluctuations, signaling a transition to a new climate,” Landrum told E&E News.

Landrum and Holland have used large ensembles of climate models to investigate how the Arctic climate has changed over the last century and what kinds of changes may be in store over the next 100 years.

They focused on a severe hypothetical climate scenario — a trajectory many scientists think of as the worst-case scenario if human societies do nothing to curb their greenhouse gas emissions.

The scientists specifically examined changes in Arctic sea ice extent, air temperatures and precipitation patterns.

The scientists have found: Sea ice has already declined beyond the bounds of anything that would have been seen even a few decades ago. In other words, at least one signal of the new Arctic — driven by climate change — has already emerged.

And sea ice declines will only get worse as time goes on. Under the extreme climate scenario, summer sea ice extent will fall below 1 million square kilometers — a threshold so low most scientists consider the Arctic Ocean “ice free” at that point — by the 2070s at the latest, and potentially decades earlier.

Air temperatures are likely to cross the threshold by the middle of this century, with fall temperatures changing the fastest.

Changes in precipitation — namely, a transition from snow to rain — will represent a new Arctic shortly afterward.

That makes sense, considering the way different aspects of the Arctic climate system are linked.

Sea ice can have a profound effect on Arctic temperatures. Ice has a bright, reflective surface that helps beam sunlight away from the Earth. Thick sea ice also helps insulate the ocean, trapping heat below the surface in the winter and preventing it from escaping into the cold Arctic air.

As sea ice thins and disappears, the ocean is able to absorb more heat in the summer.

And in the winter, that heat is able to escape through the thinner ice and warm up the atmosphere.

“You would expect ice to play a role in warming the temperature because of these feedbacks,” Landrum said.

The rising temperatures, in turn, help speed up the transition from snow to rain.

The findings confirm that a new Arctic is already emerging — and that if global temperatures keep rising at their current pace, the transformation to an unrecognizable climate system could be complete before the end of this century.

It is a clear sign that climate change isn’t a problem for the future — it’s already dramatically reshaping the planet today. It is also a huge concern for the Arctic ecosystem and the human communities that rely on it.

“We’re entering a period where the previous observations we have do not and cannot describe the time that we’re entering,” Landrum said.

While the study provides a grim snapshot of a possible future, it is not necessarily inevitable. Other studies have indicated that a more moderate climate scenario — one in which world nations substantially reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the coming decades — could stall or prevent some of these changes.

But the research does demonstrate that immediate action is needed.

“For those living in the Arctic — whether it’s human, animal, plant — climate change is not something in the future,” Landrum said. “It’s something that’s happening now.”

The study report – “Extremes become routine in an emerging new Arctic” – by Laura Landrum and Marika M. Holland (Nature Climate Change, 2020) said:

The Arctic is rapidly warming and experiencing tremendous changes in sea ice, ocean and terrestrial regions. Lack of long-term scientific observations makes it difficult to assess whether Arctic changes statistically represent a “new Arctic” climate.

The scientists have used five Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 5 class Earth system model large ensembles to show how the Arctic is transitioning from a dominantly frozen state and to quantify the nature and timing of an emerging new Arctic climate in sea ice, air temperatures and precipitation phase (rain versus snow).

The results suggest that Arctic climate has already emerged in sea ice. Air temperatures will emerge under the representative concentration pathway 8.5 scenario in the early- to mid-twenty-first century, followed by precipitation-phase changes. Despite differences in mean state and forced response, these models show striking similarities in their anthropogenically forced emergence from internal variability in Arctic sea ice, surface temperatures and precipitation-phase changes.

(Countercurrents.org is a non-partisan India-based news, views and analysis website, that takes “the Side of the People!”)

❈ ❈ ❈

Antarctica: Cracks in the Ice

Countercurrents Collective

Satellite images show that two important glaciers in the Antarctic are sustaining rapid damage at their most vulnerable points, leading to the breaking up of vital ice shelves with major consequences for global sea level rise.

In recent years, the Pine Island Glacier and the Thwaites Glacier on West Antarctica has been undergoing rapid changes, with potentially major consequences for rising sea levels.

The scientists have found that while the tearing of Pine Island Glacier’s shear margins has been documented since 1999, their satellite imagery shows that damage sped up dramatically in 2016.

Similarly, the damage to Thwaites Glacier began moving further upstream in 2016 and fractures rapidly started opening up near the glacier’s grounding line, which is where the ice meets the rock bed.

However, the processes that underlie these changes and their precise impact on the weakening of these ice sheets have not yet been fully charted.

A team of scientists including some from TU Delft has now investigated one of these processes in detail: the emergence and development of damage/cracks in part of the glaciers and how this process of cracking reinforces itself. They are publishing about this in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. (Stef Lhermitte, Sainan Sun, Christopher Shuman, Bert Wouters, Frank Pattyn, Jan Wuite, Etienne Berthier, Thomas Nagler. Damage accelerates ice shelf instability and mass loss in Amundsen Sea Embayment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Sept. 14, 2020; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1912890117)

The scientists have combined satellite imagery from various sources to gain a more accurate picture of the rapid development of damage in the shear zones on the ice shelves of Pine Island and Thwaites.

This damage consists of crevasses and fractures in the glaciers, the first signs that the shear zones are in the process of weakening. Modeling has revealed that the emergence of this kind of damage initiates a feedback process that accelerates the formation of fractures and weakening.

Human-induced warming of our oceans and atmosphere because of the increasing release of heat-trapping greenhouse gases is weakening the planet’s ice shelves.

This ocean warming has increased the melting and calving (the breaking off of ice chunks) of Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers, studies show, while declining of snowfall means the glaciers can’t replenish themselves.

The damage researchers found pointed to a weakening of the glaciers’ shear margins – areas at the edges of the floating ice shelf where the fast moving ice meets the slower moving ice or rock underneath.

According to the scientists, this process is one of the key factors that determine the stability – or instability – of the ice sheets, and thus the possible contribution of this part of Antarctica to rising sea levels.

They are calling for this information to be taken into account in climate modeling, in order to improve predictions of the contribution these glaciers are making to rising sea levels.

The study comes on the heels of research published last week that found deep channels under the Thwaites Glacier may be allowing warm ocean water to melt the underside of its ice.

The cavities hidden beneath the ice shelf are likely to be the route through which warm ocean water passes underneath the ice shelf up to the grounding line, they said.

Over the past three decades, the rate of ice loss from Thwaites and its neighboring glaciers has increased more than five-fold. If Thwaites were to collapse, it could lead to an increase in sea levels of 64 centimeters.

On September 14, scientists announced that a 44-square-mile chunk of ice, about twice the size of Manhattan, has broken off the Arctic’s largest remaining ice shelf in northeast Greenland in the past two years, raising fears of its rapid disintegration.

The territory’s ice sheet is the second biggest in the world behind Antarctica’s, and its annual melt contributes more than a millimeter rise to sea levels every year.

❈ ❈ ❈

Greta Thunberg Champions the Plight of Climate Refugees

Courtesy: MR Online

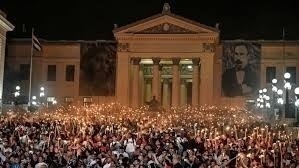

Climate campaigner Greta Thunberg urged world leaders on September 10 to consider the fate of the world’s poorest people before decisions are made about climate policy.

Tweeting about a new report from the Institute for Economics and Peace, released the same day, she simply said:

“Climate crisis could displace 1.2 billion people by 2050.”

The pain and suffering represented by the figure that the Ecological Threat Register (ETR) has produced is hard to imagine.

The ETR measures the ecological threats countries are currently facing and provides projections to 2050. Its inaugural report states that 19 countries with the highest number of ecological threats are among the world’s 40 “least peaceful countries”. They include Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, Chad, India and Pakistan.

The descriptor “least peaceful” hides the terrible truth about how they got this way. Afghanistan and Iraq, which once enjoyed higher standards of living, have been plunged into war because of imperialist invasions and the never-ending occupations that followed.

These “least peaceful countries”, it should be noted, contribute little to global greenhouse gas pollution, as a World Bank graph for Afghanistan shows.

The report was produced to show which countries are least likely to cope with extreme ecological shocks. Thunberg has highlighted it just before European Union leaders meet to decide on a new climate law.

They are wrangling over an emissions target for 2030, with some pushing for the EU to cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 60% below 1990 levels by 2030. The EU’s current target is 40%.

The European Parliament will vote on the new law, including the target, next month.

Thunberg tweeted on September 10 that she and other climate activists had an online meeting with the chair of the environment committee of the EU Parliament. “We’ll tell him to vote in line with the Paris Agreement and the current best available science,” she said, receiving 4000 likes.

Like so many others, she knows full well that we are not all in the climate emergency together–not by a long shot, as the ETR makes clear. More than 1 billion people live in 31 countries where the country is “unlikely to sufficiently withstand the impact of ecological events by 2050”, it said.

This will lead to mass population displacement–climate refugees.

Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, the Middle East and North Africa face the largest number of ecological threats. Many are also in a state of permanent or semi-permanent war.

By 2040, 5.4 billion people–more than half of the world’s projected population–will live in the 59 countries experiencing high or extreme water stress, including India and China.

By 2050, 3.5 billion people could suffer from food insecurity, an increase of 1.5 billion people from today.

Those countries already identified as being most at risk of not being able to cope in catastrophic climate conditions are already finding it difficult to meet people’s basic needs. Climate change will lead to more conflict–over food security and basic resources. It will lead to mass displacement, putting greater strain on neighbouring poor countries.

These are more compelling reasons for why rich countries–those with the highest greenhouse gas emissions–need to act on the climate emergency. The effects of catastrophic global warming will be felt everywhere, but their deadliest impact will be on those countries that have contributed the least to this existential problem.

(MR Online is a web magazine started by Monthly Review, a socialist magazine published from New York. It seeks to be a forum for collaboration and communication between radical activists, writers, and scholars around the world.)

❈ ❈ ❈

Oxfam Study Shows World’s Richest 1% Emit More Than Twice as Much CO2 as Poorest 50%

The wealthiest 1% of the world’s population is responsible for emitting more than twice as much carbon dioxide as the poorest 50% of humanity, according to new research published Monday by Oxfam International.

The study (pdf), which was conducted in partnership with the Stockholm Environmental Institute, analyzed data collected in the years 1990 to 2015, a period during which emissions doubled worldwide. It found that the world’s richest 63 million people were responsible for 15% of global CO2 emissions, while the poorest half of the world’s people emitted just 7%.

The researchers reported that air and automobile travel were two of the main emission sources among the world’s wealthiest people. The study revealed that during the 15-year period, the richest 10% blew out one-third of the world’s remaining “carbon budget”—the amount of carbon dioxide that can be added to the atmosphere without causing global temperatures to rise above 1.5°C—as set under the Paris Agreement. It also found that annual emissions grew by 60% between 1990 and 2015, with the richest 5% responsible for 37% of this growth.

According to the study, “the per capita footprint of the richest 10% is more than 10 times the 1.5°C-consistent target for 2030, and more than 30 times higher than the poorest 50%.”

The researchers noted a sharp drop in CO2 emissions during the coronavirus pandemic. However, they said that “emissions are likely to rapidly rebound as governments ease Covid-related lockdowns.”

In 2020, climate change has fueled deadly cyclones in India and Bangladesh, massive locust swarms that have devastated crops throughout Africa, and intense heatwaves and wildfires in Australia and western North America, among many other events.

Oxfam is calling for more taxes on high-carbon luxuries, including a frequent-flier tax, in order to invest in lower-emission alternatives and improve the lives of the world’s poorest people, who are the least responsible for—but most affected by—the disasters and harm unleashed by global CO2 emissions.

“The over-consumption of a wealthy minority is fueling the climate crisis, yet it is poor communities and young people who are paying the price,” wrote study author Tim Gore, Oxfam’s head of climate policy. “Such extreme carbon inequality is a direct consequence of our governments decades-long pursuit of grossly unequal and carbon intensive economic growth.”

(Brett Wilkins is staff writer for Common Dreams. Article courtesy: Common Dreams, a US non-profit newsportal.)