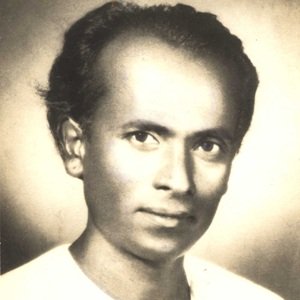

Milind Awad

Annabhau Sathe, whose 100th birth anniversary falls on August 1, wrote 35 novels, 13 collections of short stories and a few plays grounded in realism. He also wrote street plays, a travelogue and songs and lavanis (a dance form that has contributed significantly to Marathi folk theatre), which created a storm in Maharashtra.

The songs were written during the movement for a unified Maharashtra in the late 1950s. The Sanyukta Maharashtracha Chalwal (Unified Maharashtra Movement) was led by the Marathi working class as well as the caste and political elite. Two different strands of leadership arose. The communist leader comrade Dange, S.M. Joshi, Achrya P.K. Atre – who promoted the movement in urban areas, especially Bombay – were from the dominant castes and Annabhau Sathe, Amar Saikh, Gavankar and Nana Patil, who campaigned in rural areas, were from non-Brahamanical castes. This division has received hardly any intellectual attention even though it formed a crucial moment in Annabhau’s life, as is evident from the povadas (eulogies) he wrote like Maharashtrachi Parmpara (Tradition of Maharashtra).

In the Mumbai of 1940s and 50s, Annabhau Sathe struggled along with the mill workers and industrial workers. He travelled widely in rural Maharashtra and raised support for the demands of agricultural labourers and peasants, both as a poet and as an activist with Lal Bhawta Kalapathak (Red Flag Cultural Troop). Annabhau’s intellectual work contributed to and drew inspiration from anti-caste, anti-class ideology and movements in contemporary Maharashtra, which was forcefully expressed by his povada, “Jag badal galun ghauv, Sanguna gele maje Bhimarao” (Change the world with a hammer stroke, Bhimrao said to me).

Annabhau started writing in the middle of the 20th century, at a time when novels, short stories and plays were being written mainly by the caste elite, the inheritors of the Indian Renaissance. Although he did not possess the literary surplus that stemmed from this cultural capital, Annabhau was a prolific writer. However, his lack of cultural capital also led to the relative lack of appreciation and recognition—there was no critical discussion around his work and his work was never translated into English. His work was distinct from what was being written by the contemporary Marathi middle class. If one tries to distil the ideology underlining his work, it is one of action and constantly moving resistance which comes from his own interactions with his social reality.

His writing was sporadic; he never organised or dated his work. It can be argued that one of the reasons for this is that most of his work was politically charged, circumstantial, contemporary and issue-based. Annabhau himself did not live in the circumstances that would enable him to organise and maintain his work chronologically. It is also possible that he saw his work as his productive contribution and once performed or published, he did not assert his claim over it as “his” intellectual property.

He writes in his inaugural speech of the first Dalit Sahitya Samelan, in 1958:

“The cracked vessel on a three-stone makeshift fire placed under a tree and the Dalit that cooks for his two children and wife may appear pathetic. But this Dalit’s will to survive is rich, phenomenal, heroic. His faith and relation to his family structure is undiminished, unshaken. Capitalism has shoved his family under this tree. Observe this search for its causes.

“The need of the hour is to understand why this Dalit appears pathetic. And to cautiously render this in writing because every move society makes is linked and powered by the Dalit. This earth is not balanced precariously on the Shesh Nag’s hood, but rests secure in the Dalit’s and worker’s hands. This Dalit’s life is like the birth of a fresh spring from a mountain’s rocky peaks. Go close, look, and then write.

“For Tukaram’s truth still holds: to understand people you must live with them. Writing on Dalit’s must be committed to them. You are not slaves. This world is in your Hands. Let them know this. Strive to improve their lives. To do this the author must live with his people. The artist that lives with the people is the artist the people stand by. The author who turns his back on people will find that literature has turned her back on him.

“As every artist knows, art is like the third eye that pierces the world and incinerates all myths. This eye must always be alert and must always see for the people.”

Creating a binary

Annabhau’s writing deals with the pathos of an untouchable’s life, circumstances and conditions. His body of writing covers a wide range of characters, social conditions, and eras. He creates the binary between urban and rural, pre-independence and post-independence, workers and the poor, untouchable and touchable, man and woman, etc. As a writer, he described the alienation of the socially excluded beings; the conditions of this alienation are dealt with in-depth but with narration. His writings provide the reader with an opportunity to enter into the paradigm of untouchability, slave-labour and enforced poverty.

In the introduction to a Marathi short story ‘Barbadya Kanjari’, Annabahu writes that:

“The life I live, see and experience is the life I write about. No bird am I to fly on the wings of fantasy. I am a frog, close to the ground…When Barbariya’s ear was cut off, I was sitting in the dark and watching… Sultan, Bhomkiya, and I were in Amravathi jail all facing murder charges… Mukul Mulani still calls me mama (uncle)… The Tuka who ate the donkey out of anger is still alive… All my characters are real, alive.”

As a Dalit writer and proletarian thinker, Annabhau Sathe is one of the leading writers of Maharashtra. His writing is an example of the innate fusion of anti-class and anti-caste ideas. In the 1960s, his writing gave sophisticated creativity to the Dalit cultural and social movement, particularly in Maharashtra. Annabhau’s writing configures the value of self-pride, dignity and militancy to the movement. Annabhau Sathe’s literary activity gave Dalits a consciousness that proved to be a decisive factor in framing the contemporary Dalit political, social and cultural movement in Maharashtra. His writings are useful and unique tools to understand the untouchable community’s everyday life and world. Due to these and other charismatic reasons, he is a central figure of the Dalit literary movement in Maharashtra.

(Milind Awad teaches at Centre for English Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. His work involves pedagogical engagement with caste studies and contemporary Dalit Writings. All translations by the author.)